Stay informed on our latest news!

Sign up for our newsletter

Focusing on the connectivity of history through realism, 'PAST is PRESENT is FUTURE' powerfully articulates the disposition of energy in time. While the multi-medium artist has carved out his visual language, he has adjoined written pieces of work within this exhibition that further contribute to this preservation of time in history. Dr. Virginia-Lee Webb is a scholar, writer, and curator who has contributed Oceanic and African sculptors and masks from a significant private CT collection. This addition of historical artifacts provides greater context to the exhibition's narrative. 'PAST is PRESENT is FUTURE' explores the web of connections that make up the cosmos. Lance De Los Reyes states "I have learned that anything a human thinks about, says, or acts upon operates much like a boomerang. If you throw it into the universe, the energies of what people think about, say, and do may possibly manifest, becoming karmic boomerangs that return tenfold."

New Gallery, La Fonda, Brings Emerging Art to France’s Coolest Coastal Town of Biarritz

Centering around themes of desire, consumption and the body, the season featured three showcases: paintings and sculptures by Hanna Rochereau, photography by duo Chaumont-Zaerpour (Agathe Zaerpour and Philippine Chaumont) and a series of short films by director and editor Lucia Martinez Garcia.

“The art scene in Biarritz is definitely growing, and we're thrilled to be part of it,” continues Christie. “The town’s blend of historic charm and tourist appeal makes it a perfect place for this kind of project. We’re using our international experience to meet the rising demand for diverse cultural offerings. We’re planning for both busy times and quieter moments to keep things balanced and interesting.”

Read on as office’s Paris and Biarritz-based Editor-At-Large Paige Silveria has a brief chat with everyone.

Paige Silveria— Tell me about the show, "Everything Not Saved Will Be Lost." It looks like it was intentionally created for the gallery space.

Hanna Rochereau— I’ve always wanted to make a show that adapts to a specific space and this was the first time I was really able to do it. I’ve been able to plan and work on it for about a year. This gallery is so interesting — it really allowed me to create a concept that was theatrical, something that’s not very easy to do within a white cube. It was really important for me to fit into the space, especially when considering the color and the materials I chose. For instance, all of the frames I made myself to match the existing framing on the walls.

PS— Can you give me more background on your organizing concept?

HR— I intentionally create a kind of tension between what is visible and what is hidden, which ties into the exhibition title. The idea is about reversing roles, where the display itself becomes the object presented as luxury, while the "purchasable" object disappears. I’m super interested in window displays, behind-the-scenes storage areas, the framing that is created for the products, the boxes and wrapping. My work is all about desire and desiring objects, and the frameworks that help to create that desire in the consumer. I love to play with what is missing in the space and shift the focus to these frameworks. A lot of my paintings are linked to the fashion world. There will be several collections each year, so quickly, and so much consumption is generated. So while my subject is all about this fast-paced world, for me as a painter, my process is very slow — digesting the concept and creating the artworks.

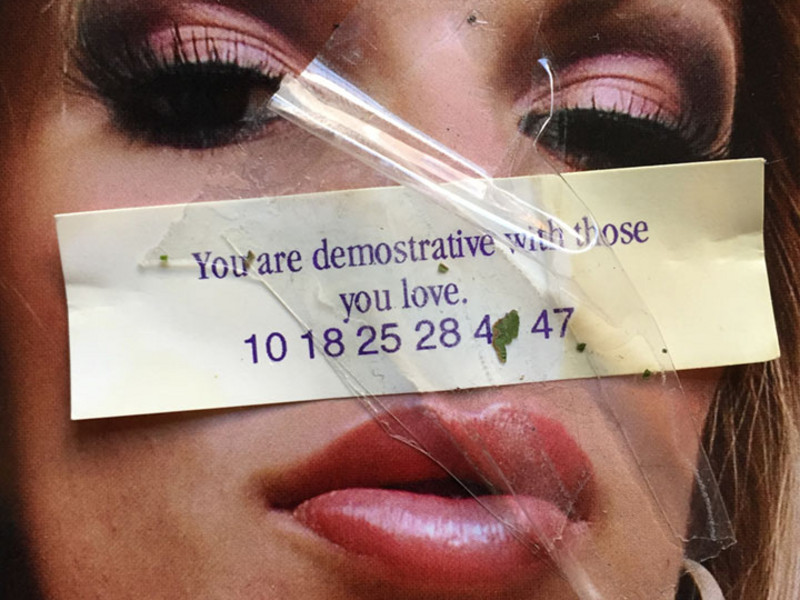

Paige Silveria— Tell me about creating your exhibition, “Points of Sale.”

Chaumont-Zaerpour (Agathe Zaerpour and Philippine Chaumont)— When Marie and Christie suggested we do an exhibition in that space, we immediately thought of a project that would engage with the architecture. It's a very bourgeois environment, and we thought it would be interesting to display something reminiscent of a boutique, but in an irreverent way. Recently we've been very interested in exploring the imprint of fashion imagery on our intimate relationship to clothing. The construction of fashion images relies on a set of codes, the mastery of which keeps those who create them in an illusion of superiority, while ignorance of these codes excludes the intended audience.

In “Points of Sale,” we cropped and enlarged pretty brutally some archives from our editorial and commercial projects, to form a naive and linear inventory of anonymous feet displaying their shoes. We wanted to reduce the status of the photographs from which they are extracted to their essential advertising triviality. Arranged in a continuous line, they highlight the perpetual metamorphosis: these codes that we create and that, in turn, transform us. The images themselves have a dusty feeling from being re-photographed, enlarging the print raster of the magazine they come from or the grain of the film. They are printed on a very thin and yellowish paper that feels like big pieces of old newspaper, hung on the walls with tiny pieces of paper tape: when the high windows are open, they float like spirits haunting the place.

PS— What kinds of projects do you love to do and why?

CZ— We have a great time working on both our commercial and artistic projects. We always worked in a way where both are really connected. Recently we've made much more space for our personal work, and it often is a comment on our work as fashion photographers. So each part really nourishes the other. A lot of our images start from references to the history of photography and its acceptance as an artistic medium. We've also always felt very drawn to vintage fashion imagery, and earlier aesthetic codes in general, iconic advertising campaigns, women’s magazines from the 60s, 70s, 80s and to classic photography. We try to use the language of fetishism that underlies these references and to subvert it to the point of absurdity. Having studied graphic design and worked in the publishing world before photography, we attach a great deal of importance to the relationship between images and the resulting narrative. The final form of our images is most times a layout or a sequence, and we have a hard time considering each image on its own. So we love storyboarding our stories meticulously: we usually draw each spread we're going to shoot, and determine in advance where each image will be in the layout. So we're quite organized when we shoot. We usually get more experimental in the editing process. And being the two of us makes every part of the process really exciting. It's so helpful bouncing ideas together, and so reassuring to be able to navigate that industry being around your best friend at all times.

Paige Silveria— The films that were screened with La Fonda were absolutely heartbreaking. Can you explain the recurring focus and themes throughout your work?

Lucia Martinez Garcia— I’m interested in portraits, particularly of women. When a person transmits emotions to me, I want to film them and showcase their beauty and fragility. I like to make films infused with both poetry and violence. My characters are often filmed at stages of their lives where they’re lost, searching for themselves; where they are vulnerable and, at the same time, we perceive their strength and dignity. I try to capture the unspeakable.

PS— What's the process like of locating, casting and working with non-professional actors? Why do you prefer to hire with them?

LMG— Apart from my last film “Blue Light,” I wrote all my projects knowing who the actor was going to be. I draw inspiration from their personalities, from the experiences of those around me, and I stage it in situations that I imagine. For "Blue Light", it's different, because I wanted to experiment with other things: 16MM, having a person I don't know play, creating narration without words, etc. For “I’m the only one I wanna see,” [described as “A woman, a dancer, a creature, dances, free. She laughs at the violence, the insults, the looks that reign around her."] even if the film is not inspired by the actress, I knew her way of dancing and the abilities she had. She’s a very good friend, Léo Chalié, who played in my first films, and she became an actress afterwards. Now she plays in series and feature films, but I know she always wants to experiment with new things, and with this film, it was an opportunity to do so.

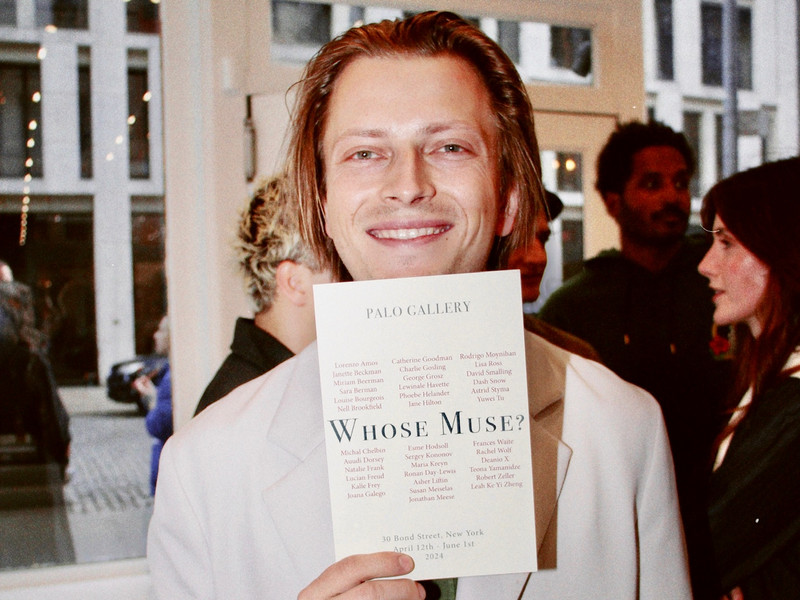

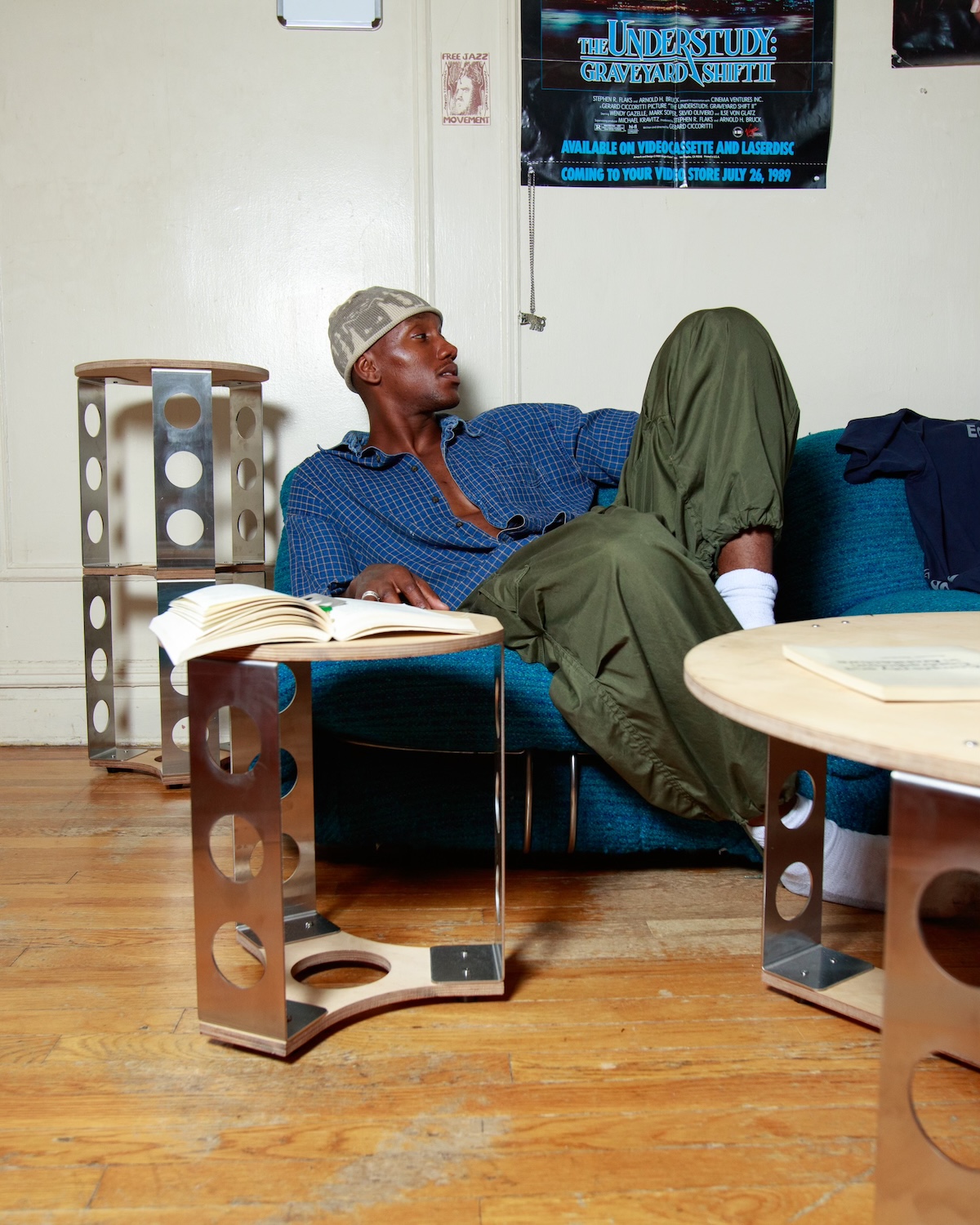

For Emmanuel Popoteur, the Future of Furniture is Modular

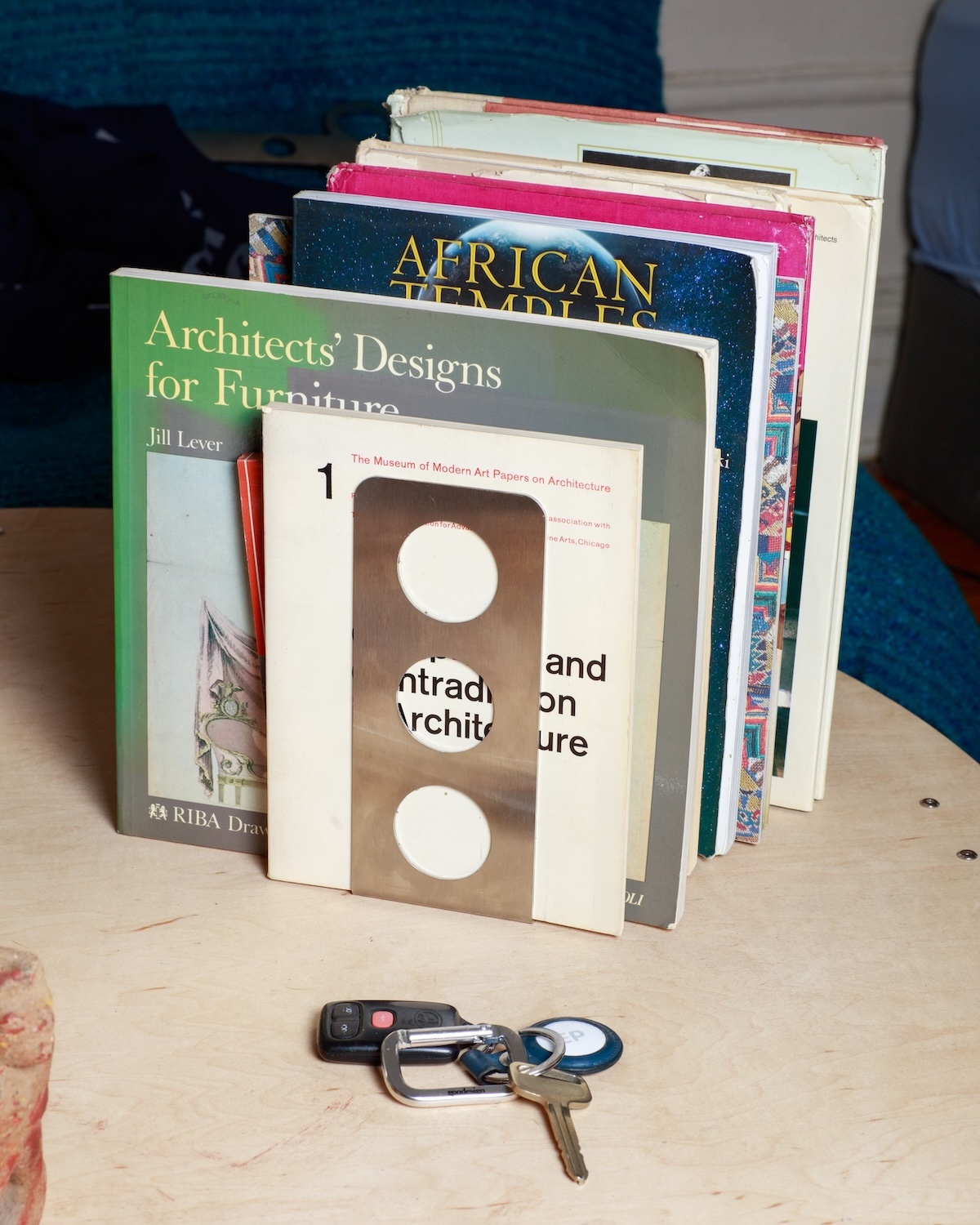

Popoteur debuted the Eclipse System at goodesign’s inaugural event at Awake's LES storefront, showcasing the set's versatility by building stools, coffee tables, dining tables, and even clothing hangers. The space also featured a curated collection of books by Storagebased, while a Christian Tokyo DJ set and Solomon Gottfried’s jazz quintet performed atop various pieces of goodesign furniture. For Popoteur, a Washington Heights native known for his innovative spirit, the event marked a significant milestone. He first made waves in the furniture world with his PVC pipe-constructed chair, which not only caught attention but also set the tone for his creative ethos: making the extraordinary from the ordinary — a philosophy that's clearly embedded in the DNA of the Eclipse System.

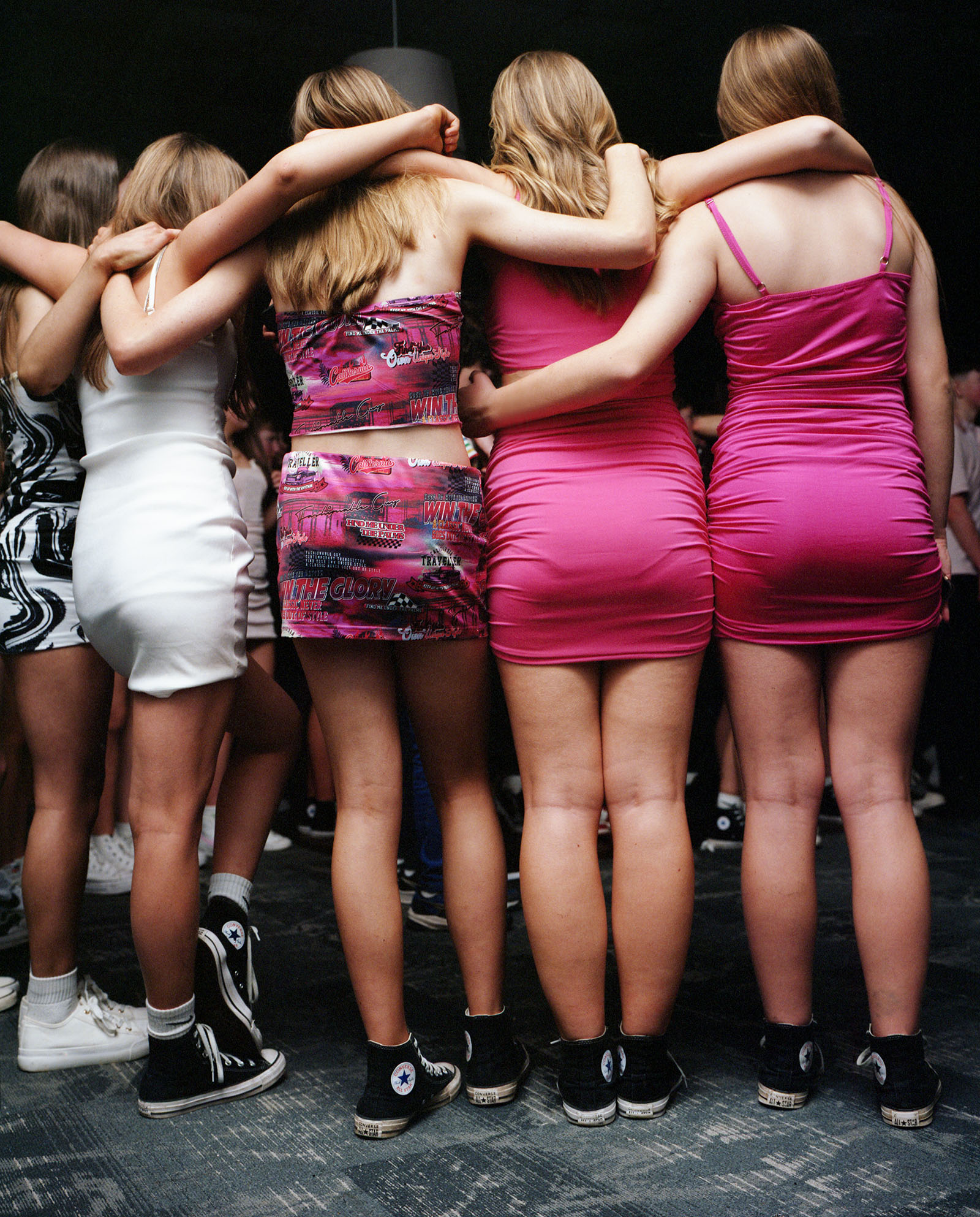

Girls' Night Through Eimear Lynch’s Eyes

When I spoke to Lynch, she had just moved to Brighton, England, seeking a balance between city life and the ‘nothingness’ she experienced growing up in Ireland. We talk about the return of cheap bodycon dresses, Trainspotting, and erasing boys from the frame. Read our conversation below.

Julia Silverberg— When I was looking through the images you sent over from Girls' Night, one stood out: there was a girl wearing fishnet sleeves with her jacket tied around her waist.

Eimear Lynch— When I took that image, I knew I was caputuring something rare. At these events, everyone tends to dress the same, but that girl stood out even though some of her friends had similar outfits. She looked amazing and had such a sweet demeanor, just quietly observing the party. I met her at one of the discos where everyone was only 13 or 14, so it was probably her first time at a party like that. She and her friends were cooler and happier than the rest, and in that portrait, she just seemed so content with herself.

Did you notice ways in which the girls who were wearing the disco "uniform" still managed to assert their individuality?

Honestly, I feel like they didn't have any takes on the look — if they were wearing the bodycon dress, they were wearing the bodycon dress. I was the same at that age; it wasn't until I got a bit older that I started experimenting with my hair and clothes. During my first year of going to discos, I just wore the standard dress from ASOS, but I think it’s a rite of passage. At that age, I wasn’t thinking about looking cool, I just wanted to finally be a woman and wear the dress.

It’s funny because I still have this H&M dress from my first teen party. Sometimes I try to find a way to style it now and make it cool again.

They’re kind of making a comeback! Some of the colors are amazing, but the material of those cheap dresses is so shit. Back then, my friends and I also all wore these really ugly heels that we couldn’t walk or dance in, but now, teenagers are smarter. You still see some of the same looks, but the girls are all wearing trainers — Nike Air Maxes and Converse are the big ones.

Do you think your book challenges the idea of getting ready as an overly feminine ritual?

In an ideal world, there wouldn’t be any beauty standards or pressure to wear makeup and do your hair. But since they exist in a patriarchal society, I want to celebrate the good that can come from them. The hours spent getting ready are so fun, and boys don’t usually get to experience that. There are benefits from the pressures on us, and that’s something to be celebrated.

You often work around female identity in this way.

I’m still quite new in my career and doing a lot of self-reflection; that’s why I’m focusing on girlhood and the experience of being a girl. Maybe once I feel like I’ve fully explored that, I’ll move on to something else, but for now, I want to delve into what I know and understand. At this point, looking at my own life and upbringing through my work is a lot more authentic for me.

Did you learn anything specifically about femininity from your work on Girls' Night?

The book really reminded me of how important female friends are, and how essential it is to have a good group of people around you. I think girls can get a bad rep for being bitchy, but the ones that I photograph are all so lovely to each other. This new generation is really aware of mental health whereas when I was a teenager, people didn't realize that being mean was a bad thing. Now, people are a lot more supportive of each other, which I think is amazing. Also, when I was in some of the girls’ bedrooms, they would talk about boys, but they wouldn't talk about them as if they were chasing after them. They were talking like, if I kiss this guy, it happens, whatever. They weren't obsessing over them, which I found really interesting and different from when I was their age. They seemed like they had the control.

How did you manage to capture such vulnerability in your work? None of the images feel performative.

Some of the girls were a bit harder to get to relax, but most of them forgot I was there pretty quickly. The people in the photos were real groups of friends meeting up after school; I was just an addition to their night out. Sometimes we’d chat while they were getting ready, but most of the time, I’d say, “pretend I’m not here”, and then I’d snap away. They don’t get to hang out much because they’re in school all the time, so they were busy catching up with each other. At the clubs, I’d do laps to make sure everyone saw me, smiling, and trying to look welcoming. During the first hour, people were usually too on edge for photos, but once they got used to me, I could capture those more intimate moments.

Do you think the backdrop of the current economic crisis influences how we romanticize those moments from our youth?

Nostalgia is always a powerful feeling, and it’s something that resonates with me in other people’s work — it’s an important part of art and films. With my project, teenage girls haven’t been documented solely like this before, and that’s what resonates with people. There’s this view of youth culture, especially boyhood, in a Trainspotting way, where boys are being bold and running around. Because of this, I wanted to show that girlhood has its own exciting aspects. I tried to create a realistic look at growing up as a girl in Ireland, and those feelings of transition connect with everyone. Your photography captures that tension between the carefree aspects of our teen years and the approaching realities of adulthood. That transition is really apparent in the awkwardness of the girls’ poses and stances. In my photos, they seem unaware of the impending weight of becoming a woman. They’re so confident while getting ready and heading to the discos, but once there, they’re so insecure.

My friends and I were so eager to be older at that age.

It’s fun to be excited about getting older — why not? At 13, 14, 15, going out is the best thing ever. It’s when you’re 16 or 17 that things get more complicated, going out isn’t the same, and you become very conscious of how you look. The younger girls, though, are wearing a dress and makeup for the first time, so they just think they look amazing.

I also noticed you cut the boys out of the picture. Why?

When I was a teenager, the only bad experiences I had were because of boys. A lot of my insecurities stemmed from them being mean; I never had those issues with my girlfriends. I was always a confident kid, but around 16, boys really broke me, and left me with a bad feeling about that age. Because of that, I wanted to focus on the good parts of my teenage years — picking out dresses, doing hair and makeup with my girls — and cut the boys out.

I like this idea of reclaiming your own teen years. Do you think that makes the book an idealization of that time?

It’s definitely not a factual documentation since the boys aren’t included. Maybe one day I’ll go back and do a version of the book highlighting them, because there are interesting stories to be told there too.

The project is so clearly specific to you, especially with it being set in local churches and community centers around Ireland. How did these locations influence the narrative of the book?

Going into the project, I thought there’d be big differences between the venues I shot, but most of them looked the same, especially with the lighting. It was also always funny to see people arriving and leaving at the discos, especially in the middle of nowhere in the countryside — no one wore a jacket! They’d wear their dresses, and their parents would drop them off and pick them up. Surprisingly, this energy was quite uniform all around Ireland.

Do you remember where your teenage disco took place?

I went to a venue called Wes in Dublin, but sadly it’s closed down now because I’d love to go back. It was in an old rugby club, and I remember it being so sticky. The walls were sweaty, and at the end of the night, we’d push each other against them, and they’d be full of condensation.

I feel like that's what someone thinks of when you say “teen discos”, it’s…

Very grimy.

How do you think the themes of Girls Night will be perceived by future generations?

I hope the images will always be relevant, and want people to connect with them in the coming years. I’m surprised by how similar everything I captured is to when I was going to discos 15 years ago, but I do think the uniformity will stop. People will start to be more stylish and wear their own things. You can already see the push towards taking more risks, like wearing funky eyeshadows and lipsticks. I never did that when I was younger, but people are learning more from TikTok and Instagram.

Maybe if you redo this project in 15 years, you’ll get a completely different outcome.

Yeah, hopefully. I want younger people to look at the book and think it’s crazy that everyone used to wear the same outfit.