To Give With Abandon

Read our discussion with curator Carla Fernández below, where the artists discuss control, anonymity, and the necessary risks that should be present in art.

Juan Antonio Olivares— I was really happy to meet you because we both know Carla but our paths had never crossed. I always sensed a mischievous humor in your work, so I was glad to put a face to it.

Kaspar Müller— I recognized your face even though it was our first in-person meeting. I’d seen images of you with short hair and a broken leg.

JAO— Oh yeah...

KM— After that, we didn’t communicate much until Carla connected us for the show.

Carla Fernández— It was an easy decision for me since I’m close to both of you. For the first show in New York, it made sense to exhibit a conversation between two artists with some momentum. Juan and Kaspar share a sensibility despite having different perspectives, which is an interesting entry point for me.

Often, Latin American art is shown with a focus on folklore or colonialist mockery. Juan studied at The Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, proving you don’t need folkloric associations as a Latin American artist. Conversely, Kaspar’s work is very folkloric, creating interesting tensions and contradictions. The netting of Kaspar’s Catapult was made by an artisan, blending these ideas without categorizing what Latin America is. Hopefully, it moves towards a global discourse.

Devan Díaz— Juan, in the show’s press release, you mention a conceptual image being an oxymoron. Did the AI text-to-image generator make a conceptual image possible?

JAO— 'Conceptual' is a loosely used term today, often meaning “looking smart.” I'm inspired by 1950s and 1960s conceptual artists who questioned art’s materiality. Many of them were performers and theoreticians before making objects.

A classic conceptual image is Joseph Kosuth’s "One and Three Chairs," where you have the definition of what a chair is, the image of the chair, and then there’s the physical chair. It represents the essence of a conceptual image because it involves three inextricable parts. The AI image generator I worked with takes a text prompt and turns it into an image by analyzing the prompt against a large database of existing images the software has learned from—much like a human brain does but with quicker and generally more awkward results.

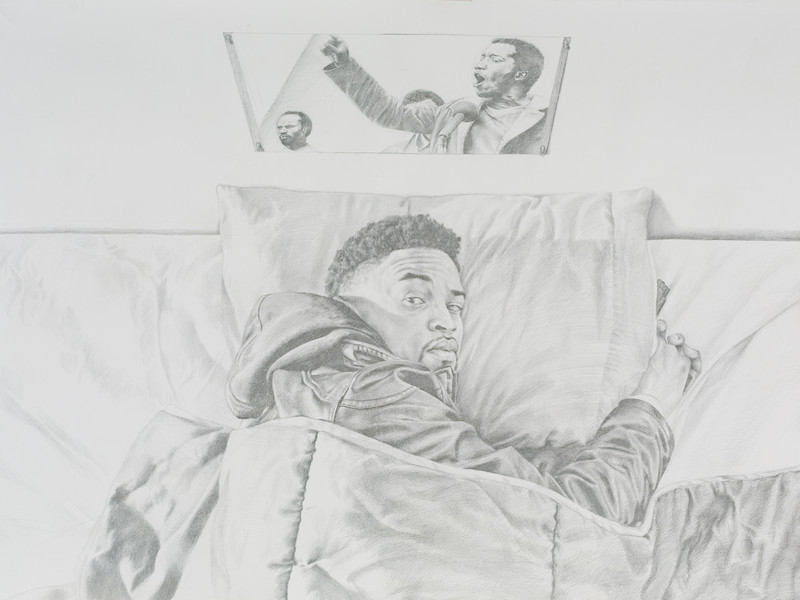

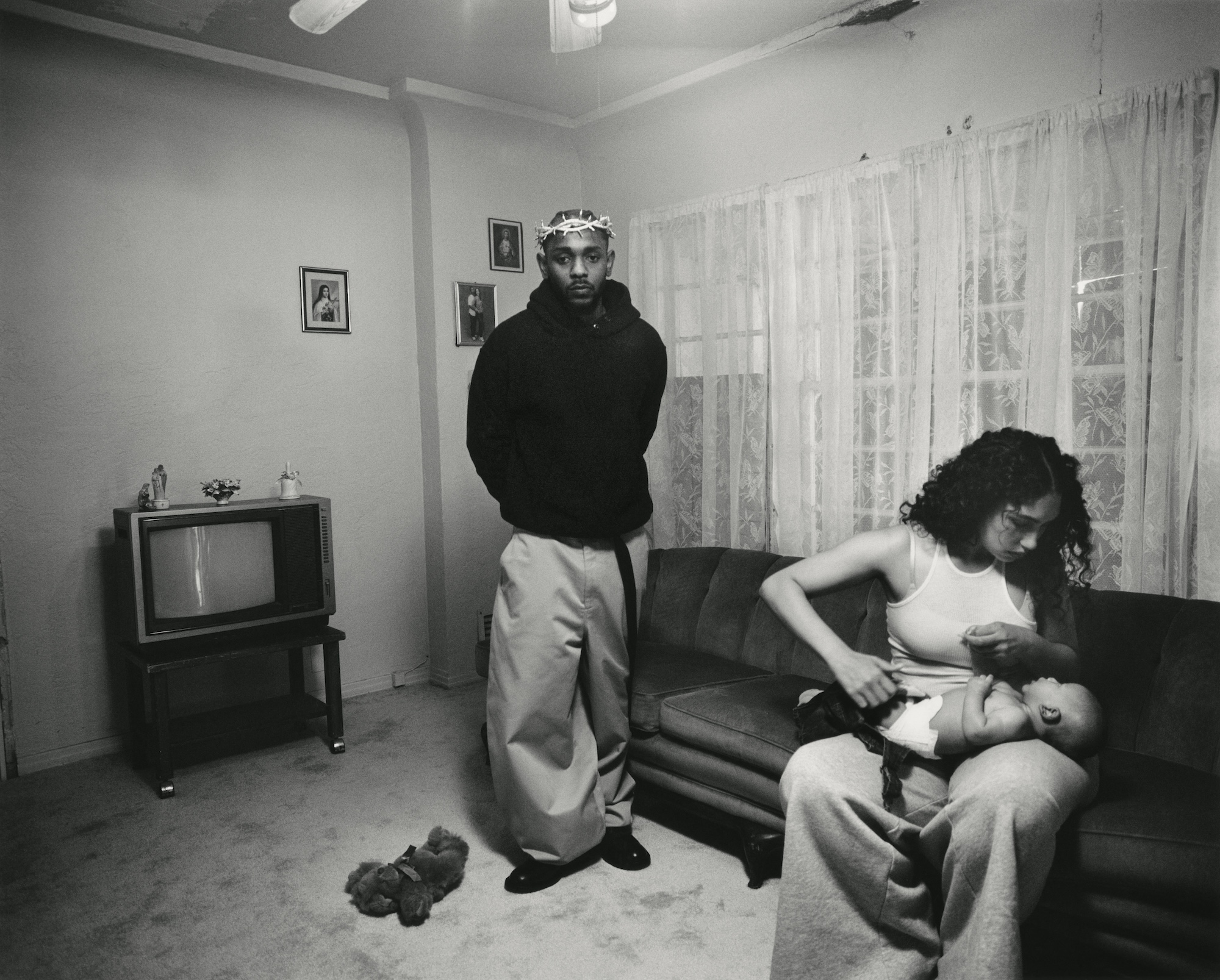

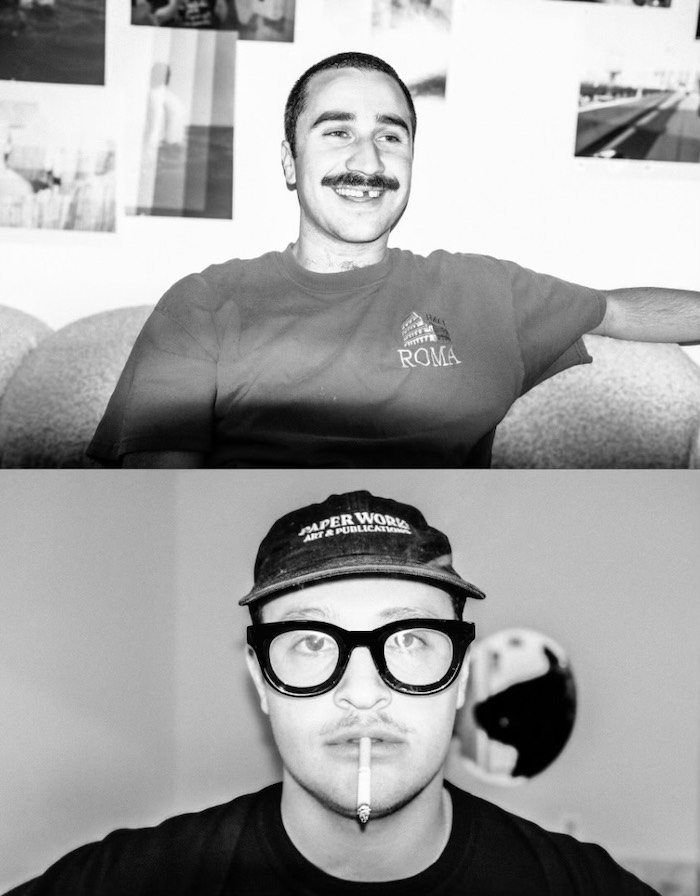

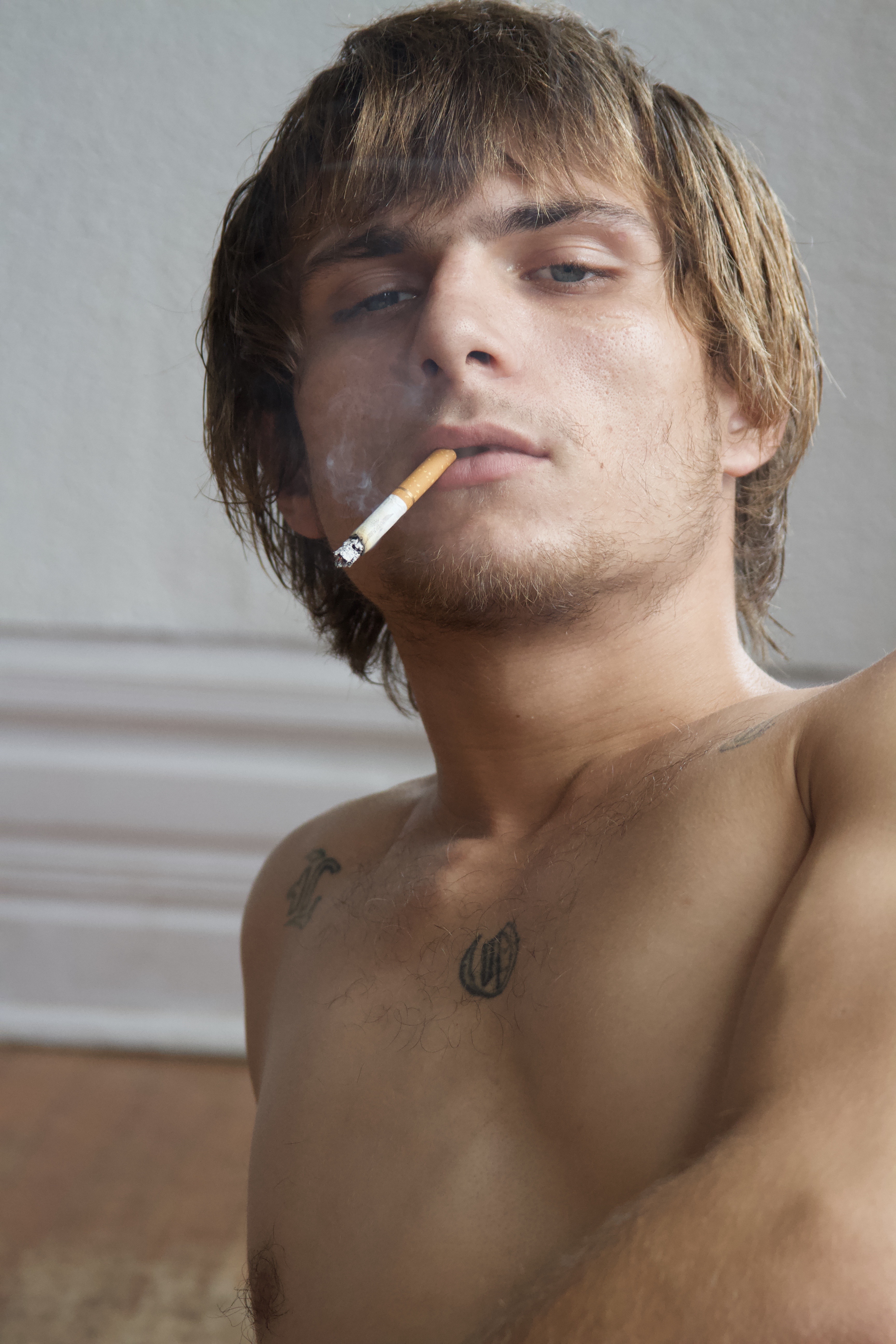

KM— The machine’s faceless theme, produced from input, interested me when I created these figures now exhibited as paintings. They started as reference pictures for the straw man I exhibited at Basel. My kids took pictures of me posing in our living room, and using an Apple AI tool, I isolated these figures. Suddenly, I had emoticons of myself without my surroundings. Completely unrecognizable as me. This byproduct became part of my straw man conceptualization.

JAO— I love knowing that. I didn’t realize how you isolated the figures. Our awareness of the readymade connects our work even more. The readymade is a traditional medium at this point, it’s over 100 years old. Isolating something by clicking on it, something even a kid could do, has a ready-made aspect.

KM— Most people discover it accidentally.

JAO— There’s anonymity in your images. I wanted to release my agency as an image maker by using an image generator because there’s freedom in anonymity.

KM— In the images, when I put my hat over my head, the figure becomes faceless. The audience can’t tell who it is and I couldn’t see either. Pointing into the void, I was in darkness, able to point towards nothingness with more determination.

The circumstances of these images make them highly ambiguous. I gave away control, not seeing what I was doing, and embraced the digital realm's freedom. These images weren’t the final product, so there was no pressure. I like recycling or reusing byproducts in the process.

DD— How are these images affected by the objects in the room?

CF— AI, like emoticons, are digital tools. If you think about what will remain when we’re gone, like the sculptures, it creates tension with the images. Language and technology change constantly, and eventually everything becomes obsolete. Sculptures bring realism to the digital conversation. Two vectors exist—the horizontal digital realm and the vertical heaviness of catapults, glass, and metal.

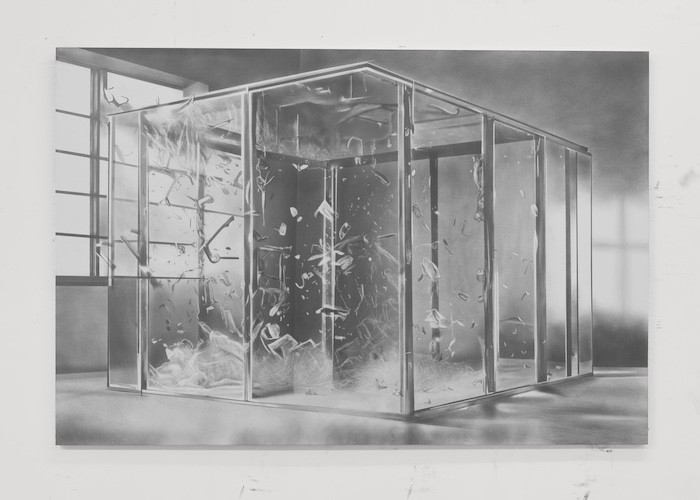

JAO— In an early conversation about the catapult with Kaspar, I felt a welcomed risk factor. We discussed whether it should be on or off, its destructive capability. The ball and chain I made for this show is also functionally restrictive.

CF— Medieval surveillance restrained bodies, and now emojis constrain identities. Both forms of control.

KM— Creating this catapult, breaking it down to its simple function of destroying, involves absurdity. Wine, a Christian symbol with economic loss when spilled, is controlled by an algorithm. I programmed the catapult to go off unpredictably, known only to the person controlling the code.

JAO— Kaspar’s images, which I found humorous, seemed like positions of punishment. The obscured, hooded figure felt like bondage, which felt unexpected from you.

KM— We also talked about financial domination, a popular topic for artists.

JAO— In today’s financial climate, there’s precariousness alongside a pretense of stability. Exploring financial domination’s humiliation, similar to art’s unreciprocated transaction, was interesting. Art gives itself to the viewer with abandon.

DD— Is there humiliation in showing art to an audience, or is that the wrong word for public exhibition?

KM— I’m not bothered by it. I like giving it away, relinquishing control. Artists invest energy and sensitivity in their work, and giving it away means losing control. It’s a dynamic we can’t escape, but my goal has never been to remain unharmed.

JAO— The risk aspect is present in the show. I was expressing frustration with what I felt was a very tame New York art world. It feels like there’s no risk because people are afraid of things not selling. I don’t think either of us were trying to shock or ruffle feathers but expressing the precariousness of this world.

The Panther is on view through June 8, 2024 at 49 Walker Street.