Jeanine Brito Paints The Grumpy Girls With Desire, Gore, And Frowns

How is The Grumpy Girls a departure from your previous shows?

My last show was really a linear narrative and The Grumpy Girls is a bit more of an abstract narration. There’s not a clear beginning or a conclusion to the story. It’s giving you the different pieces and you can arrange it in whatever way speaks to you.

It’s a bit of a technical challenge for me. I had never worked with multiple figures this way before, especially in the large works. I would say it’s an evolution [of my previous shows] I’ve been working conceptually with the same ideas… motherhood, sacrifice; this before and after of motherhood.

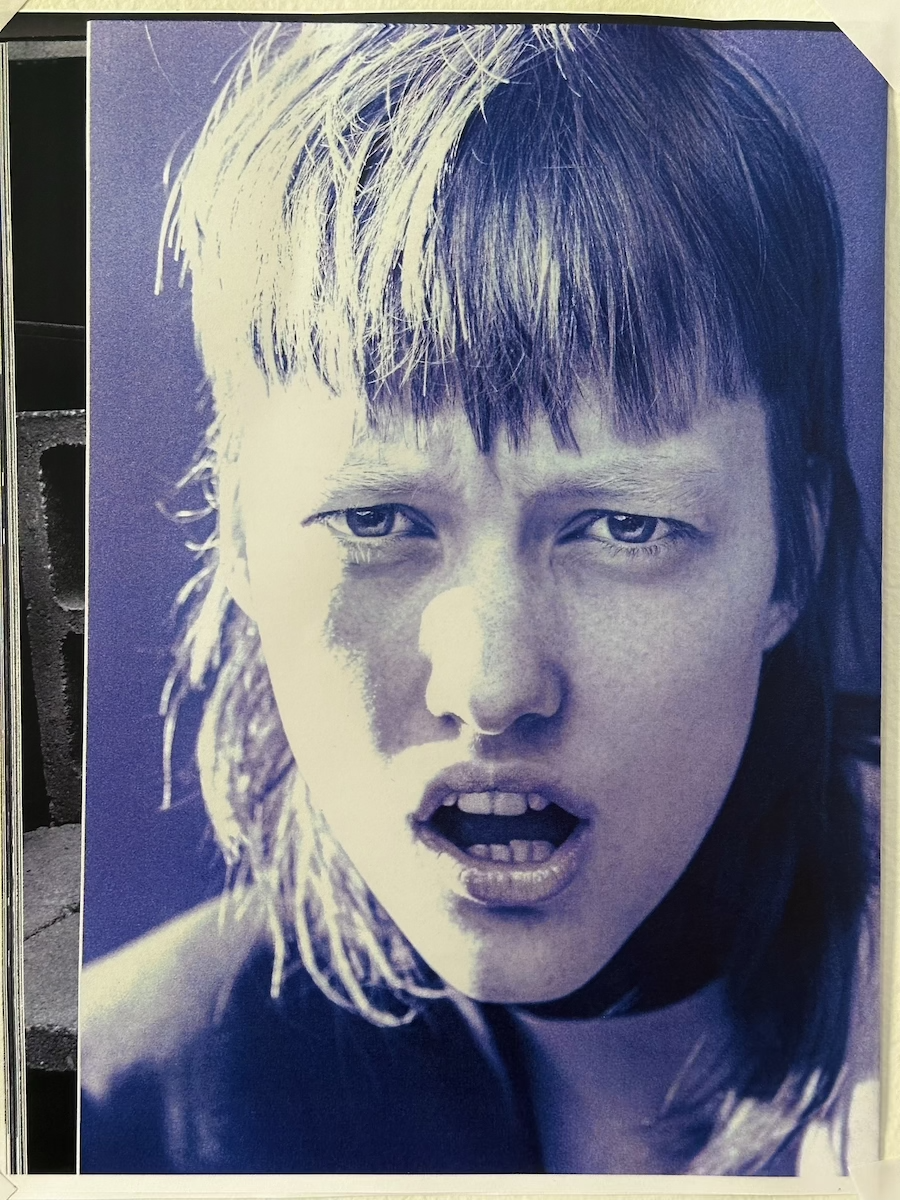

It seemed very crucial for the girls to be grumpy. Why is it important for the grumpiness?

It takes this very serious idea and winks at you a little bit. I like this idea that they’re doing this labor, they’re braiding this hair or preparing the scenes, but they’re not thrilled about it. There’s reticence, they’re begrudgingly doing this work in service of the play, the film, however you see it.

Having them openly frowning is important for that to convey their unwilling participation. And also frowns are very fun to paint. It’s fun to paint these frown lines. More traditionally in representation of women in painting, we don’t really see a lot of anguished, frowning faces — that’s more rare.

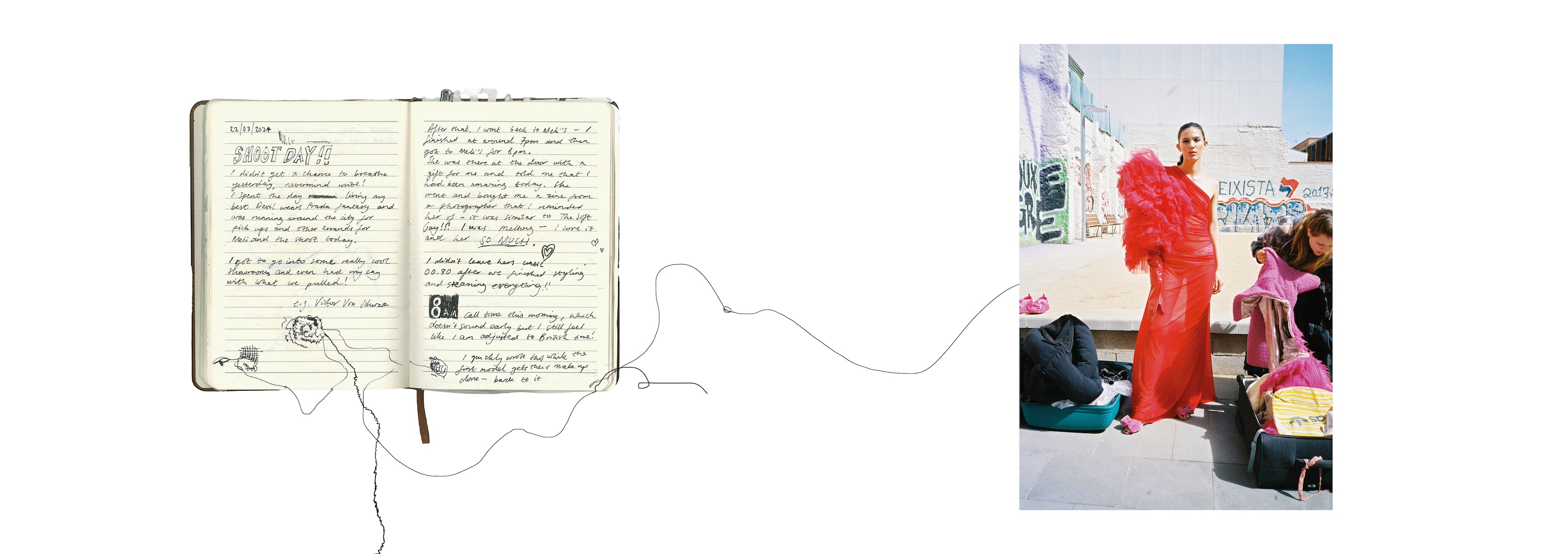

What was the creative process?

It started with a sketch that I made in the summer. The sketch became the artist, the winged figure and she was initially facing the viewer and looking very stern, very grumpy. And I like this defiant gaze. I kept developing that sketch and started building out these other iterations of that character, so the girl and the mother. And at some point, I realized they all had to come together. That’s when this fourth figure emerged, this nude self that they’re all sort of working in service of and the rest of the show was about paintings that would support the storytelling of these four works.

There’s a lot of technicolor theater and costuming references. How did you choose those cross-references to come across in your work?

I really like that era of cinema. The Red Shoes is something I referenced in my last show as well and I continue to go back to. It’s such an interesting story and thematically it really aligns with this show in that it’s really about whether art making and a full life can be compatible, which is the question that I’m asking with this mother figure who's disrupting the braiding scene with the scissors. What are the elements I need to let go of to make space for this new identity? What things need to be sacrificed to be a mother? And what of those things need to be sacrificed to be an artist?

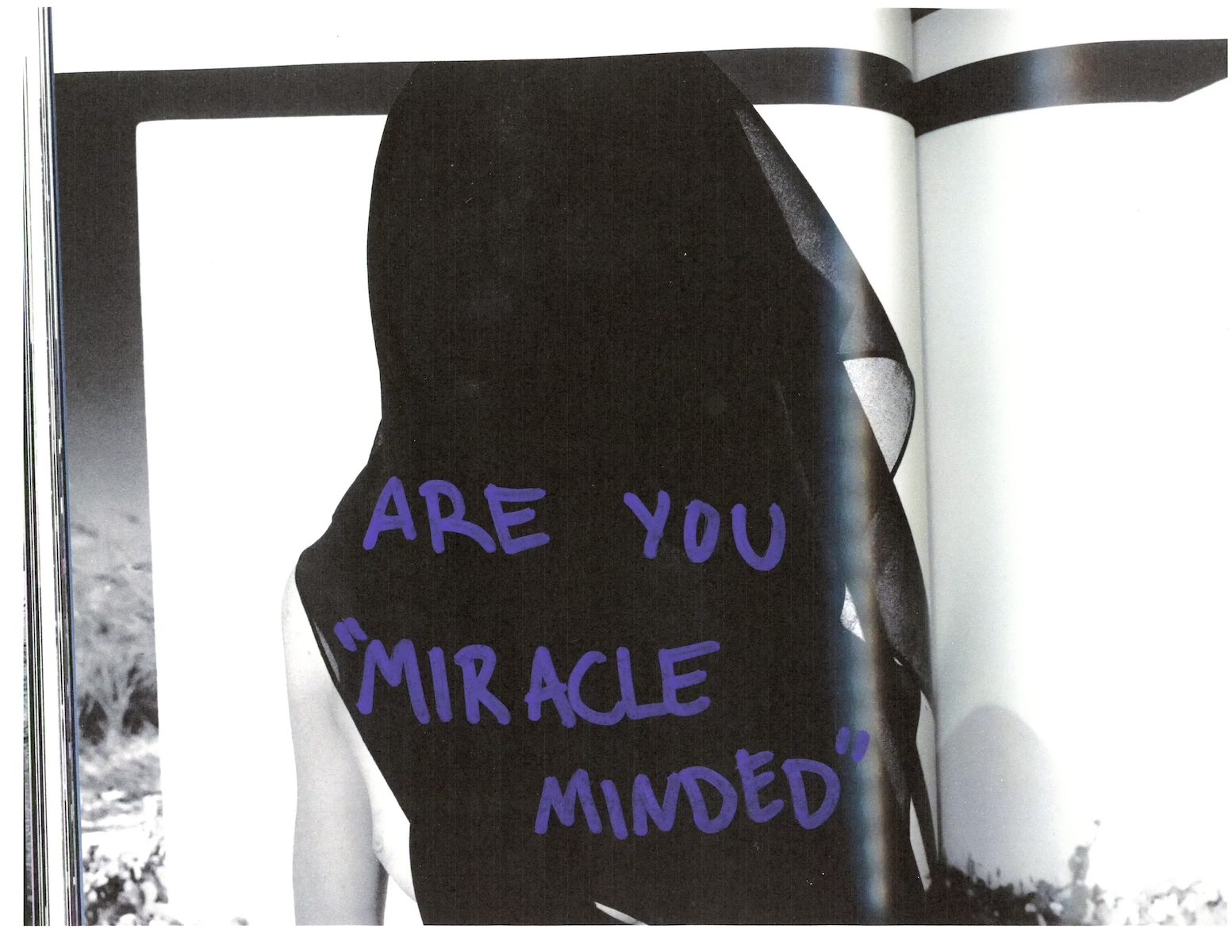

What conversation are you having with yourself through the paintings? Like presenting yourself as a visual artist and pulling back the curtain… what’s going on internally with that?

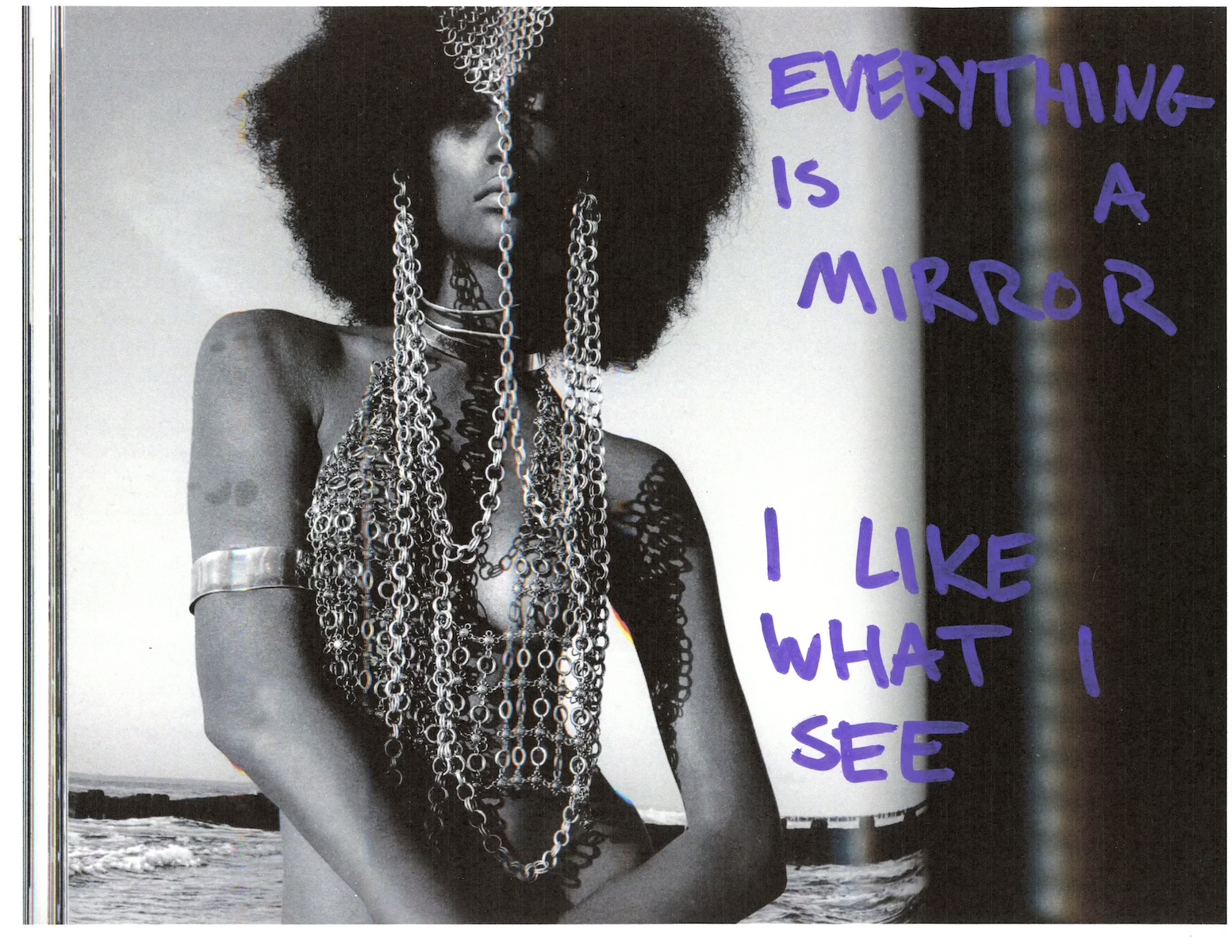

There’s a degree of vulnerability. But there’s still the veneer of guarding myself, I suppose. The nude figure is most representative of that — laying there like a beach siren nude, but she still has the [opera] gloves and is still wearing the makeup. It’s sort of me saying I allow myself to be vulnerable to a point in my work. And I think that’s where the camp, winking, tongue and cheek element plays in too, because I’m taking these very serious, heavy ideas — it’s adding something acidic to something very fatty.

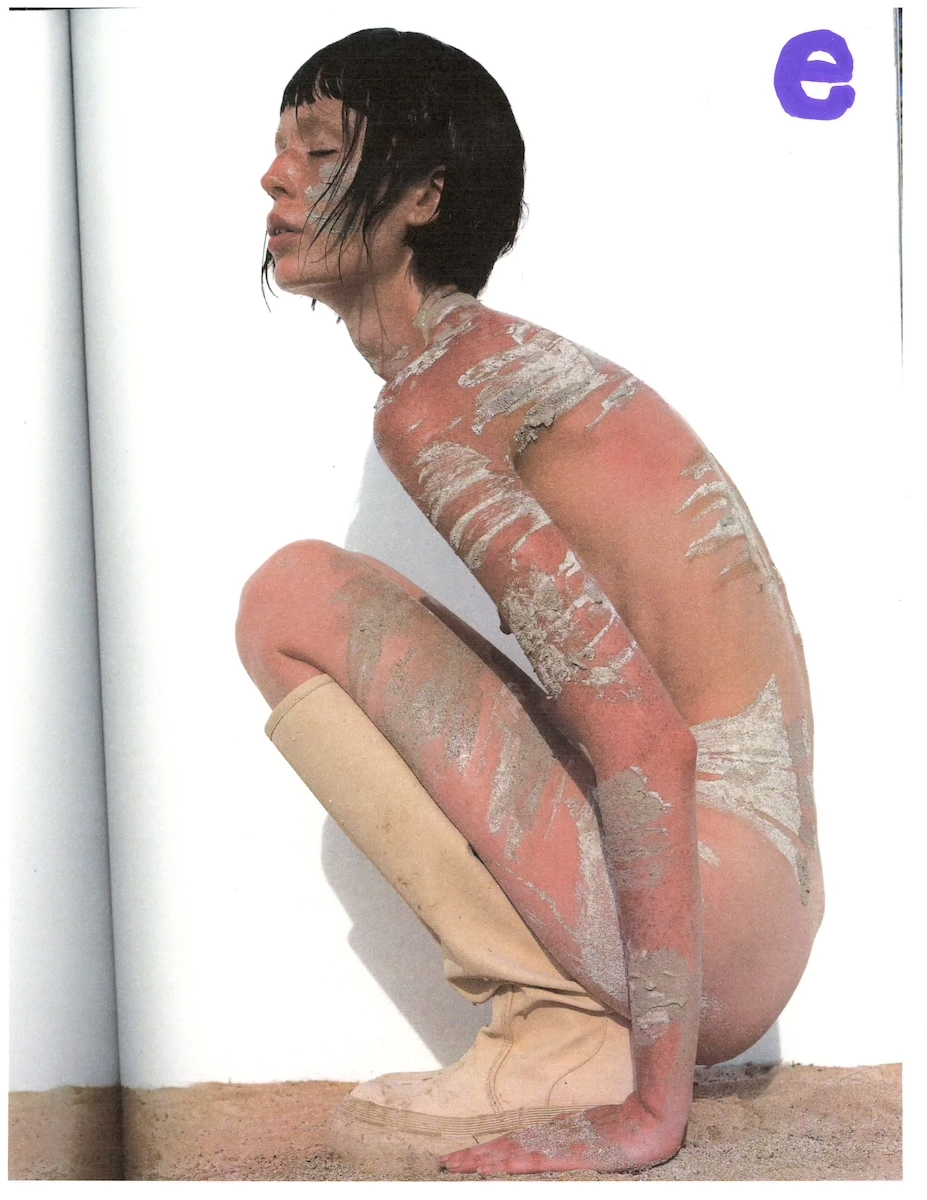

Especially with these three archetypes, trying to interrogate different aspects of myself. The blood letting one especially is me unpacking my vanity and my relationship to beauty culture and beauty rituals. I’ve seen so many videos lately about simplifying your skincare routine and I used to be a 12-step [skincare] girlie and I honestly don’t know if it was helping. Historically, when you look at these really dangerous beauty practices like lead face paint, those women never knew they were hurting themselves at the time. While the other archetypes are a bit more reflective, the mother is hypothetical — I’m imagining a future version of myself.

It’s definitely portrayed that there’s this cost to girlhood or womanhood. What was it like to portray that cost?

That’s a perpetual tension in my work. The desire to paint a beautiful figure, but to also represent myself in a way that feels honest to me and navigating beauty ideals in painting and media more broadly. Having pubic hair in a painting, I heard from other artists that they were discouraged to have women’s body hair in paintings and then at the same time, my figures don’t have armpit hair or leg hair. I’m battling my own internalized ideas about beauty standards. As I make more work where I push myself to resist [beauty] ideals more, I notice I become more comfortable in my own body in my real life.

How has your previous experience in fashion contributed? I noticed the opera gloves in the pieces…

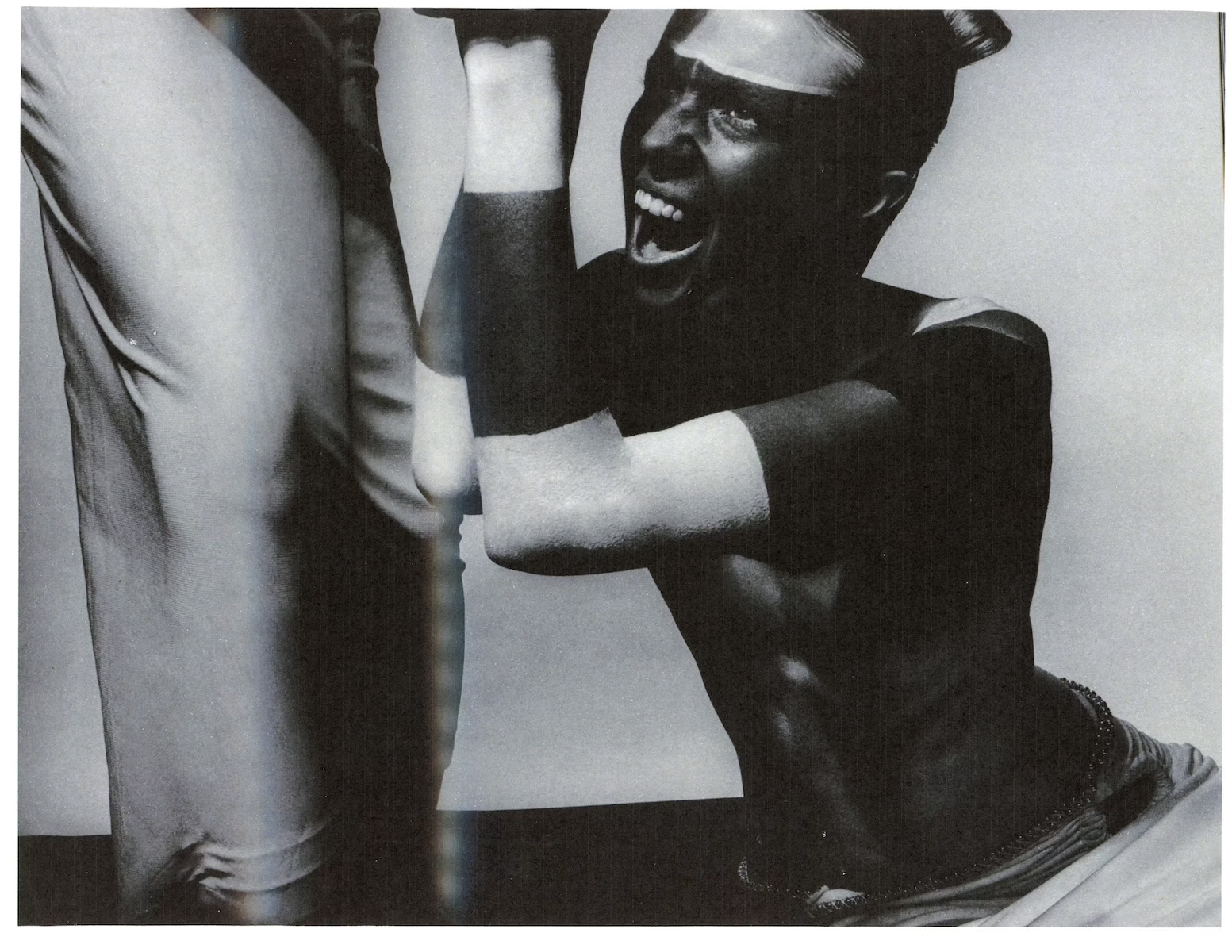

Costuming is very important to me. It’s very fun to paint dramatic folds and poofy skirts. The costuming can tell so much of the story for you too. The artist is the most free version of myself so she has these wings and this tiny little tutu that’s a contemporary version of a tutu and it shows her legs and her butt.

The gloves have been a barrier layer, there’s sensuality to the [opera] gloves, but actually whatever is being touched by the hand in the glove is not being touched by the hand itself. I like the sensuality of that restriction. I like to have these feminine elements in contrast to blood and meat, these more grotesque images.

What made you think Oh, I’m going to have this ballerina paint this meat carcass? What was the symbolism behind the carcass? Is it a meditation on femininity?

She’s painting a set piece. So the idea is maybe there’s a slaughterhouse scene that we’re not seeing. But also it’s a nod to my previous work where I’ve painted a lot of meat. She is the archetype that I identify with most at this moment. I like having her in this meta… her painting meat while I’m currently painting [her]. Meat in my work is a symbol for the body. Meat being decontextualized from a consumption context makes it feel a lot more fleshy. This metaphor of earthly flesh, decay, there’s an ephemerality to it — it’s fresh right now [the meat] but it won’t always be.

It’s pulling back the curtain while also showing the stage. How did you manage to capture both?

That’s the duality of these feminine touches and having them directly alongside bodily horror imagery. That it’s staged suggests there’s an artifice here. The surfaces are really smooth and they’re varnished with this fat and finish that gives them this weird quality that’s almost like you’re seeing it through a screen or a piece of glass. It’s a performance — an image that’s not totally solidified. There’s a degree of removal.

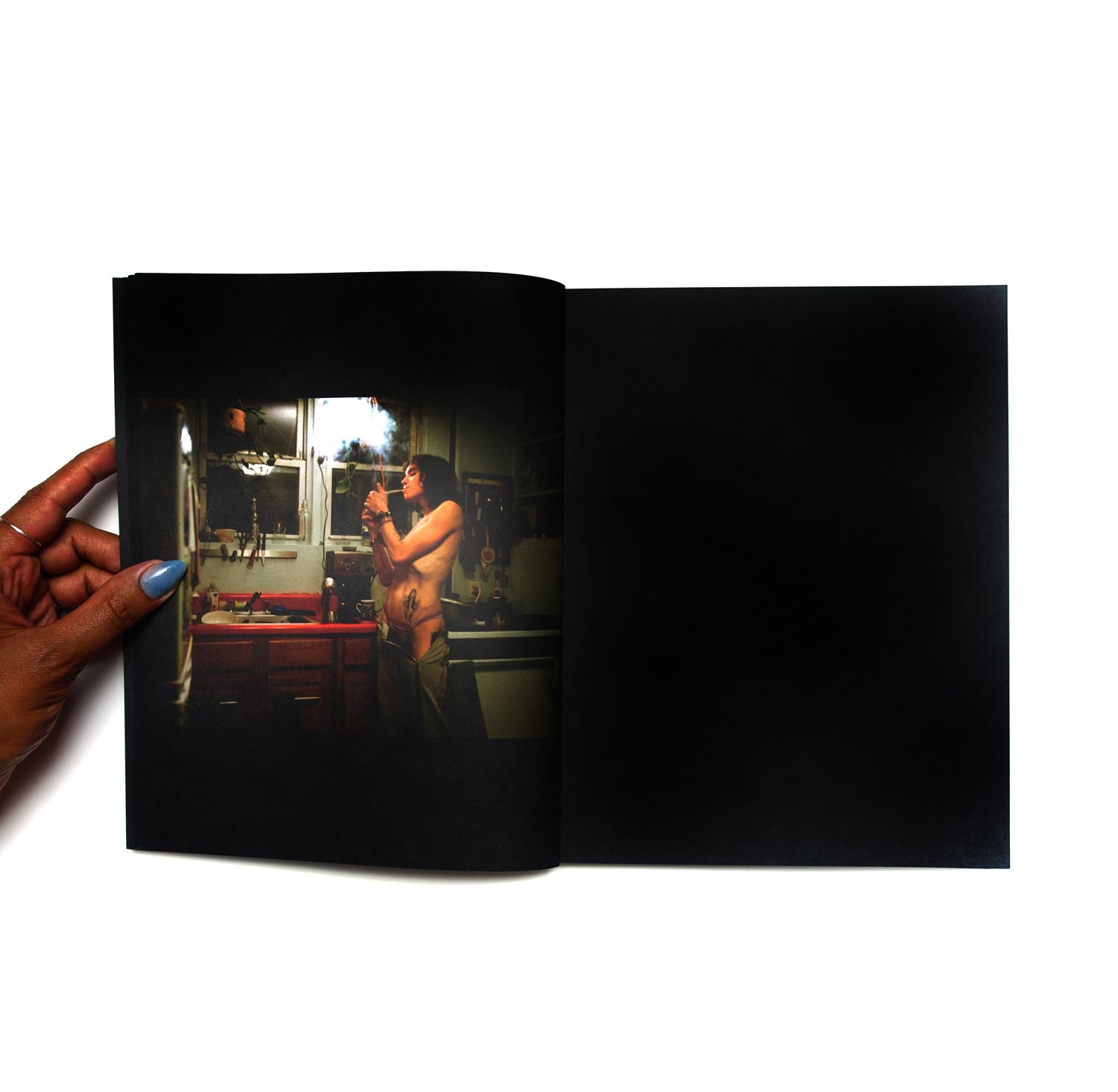

Out of all the things you could paint… what’s so interesting about self-portraiture to you?

During Covid, I was stuck at home and this is what I had to work with. It was also a way to project myself into fantasy settings and scenarios that weren’t accessible to me at the time because we were locked down. That’s the origin and now it’s really about trying to know myself, to be corny. I discovered so much about my wants and desires in making these paintings. The things that I’m unpacking or saying at the outset of a body of work develop and surprise me by the time I finish it.