Found In Translation

If this were a memoir, my first solo trip would have begun with a blind finger, a worn map, and a next day flight. But it’s not; and if I’m being honest, I simply chose a place that didn’t require a car.

I ended up racing a thunderstorm on the deepest lake in Central America, calculating the likelihood my obituary would be credited to the fifteen-year old captain whose name I couldn’t speak enough Kaqchikel to ask. Framed by three volcanoes and nearing its 85,000th birthday, Lake Atitlán has no roads connecting place to place. Each of its seven villages are accessible only by boat — and I didn’t drown once.

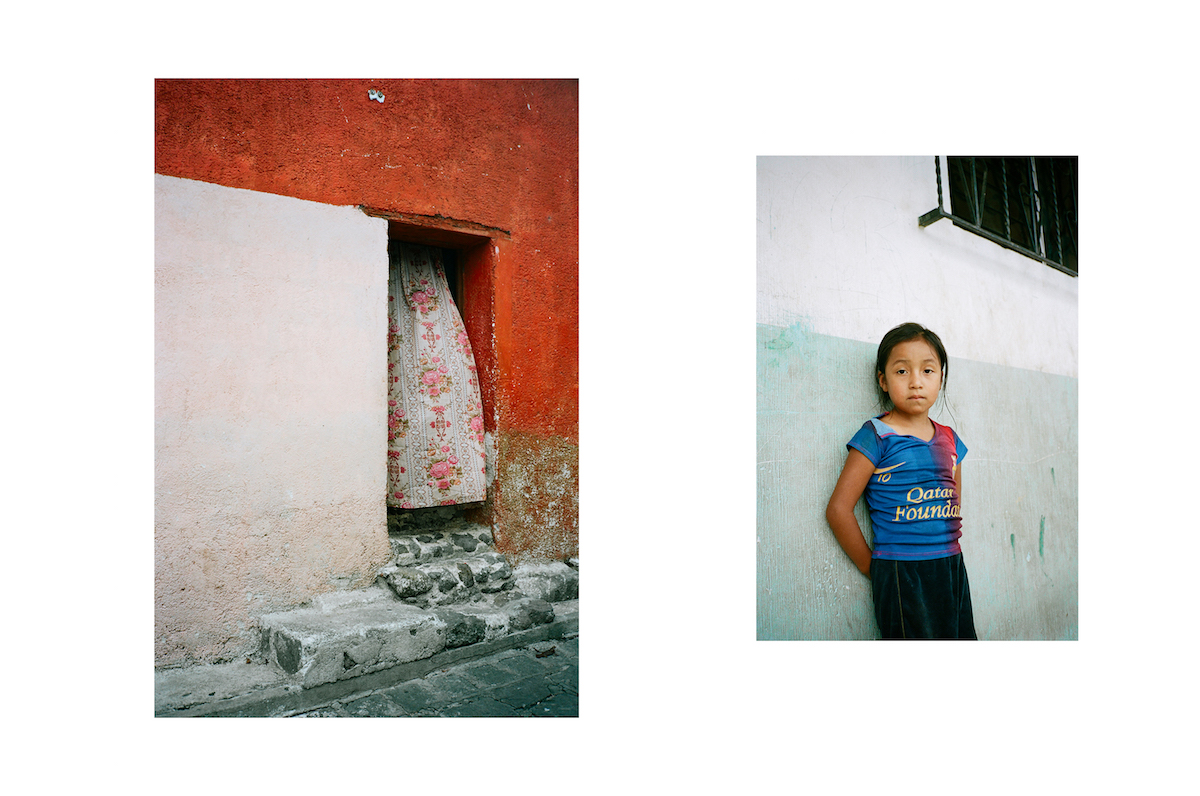

Common fascination with Atitlán stems from the lake’s mysteries — a 50-feet-below Mayan empire to archaeologists, a prana-altering energy vortex to mystics, an affordable dreamscape to tourists — but what captured me was the enigma of its land. A rudimentary history: Mayan peoples inhabited the region for millennia before the invasion of Spanish conquistadors, convergence with Catholic saints, overthrow of military-controlled genocide, and assimilation of Western (bad) habits.

Today, the Tz'utujil, the Kaqchikel, Guatemalans, and gringos, coexist in curious harmony— you can just as easily find effigies of Maximón as you can drink Coca Cola by the case. Yet what is traversed in contemporary custom is broken in dialect: twenty Mayan languages, ubiquitous Spanish, limited English. And with the absence of universal speech, came the question of communication. Armed with a pocket-sized translator, I approached the barrier with patience, humor, and a little luck. A brief exchange of names. Abstract outlines drawn in the air, written arrows on a map.

Mostly, we just laughed.