Jen Awad Won't Stop Daydreaming

Awads new single drops today, be sure to check it out wherever you can.

Stay informed on our latest news!

Awads new single drops today, be sure to check it out wherever you can.

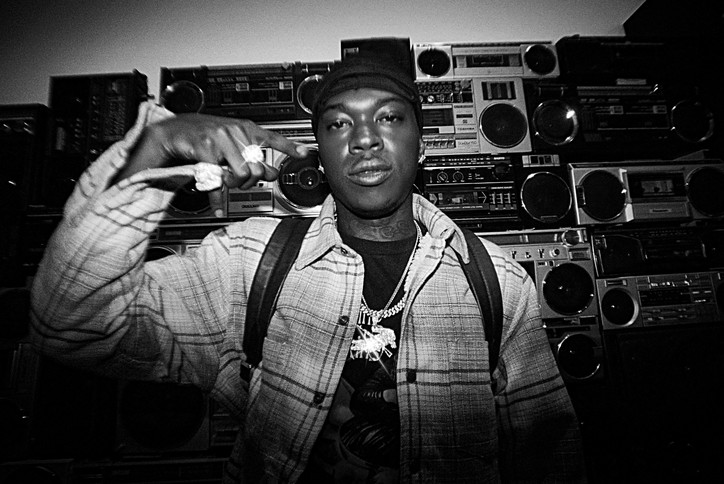

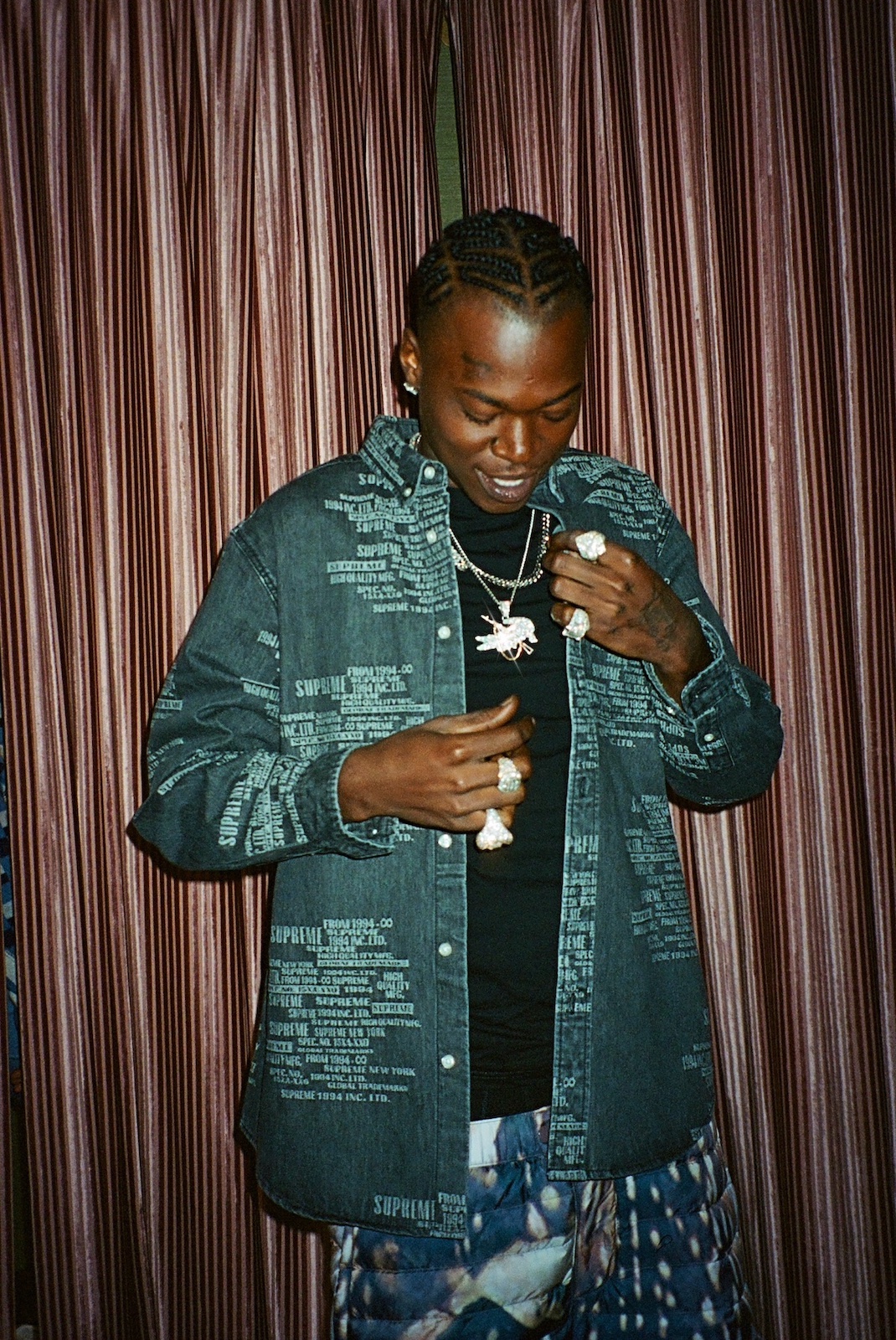

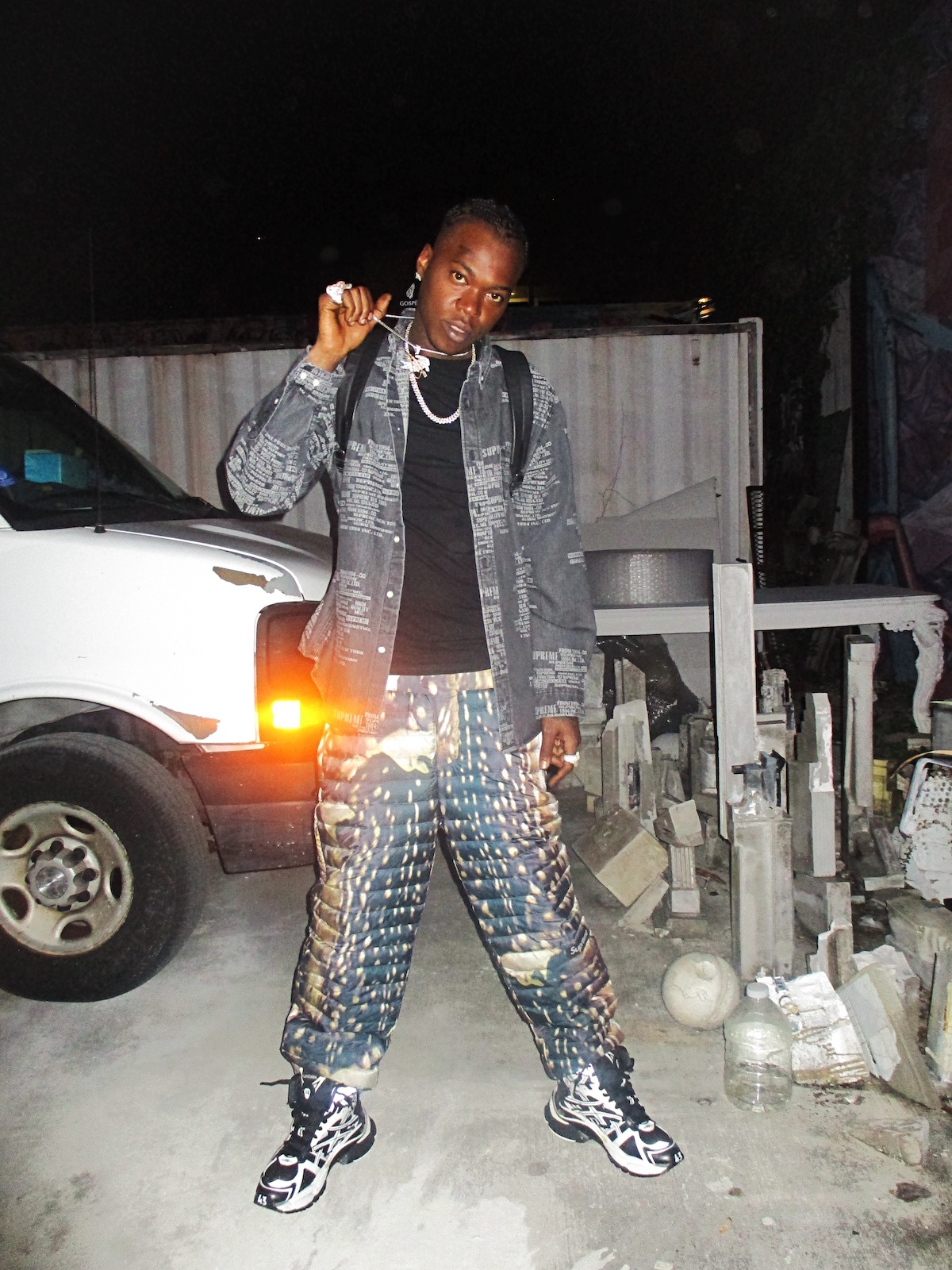

office caught up with Skillibeng ahead of the release of his newest single and his upcoming Mr. Universe album. Read our conversation below.

Hey Skillibeng! Where are you right now?

I’m at home in Jamaica!

How often are you at home these days?

It varies. I've been resting for most of last year, the year before it was a bunch of traveling. It was 50/50 with being home and traveling.

What’s your favorite place you’ve traveled to?

In the States — Miami, and New York. I love LA too. I love it.

How did music start for you? Was there a moment where you decided you wanted to be a musician?

It was in my latest days of high school. Actually the last year of high school, that's when I decided I wanted to become an artist.

Who were some of your early influences?

I looked up to everybody. I definitely have main influences, though. Vybz Kartel, Popcaan, Mavado, Aidonia. I listen to a lot of rap too. So I listen to Lil Wayne, Future, Young Thug.

You said in the past that you wanted to be a household name one day like those artists, and now you’re on your way. How does it feel watching your dream actually come true?

It's crazy, because everybody thinks it's something out of the norm that's happened. It's just like me doing what I do best, which is just creating music and watching everything else come to life.

Now that you have introduced a lot of people in the US and internationally to Dancehall, what would you say is like the heart of Dancehall? What do you think makes it a special genre?

It’s the language and it's the culture. How small the island [of Jamaica] is, but how relatable it is to the rest of the world. I want Dancehall to represent Jamaica and the culture, but also music overall because Dancehall is actually a genre that mixes with a lot of different genres. It is actually connected to a lot of different types of music in the world and it's also a Jamaican thing.

Tell me about the upcoming single and the album. What inspired this project?

The upcoming single — I was in England for Wireless [Festival] and I had a couple of meetups with some producers and P2J was one of those producers. That's how the upcoming track that we're about to release came about. And the album, the name is Mr. Universe, so it's just me showing the world that you know, I'm just a Jamaican kid who is very relatable through music internationally.

Speaking of Mr. Universe, you've collaborated recently with a handful of artists from other countries, including some American artists. How has it been to collaborate with artists from other genres, and is there anyone you haven’t collaborated with yet but want to?

The thing is, as music goes by, I don't really choose who I collaborate with. It's a natural thing, you know, if I like a person's sound or flow or something, and the label comes across to me and say, “hey, you could actually get a feature with this person,” I say okay. So it's really a natural thing. I don't really differentiate between artists, as long as they're actually good artists that take music seriously and sound really good.

But yeah, Lil Wayne or Future. Those are some of the artists that I haven't collaborated with yet internationally. As a kid, the only person that I really wanted to collaborate with was Vybz Kartel, and now I already have two Vybz Kartel collaborations. And I've already collaborated with the queen of rap Nicki Minaj. Twice.

How did those collabs with Nicki come about?

Oh, that song was just hot. That song “Crocodile Teeth” was literally just hot. I think Drake had told her, “you know that this kid is ripping the streets up, he’s going places, I think you should jump on that track.” And she actually did, and she put it on her mixtape.

You've accomplished so much already, but there's still such a long future ahead of you. Where do you hope to see your career in the future?

As we initially started, with the conversation about household artists — that's the main aim, you know, to be respected musically. For the people to know that music is just my thing, and accept me even 20 years after, for me to be able to still drop a track. It's like a supermarket. People gonna go to the supermarket that everybody trusts and they got the products they want.

So me as an artist, I’m trying to differentiate myself from other artists who might come up and fade away. That's not what I'm trying to pursue.

Thank you so much for making the time for this conversation. Congratulations on all your success and I look forward to seeing where you go.

Respect. It's already past the first month but happy new year, may it be a very prosperous one. Stay focused.

Thank you, you too.

When did music become a thing for you?

Music was always a way to feel connected to Lebanon. I was born in Tripoli, in Lebanon, and moved to London when I was six years old. I remember my mum playing Fairuz in the morning, and Umm Kulthum at night. When we’d go for drives in the car together, we’d listen to Wael Kfoury, Najwa Karam, Elissa, Nawal Al Zoghbi…

I was obsessed with Star Academy, this 24-hour Lebanese TV channel kind of like the X Factor, where you’d see singers doing vocal exercises, note reading, music theory. I actually auditioned a couple of times to go on the show when I was younger.

I was also really into performing arts and musical theater like the Rahbani musicals. I would secretly go to ballet at Urdang, a performing arts college near Farringdon, until my dad caught me with my ballet clothes one time and stopped my pocket money. So I never really had the opportunity to explore that side of myself when I was younger.

Would UK sounds play into that, at all?

I didn’t actually know who the Beatles were when I started Music at school. Or Amy Winehouse, Madonna, Destiny’s Child… none of that! I got heavily bullied for it. People weren’t curious about the music I liked, and there wasn’t much room for songs outside of the curriculum anyway.

Okay, wow. I didn’t realize that!

Yeah! This is something that has stayed with me throughout the years. It’s been a constant chase for a community that’s connected by Arabic music.

Did trips to Lebanon ever bring a sense of reconciliation, then?

Sort of. I’d take vocal training classes there over the summers, but I felt limited to a specific style. It was very gendered: the repertoire for men was songs by Zaki Nassif, Nasri Shamseddine and Wadih El Safi. I just wanted to sing Carole Samaha! I was much more drawn to the female sound, the softness and gentleness.

What’s been your approach to learning and growing as a music artist?

I think on the one hand, I’ve often tied my musical talent and ability to qualifications, so I was always chasing this idea of being formally trained in Arabic music, as many traditional artists do. I do really enjoy focusing on traditional Arabic singing, for the way it highlights the maqams,* and for how long and sophisticated the finished piece turns out. So after I graduated from university, I moved to Lebanon for a longer period of time to start vocal training. I took courses at USEK, the Holy Spirit of Kaslik with Ghada Shbeir, who specializes in Arabic, Syriac, Arameic music and muwashhahat(a poetic form that uses complex rhythms originating from Al Andalus).

But at the same time, I didn’t want to be tied to a certain curriculum that focused exclusively on tarab.** I wanted to learn about pop singers too! I listen to Assala, Sherine… I mean, Haifa Wehbe, one of the most iconic pop singers, got a lot of media backlash at first because she wasn’t technically trained in tarab like most musicians at the time. But that welcomed this era of Arab pop stars like Marwa, Myriam Fares, Nancy Ajram, Nicole Saba, where it became just as much about their image as their musicianship.

*A 24-tone melodic mode system, consisting of microtones, built on a scale of 7 notes.

** Loosely meaning ‘enchantment,’ tarab is a traditional artform that unfolds as a long, stirring musical performance that coaxes the audience into a state of rapture.

So it’s about honoring the old and new, for you?

Yeah, and this is something I’m exploring currently in my own music, embedding maqams into my sound as a way to preserve the culture. There’s an absence of sophisticated maqams in Arabic pop music today. I want to be able to take classical Arabic music but make it my own, as someone who grew up in London, and bridge the identities.

When was the moment you started to view yourself as a music artist, or take your singing seriously?

A few years ago, I went to a Pride of Arabia party in London and it was the first time I felt that being Arab and queer could coexist. What I loved about the community was how we were able to speak in Arabic to each other. Language is so important to me. That — as well as Pxssy Palace — was a space that made it seem more possible that there was an audience for my sound.

There was this one performance I eventually did at a Pride of Arabia show — I wanted to embrace and highlight my femininity with an outfit referencing Haifa Wehbe. I’m so inspired by her as a performer and in terms of what she stood for: freedom. She’s one of those fierce women that stood the test of time despite getting shit in the media. Absolute icon.

At the show, I opened with "Ya Tayeb" by Angham, which I used to sing to my mum when I was younger, then I followed with a muwashah —partly because that’s what I’d gone to Lebanon to learn, but partly as a way of preserving the artform. I also sang an original song that I had written, an acapella. I remember feeling so loved and so supported as an artist; people were surprised, singing along, hugging me. That’s what encouraged me to move to Egypt.

I feel like we’ve both come so far since meeting in Cairo. What were you thinking or hoping that the city would bring, when you first made the move?

I remember I’d gathered a list of people to reach out to before arriving but had no idea what I was doing at the time. I just knew that I had some songs, I wanted to meet producers — three months and then I’m out. That three months turned into two years.

How do you feel that being in Egypt has shaped your sound?

So many ways! I’ve been lucky enough to take Oud classes with Hazem Shaheen, one of the most prominent independent artists in the Arab world, and I’ve attended Sufi zar performances…. I’ve also been practicing Tagweed and Talawat (learning the maqam through Sheikhs reading the Quran). I always wanted to take this and embed it into my own music.

I’d also say being here has guided my interest in music for healing. I took up classes with Mohammed Antar, an Egyptian ney (flute) player and specialist in the maqam tuning system, where we went through each of the different maqams. The approach was also from a spiritual healing perspective: what sensation or emotion does each maqam evoke? That resonated with me. I always talk of music being very emotional, deep, raw. A lot of the songs I’ve written are about heartbreak and abandonment.

Is that where the interest in maqams stems from?

Yeah. I always say that I want my music and performances to offer an opportunity for people not to be ashamed of feeling sad, or vulnerable, or angry, and to sit with those emotions instead. To offer an optimism within music and find strength in that. I feel like in today’s world we need more of the things that ground us.

So I was drawn to the maqams because I wanted to explore how certain sounds could evoke certain emotions. I’ve been researching Arabic, Turkish and Persian maqam systems, and I’ve noticed the western twelve temperaments scale is so limited in comparison.

At the traditional music events, classes, and sessions you’ve attended in Cairo, the spaces also tend to be quite socially traditional and conservative, right?

Definitely.

What’s that been like?

What was challenging about meeting people in those spaces was that I always didn’t feel 100% comfortable or safe, but those were the spaces I needed to be in to get the musical insights I was looking for. I had to do a lot of compromising.

What’s been the biggest challenge?

I’d say financing everything has been a big limitation, as someone from a working class background. Finding funding bodies that offer support, getting into the studio…Y’all out there if you’re reading this, Venmo me!

Period! Send the dollar this way. But yeah, that can be the biggest barrier to getting things off the ground. Other than that, do you feel that Cairo lends itself well to music-making?

Yes for a lot of the experiences I mentioned above, but there are still gaps that create a struggle for artists. Spaces to perform and jam in the city are limited. It’s been hard to find other musicians to collaborate with and just make music! I love watching other musicians in action and witnessing the process of making music.

Finding the right producer to work with was also a struggle.

How come?

Most of them wanted to create this fusion of Arabic music embedded into western composition, but I wanted to highlight the maqam systems in my music and sing in Arabic. Producers I sent demos to were like, “This is great, we love your voice, we could take it in an electronic, upbeat direction….” And I’d be like, “No, I want people to cry! I want people to focus on the oud, qanun, the ney.” I didn’t want a quick, 2 minute song. That’s not what I wanted to do.

What made Ahmed Diaa [the producer of your debut single] the right fit?

With a lot of the other producers, I’d been struggling to find someone I felt comfortable and safe with, you know, where I wouldn’t need to minimize myself and could have creative control. With Ahmed, the first time we met up, we sat for a bit and chilled, and I met his fiancé, which was a nice ice breaker. It just felt really comfortable. He was very validating and positive.

Ahmed also has a sophisticated language around Arabic music and repertoire and understood the style I was going for. A lot of the producers I’d come across didn’t have the skill-set of highlighting maqams and transitions within Arabic pop music. I brought him a few tracks I’d prepared, then we narrowed it down to this track Aqd El Hob. Recording-wise, it was really smooth: he started putting chords on it, and I felt okay to tell him what I liked and didn’t like. He’s definitely someone I’d want to work with again.

Tell me more about Aqd El Hob.

I wrote Aqd El Hob (“Contract of love”) a few years ago in London. It’s about someone I was with, and things didn’t end in the best way… The song is about not being afraid of telling someone that you love them even if that feeling is or isn’t reciprocated. Being honest and vulnerable despite the outcome.

Instrumentally, I try to follow the takht. In Arabic music, the four main instruments that you perform with are the ney (flute), the qanun, the kamanja (violin), and the riq (like a tambourine) and the darabukkah (percussion). I wanted more strings than percussion on this track.

I feel like it’s a good introduction: it sets the scene for the themes I’ll be talking about in my EP, and it’s raw and concise. I wanted to write in a literal and simple way, directly from my experience without it being super cringe.

Excited for it to be released. You’ve got such a beautiful voice.

Thank you! Yeah, I’m excited to release it and see how it’ll be received, see it build an audience receptive to this sound. Also hoping it resonates with other musicians and producers for future collaborations.

On that foreign beach in Spain, El Perro Del Mar was born — the alter ego of Sarah Assbring, dark, dynamic, and a liberating enigma that has spanned over two decades. This artistic endeavor has carried her to international recognition through world tours and, as of February 16th, 2024, to her eighth studio album — Big Anonymous. However, the artist's personal odyssey, in tandem with El Perro Del Mar, might be considered an even greater feat.

Assbring exists in an industry which no longer seems to cater exclusively to her kind of venture. I prefer not to simply label her among other musicians. It's not that her craft doesn't embody music, but rather because — in an era broadening not just who can create but how creation is perceived — her sonic landscape transcends the confines of traditional music.

To make music has become an endeavor too worn, the model too depleted, cluttered with empty clickbait titles and transient TikTok tunes — appearances devoid of essence. Assbring's sound, in contrast, is essence embodied. Thus, El Perro del Mar is an artist who, like those creatives truly deserving of the title, sees no form of expression as urgent as their chosen medium. For Assbring, that medium is her soundscape.

With Big Anonymous, an album of ten tracks originally composed for a performance at Stockholm's Royal Dramatic Theatre, she extends an invitation to us. Not merely into the realm of El Perro Del Mar, nor solely into the world of Sarah Assbring, but into the depths of ourselves. Through "dialogues with the dead," reflections on morality and mortality, manifestations of guilt and grief, and searches for harmony and honesty, she hands us the keys to our own internal portal. But she won't open it for us — that task is ours alone to undertake.

How is Stockholm these days?

Really dark and cold. This winter has been mega bleak.

As all of the Scandinavian winters tend to be…

Right. But for some reason this one has been extra heavy. And schizophrenic.

I’ve been hearing about that, from my grandma. She’s the only one I’m talking to from back home. And the weather is the only thing that's happening in her life. Perhaps the winter feels extra dark this year in regards to the world?

Definitely. You wake up and it's dark outside. You open the newspaper, and suddenly it’s dark inside as well. It’s immersive.

A dark place is a good place to be anonymous, one can lurk in the shadows. Would you tell us about the name of the album – Big Anonymous – if that doesn't completely contradict the concept behind it, expose it, that is…

It’s always about intuition I think, and this title came to me immediately once I started working with the material. Once something finds its way to you so early on in the process, it usually means that it's something you should stay true to.

In regards to the theme of the album itself, it deals with a lot of abstractions — not only death, not only grief, but a plentitude of depths, and so the title is my way of trying to embody everything that goes behind it. Yet it still feels too big to comprehend or put a label on.

I read it as the fear of becoming anonymous after our own passing.

In my experience, it applies equally to the people that I’ve lost — the fact that they’re eventually becoming anonymous, which is such a terrible thing–but also, as you mentioned, when you grasp the fact that eventually death, and therefore anonymity, is coming for you, too.

At the same time, at least outspokenly, a lot of people cry out for “anonymity,” today, wishing there was a way to delete the data. Do you think that “to be anonymous” holds value?

That’s a different type of anonymity. What the album expresses is rather this endless enigma, the “nothing-but” anonymity; the fact that that’s eventually all there is. It’s about existential nothingness, really.

Which can be such a liberating force, too. I mean ask Sartre, he’s the one who told me. Have you made peace with the idea of death?

I have understood that there is no life without death, and thereby, finally, been able to acknowledge that likewise there’s no death without life.

That’s it. Pretty sure you just put the whole soundscape down in words.

The album, while being very melancholic, simultaneously puts you in such a state of relief. Kiss of Death certainly feels like a good sonic example of such — starts of hunting, terrifying, but when the presence of death finally catches up with you, it's no longer scary, it's not a stab in the back: it's a kiss. Reminiscent of how meaninglessness is being addressed in existential philosophy.

That's a nice note. Doing this album has been such an important journey for me, and Kiss of Death was really the final destination. I was coming to terms with feelings of grief and guilt and fully accepting, almost embracing, my own ceasing. I realized that I can’t change any of the things or traumas I’ve been through, however, I am fully capable of changing my perception and perspective of them.

I have this mark on me, now I choose to see it as something beautiful. I can choose the stance of having loved and having felt love for the people that are now gone. And me remembering them is also proof of love. It boils down to perception–possibly cultural values as well–and rethinking requires that we let go of our fear. We should aim to be brave enough to question what events should be attached to what emotions.

How did you let go of your fear?

Writing this album provided me with a tool, something to carve with. I think of it as poetry, and it’s been a healing process; a way to understand myself on a spectrum I haven’t quite dared to explore before. Until I wrote this album, that is.

On a non-conventional level? It takes some, several detours to realize that even language — what we use to understand our selves — are just generalizations, thus to go deep we need to go beyond words.

That goes for how we’re told to treat or react to death as well. I can only truly speak of the Western, Scandinavian perspective, where we really have furthered ourselves from the idea of death. That creates some tangled agonies, some of which probably won’t come back to haunt you until later in life, which seems fine, but later, once they do, we’re not sure what they are or how to deal with them. It’s weird. But that's what and why I want to talk about–what I would like this album to navigate through–emotions of grief, guilt.

That’s a therapeutic approach: the methods of sound. Sound transcends words, and therefore puts us in closer contact with truth, at least according to Nietzsche, or perhaps I’m just damaged by professor Dodd. But let’s talk about guilt for a second, I read that you felt guilty for being alive while others aren’t?

I did. But then I finally asked myself the right questions, even though they came at the wrong time. By writing these “constructed dialogues”, the lyrics, I was able to transcend into a place of being forgiven. It's very frightening to be vulnerable, but once you reach a certain point where you start dreaming about things, having nightmares, waking up to the feeling of being haunted, then you have to deal with what might have felt impossible at first.

I’m not trying to make it sound easy, I mean it's very frightening to be vulnerable, but once you reach a certain point where you start dreaming about things, having nightmares, waking up to the feeling of being haunted, then you have to deal with what might have felt impossible at first.

Looking outside of yourself can really help as well. I mean everybody has, or has had, experiences with “darker,” feelings, whatever that really implies. What I find interesting is how we so rarely touch upon them, it’s like we’re all so afraid that we’re going to bring up bad memories,

“Weigh down the mood?”

— exactly. And so we stop talking about them, pretending like they don’t exist, arguing that “the word is already so heavy,” without realizing that when we suppress these emotions we’re actually adding weight, as opposed to once we dare to talk about them, that's when weight is released. It's almost illogical. But I believe that it’s important to keep asking questions without finding a definite answer.

In short, it's been a very personal intimate journey, but at the same time, it's also been a very social, bonding, experience.

What about that experience? Tell us about what it was like to create music for a performative setting like Dramaten [The Royal Dramatic Theater].

I was freely commissioned, permitted to do whatever I wanted to, and it certainly felt like the right time, and the absolut perfect place. Dramated being a stage for spoken drama, I approached the project as a performance rather than “I’m going to make an album and put on a concert.” So performance became the starting point, which is obviously very different from how I usually create, this allowed the music to go places it never could have reached if it weren't for the idea of stage.

In the studio it's just the microphone and you, what's the main ingredient when you compose for a performance?

Movement, sound, choreography, lyrics–I’m pretty sure I had all of these factors equally considered in my mind, which probably sounds chaotic, but it wasn’t. I felt like I found a very natural place which allowed me to be filterless; the dancers, the stage and the design removed the pressure of me as the vocal point, which made it that much easier. I could be 100% personal and still make it nonpersonal.

The commission opened a different door to what felt like endless opportunities, but I think of the album that came out of it as a very separate thing. The performance was a performance, and the album is an entity in itself, it’s not stage music, even though they’re both rather melancholic.

What about it?

Well, I'm very drawn to melancholy. I think it is a big part of me, always has been, and is always going to be. The type of melancholy that does not leave you feeling low, but leaves you feeling thankful, blessed about having feelings, just emotionally richer. That’s the ambition of the album; to embrace the emotions of life. Saying that out loud makes it sound cheesy…

The quote in itself sounds corny, indeed, but once put in relation to your tracks it becomes something completely different. I think when people want to celebrate life they usually plug in, I don't know, Stayin’ Alive with Bee Gees?

That’s just me. I would never, ever, cheer myself up with “happy music.” It just doesn't work. It's what it is. I'm the kind of person who prefers to watch a horror movie instead of a comedy to make myself feel better.

Because on some level the horror feels more honest?

Because I like to be shaken up a little. Every now and then I tend to go too much, and perhaps too far, into the darkness of existence, and then the horror is a great way for me to wake myself up, to realize “what the fuck! you have this beautiful life, and it's right in front of you, and it's happening right now... and eventually it is going to come to an end, even for you, my dear…”

Better get out there and celebrate. Are you a believer in the afterlife?

I am not.

What about the film, you’ve been in music since 03 but this is your debut in terms of working with visuals, does it function as an extension of the Dramaten performance? The performance-the album-the film: the non religious holy trinity?

My desire to film goes way back, but the performance in 2019 opened the door, then it slowly progressed from there. I work closely with my stylist, who's also an art director, Nicole Walker, she also played a key role at Dramaten. Once the performance was done and the album recorded, she and I discussed what it would be like to push the project further, it got us both excited about doing a film. A movie felt like the right medium, and she sure is the right partner – the one you don't have to say more than a few words to, for she already understands your vision.

We wanted to find a way to make the viewers uncomfortable, to go places one usually avoids, consciously put pressure on where it hurts. And to me, doing that means going via horror.

I don't feel like you’re the type of artist who sends people off to the uncomfortable for the sake of being uncomfortable, but rather “I want you to discover something of yourself, please go dwell in this feeling and see where it brings you.”

Exactly. It's not for the entertainment of being horrific. The movie is supposed to be an equally therapeutic experience.

You mentioned earlier that you carry this mark on you, whereas in the film, one of my favorite sequences is when we see you biting yourself in the arm, again and again — is there any chance these two have a resemblance?

Exactly, that's the mark. It symbolizes one of my most vivid childhood memories. I was at a funeral, probably my first one ever, around five-six years old, finding it so difficult when looking at all of the adults around me who were really holding it together in order to not cry. It was such a bizarre scene to my childhood eyes. I remember finding their behavior so strange and foreign, but still I did the same – I swallowed my tears and left feeling affectionate and sincerely sad. My first reaction to keep it together that day was to bite myself in the arm. I did so almost unconsciously, but it stopped the tears.

Today, I view the mark as a symbolic translation of our modern day -disease, the result of an innocent child’s behavior who naively adopts the pattern of her surroundings, while our social environment leaves us feeling rather numb. It's no longer common to give ourselves time for grief, we diminish our minds – it's a scary path.

One that we can wake up from if we dare to acknowledge its existence? If so, I’m planning on dwelling in it, on 28th of March, at ca 8PM, on 233 Butler Street, New York, to be exact.

It’s going to be so special to see people perceive the album live. Maybe we can meet up when I'm in New York.

Tickets on you? Red wine on me.