Last Days in a Lovely Place

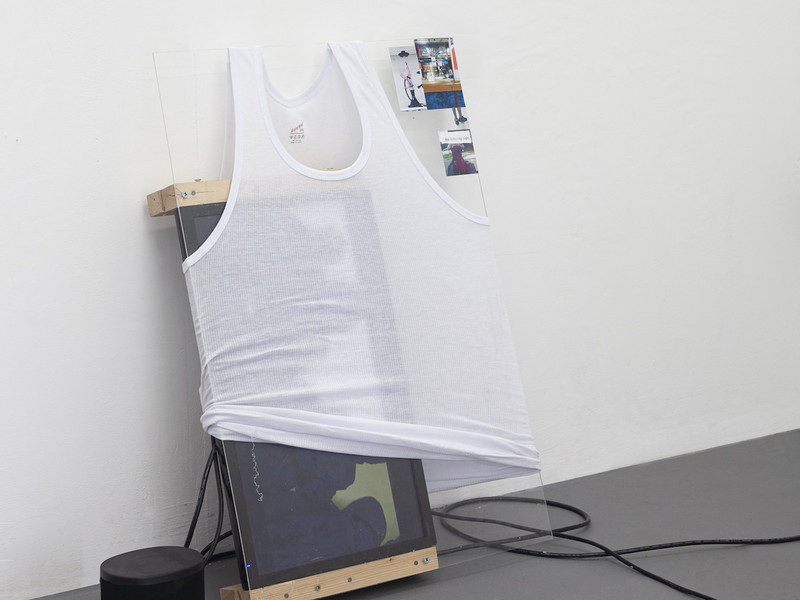

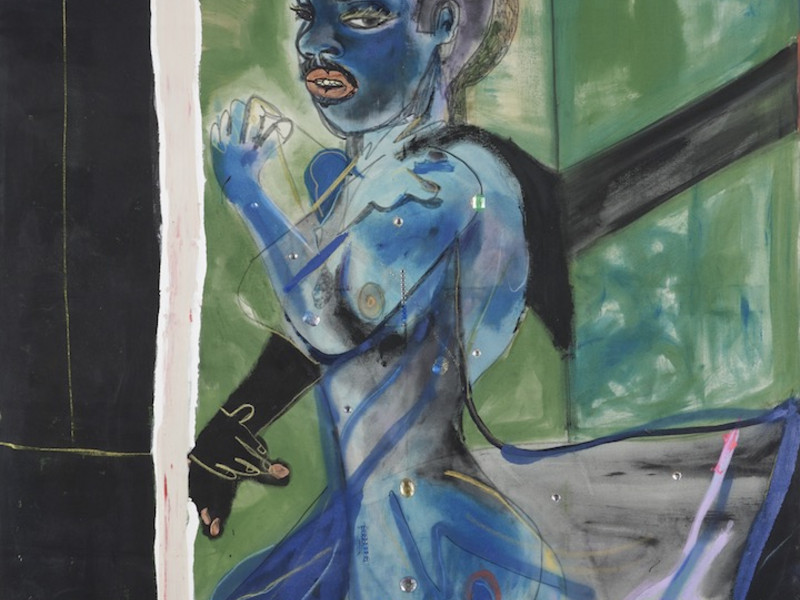

Prints and photographs line the walls, while the showstopper is a rail-mounted 4K monitor leaning against a corner, oriented upright. This orientation, a position becoming increasingly familiar in video art and installation, mimics Darst’s iPhone, the only tool he used to realize this video and the three nearby prints. Sacrificing “professional” tools in favor of the mobile-friendly, Darst moved from app to app to hand draw the over 3,000 frames and nearly three minutes of Mt. Sinai Institute as well as the nearby squiggly dye and aluminum prints One Flight Up, Mental Connecticut, and How Relaxed.

This mobile production clearly read with some now-eye roll inducing words circulating in contemporary criticism—artists working in “post-studio practices” while existing in the perpetual citizenship twilight of the “post-tourist,” itinerantly bouncing from biennial to biennial, sublet to sublet. However, Darst presents these concepts in the most banal way. The aluminum prints were designed on his phone during his commutes. This is hardly globetrotting glamour, this is the worker-as-flâneur, bound to the city and its schedules. Here, the artist-as-user is the post-Situationist freelancer creating their work in a subway fugue.

Of course, in rejecting, or not even acknowledging the studio, Darst unpacks a further tension in his practice—that is with the mythic individual genius of the abstract expressionist painters, famous for canvases strewn across the floor and unstretched on the walls begging for gesture, for real, material paint splattered and poured. But, after all, it’s 2018 and all anyone really does is gesture at clean surfaces in hopes of making images—and no one even has to get dirty.

Darst’s revised abstract expressionism expresses the character of the surface, that is, the screen, and our simultaneous distance from and intimacy with it. Finger marks scrub across the the monitor of Mt. Sinai Institute and the aluminum surfaces of the nearby print-paintings, figuring the presence and necessity of the hand in its visual absence. Each brushstroke mirrors the size and shape of the finger that makes it, each swipe is indelibly of the hand and body as it becomes digitally coerced into the immaterial flatness of the screen. Darst reconsiders what it means to make by hand, cogently indexing the manual nature of technological manipulation, the dual—here, overlapping—meanings of “digital,” so forgotten as we disembody ourselves in our technophilic imaginations.

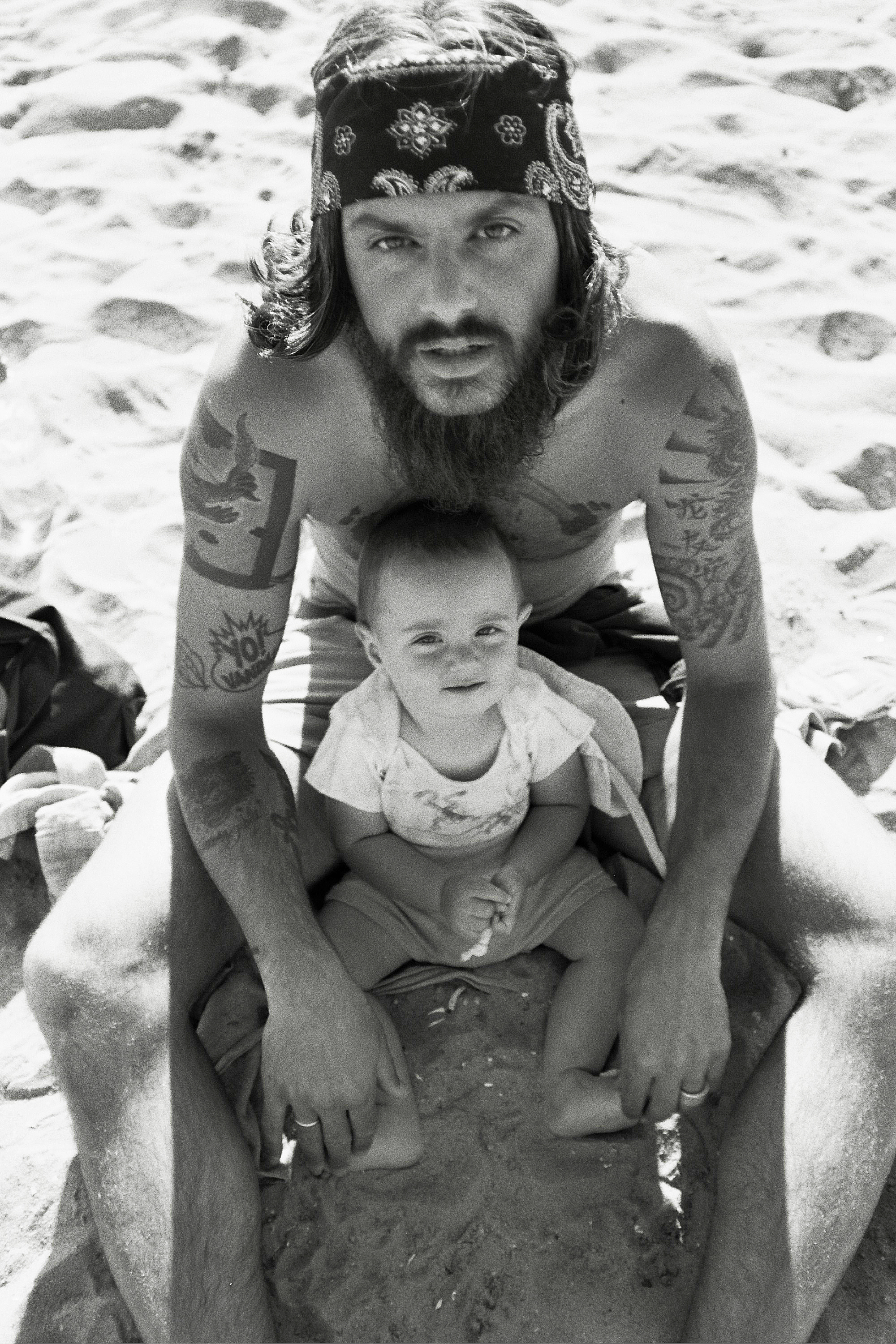

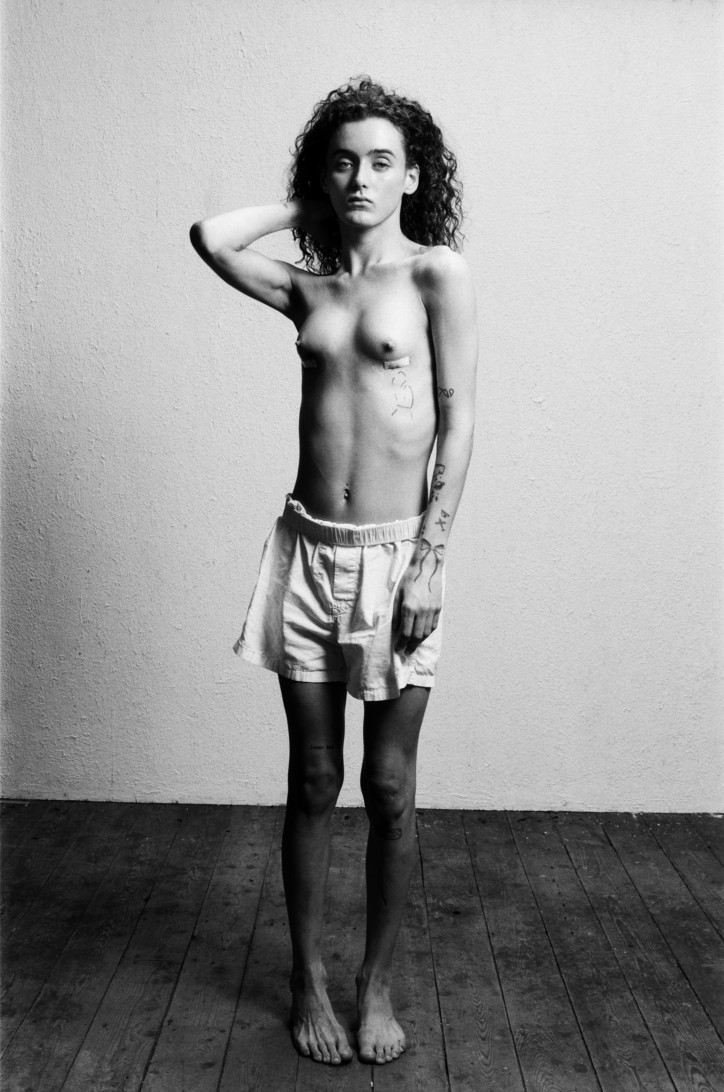

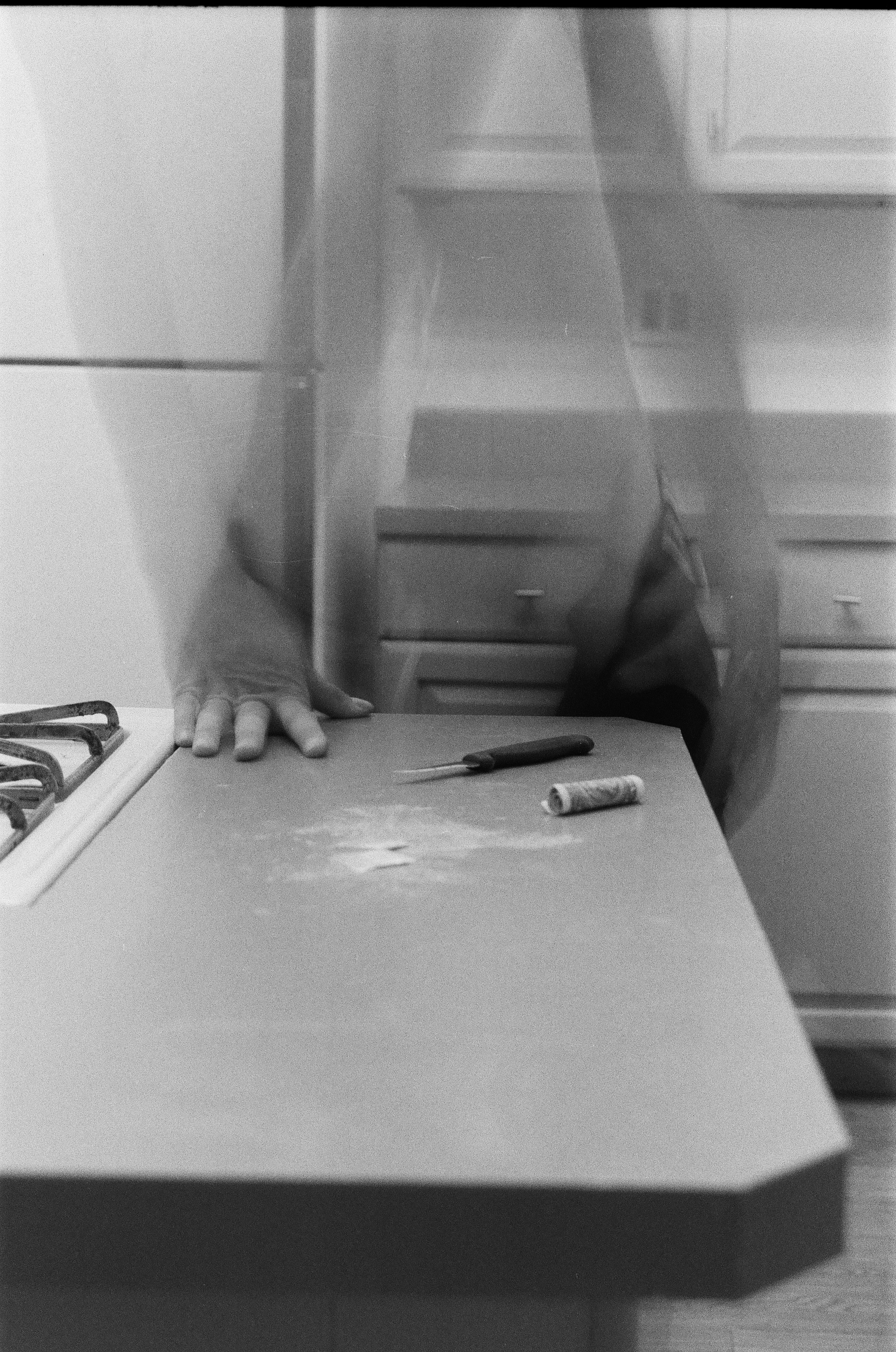

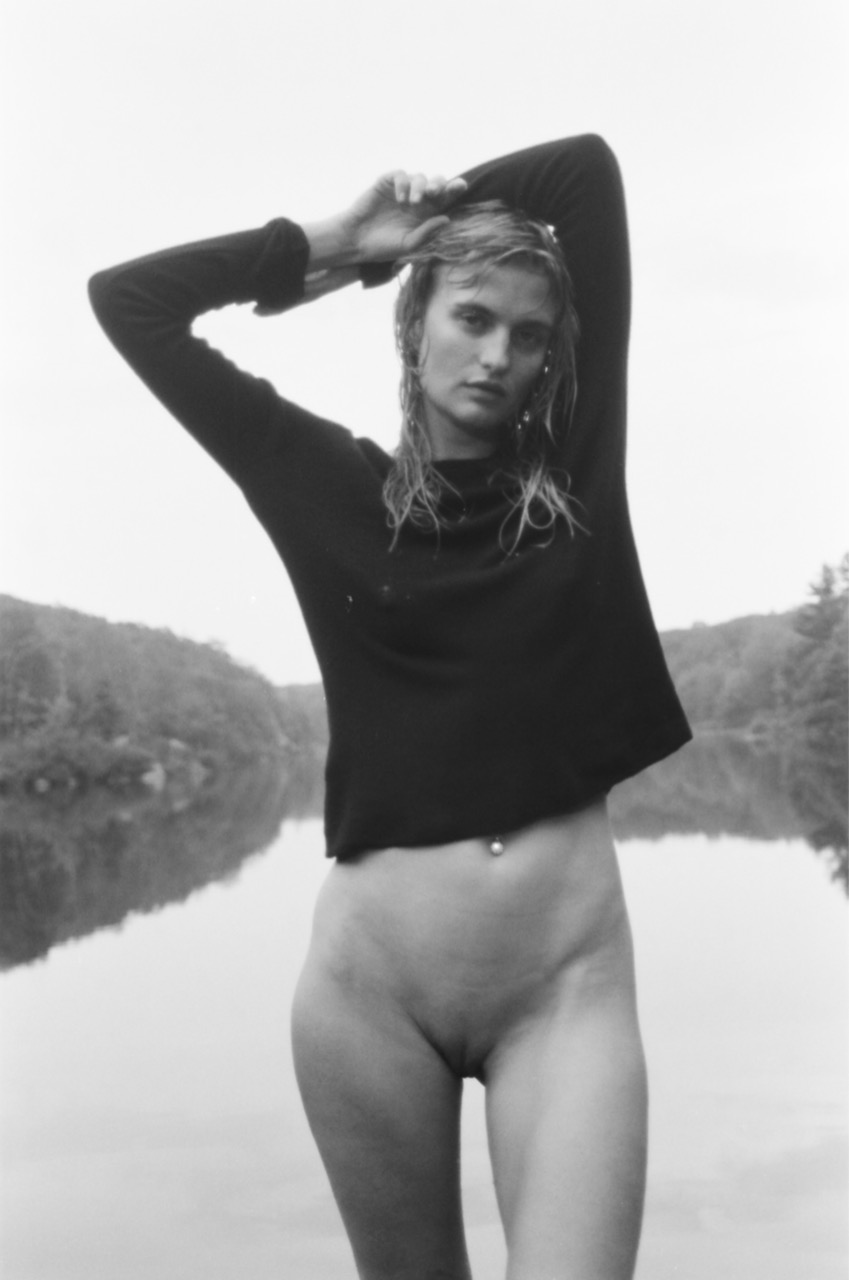

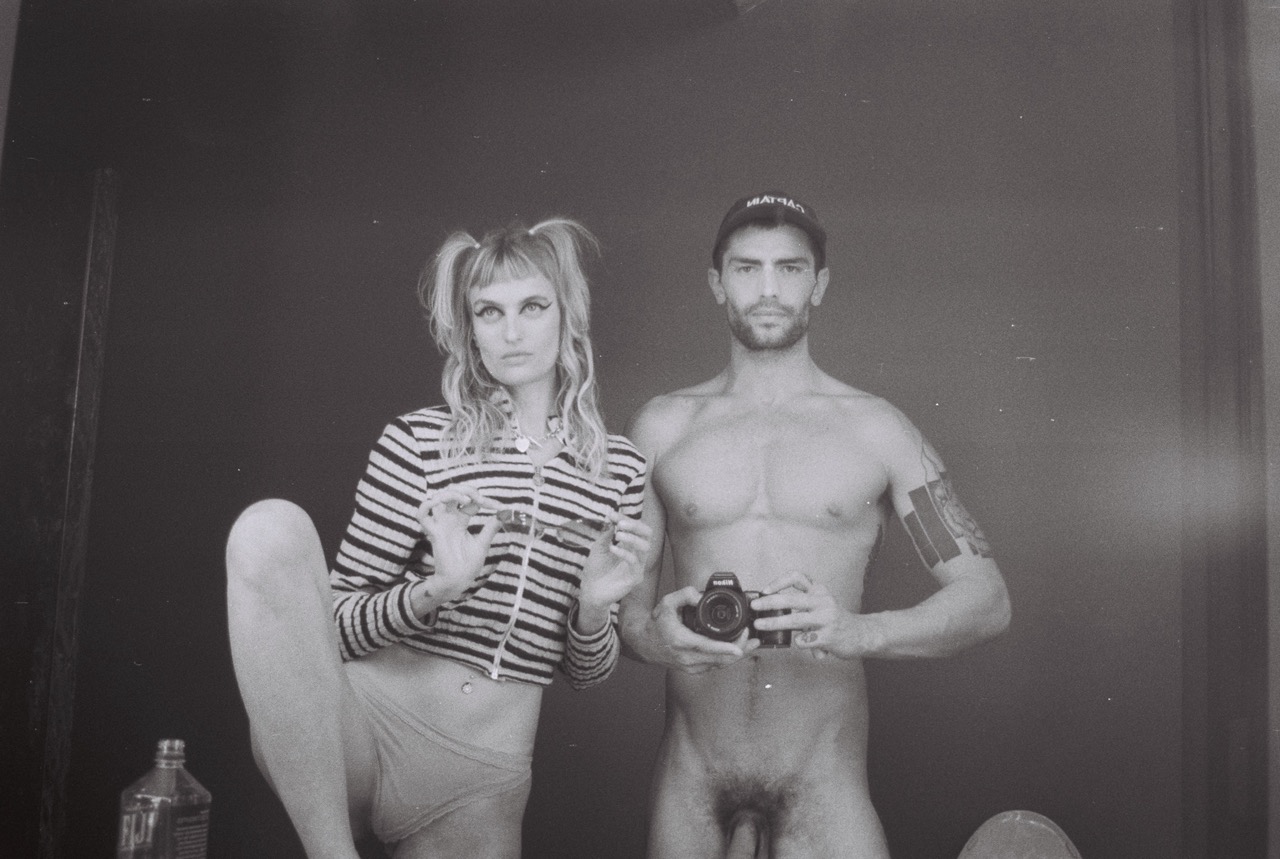

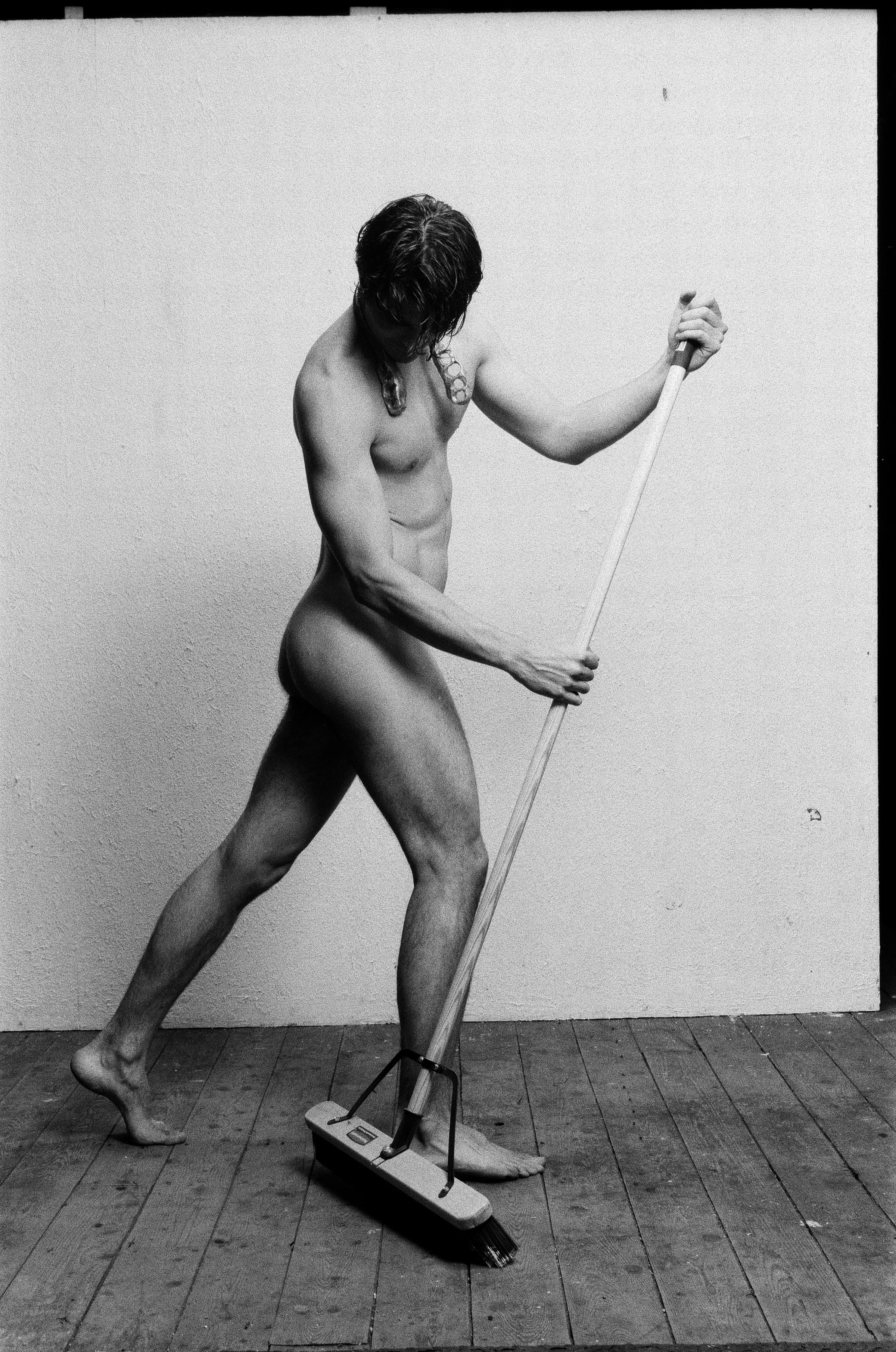

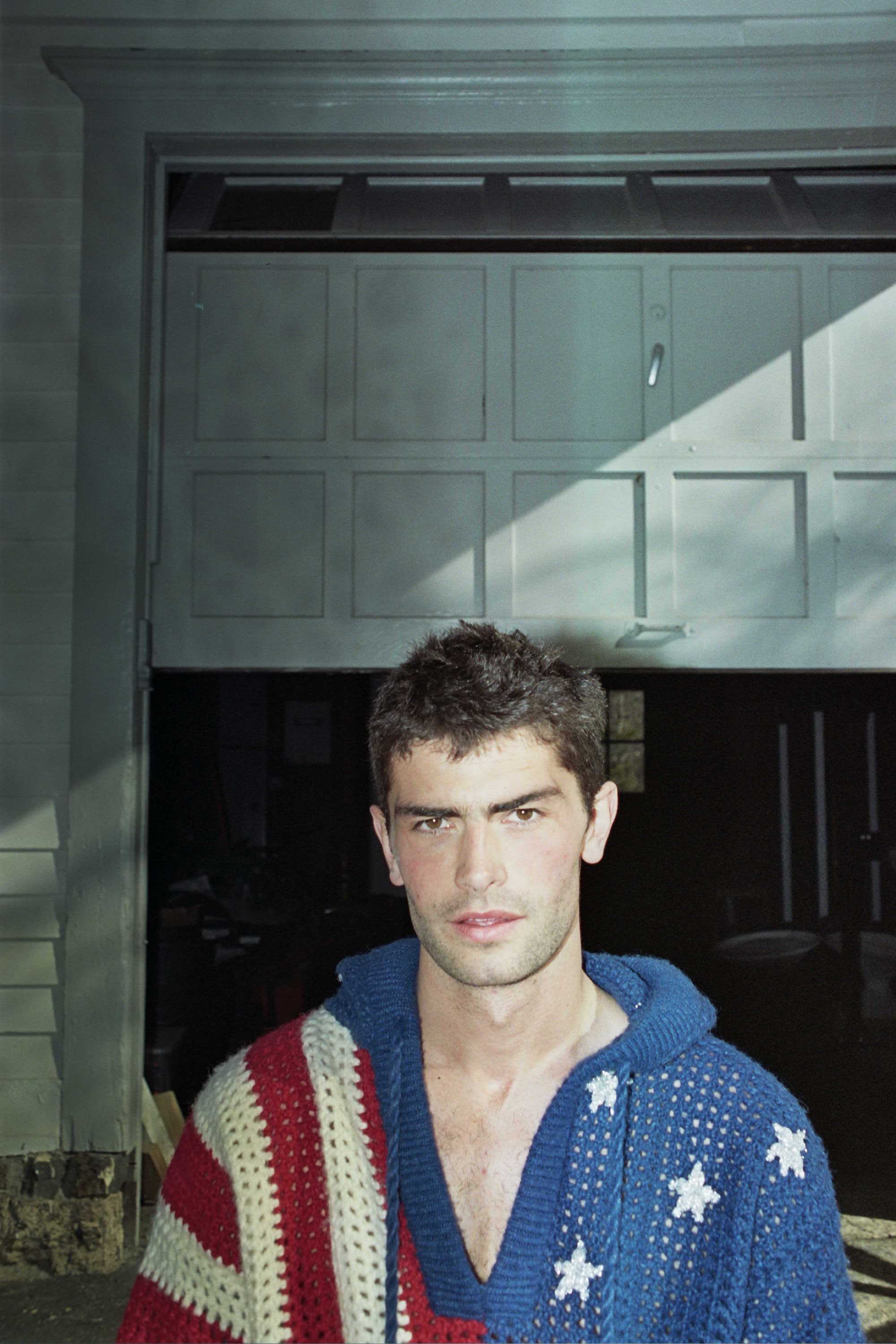

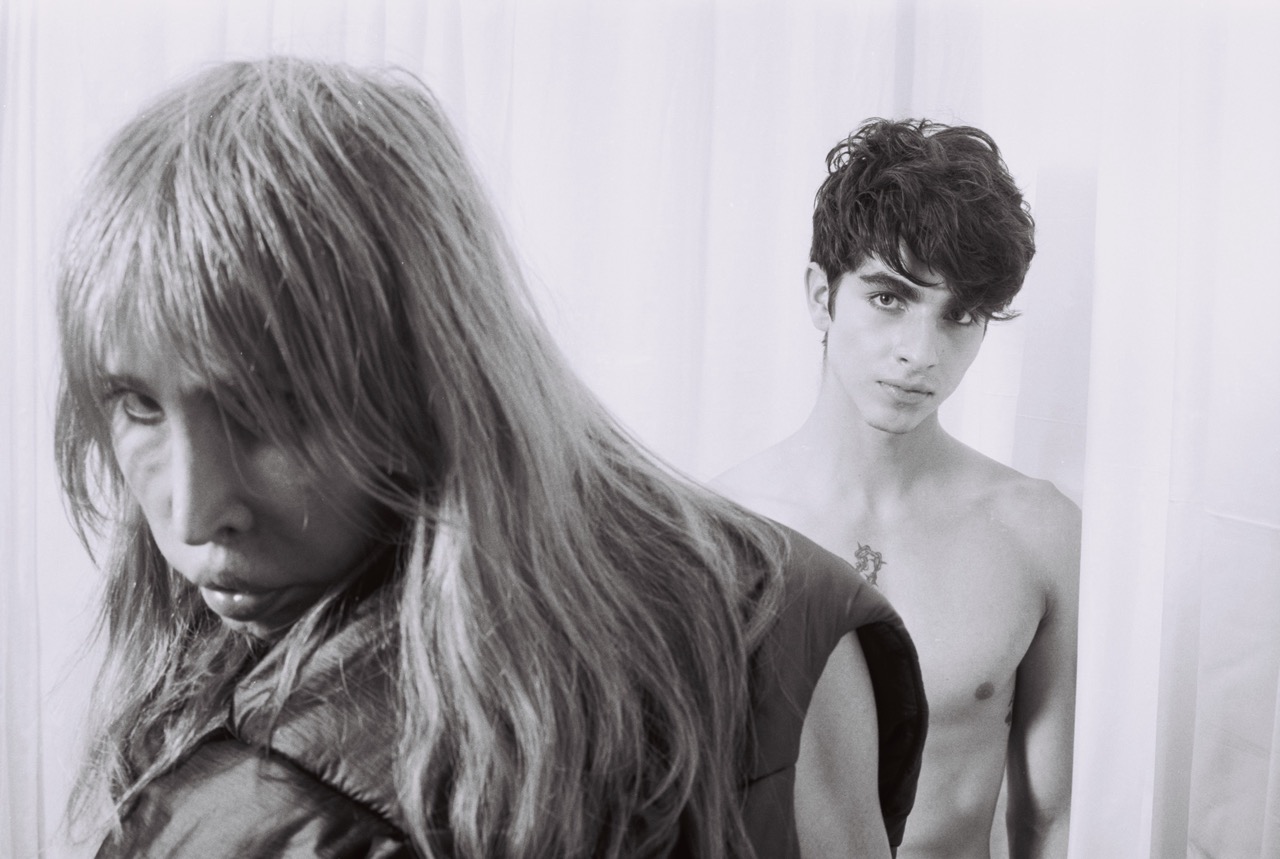

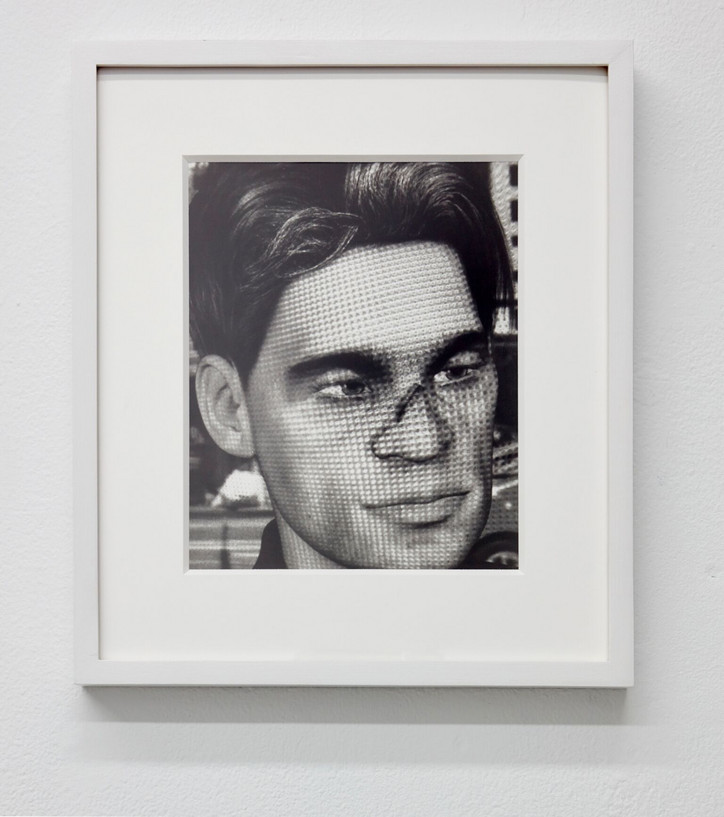

And this digital “connection” is realized, literalized, and made absurd in the intimate portraits of off-the-shelf 3D actors that comprise the remainder of Last Days in a Lovely Place. These gelatin silver prints, with the visual language of high contrast, film photography, are an analogue vision of a digital world—a sort of precise inverse of the finger paintings. These proto-photographs, made by printing negatives of screengrabs onto transparency sheets that can be developed in a dark room, capture moments in nostalgic black and white of 3D characters found on online shops for prefabricated beings. These models, meant to be downloaded and used, are captured in the moments their creators’ decided best displayed them for sale—in the midst of an awkward hug, lurching over the handlebars of a motorcycle, and curled up and hissing. The dispersal of the digital not through downloading but through the appropriation of the visual language of analogue capture and production is not just wry or ironic, rather it further troubles the familiar binaries that perhaps are not and have never been all that useful: IRL/URL, analogue/digital, close/distant. Further elliding and eschewing the boundaries of physical and digital, Darst will also be publishing a book, Lazyitis, with Soft City Printing to coincide with the exhibition.

For Darst, the difference between these 3D bodies and are own is unclear—it is our bodies that are rendered as just the lingering abstract echoes of digital touch and imagined shutter click, our bodies unfigured while 3D figures stand in photo frame. In our thrilling, perverse intimacy with the digital, it seems that we remain the limiting factor. Through these variegated representations of digital touch, Darst forces us to ask: which is the prosthetic—our phones or ourselves?

Last Days in a Lovely Place is on view at Lubov until August 26.