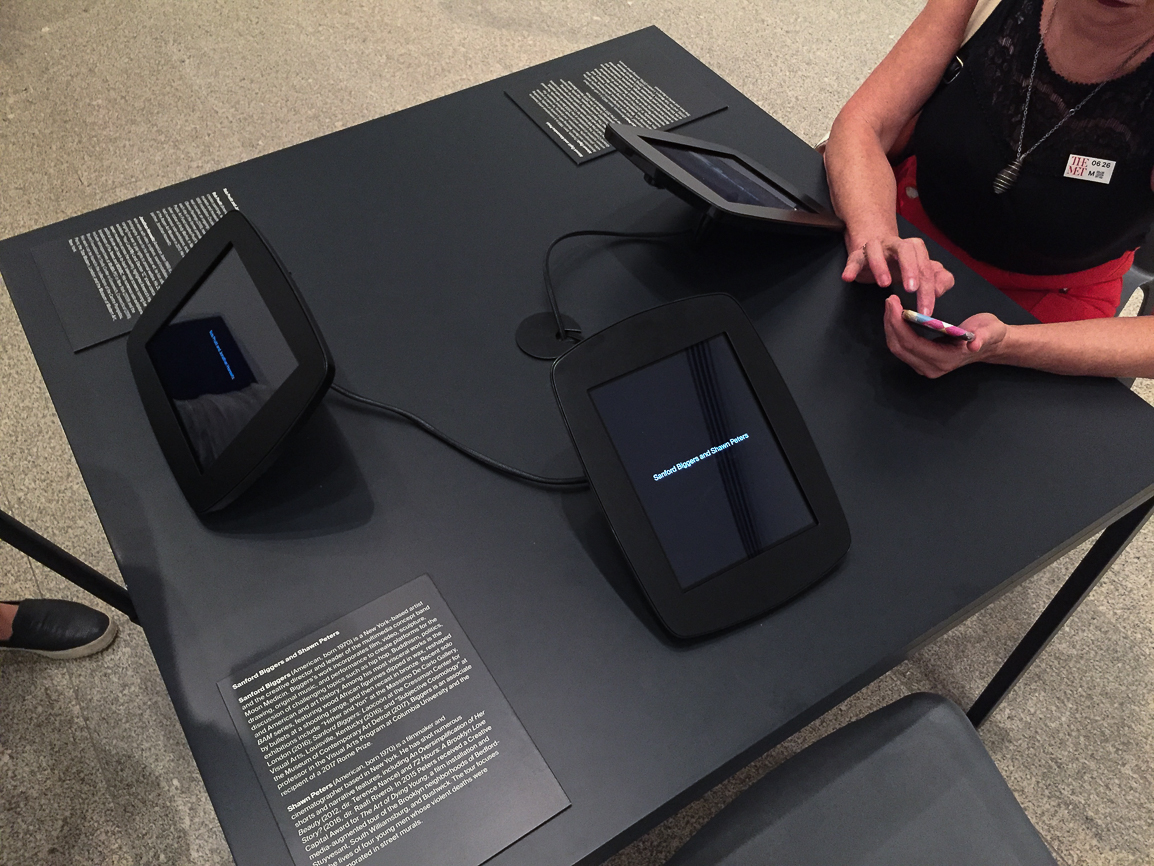

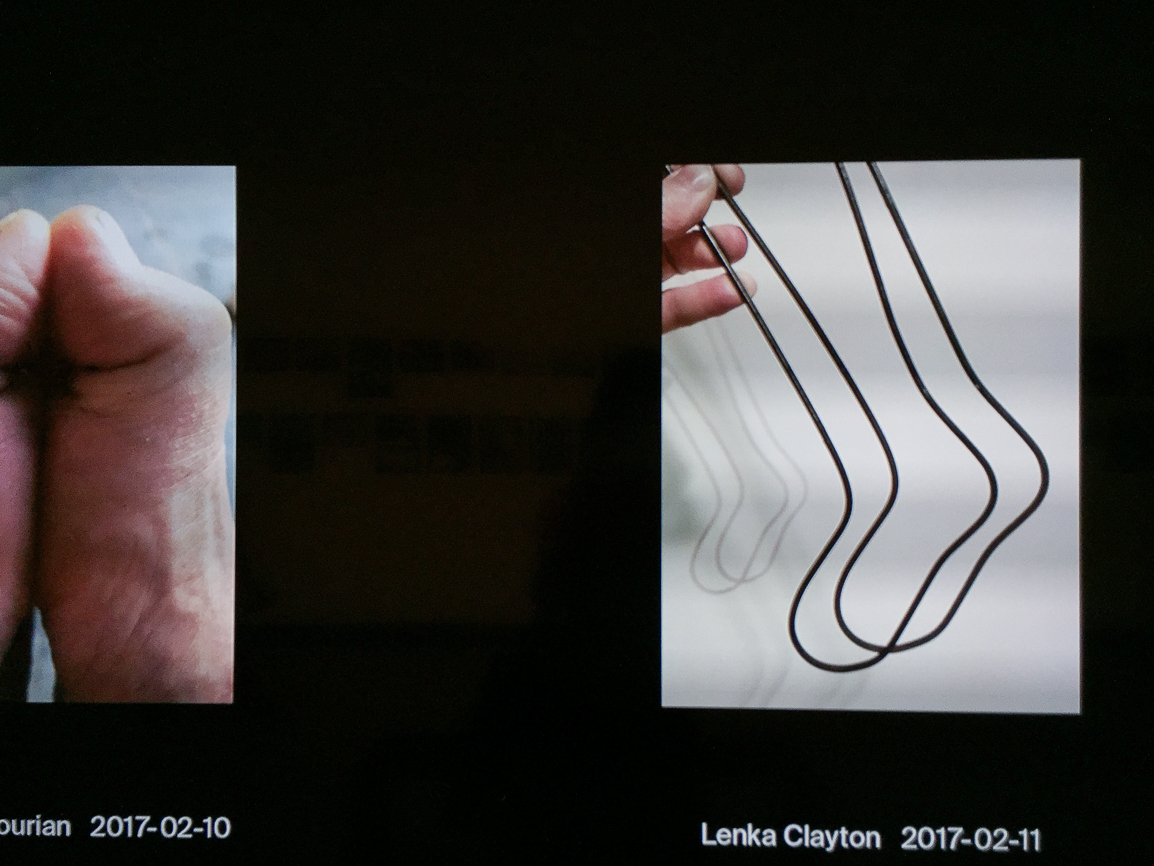

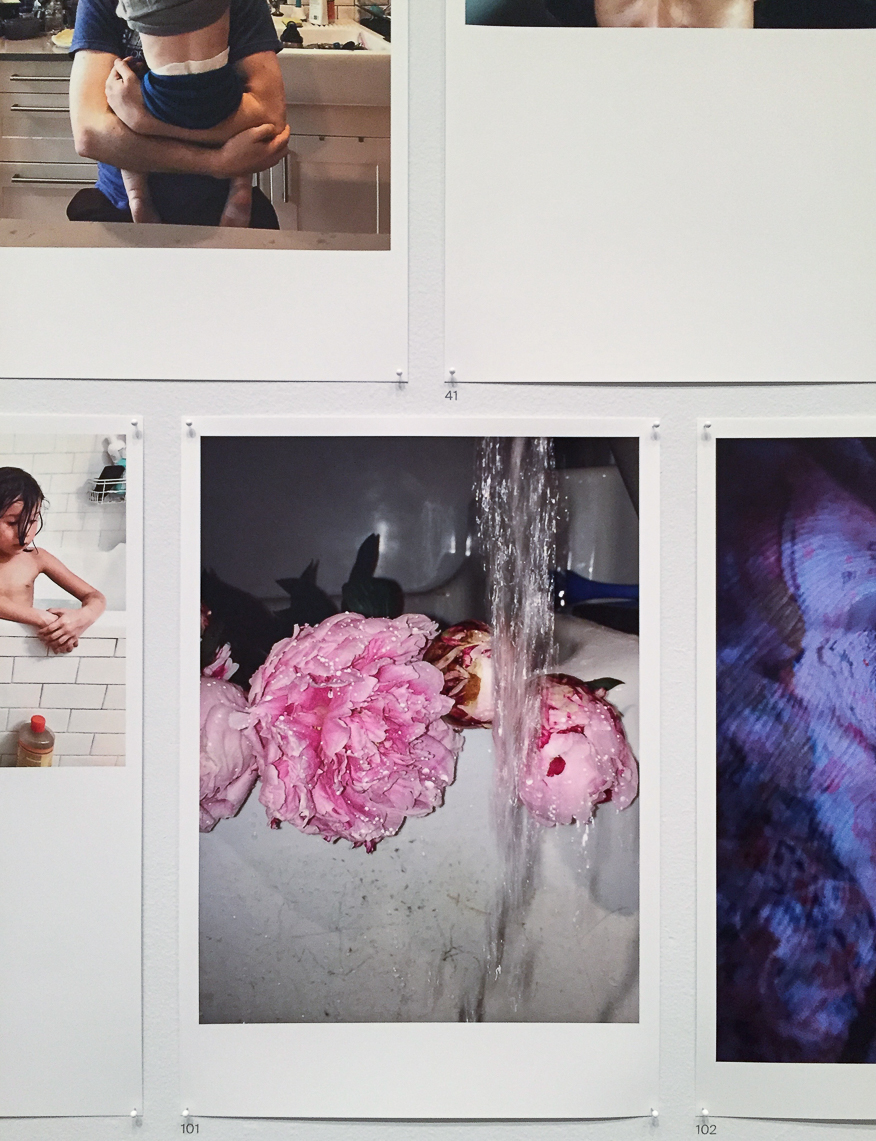

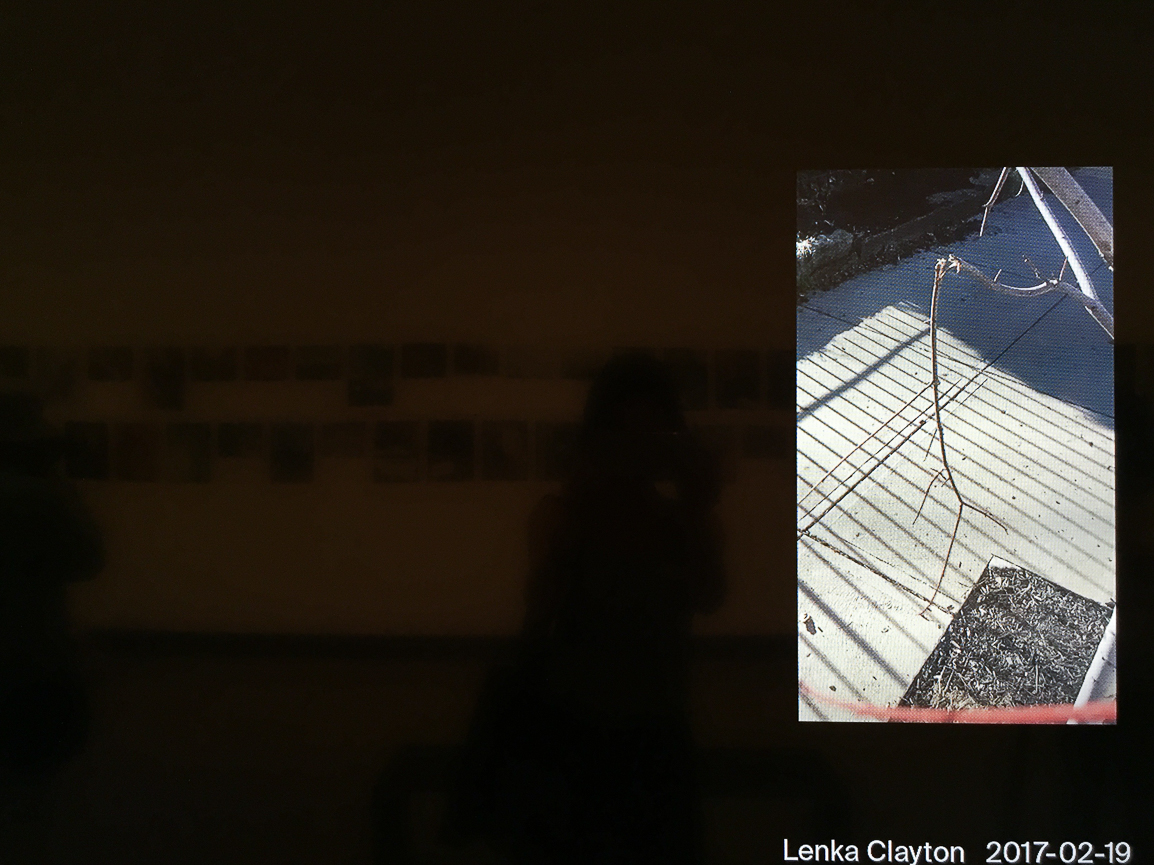

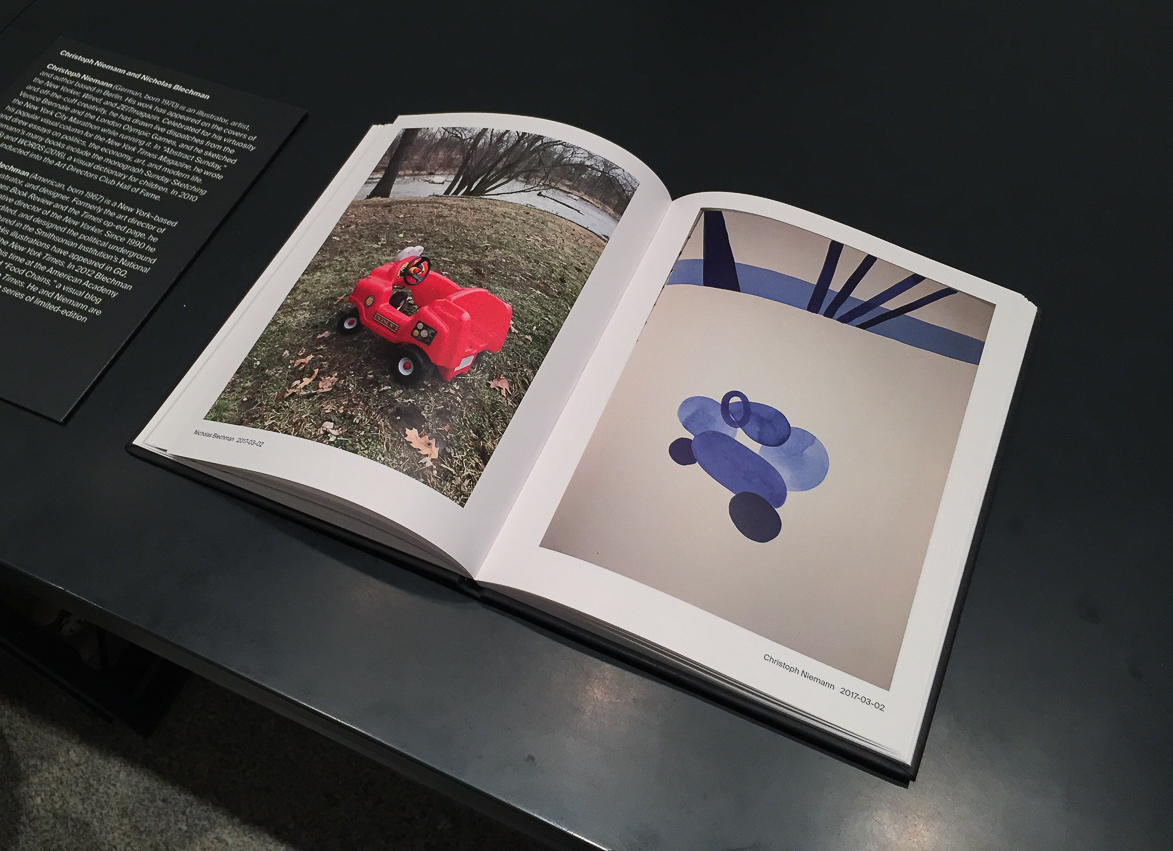

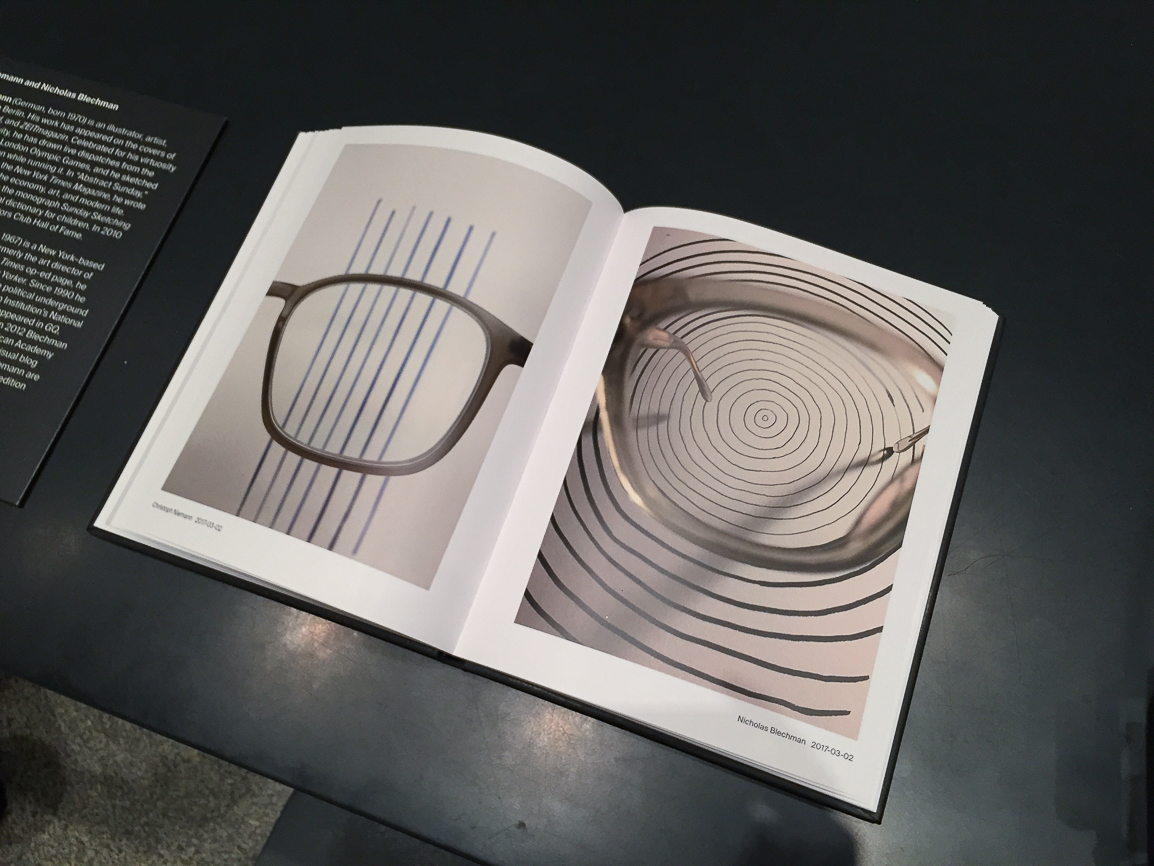

Fine Art Through the iPhone

'Talking Pictures: Camera-Phone Conversations Between Artists' will be open through December 17th, 2017.

Stay informed on our latest news!

'Talking Pictures: Camera-Phone Conversations Between Artists' will be open through December 17th, 2017.

This one-of-a-kind vehicle integrates color-change technology with the signature colors and geometric patterns we’ve come to associate with Esther Mahlangu's work. To ensure the faithful recreation of every intricate detail of the ornate artwork, the BMW i5 Flow NOSTOKANA has been fitted with 1,349 individually controllable sections of film.

The complex colors and patterns showcased in the artwork offer a glimpse into the future potential for customized vehicles that fans of BMW’s innovation can look forward to. We took time from exploring the artwork to catch up with Stella Clarke, BMW’s research engineer as well as Esther Mahlangu in order to understand both of their perspectives.

What about Esther makes her the right artist for BMW to collaborate with?

Stella Clarke, Research Engineer Open Innovations, BMW Group - I think there's a number of things there. So, the journey to this car started about six years ago and before we even had prototypes, I had a pitch deck to try and convince people of using E Ink in a car. And at the very end of that pitch deck came a picture of her looking at her art on the dashboard with a huge smile on her face. And that was the moment where people understood what I wanted to do with E Ink. So that was really a key moment and a key inspiration for everything that happened after that.

Second of all, it just fits in really well together, her art with the idea of color change in multiple ways. Of course the art is very colorful and the ability to kind of change the color brings a dynamic element, a modernity into her art. Throughout the history of this African art from the Ndebele culture, there's also a certain progression in there. They started painting with earth colors, just colors of the materials that you had around. And then when acrylic colors came, they moved onto that and she was the first person to take this art and put it onto canvas. So innovation has always been a part of her and her art as well. And so this is a way to continue the story of innovation with her art on our car. And she did paint the 12th art car BMW art car, which is quite legendary. And so this was also a nice way for us to pay homage to her art car while also showcasing the innovative side of BMW.

How do you think her style and vision compliments BMW's design philosophy?

Stella Clarke - I think the playfulness of her art, and the joy in her art fits together with the joy of what BMW tries to bring to its customers and the products that we make.If you try to ask Esther philosophical questions about her art, she says she just wants to bring joy to people and she wants to kind of show her tradition to the world. And I think it's the same thing that BMW wants to try and do, bring joy. It's a part of our slogan, right? Bring joy to the customer. And also a certain amount of heritage is also in there with BMW, that we are also proud of.

Why do you feel it's important for BMW to merge the worlds of art and automotive design?

Stella Clarke - I think BMW has always supported the arts and here we're seeing a kind of fusion of art and innovation. And I think those two go hand in hand. I think something that's innovative and something that is creative is something that brings joy, brings light, perhaps even a certain amount of disbelief. And we've done this with our changing colors so far. We know that people often can't believe what they're looking at. And I think art often aims to do that as well, right? The art kind of aims to push your mind. It aims to delight, it aims to bring you joy as well. And I think that's how art and innovation can come together. So I think we can both learn from each other because we both have the goal of delighting and bringing joy to people.

Do you think art, and this collaboration in particular, will shift perceptions of traditional car design?

Stella Clarke - I think so. I think it's a wonderful playfulness that we're showing here. And I think not only this car, but the other cars that we've done with color change so far with E Ink. There, we showed cars that can change their colors and we know based on the reaction that people like to express themselves with their car. So this really brings a new element into car design. It means that you, yourself, every owner of their car can become their own designer. And at any given day, you can choose how you want to express yourself with your car. It's a new dimension in terms of car design.

What about BMW as a brand makes them the right fit for a collaboration?

Esther Mahlangu - I have a long and mutually beneficial relationship with BMW that goes back to 1991. They have proven their interest and commitment to art over many decades through the BMW Art Car Collection, sponsorship of art fairs, work with museums, and now my Retrospective Exhibition and the tour thereof.

What considerations have to be made when collaborating with such a big company like BMW?

Esther Mahlangu - BMW has been very easy to work with. I have not had to consider many things in our collaborations. They have proposed different projects to me which I have agreed to do and they have been very successful. My gallerist proposed my Retrospective Exhibition to them, and they agreed to support it for which I am grateful.

Were there any creative limitations?

Esther Mahlangu - There have not been any creative limitations other than the medium itself. They have provided me with a car, and I have looked at it as a medium on which to paint or apply my designs.

What elements of the artwork do you feel speak most to your South African heritage?

Esther Mahlangu - I was taught the art of Ndebele design as a young girl as is tradition amongst my people. Everything about what I create is therefore closely associated to South Africa, something of which I am very proud.

Has there been a shift in the creative process since the first BMW collaboration in 1991?

Esther Mahlangu - My last two projects with BMW have been very different from our first collaboration in 1991 as they did not require me to paint onto the vehicle. Both used the latest technology to apply my designs to the cars.

Was it difficult to adapt to and welcome technology into the fold?

Esther Mahlangu - It was a simple process to include my designs whilst I expect that it was more difficult to come up with the technology that allowed for this.

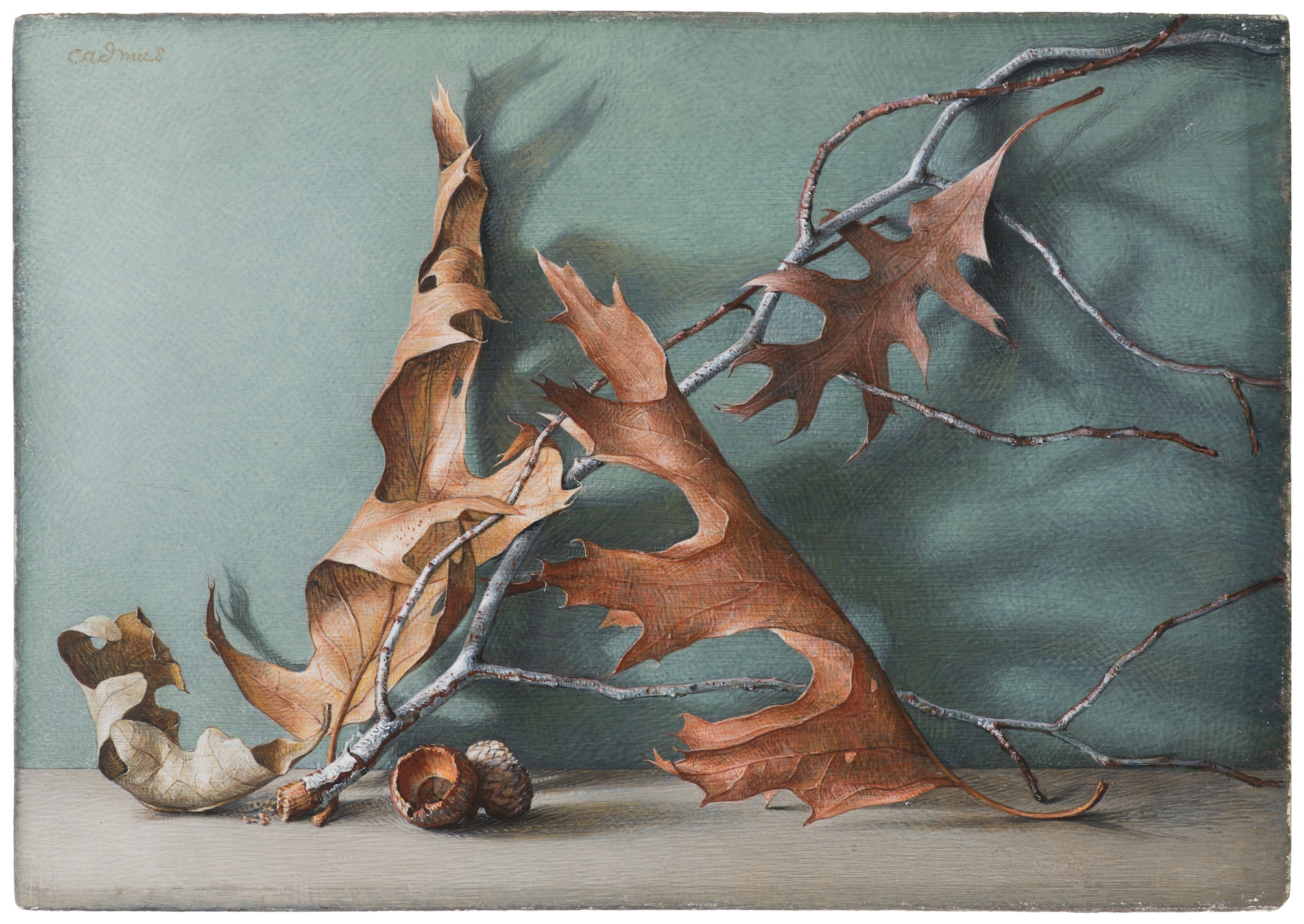

The world, at least in 1937, seems to have agreed on the powers of the lamb. That year, the artist Paul Cadmus opened his first solo show at Midtown Gallery in New York boasting artworks of male physiques and satires of American nightlife. Everything from his show sold out. It drew a record-breaking audience of seven thousand homosocially curious lions, lured in by an artist compelled to depict men as if they were potent lambs as evinced in his painting, Y.M.C.A. Locker Room, 1933. It was all very gay. For this, the artist garnered mainstream attention and inclusion in art history. Life magazine fueled America's intrigue, emphasizing Cadmus’ cheeky fascination for depicting, “the play of muscles and the stretch of skin above them.” (Incidentally, Cadmus’ men appear with little if any visible signs of body hair, resembling sheared lambs free of wool coats, perhaps something de Beauvoir would have found less repulsive).

A few years later, the 1941 Encyclopedia Britannica entry for ‘Famous Paintings by Modern American Artists’ linked Cadmus with Regionalists Grant Wood and John Steuart Curry and soft psycho-realist Edward Hopper. This moment of late American modernism would not last. Like all movements in art history, they, too, were succeeded by another scene. Cadmus was met with fierce condemnation and brutal acts of censorship for his boisterous tableaus of cross-class contact rich with sexual innuendos while his less gay peers were succeeded by the Abstract Expressionists. The Ab Ex painters were sponsored by clandestine CIA “donations,” and written with great esteem by academic art critics weaponizing their institutional powers of intellectual prestige to refashion history, whether that of art or sexuality, to their own liking.

History loves persecuting sexual minorities. There is no exception to this, not even from the ancient Greeks who were rather generous with their sculptures of naked mortals, demi-gods, nymphs, and goddesses. In response to an email I wrote to A.B. Huber, one of my undergraduate thesis advisors, Huber shared this anecdote, “I kept thinking about the fact that when the first stele of hermaphroditic figures were being made in Greece, actual intersex babies were ‘put out to sea,’ that is exposed and drowned as monstrosities that threatened the community. Sometimes non-normative bodies are celebrated in art or ritual objects but loathed in reality.” Why is the reality of everyday life often overlooked, censored in art history?

Whatever, for Cadmus and Cadmus’ friends, life was always a beach. In February of 2024, D.C. Moore gallery showed the artist’s first major show in over 20 years, Paul Cadmus: The Male Nude. It relied heavily on works of beauties traversing Fire Island’s sandy shoreline, beachside mansions, and White Oak and Red Swamp maple-covered loveshacks (Camp Cheerful, 1939; Pine Cone and Bark, 1955; and, Winter Still Life, 1970). They circulate across the gallery’s scarlet-colored walls. There are several still lives and dozens of nude figures drawn with fast, fluid marks or painted with egg tempera and highlighted with crayon. His figures have flesh that bulges or twists similar to artists like Tom of Finland or Jiraiya. However, what distinguishes Cadmus from these guys is that his figures appear to glow to the point of otherworldly enchantment.

Some figures read and eat apples at the beach like in Two Boys on a Beach, c. 1936. Nearby a boy yawns. Others lounge at ease and yet appear to be stretching. It’s uncanny.

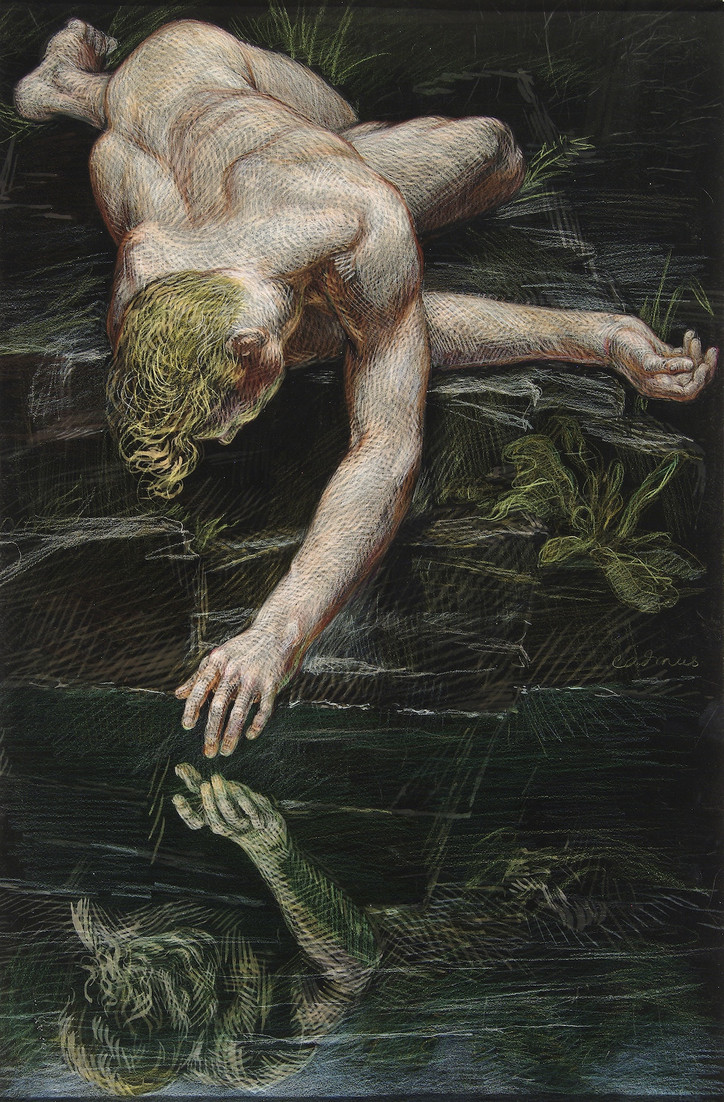

Narcissus: Study for an Homage to Caravaggio, 1963, 1983

Tempera and ink on board, ca. 1963; crayon added in 1983

Collection of The Tobin Theatre Arts Fund, 75.2007.

Courtesy of the McNay Art Museum, San Antonio,Texas.

A luminescent boy in one tempera, ink, and crayon drawing, Narcissus: Study for an Homage to Caravaggio, 1963, 1983, lays sprawled out on a bed of Fire Island’s feathery grasses, like soft rush and switchgrass. His gnarly, lean flesh folds around himself as if frozen mid-motion while tumbling downhill. His firm ass protrudes at the center of the drawing. He arches his back. It creates a nice shadow-line that runs through the length of his spine. His neck, head, and blonde and white curls all meet at the end line. His head along with an outstretched left arm fall off a bayside barrier. They hover above murky saltwater located at the bottom of the drawing. His head peers downward into the water while his fingers reach out to his reflection. In this intricate tableau, the boy becomes a focal point, not merely a subject but a representation of desire itself. His naked form, frozen yet seemingly in motion, with an outstretched arm drawn in a phallic manner, invites his reflection as well as the viewer into the scene. His outstretched arm inches closer to the picture plane, coming towards the viewer. The viewer stands outside the picture, wading nearby in the salt water just beyond the boy’s reflection. Here, the artist blurs the boundaries between observer and observed, lover and beloved.

Cadmus was a huge fan of triangulations. The triangulation inherent in this composition echoes the complexities of attraction, where the paradoxical interplay of both the law of desire and the rule of seduction unfold. Something to mention, especially, about desire and seduction: desire follows the law of gratification whereas seduction follows the rule of intensification. For the desiring subject who breaks the law of desire, they are punished. But like most lawbreakers, they’re given another chance to play again once penance has been paid. Seduction does not let you play again. It follows the rule — not the law — of intensification. Once the seducer breaks the rule of intensification (becoming avoidant, anxious, or secure to the point of barrier breaking intimacy i.e. empathy) they must exit the scene. The game of attraction ends.

Between the boy, his reflection, and the viewer positioned just outside the frame, a delicate dance assembles. The boy's gaze fixates upon his own image. It’s a gratifying manifestation of his beauty. But granting that gratification threatens to extinguish desire itself. In most versions of the story of Narcissus, the boy dies once he falls into his reflection. If this drawn boy falls into the water, he would be breaking the rule of seduction — not desire — by choosing to end his life. Instead, he intensifies seduction by continuing his gaze as he reaches out to the viewer. His beckoning gesture asks the viewer to participate in this erotic scene. We, the viewer, are gratified by him including us in the scene. His hand calls for the viewer to make a decision: to grab his hand and roll along with him on solid ground or to pull him underwater. Here is both desire and seduction continuously at play. The boy's control over the scene is tenuous, contingent upon the triangulating motion of desire and seduction. The story only continues, though, if the viewer grabs his hand and joins his decelerating tumble.

The Shower, 1943

Egg tempera on pressed wood panel

15 1/4x15 1/2inches

Private Collection

Elsewhere in the show, there's a painting showing a hunk covered in droplets and soapy suds. He is enjoying an outdoor shower (The Shower, 1943). A woman wrapped in a bed cloth watches as a wildfire summer sun burns behind her. Below the hunk is a skinny man who reclines, patiently waiting to be summoned by either of these two lovers. Again, triangulations were no stranger to Cadmus’ artistry and life. The artist took part in a collective with Jared French, Margaret French, and himself, colloquially called PAJAMA as shown in the photograph on display, Paul Cadmus and Jared French, Fire Island, 1941. The throuple lasted for a significant portion of his life. This was brought up several times during a packed-house conversation on the legacy of Paul Cadmus and Fire Island this winter. The conversation was shared between art critic Justin Spring, BOFFO co-founder Faris Saad Al-Shathir, and photographer Matthew Leifheit. But, the artist was more than his triangulations. He collaborated with a cohort of mostly white creatives like the photographer George Platt Lynes, Lynes’ on again off again lover, the MoMa curator Monroe Wheeler, and the painter George Tooker. In reality, these were his companions. This was the art historical movement in which he found pleasure and safety to be himself. He helped build it and so he belonged to it.

One of the artist’s favorite scenes was wherever water meets land. More often than not his scene was the beach. In the most literal sense of the word, a scene is a moment of “intense affection,” similar to scenes found in a book or a movie. They also appear in drawings and paintings. Social scenes, too, are moments of “intense affection” where both pleasure and safety are interconnected at a much larger scale. What feels special about Cadmus was his knowingness that much of his scene wouldn't last. He navigated his faggy way of life, the polyamory, the earnest pursuit of some idealized human form, the thumbnails of bullish men, sailors, twinks, trade, glammed out dolls, gangsters, hookers, beefs, queens, faeries, all entangled and enthralled with one another.

The Fleet’s In!, 1934

Etching

7 1/4 x 14 1/8 inches

D.C. Moore’s founder Bridget Moore added to the conversation noting that the government did not value a lot of the artwork created for the United States Public Works of Art Project (WPA) after the war and, unbelievably, sold many paintings for linen scrap for pipe fittings. These works, along with artworks by Cadmus' peers were sold at garage sales or thrift stores. Further to the point of trash, it’s no surprise that one of Cadmus' paintings made while a member of the federal government funded WPA was removed from public view. Perhaps it was because he was outing all sorts of men in the military. “In 1934, one of Cadmus’ very gay paintings, The Fleet's In!, 1934 (it would later inspire a major motion picture), was quickly removed from public display. It was stolen by a retired navy admiral who, contradictorily, installed it at a men's-only Alibi Club in Washington, D.C. It lived there for four decades. A year before Cadmus' The Fleet's In! was removed, Diego Riviera had his mural burnt off the wall of Rockefeller Center because he wouldn’t remove his portrait of Lenin from the center of it. All the best artists were queer communists,” shared an audience member during the conversation’s Q & A. By outing the whole military, did Cadmus fuel military turmoil?

Spring confidently responded. He seemed to think this was most likely not the case. He noted that figuration in art history has always been queer and that Cadmus’ practice of queer realism by means of figuration was not all that political. The critic seemed to be missing what the audience member was suggesting. Said audience member responded, “I suppose I agree with you that figuration has always been queer (because people are),” echoing Huber. “However, America did put Cadmus’ style of figuration entirely back into the closet to avoid the issue of America’s very public queerness. America wasn't ready for queer figuration, but Cadmus was insisting on it 90 years ago!” furthering Huber’s illustrative example. The packed gallery stirred at the lamb's captivating come-on. A faint smile materialized on the critic's face, begrudgingly acknowledging the lamb's charm.

There’s more to share. Continuing de Beauvoir’s observation, she notes that, "If the prehensile, possessive tendency exists more strongly in women, her orientation... will be toward homosexuality." Here, de Beauvoir is not wrong. Homosexuals, those women attracted to women or men attracted to men, have an intimate understanding of attraction’s complexities and know best how to navigate, if not totally transfigure, scenes of intense affection and desire. They tend to extend beyond the conventional roles of lion and lamb, lover and beloved. At times, the lamb turns out to be a wolf in grown up lamb’s clothing.

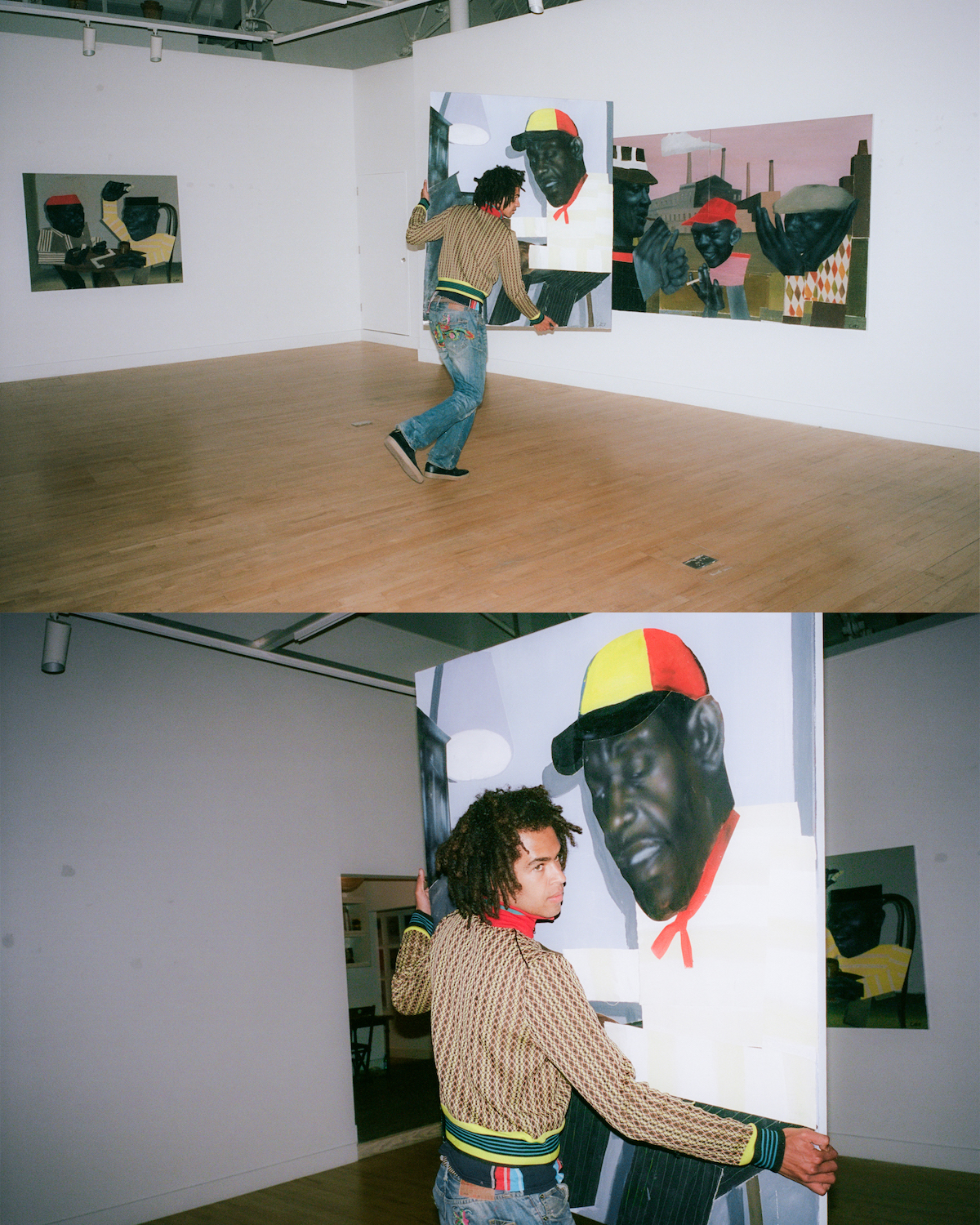

Tell me about your current show SEEN! that is opening imminently.

The [Cooke Latham] gallery were the first people to offer me a solo show, so that was really exciting. The LA show happened quicker… but for this it was the first time I was in my studio in London, working on paintings that would have to work together on four walls, and that was really fun.

What was your methodology behind this show?

What I wanted to do was introduce taking my own photographs and finding real characters, Caribbean people in Peckham and Brixton, to photograph. So I asked these casting agents to find older people to come round the studio to take portraits of, which I took with my sister Maya and her boyfriend Dominic (who work under MISSOHIO as a photography duo). I started by collecting photos of people with really cool expressions and next was my research of African photographers to find the right characters that spark my imagination. Then I paint those faces first on stretched canvas and start pairing things together. I paint with acrylic and airbrush until they start talking to each other within the painting and then I build their bodies and stuff around that.

One of the guys who came, who's called Tony Culture, had a sick outfit so that just made it easy because I could use his whole vibe for one of the paintings, which is the one I posted first. So I just try to make little moments, little scenes with those characters.

And I know your work also hinges on art histories to an extent too…

I’m influenced by photographers like Malick Sidibé, and different painters who would try and make sort cultural underground scenes into the subject matter of the paintings like Manet and Picasso. And then I always go back to Romare Bearden for the specific way he composes bodies, and I managed to find some really good books of his in America which helped inform what I was doing.

My earlier work would start with musicians as the subject matter, but I’ve wanted to move a little bit away from that, and developed it into any moment of life between people. So there's guys playing dominoes, and people chilling outside the factory where they work.

Are you pulling from both fiction and real life in these scenes you're creating?

Yeah, I want it to look relatable to real life, and I like realistic storytelling in films and stuff where there's the local characters that might crop up in a film. Also my Dad’s writing is quite like that where the older people he grew up around are fictionalised into something entertaining but quite nuanced real life stories.

It feels like your paintings are… auto-fictional, perhaps? And anecdote is such a great material, for both writing and art.

I love books that pull together from little stories rather than a grand narrative and I love that in films as well. I grew up with a lot of stuff like that.

I was also wondering if travelling is influencing your practice at all?

Yeah, I think in LA it was more so ‘space and time’, I wanted it to be more culturally significant than it necessarily was but definitely being in Mexico there was a massive choice of culture. I like to be a little sponge when I pull up somewhere, and get the low down of a new spot.

A lot of places I go to I've already got some idea about from films. Like Jamaica is my whole upbringing, me and my sisters were always thinking about Jamaica and we had our ideas about it. But actually going there was amazing because of the story telling from cab drivers, and a waitress we met around the first place we stayed would go really deep into a story about her family unprovoked… but I love picking things up along the way whenever I’m travelling.

I feel like you’ve got a really rich set of references that you’re pulling from, loads of different disciplines and then your paintings speak in these different tones, colour and texture, and scale feels really important, they look massive. And then I think they almost feel like your animations in that way, they feel super alive.

I think my favourite form of art is film so I wanted it to lend itself towards that medium because I haven't learnt about cameras yet. It’s a way to learn about those things through painting, and collage makes it easy because you can animate the characters by moving them round and they can settle into a still rather than a really composed idea. You can move them until they look really comfortable and dynamic. And I look at a lot of animators who would just use cut outs and still make them alive, even though the individual parts are quite rigid. I like the idea of bringing them to life after they’ve been painted.

It's got this old school sentimentality of being really manual and tangible, and I love the idea of you personally performing that camera function without having to use an actual camera.

Yeah exactly. And all the animation I love tends to be the really tactile stuff where you can see the mistakes or you can see the artist's hand in it. And the photography I like is usually quite low budget, one flash kind of thing.

It’s very humble. I think that's the kind of work I’m really enjoying at the moment, work that’s in one sense loud, but in another sense not arrogant.

Yeah, yeah I like that a lot. That's definitely the tone I like; it's not showing off too much and quite down to earth.

But it doesn't have to be because it's so exciting, it speaks for itself.

I think something I try to be conscious of in my life is that people in the street are fascinating. Even if they're not praised, all those people, I want to hear their stories. I want to interact with them and that's when I feel I’m in a good place, when I acknowledge the people in the high street who have been there longer than me.

I wonder if that has something to do with growing up with Black elders?

Definitely. That reminds me of my uncle and listening to him and my dad just chatting. My uncle will be going off on tangents…

There’s something about an older black man telling a story that's just everything!

My uncle is just outrageous. And then my mum will be the only person who will actually challenge it. They have really funny interactions.

Do you think your work wants to capture these kinds of dynamics then?

Yeah, definitely. I want it to be that kind of thing you hear from the elders. They want to give back to you, so giving credence to their story from the position of being young is very important to me.