Free Lunch

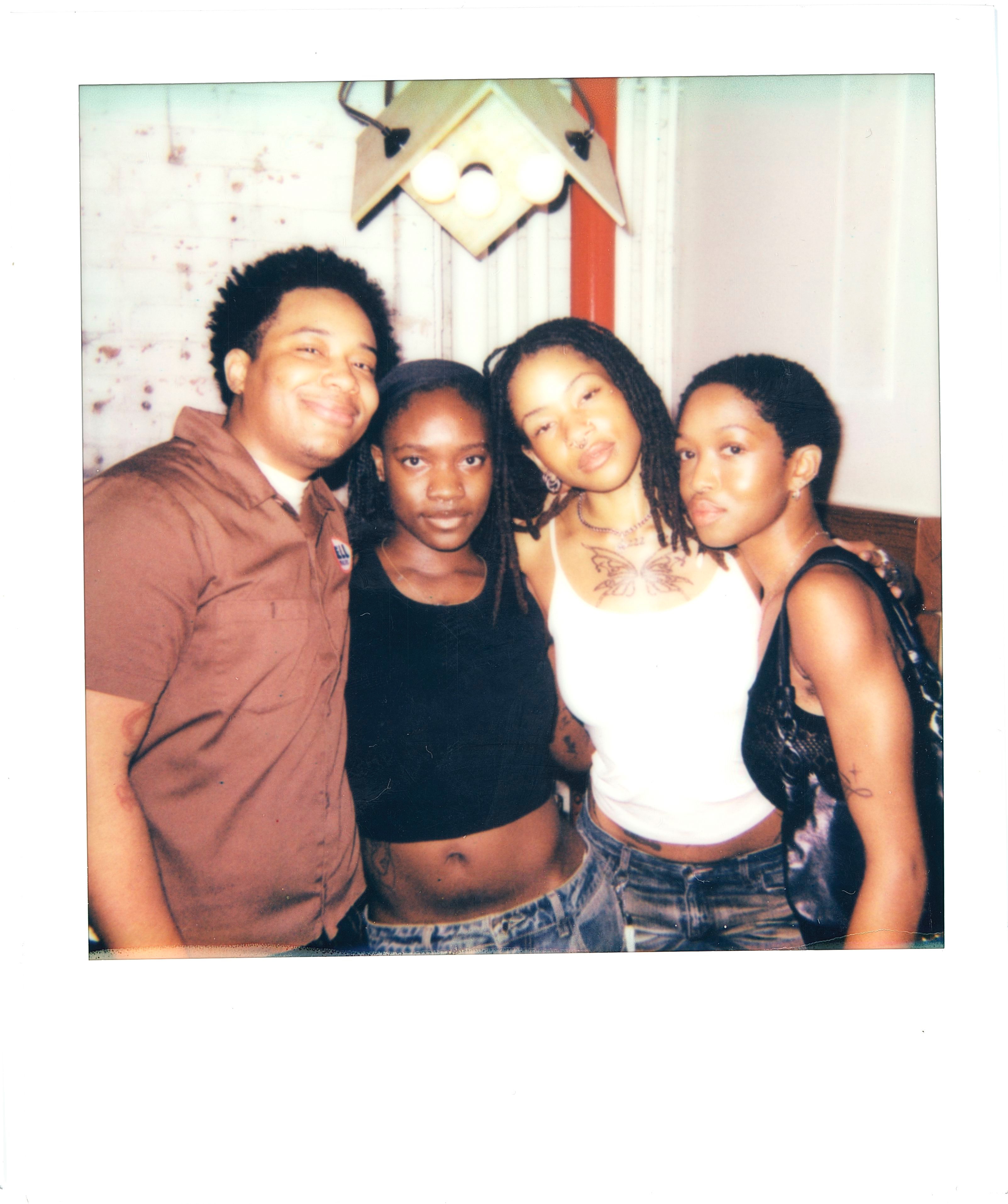

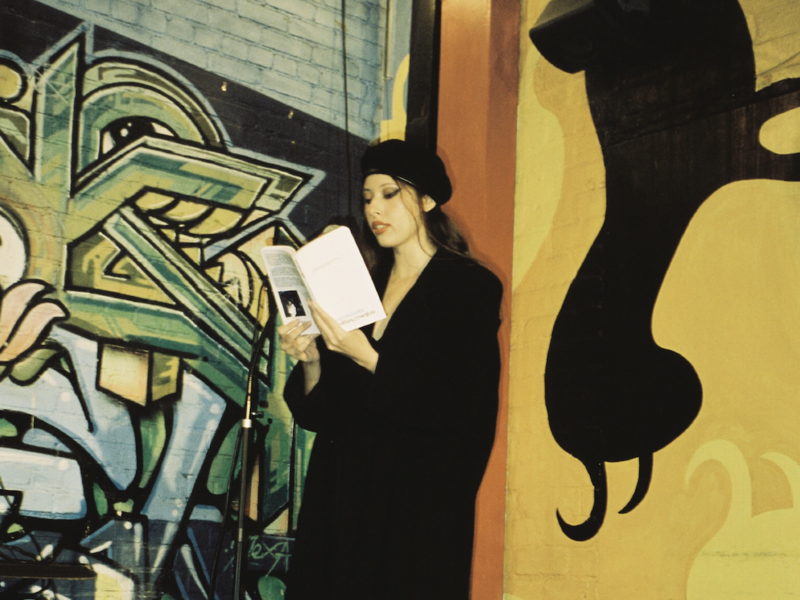

office caught up with Ahmad at her latest event to talk about authenticity, the NYC food community and food as a cultural tool.

So, how did this series come about?

I’m friends with Max Martin, one of the Cactus Store’s co-owners. We were talking, and he brought up the possibility of doing an event in their front space, which is this beautiful bamboo garden that leads to the store. They’d been wanting to do more food-related things, but there was really no infrastructure in place to support that—they needed someone to run it. So, I proposed a plan to organize these free food events that were geared towards inclusivity, and the team behind the space was very supportive of that. They ended up giving me total freedom to curate this series, and it’s been great. Everyone involved with the space has been really supportive.

Is there an overarching concept or theme driving the project?

I wanted to work with people who make great food, but also use it as a means of communicating larger ideas. Each of these chefs uses their work to highlight a particular region, connecting with their personal histories while exposing their culture to outside communities. So, with the series at Cactus Store, it’s really been about using the space as a platform, a new setting for these people to do their work. A lot of times, when chefs do their own pop-ups, there are so many burdens—paying for ingredients, finding a space, accommodating a group of people, and the million other stresses that come with putting together an event—with little financial return. So, we wanted to create a space where everyone had carte blanche to do whatever they wanted, without having to worry about all those pressures that can inhibit creativity.

At the same time, we wanted to extend that same openness to the people attending the events. This project is meant to be as accessible as possible; we wanted it so that people in the local community, who live there and may just be walking by, could stop in and enjoy the free food in this really nice setting. It’s definitely not some stuffy, “proper” food thing, where people have to pay for tickets or RSVP—we’ve actually been publicizing it mainly on community boards, operating more on a local level, waving curious passersby into the space.

How did you go about choosing which chefs to invite? Were they all people you’d worked with or knew personally?

Yes, for the most part. They’re all New York-based people from within my communities—not only in terms of food, but also activism—who work in similar ways as I do, using their cultural heritage as a foundation. But where a lot of the events I’ve done in the past have appealed to a sort of “downtown scene,” these are people who might not necessarily go to more scene-driven food events in the city—they might be working more locally in the other parts of New York. So, I wanted this project to serve as a kind of bridge, linking these different communities.

Originally, when we were talking about this project, the idea of immigrant food kept coming up, and how New York is this hub of immigrants who are able to assimilate while still keeping in touch with their original cultures, often by preparing traditional foods. People find ways to maintain that commonality with their heritage, no matter what, and I think all of the chefs involved, including myself, have had this experience, where you’re learning from family recipes, visiting the places they came from and bringing back new ideas or ingredients to work with.

Other series you’ve organized in recent years—the “Asymmetrical Table” series you co-curated with Ora Wise and cooked with Reem Assil, your residency last summer at Dimes—have been multi-course dinners with a stated emphasis on education. Is the same true with these events?

There’s still an element of education, but this is much more casual. It’s a sit-down, hang-out situation—partly because the garden’s not a huge space, but also because we’ve really wanted to encourage a sense of intimacy. Having said that, the format does shift with each event. For the first one, Anya Peters, who cooks Caribbean food under the name Kit an’ Kin, laid things out more in a buffet style. Kit an’ Kin is this very family-driven project—not only is she working with family recipes, but her whole family actually gets involved with the process. So, while she was inside making food, her dad was out front grilling.

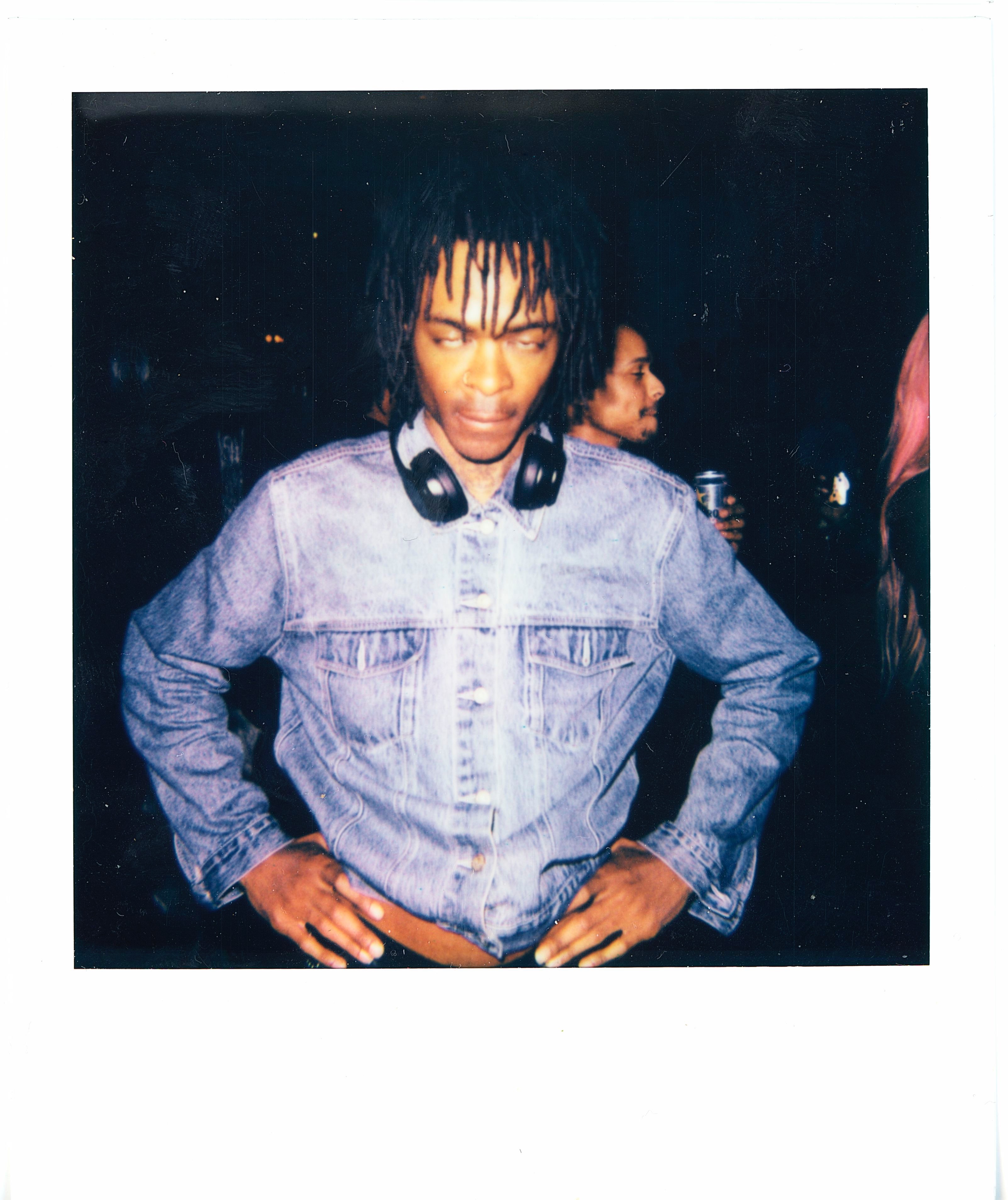

The second event, which was with Gerardo Gonzalez [previously of Lalito], was completely different. Gerardo is Mexican, his family’s from Jalisco, but he was raised in Southern California, so he wanted to do something more along the lines of Mexican street food, swap-meet-style. So, at his dinner, he was just standing there, dishing the food out and talking to people. He also got Jezenia Romero of Bunny Jr. Tapes involved, making a mixtape with all of this great classic Chicano swap meet music. So, for each chef, it’s really just about creating a vibe, an energy, that connects to their personal experience but is still fun and inclusive for everyone else. It’s a little more open and loose than your typical pop-up.

I’m surprised to hear you describing the events that way—I know you have a pretty strong aversion to that term.

I hate it. The concept itself doesn’t really bother me, but when I hear ‘pop-up,’ I think of retail shopping. The term just reeks of consumerism in this way that’s so gross to me. It evokes this spending environment: ‘Limited time only, go and spend your money urgently.’ It’s really the opposite of what I’m going for with everything I do concerning food, and especially with this series.

What might be a better terminology?

Well, I’ve been trying for so long to come up with a more appropriate phrase that people will still understand. Every time someone asks me what I do, I have to explain to them, where I’m like, ‘I do dinners and lunches in temporary spaces…’ ‘Oh, like a pop-up?’ ‘Yes, like a pop-up.’ [laughs] It’s a tough one to figure out. So far, for Cactus Store, we’ve been calling the events ‘free lunches,’ which isn’t my favorite title ever, but I haven’t been able to think of anything better, so I’m running with it.

You served as the featured chef for the third installment. Generally speaking, in approaching one-off events like this, do you use the opportunity to try out something new? Or are there certain recipes you lean on as standbys?

It really depends on the context. Last week, I did a dinner for the Rauschenberg Foundation, and the menu wasn’t Palestinian at all—it was actually a Japanese devotional cuisine called Shōjin Ryōri, which I’d never cooked publicly before, but was something I’d always wanted to try. So yes, sometimes the event becomes an opportunity to branch out. But at the same time, I hadn’t had the chance to cook a Palestinian-centric menu in New York since last November, so I was really into the idea of doing an all-Palestinian thing. I wanted to keep it somewhat traditional—or maybe not so much traditional as representative. I like giving people a good sense of Palestinian food, but I also try to leave some room for expansion, some personal touches.

That seems to be true of the other chefs as well. Everyone’s work has some element of personal interpretation, be it in reframing older techniques or in reflecting present circumstance: incorporating local flavors, seasonal ingredients and so on.

Definitely. For me, keeping some level of tradition has to do with being educational. I want people to be able to walk away from the meal and say, ‘I’ve had Palestinian food.’ Most people haven’t had Palestinian food, at least knowingly—those who’ve had it were probably told it was something else, or even from somewhere else. But having said that, even when I did my Palestinian dinners at Dimes last year, a lot of the menu was vegan, which is fairly un-Palestinian. So I still want to be able to honor myself, my influences and my environment. I think that’s true of everyone involved in this series.

There’s an interesting balance when you’re dealing with ideas of ‘authenticity.’ On one level, you’re dealing with cultural heritage, so there are reasons to work with these traditional recipes and methods—but at the same time, you want to allow yourself the freedom to be true to whatever you are. Personally, it’s important for me not to feel like I’m being pigeonholed as a ‘Palestinian chef.’ I’m a Palestinian-American person, an artist, as well as a chef and an activist, and I try to conduct myself in ways that are in line with my own sense of morals and ethics, which may or may not be in line with certain traditions. Honestly, I feel like it would be doing myself and my people a disservice just to make all of these recipes by the book. Most, if not all, of the chefs in this series are first-generation, and I think there’s a common experience there, where you realize that sometimes part of carrying on a tradition is allowing it to change.

So, what’s coming up next in the series?

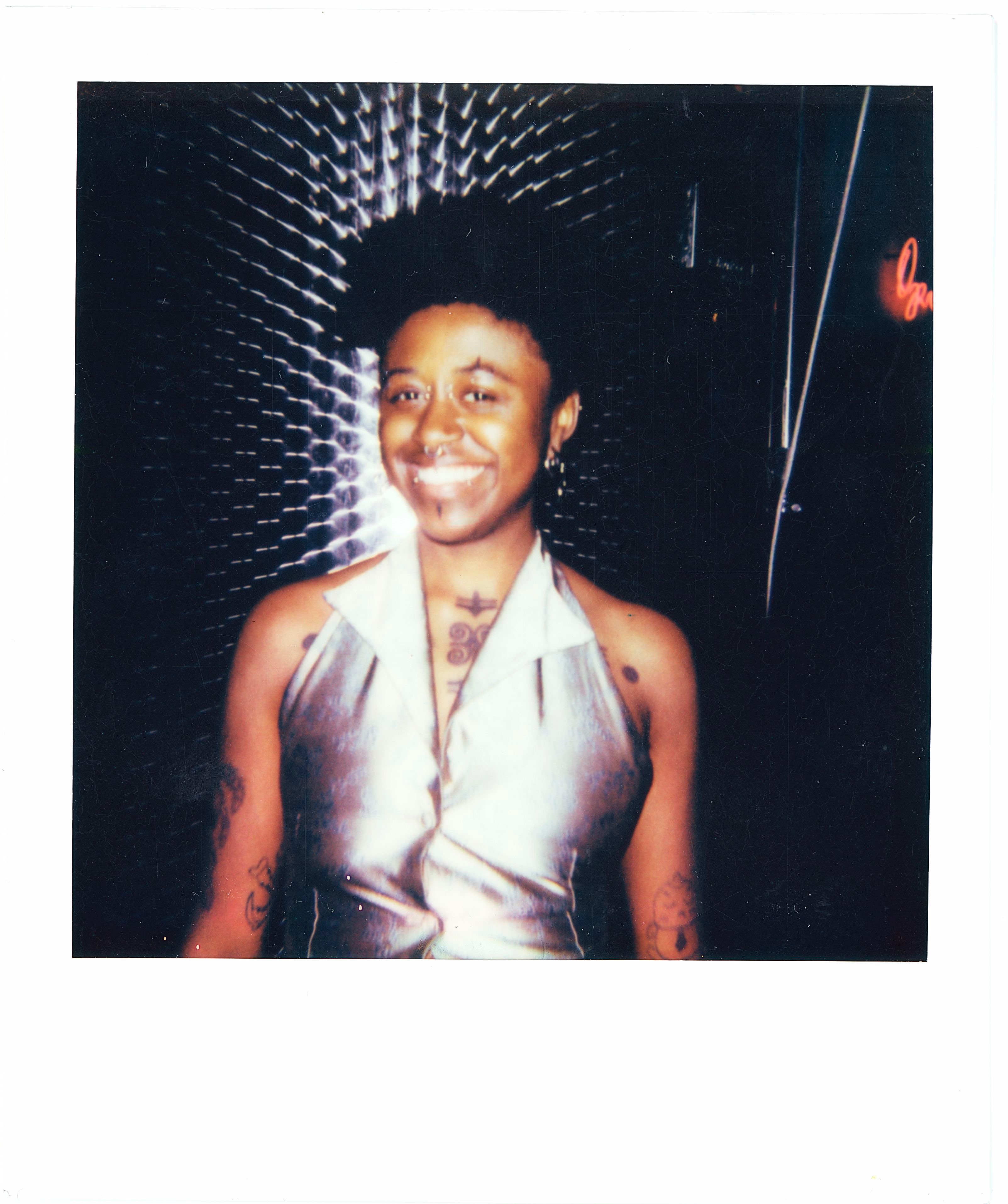

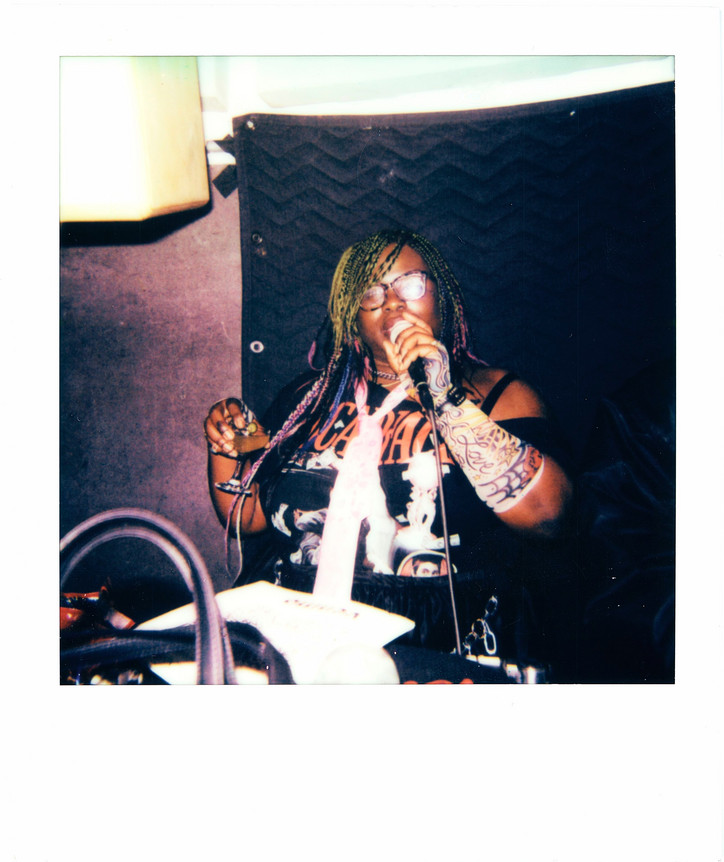

On October 7, we featured Precious Okoyomon, who does inspired versions of traditional Nigerian foods. She’s actually a poet, but also works with food by exploring things like candied dead bees, or delving into fermentation. I don’t think she has done very many pop-up events like this, so it was interesting to see how she brought a few friends with her to execute her vision. Then on October 14, we’ll feature a woman named Chakriya Un, who makes amazing Cambodian food under the name Kreung. Her story’s really interesting: she was born in a refugee camp in Thailand, immigrated to the US with her family, and started her pop-up series to help raise funds for a tractor for her family in Cambodia. I imagine she’ll do a cookout on the grill, but you never know. The last event for this season will be on October 26, and features a dear friend of mine, Sabrina De Sousa of Dimes, who is going to be preparing a vegan version of this traditional Brazilian stew cooked in a pumpkin, which I am very excited about!

For more information on the Cactus Store residency, including dates and times of upcoming events, follow @hotcactus_la or check here.