Emann Odufu: It took me a while to process the exhibition. I was initially overwhelmed by that level of detail. I was at the exhibition in the installation space with some friends, and we heard a humming noise coming from a box. It took us a second to realize that the box was a refrigerator. We opened it up, and there were apples in the fridge.

It wasn't until I started to look at Miss Understand as a character that I began to see her not as a representation of you solely as an artist but as a holistic representation of femininity in the modern world that I began to wrap my head around the exhibition. Miss Understand felt like a play on Miss Universe and every woman. My first question is for you, the artist, who is Miss Understand?

Oda Jaune: I’m so happy that you opened the door of the refrigerator. When I was working on the installation, I loved to imagine the viewer to experience the exhibition with their eyes and hands and to lie down on the bed, sit on the chairs, discover the overpainted books, and spend time in the space so they become part of the installation themselves.

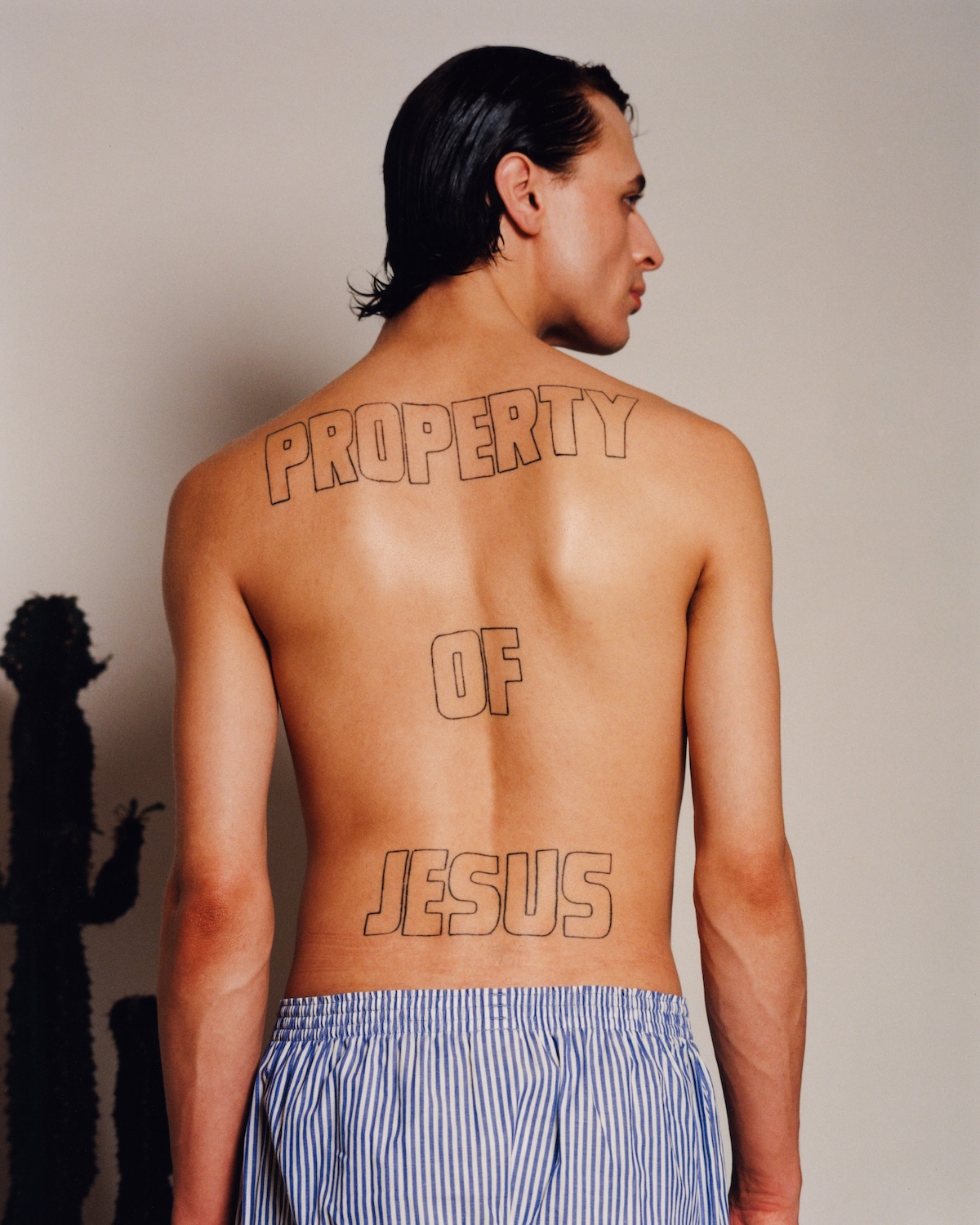

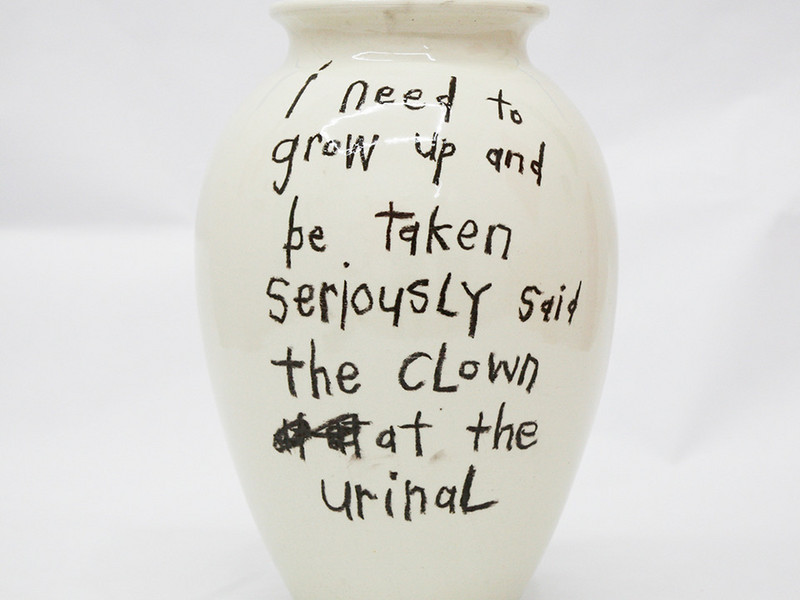

“Miss Understand” is not a particular woman. It is not me. It is no woman and at the same time maybe every woman. It’s also for everybody who feels like a woman. I came up with the title on a walk with my daughter. We were looking at people's T-shirts because there was often a slogan written on them. She asked me if I had to design a t-shirt with only text, what would it be. The first thing that came to my mind was “Miss Understand” and I said that I would divide the word into two.

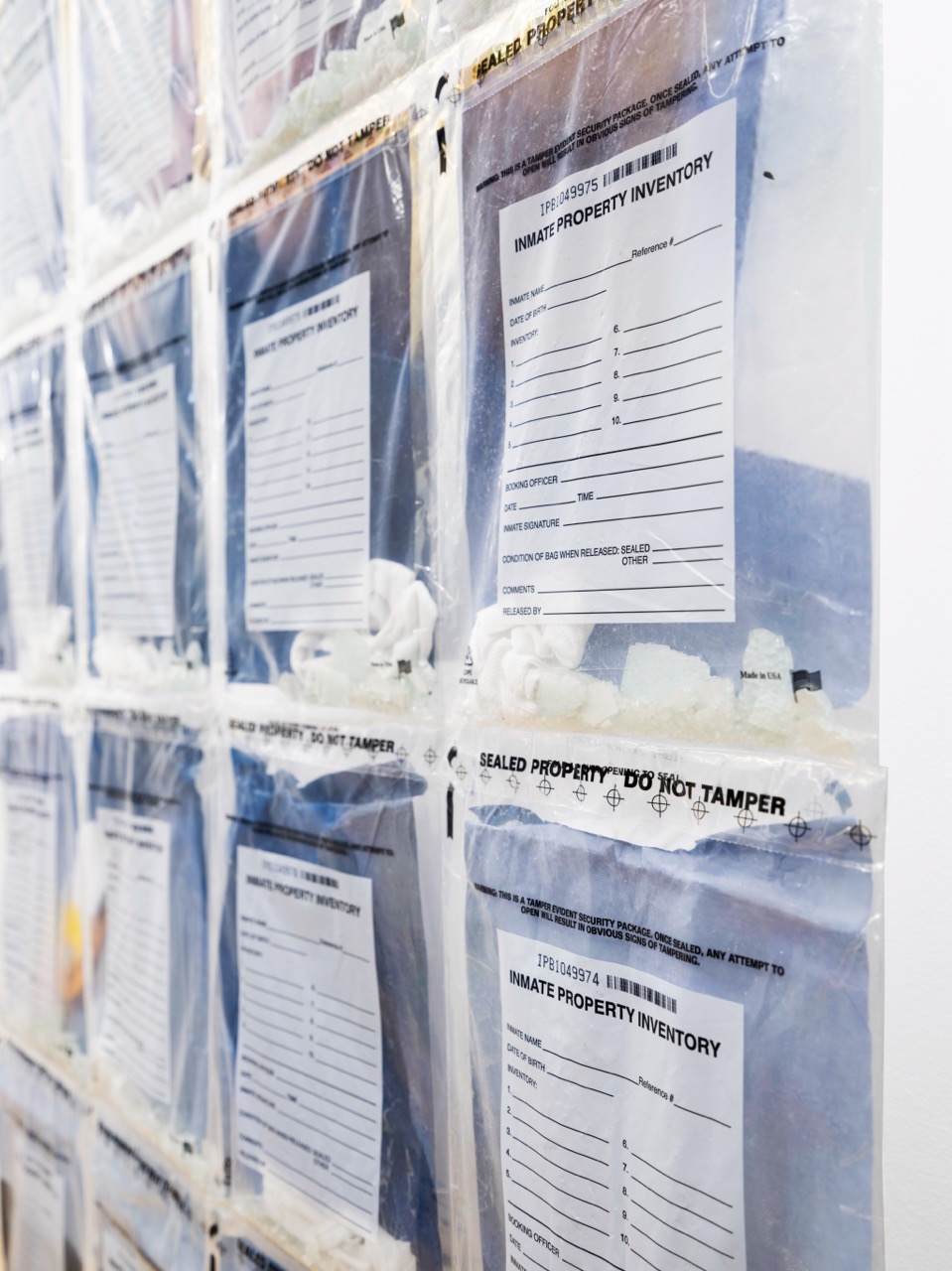

It's something in the nature of the woman that it is impossible to be understood. Extending it further, I think it’s in the nature of a human to not to be understood. How absurd is it to me that we are living in a time of so many numbers, facts, algorithms and scientific proofs that bring us further away from (our) nature. We're forgetting about magic and things that are not so easy to understand. When you have the feeling and understand something, you put it in a box, label it and maybe you get a key and close the file forever and say “Oh, this is this way” and you are limiting yourself. I feel almost allergic to the idea of labeling the world, people, history, everything that we try to put in a box.

Within the work there may be questions for the viewer, for their answers to arise but they don't need to position themselves and don't need to judge. Our world is so polarized. You must choose left or right, for or against, which constantly puts us in separation and division. How about making it more open for us to make mistakes and for misunderstandings and more freedom?

EO: I think that that makes a lot of sense. I saw that throughout the show, there's this idea of subverting duality or this idea that in the process of misunderstanding, there's this sort of mystery that is confronted and acknowledged. As the viewer, you see the exhibition and try to make sense of it all, but try as you may, you won't see it from the vantage point of you, the artist, and It's almost futile to try to understand.

I want to talk about the performance art piece happening on the show's last day, which I'm excited to see, and where you will animate Miss Understand in a personified form. As an artist, I love that you dig into the multidisciplinary aspect of your practice and constantly push the limitations of how you engage with your audience. I read that in the last show at Templon in Paris, you had a hologram of the Tree of Life, and now you're activating this current exhibition through performance art. Can you talk about how you're constantly reinventing your practice and your approach to toggling between these various mediums as you engage your audience?

OJ: I love that you found information and the little journey that I had with the hologram. I loved it because it was the pandemic, and the real situation where we could reset individually and as a society. I was asking existential questions, and I thought about how we're living in a world that is, for me, even though it's so dominated by inventions of our time, it is still quite magical. It's almost like another reality within our reality. I was working on this show during covid lockdown thinking about how there’s something invisible you couldn't see, you know it's in the air. I found it fascinating that we were in such a frenzy over something invisible and how it could, for a moment, change everything in our world. This thought process around visible and invisible, tangible and translucent, leads to an interest in holograms. The more I researched, I understood that I would have to create my own technique for creating a hologram, because the best things happen when you have a limited budget.

I said “OK, let's think about what we can do if we improvise.” So we created something, and it actually worked. It was like magic because we didn't have much, and it was such an improvisation and the people who loved it from all age groups were touched by it. For me, it's about how real I can make an idea and what techniques permit me to execute those visions.

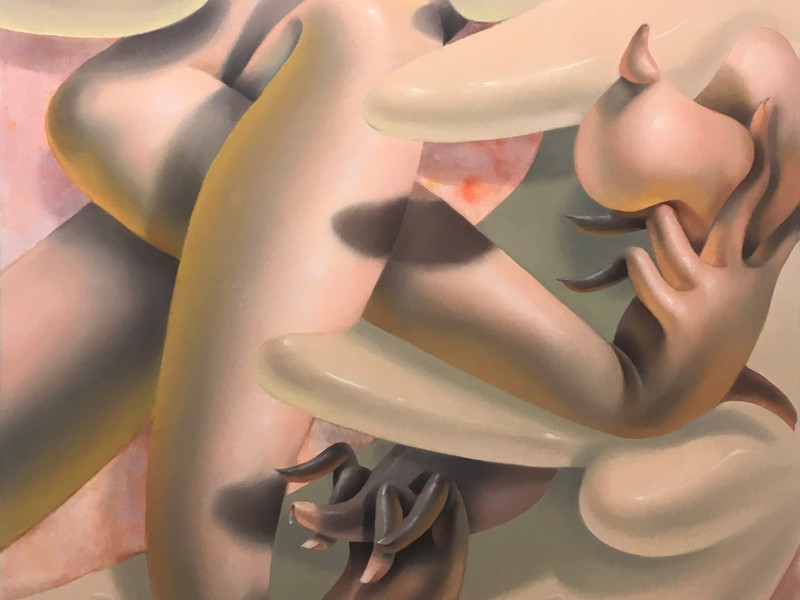

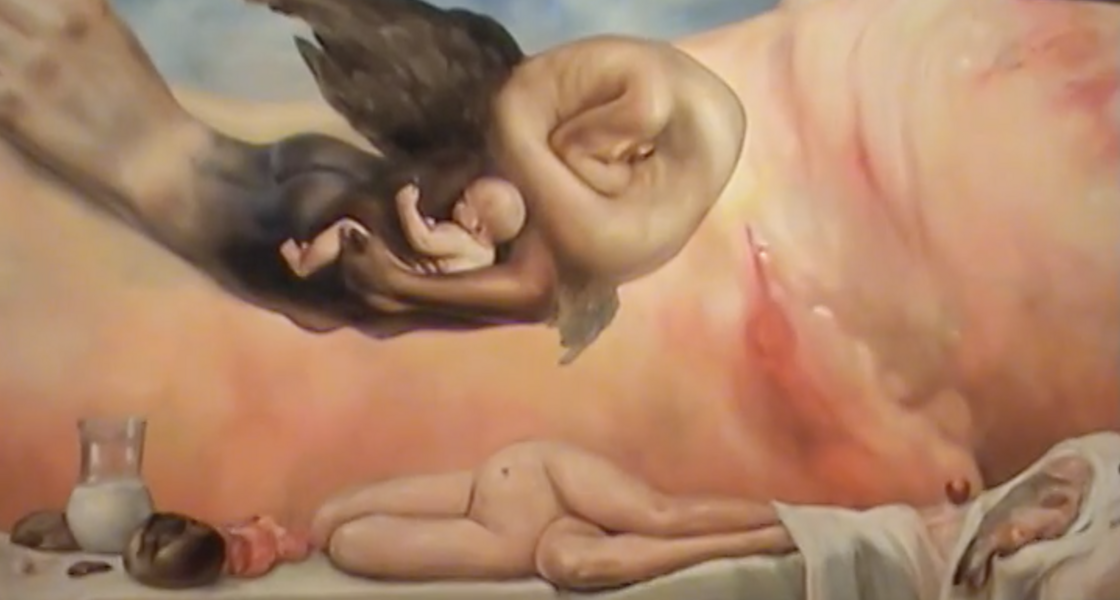

I was trained as a painter and when I was younger, I really loved observing the human body. I thought it's just so incredible. Humans in general. I really love nature and observing the light and the shadow and how everything changes constantly. I honestly don't remember a moment in my life when I have been bored. What a stunning experience it is having eyes. Painting oil on canvas is the closest I can come to what I have as a vision. At some point, I reached a stage where I can paint everything that I imagine, so I created sculpture to see how I would feel when my ideas become three dimensional. When I was a young girl, I loved working with clay, the softness of it. I was also intrigued by wood and stone, marble but then I was told that, because I was a woman, I would only be able to work on small things because physically I would never be able to do what men can. I accepted that and focused on painting. Because I wanted to be as free as possible as an artist and I do love painting in an unconventional way, but I didn’t stop loving sculptures, so later I reapproached sculpture again.

One day, my daughter asked me if I wasn’t a painter what I would do in my next life. I realized that I would love to do movies, but I want to do movies that I only need to do myself. That's why there are six short videos in the exhibition and I loved making them.