Laws of Motion

Preview some of the pieces, below.

'Laws of Motion' is on view now through March 9 at Gagosian San Francisco.

Lead photo: Jeff Wall, 'Siphoning Fuel,' 2008. © Jeff Wall. All photos courtesy of Gagosian.

Stay informed on our latest news!

Preview some of the pieces, below.

'Laws of Motion' is on view now through March 9 at Gagosian San Francisco.

Lead photo: Jeff Wall, 'Siphoning Fuel,' 2008. © Jeff Wall. All photos courtesy of Gagosian.

At the core of “Miss Understand” is a celebration of the divine feminine, or the spark that birthed humanity into existence, as well as a profound respect and admiration for the resilience of women to embrace the multidimensionality of their identities from within a society that has historically limited their agency to do so. She achieves this by masterfully invoking a visual language of repeating symbols: eyes, lit candles, fleshy body parts, serpents, and Barbies, etc. that seemingly invites the viewer to try and connect the dots while at the same time resisting the very idea that there is a rational or logical way to view or experience life or the exhibition. "Miss Understand" was on view at Templon Gallery in NYC through March 9th, 2024.

Emann Odufu: It took me a while to process the exhibition. I was initially overwhelmed by that level of detail. I was at the exhibition in the installation space with some friends, and we heard a humming noise coming from a box. It took us a second to realize that the box was a refrigerator. We opened it up, and there were apples in the fridge.

It wasn't until I started to look at Miss Understand as a character that I began to see her not as a representation of you solely as an artist but as a holistic representation of femininity in the modern world that I began to wrap my head around the exhibition. Miss Understand felt like a play on Miss Universe and every woman. My first question is for you, the artist, who is Miss Understand?

Oda Jaune: I’m so happy that you opened the door of the refrigerator. When I was working on the installation, I loved to imagine the viewer to experience the exhibition with their eyes and hands and to lie down on the bed, sit on the chairs, discover the overpainted books, and spend time in the space so they become part of the installation themselves.

“Miss Understand” is not a particular woman. It is not me. It is no woman and at the same time maybe every woman. It’s also for everybody who feels like a woman. I came up with the title on a walk with my daughter. We were looking at people's T-shirts because there was often a slogan written on them. She asked me if I had to design a t-shirt with only text, what would it be. The first thing that came to my mind was “Miss Understand” and I said that I would divide the word into two.

It's something in the nature of the woman that it is impossible to be understood. Extending it further, I think it’s in the nature of a human to not to be understood. How absurd is it to me that we are living in a time of so many numbers, facts, algorithms and scientific proofs that bring us further away from (our) nature. We're forgetting about magic and things that are not so easy to understand. When you have the feeling and understand something, you put it in a box, label it and maybe you get a key and close the file forever and say “Oh, this is this way” and you are limiting yourself. I feel almost allergic to the idea of labeling the world, people, history, everything that we try to put in a box.

Within the work there may be questions for the viewer, for their answers to arise but they don't need to position themselves and don't need to judge. Our world is so polarized. You must choose left or right, for or against, which constantly puts us in separation and division. How about making it more open for us to make mistakes and for misunderstandings and more freedom?

EO: I think that that makes a lot of sense. I saw that throughout the show, there's this idea of subverting duality or this idea that in the process of misunderstanding, there's this sort of mystery that is confronted and acknowledged. As the viewer, you see the exhibition and try to make sense of it all, but try as you may, you won't see it from the vantage point of you, the artist, and It's almost futile to try to understand.

I want to talk about the performance art piece happening on the show's last day, which I'm excited to see, and where you will animate Miss Understand in a personified form. As an artist, I love that you dig into the multidisciplinary aspect of your practice and constantly push the limitations of how you engage with your audience. I read that in the last show at Templon in Paris, you had a hologram of the Tree of Life, and now you're activating this current exhibition through performance art. Can you talk about how you're constantly reinventing your practice and your approach to toggling between these various mediums as you engage your audience?

OJ: I love that you found information and the little journey that I had with the hologram. I loved it because it was the pandemic, and the real situation where we could reset individually and as a society. I was asking existential questions, and I thought about how we're living in a world that is, for me, even though it's so dominated by inventions of our time, it is still quite magical. It's almost like another reality within our reality. I was working on this show during covid lockdown thinking about how there’s something invisible you couldn't see, you know it's in the air. I found it fascinating that we were in such a frenzy over something invisible and how it could, for a moment, change everything in our world. This thought process around visible and invisible, tangible and translucent, leads to an interest in holograms. The more I researched, I understood that I would have to create my own technique for creating a hologram, because the best things happen when you have a limited budget.

I said “OK, let's think about what we can do if we improvise.” So we created something, and it actually worked. It was like magic because we didn't have much, and it was such an improvisation and the people who loved it from all age groups were touched by it. For me, it's about how real I can make an idea and what techniques permit me to execute those visions.

I was trained as a painter and when I was younger, I really loved observing the human body. I thought it's just so incredible. Humans in general. I really love nature and observing the light and the shadow and how everything changes constantly. I honestly don't remember a moment in my life when I have been bored. What a stunning experience it is having eyes. Painting oil on canvas is the closest I can come to what I have as a vision. At some point, I reached a stage where I can paint everything that I imagine, so I created sculpture to see how I would feel when my ideas become three dimensional. When I was a young girl, I loved working with clay, the softness of it. I was also intrigued by wood and stone, marble but then I was told that, because I was a woman, I would only be able to work on small things because physically I would never be able to do what men can. I accepted that and focused on painting. Because I wanted to be as free as possible as an artist and I do love painting in an unconventional way, but I didn’t stop loving sculptures, so later I reapproached sculpture again.

One day, my daughter asked me if I wasn’t a painter what I would do in my next life. I realized that I would love to do movies, but I want to do movies that I only need to do myself. That's why there are six short videos in the exhibition and I loved making them.

EO: I'm also a filmmaker, and when I was in the installation, I thought that as I looked at the videos, whether you are shooting the videos with a crew or you're shooting them yourself.

Alone. I really love making films, combining pictures and sounds. The whole thing is moving. With painting, you have just one shot. A study found that visitors look for less than two seconds, turn and read the explanatory text for an additional 10 seconds and then move on. So, you have to decide which moment to paint and that takes months and months in order to make a difference in a span of seconds.

EO: And now you're venturing into performance art.

OJ: I am very excited though about the performance art piece because Claudia is a very special human being that I love as a dear friend. One day, she showed me something with her hands and the way she moved her finger in a way to symbolize humans, it was like a symphony, and I imagined it as a whole movie. I asked her if she wanted to collaborate for the exhibition. I love to imagine what she is going to do and love not knowing what is going to happen on that day. It’s the same with all of my paintings. When I start painting, I never know what's going to happen. What I dream of is creating a feeling of “Miss Understand “ being a real human - only the feeling that was at the core of our collaboration for the performance you are going to see on the final last day of the show. The aim was to put this feeling in a real human that will grow and materialize itself in a living, moving, breathing, heart beating woman inside the gallery space for 8 hours existing as real as every one of us. Claudia will be performing and the viewer can enter the space and decide how close and involved they want to be. Claudia Hilda is for me one of the most incredible artists with that one of a kind ability to become a pure feeling by giving up on all she is, on all knowledge and abilities, techniques and styles she has, the language, the speech to become Miss Understand.

EO: There is a quality of artistic rebellion in your work that I enjoy. Both aesthetically and with the symbols you use very well. The viewer's experience of your work has been described as deciphering a crossword puzzle, a complex web of various cues that appear from out of your subconscious and that force the viewer to confront their relation to the world and their internal belief systems. Miss Understand does not exist in a vacuum and builds on a visual language you have built throughout your career. It's a language only you speak, but the viewer can feel it. As an artist, how did you come to know yourself in such a way that you can render your subconscious into a visual language that people can feel?

OJ: I don't know but I'm going to search for an answer to give you. The thing I can tell you is that I can't work if there is somebody else around me. If there is someone else in the studio, I never reach the concentration that I need to forget the outside world. I start with something that moves me. There are certain things where there is a longing. Something I am deeply moved by, something I can’t find peace with unless I can transform it and bring it to the other side.

It doesn’t even need to be politics; it can be something like how we come into this world without choosing where and when you are dropped here and then you deal with it and then on top of that you're going to be taken away at a certain moment. Maybe this is what I really don't like as a feeling, probably like all of us I don’t like the feeling of fear or the feeling of not being able to change things or that I don’t have any power to make a change. In a way, I search for a way to deal with the reality of what is really happening in the world with eyes wide open. I reject closing them. These things move me and touch me, and I want to fight. I did start as a child with the dream to change the world. I suppose painting was my tool.

When I was 12, I moved to Germany. I could not speak the language and the kids were kind of cruel and thought I was stupid. I really couldn't express myself, I just had the basics. So, I started drawing to communicate and it worked. They were able to understand me. In this moment, I saw how many things you can say with an image. If you think of all the emojis that we send and how one heart emoji has thousands of words inside of it and there is something so open about it.

When I was a child I loved going to the library, and I would search for books with images, and I spent hours and hours and I would “read" through observing images. So, I think it's the way I get the most information. I believe my ideas come from tapping into my subconscious. It’s through the subconscious that everything comes. Your subconscious is working for you during the day and night when you're not conscious. It's a huge sea of everything and it has its own intelligence. For many centuries people believed a lot more in this other part of our intelligence and it’s a lot less respected these days. Today we are more confident about the visible things, the rational, the facts that can be scientifically proven. However, there is some truth on the other side and when I reach the point of being in tune with it, it is usually in the morning. I just love silence when I'm alone. I always start quite disciplined and controlled, but there comes the moment where all this control is lost and I’m working and not hungry and I don't know how fast time goes by, this is the most precious time and that is where the important decisions take place.

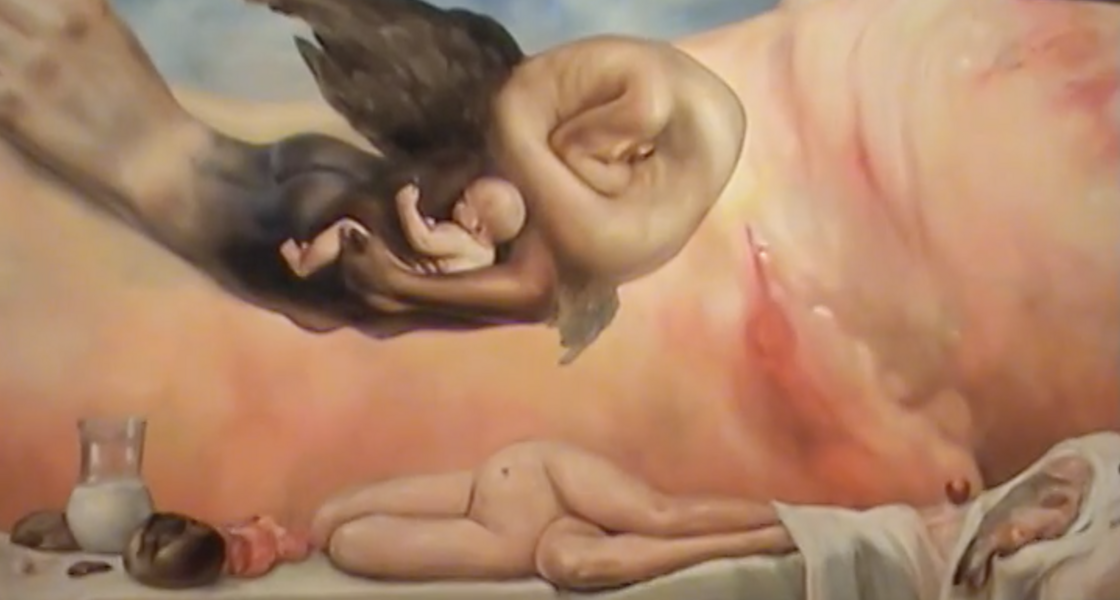

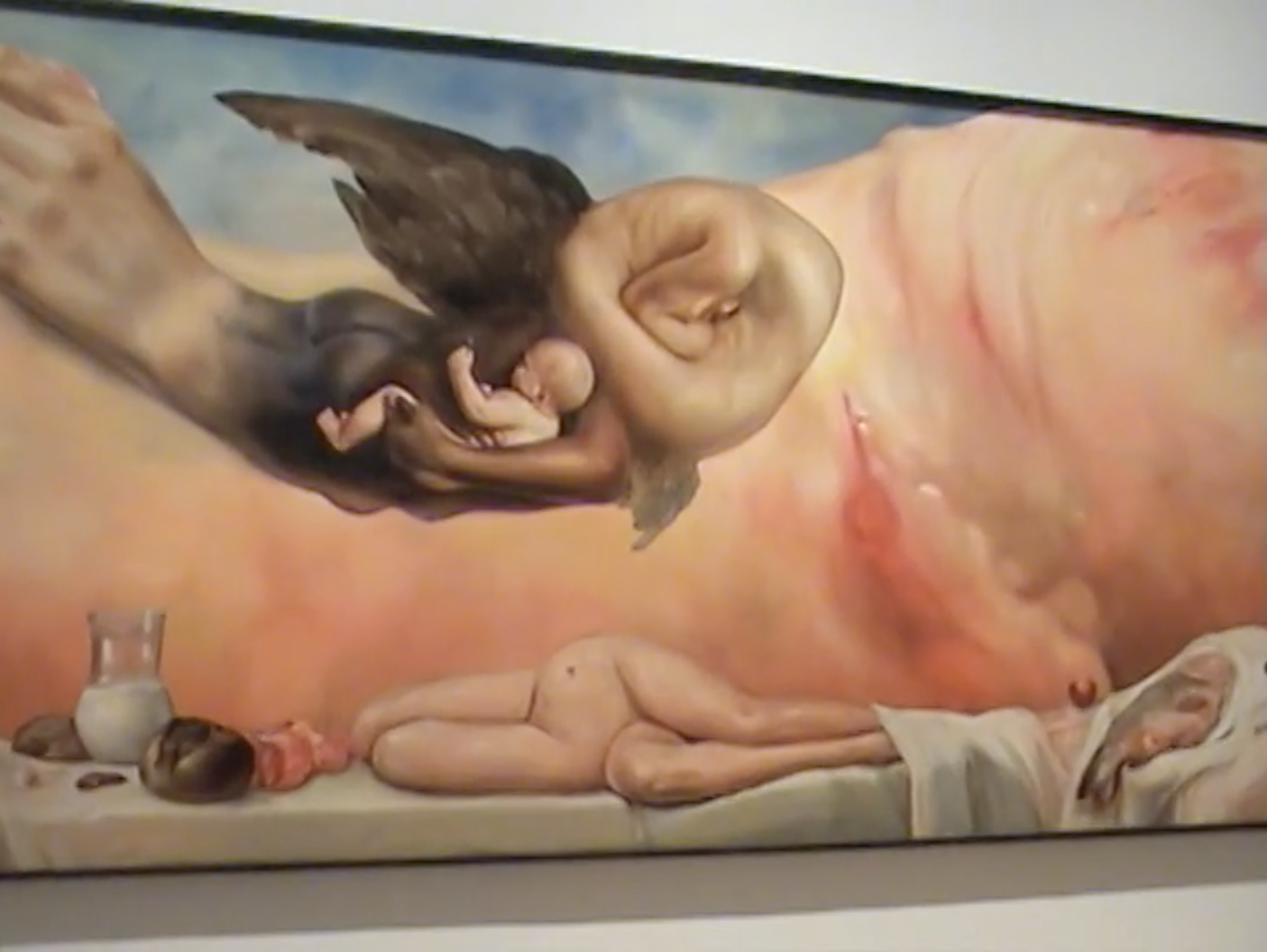

EO: Birth and creation ( to ourselves, to the other, to the world) is a strong theme in your practice In this exhibition we see the connection to Birth through your depictions of the womb and pink fleshy matter, most prominently in your work entitled "M is for Mother". It's also seen in your depiction or cap nod to the biblical creation story and how that has shaped the perception of women in modern culture. Can you reflect on this theme of Birth and Creation and how it's a thread carried throughout your practice and even into your artistic philosophy?

OJ: Someone told me you are born many times in your life, and you also die many times in your life and I love that, but I wanted to talk about the very first time. The biggest painting in the show M for Mother, is about coming to earth, dedicated to the one that gave us life, the biggest present, to the mother. We often think we have freedom of choice in life, but the biggest choice has been done for us, it is not done by ourselves. What happens? Where do we come from? It all begins with pain, the first breath you take on earth is painful and your mother will be in such pain. They say that when you're born several times in your life very often it happens after a very difficult situation and you're able to start a new life. One of the most dramatic things that can happen in life is having a chance to be reborn, reinvent yourself, to reset and start new. Many of the paintings capture moments of change or transformation. You have someone of something becoming something else.

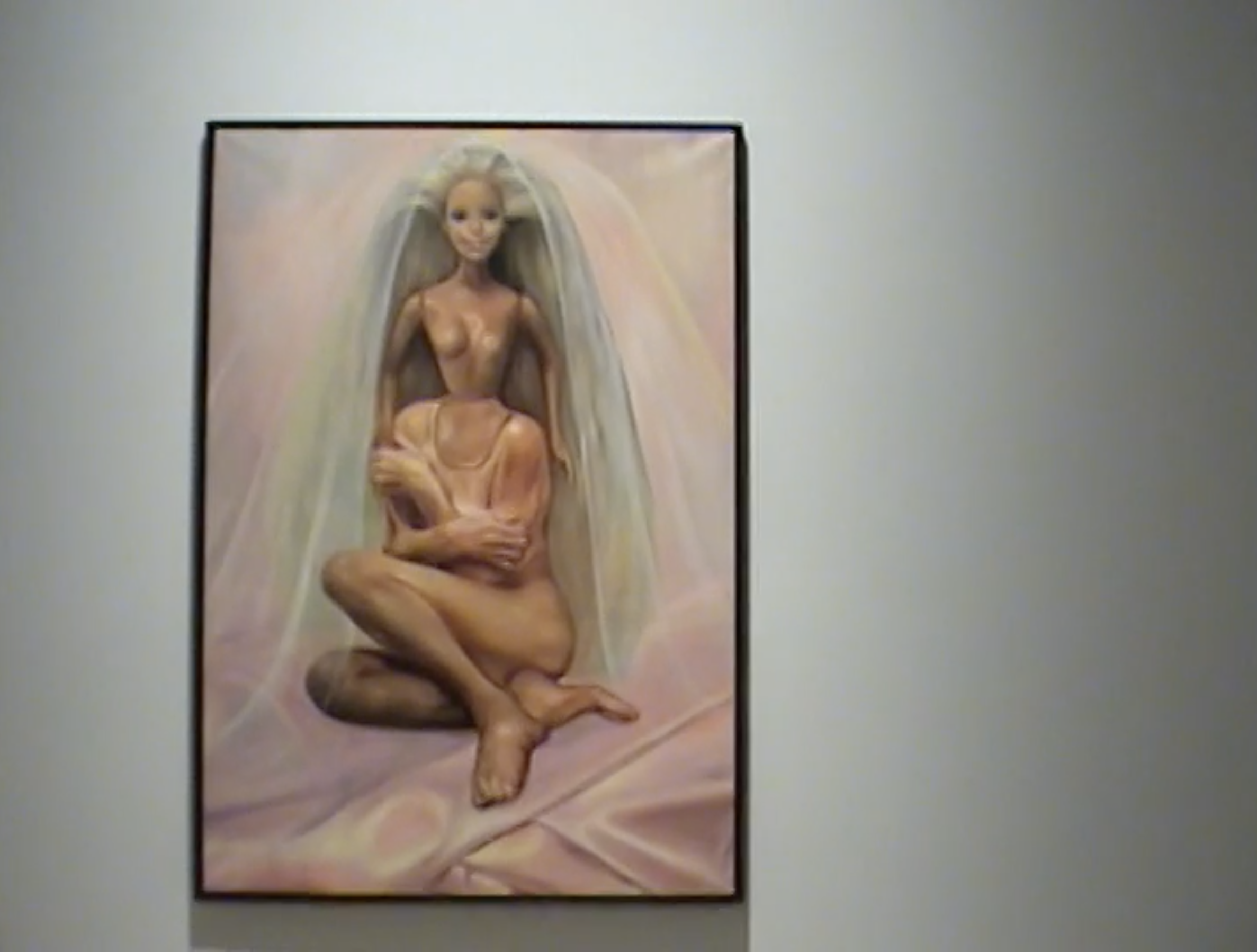

EO: One great example is "B, like Barbie."

OJ: Yes, B like Barbie is also about that. I had many barbies when I was a child and when I started painting this painting, I had no idea there would be a movie about it and it had nothing to do with that. When I was in New York, I went to see it, but I found that I just really wanted to fall asleep. I didn't watch it until the end, but what I did see was this constantly beautiful young plastic doll. But you are never the same. Depending on how you feel, how much sun you have taken in, how healthy you are, what you ate, how you slept, how much water you drink, you are never the same. Even after you go to sleep, your mind and feelings are still active because you had certain dreams that you might forget on the next day, but you change. Regardless if you forget your dreams, you are still altered by them. You are not the same. So this idea of one-dimensionality is problematic. Birth is something to be so grateful for and it is important to never forget that. At a certain point, there is so much thinking of who I am and not of how I have been born.

Pictured Above: 'B for Barbie,' 'M for Mother,' 'G like Guerrilla Girl' (2023)

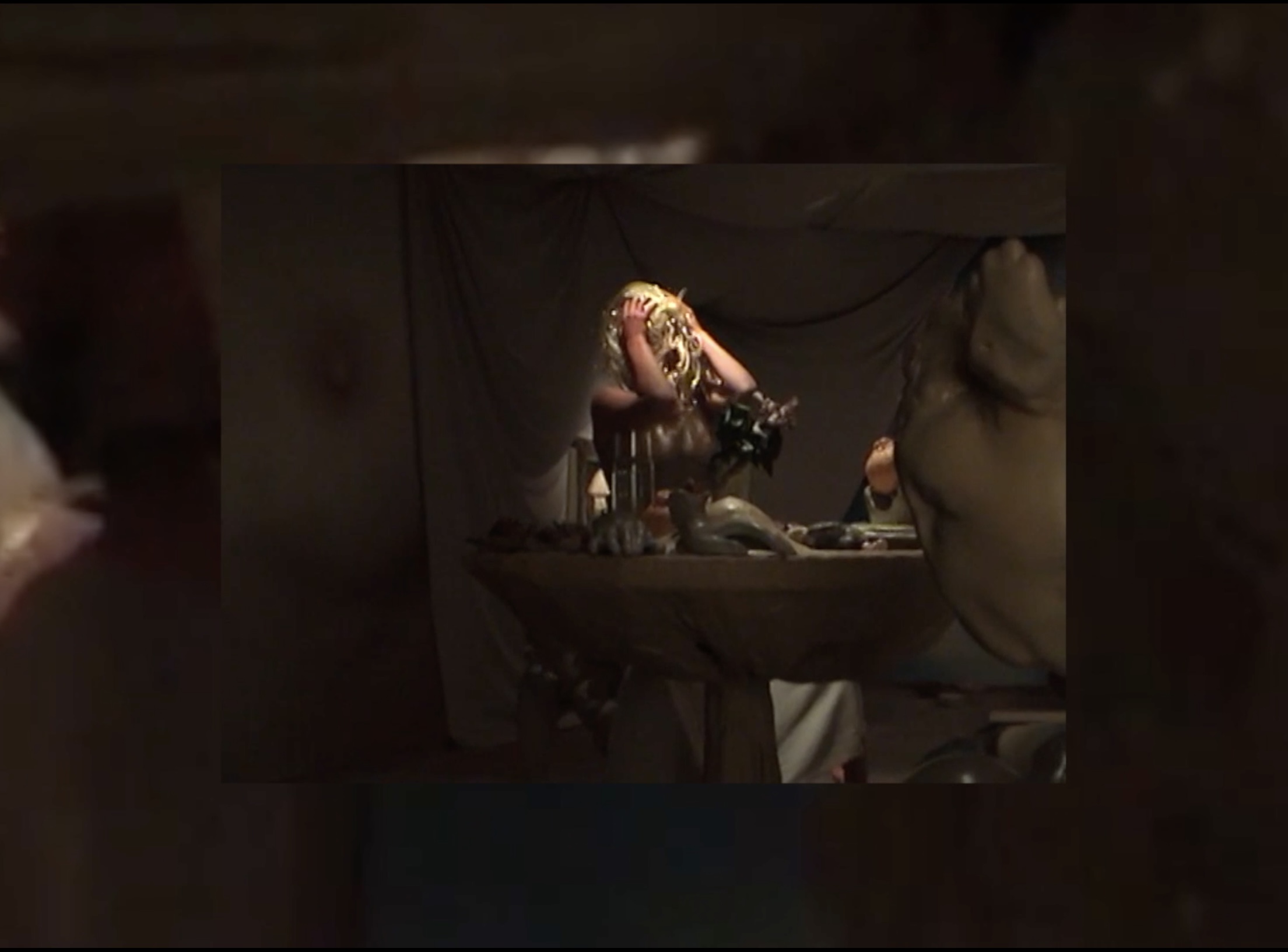

Footage from the closing performance by Claudia Hilda below.

This one-of-a-kind vehicle integrates color-change technology with the signature colors and geometric patterns we’ve come to associate with Esther Mahlangu's work. To ensure the faithful recreation of every intricate detail of the ornate artwork, the BMW i5 Flow NOSTOKANA has been fitted with 1,349 individually controllable sections of film.

The complex colors and patterns showcased in the artwork offer a glimpse into the future potential for customized vehicles that fans of BMW’s innovation can look forward to. We took time from exploring the artwork to catch up with Stella Clarke, BMW’s research engineer as well as Esther Mahlangu in order to understand both of their perspectives.

What about Esther makes her the right artist for BMW to collaborate with?

Stella Clarke, Research Engineer Open Innovations, BMW Group - I think there's a number of things there. So, the journey to this car started about six years ago and before we even had prototypes, I had a pitch deck to try and convince people of using E Ink in a car. And at the very end of that pitch deck came a picture of her looking at her art on the dashboard with a huge smile on her face. And that was the moment where people understood what I wanted to do with E Ink. So that was really a key moment and a key inspiration for everything that happened after that.

Second of all, it just fits in really well together, her art with the idea of color change in multiple ways. Of course the art is very colorful and the ability to kind of change the color brings a dynamic element, a modernity into her art. Throughout the history of this African art from the Ndebele culture, there's also a certain progression in there. They started painting with earth colors, just colors of the materials that you had around. And then when acrylic colors came, they moved onto that and she was the first person to take this art and put it onto canvas. So innovation has always been a part of her and her art as well. And so this is a way to continue the story of innovation with her art on our car. And she did paint the 12th art car BMW art car, which is quite legendary. And so this was also a nice way for us to pay homage to her art car while also showcasing the innovative side of BMW.

How do you think her style and vision compliments BMW's design philosophy?

Stella Clarke - I think the playfulness of her art, and the joy in her art fits together with the joy of what BMW tries to bring to its customers and the products that we make.If you try to ask Esther philosophical questions about her art, she says she just wants to bring joy to people and she wants to kind of show her tradition to the world. And I think it's the same thing that BMW wants to try and do, bring joy. It's a part of our slogan, right? Bring joy to the customer. And also a certain amount of heritage is also in there with BMW, that we are also proud of.

Why do you feel it's important for BMW to merge the worlds of art and automotive design?

Stella Clarke - I think BMW has always supported the arts and here we're seeing a kind of fusion of art and innovation. And I think those two go hand in hand. I think something that's innovative and something that is creative is something that brings joy, brings light, perhaps even a certain amount of disbelief. And we've done this with our changing colors so far. We know that people often can't believe what they're looking at. And I think art often aims to do that as well, right? The art kind of aims to push your mind. It aims to delight, it aims to bring you joy as well. And I think that's how art and innovation can come together. So I think we can both learn from each other because we both have the goal of delighting and bringing joy to people.

Do you think art, and this collaboration in particular, will shift perceptions of traditional car design?

Stella Clarke - I think so. I think it's a wonderful playfulness that we're showing here. And I think not only this car, but the other cars that we've done with color change so far with E Ink. There, we showed cars that can change their colors and we know based on the reaction that people like to express themselves with their car. So this really brings a new element into car design. It means that you, yourself, every owner of their car can become their own designer. And at any given day, you can choose how you want to express yourself with your car. It's a new dimension in terms of car design.

What about BMW as a brand makes them the right fit for a collaboration?

Esther Mahlangu - I have a long and mutually beneficial relationship with BMW that goes back to 1991. They have proven their interest and commitment to art over many decades through the BMW Art Car Collection, sponsorship of art fairs, work with museums, and now my Retrospective Exhibition and the tour thereof.

What considerations have to be made when collaborating with such a big company like BMW?

Esther Mahlangu - BMW has been very easy to work with. I have not had to consider many things in our collaborations. They have proposed different projects to me which I have agreed to do and they have been very successful. My gallerist proposed my Retrospective Exhibition to them, and they agreed to support it for which I am grateful.

Were there any creative limitations?

Esther Mahlangu - There have not been any creative limitations other than the medium itself. They have provided me with a car, and I have looked at it as a medium on which to paint or apply my designs.

What elements of the artwork do you feel speak most to your South African heritage?

Esther Mahlangu - I was taught the art of Ndebele design as a young girl as is tradition amongst my people. Everything about what I create is therefore closely associated to South Africa, something of which I am very proud.

Has there been a shift in the creative process since the first BMW collaboration in 1991?

Esther Mahlangu - My last two projects with BMW have been very different from our first collaboration in 1991 as they did not require me to paint onto the vehicle. Both used the latest technology to apply my designs to the cars.

Was it difficult to adapt to and welcome technology into the fold?

Esther Mahlangu - It was a simple process to include my designs whilst I expect that it was more difficult to come up with the technology that allowed for this.

The world, at least in 1937, seems to have agreed on the powers of the lamb. That year, the artist Paul Cadmus opened his first solo show at Midtown Gallery in New York boasting artworks of male physiques and satires of American nightlife. Everything from his show sold out. It drew a record-breaking audience of seven thousand homosocially curious lions, lured in by an artist compelled to depict men as if they were potent lambs as evinced in his painting, Y.M.C.A. Locker Room, 1933. It was all very gay. For this, the artist garnered mainstream attention and inclusion in art history. Life magazine fueled America's intrigue, emphasizing Cadmus’ cheeky fascination for depicting, “the play of muscles and the stretch of skin above them.” (Incidentally, Cadmus’ men appear with little if any visible signs of body hair, resembling sheared lambs free of wool coats, perhaps something de Beauvoir would have found less repulsive).

A few years later, the 1941 Encyclopedia Britannica entry for ‘Famous Paintings by Modern American Artists’ linked Cadmus with Regionalists Grant Wood and John Steuart Curry and soft psycho-realist Edward Hopper. This moment of late American modernism would not last. Like all movements in art history, they, too, were succeeded by another scene. Cadmus was met with fierce condemnation and brutal acts of censorship for his boisterous tableaus of cross-class contact rich with sexual innuendos while his less gay peers were succeeded by the Abstract Expressionists. The Ab Ex painters were sponsored by clandestine CIA “donations,” and written with great esteem by academic art critics weaponizing their institutional powers of intellectual prestige to refashion history, whether that of art or sexuality, to their own liking.

History loves persecuting sexual minorities. There is no exception to this, not even from the ancient Greeks who were rather generous with their sculptures of naked mortals, demi-gods, nymphs, and goddesses. In response to an email I wrote to A.B. Huber, one of my undergraduate thesis advisors, Huber shared this anecdote, “I kept thinking about the fact that when the first stele of hermaphroditic figures were being made in Greece, actual intersex babies were ‘put out to sea,’ that is exposed and drowned as monstrosities that threatened the community. Sometimes non-normative bodies are celebrated in art or ritual objects but loathed in reality.” Why is the reality of everyday life often overlooked, censored in art history?

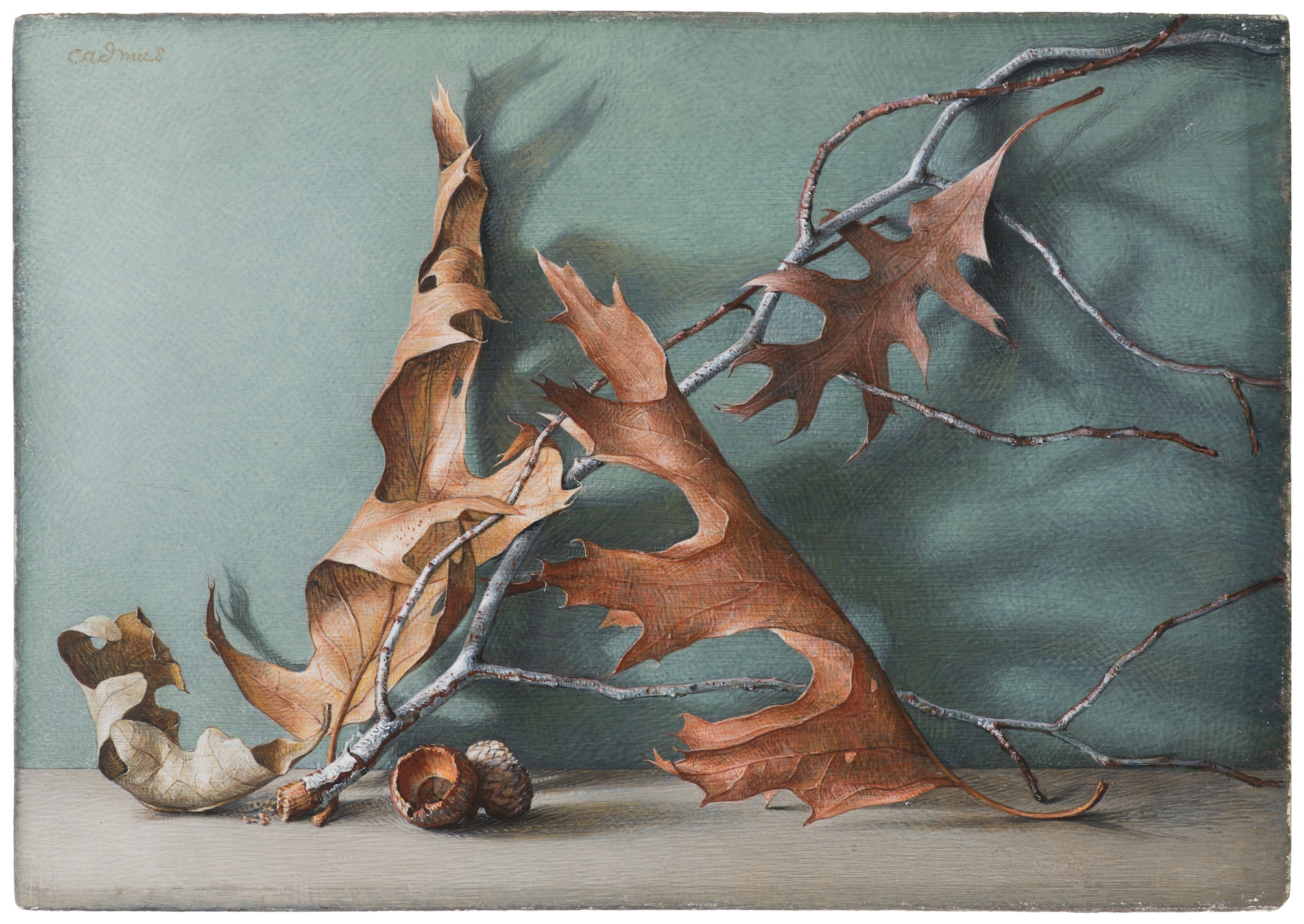

Whatever, for Cadmus and Cadmus’ friends, life was always a beach. In February of 2024, D.C. Moore gallery showed the artist’s first major show in over 20 years, Paul Cadmus: The Male Nude. It relied heavily on works of beauties traversing Fire Island’s sandy shoreline, beachside mansions, and White Oak and Red Swamp maple-covered loveshacks (Camp Cheerful, 1939; Pine Cone and Bark, 1955; and, Winter Still Life, 1970). They circulate across the gallery’s scarlet-colored walls. There are several still lives and dozens of nude figures drawn with fast, fluid marks or painted with egg tempera and highlighted with crayon. His figures have flesh that bulges or twists similar to artists like Tom of Finland or Jiraiya. However, what distinguishes Cadmus from these guys is that his figures appear to glow to the point of otherworldly enchantment.

Some figures read and eat apples at the beach like in Two Boys on a Beach, c. 1936. Nearby a boy yawns. Others lounge at ease and yet appear to be stretching. It’s uncanny.

Narcissus: Study for an Homage to Caravaggio, 1963, 1983

Tempera and ink on board, ca. 1963; crayon added in 1983

Collection of The Tobin Theatre Arts Fund, 75.2007.

Courtesy of the McNay Art Museum, San Antonio,Texas.

A luminescent boy in one tempera, ink, and crayon drawing, Narcissus: Study for an Homage to Caravaggio, 1963, 1983, lays sprawled out on a bed of Fire Island’s feathery grasses, like soft rush and switchgrass. His gnarly, lean flesh folds around himself as if frozen mid-motion while tumbling downhill. His firm ass protrudes at the center of the drawing. He arches his back. It creates a nice shadow-line that runs through the length of his spine. His neck, head, and blonde and white curls all meet at the end line. His head along with an outstretched left arm fall off a bayside barrier. They hover above murky saltwater located at the bottom of the drawing. His head peers downward into the water while his fingers reach out to his reflection. In this intricate tableau, the boy becomes a focal point, not merely a subject but a representation of desire itself. His naked form, frozen yet seemingly in motion, with an outstretched arm drawn in a phallic manner, invites his reflection as well as the viewer into the scene. His outstretched arm inches closer to the picture plane, coming towards the viewer. The viewer stands outside the picture, wading nearby in the salt water just beyond the boy’s reflection. Here, the artist blurs the boundaries between observer and observed, lover and beloved.

Cadmus was a huge fan of triangulations. The triangulation inherent in this composition echoes the complexities of attraction, where the paradoxical interplay of both the law of desire and the rule of seduction unfold. Something to mention, especially, about desire and seduction: desire follows the law of gratification whereas seduction follows the rule of intensification. For the desiring subject who breaks the law of desire, they are punished. But like most lawbreakers, they’re given another chance to play again once penance has been paid. Seduction does not let you play again. It follows the rule — not the law — of intensification. Once the seducer breaks the rule of intensification (becoming avoidant, anxious, or secure to the point of barrier breaking intimacy i.e. empathy) they must exit the scene. The game of attraction ends.

Between the boy, his reflection, and the viewer positioned just outside the frame, a delicate dance assembles. The boy's gaze fixates upon his own image. It’s a gratifying manifestation of his beauty. But granting that gratification threatens to extinguish desire itself. In most versions of the story of Narcissus, the boy dies once he falls into his reflection. If this drawn boy falls into the water, he would be breaking the rule of seduction — not desire — by choosing to end his life. Instead, he intensifies seduction by continuing his gaze as he reaches out to the viewer. His beckoning gesture asks the viewer to participate in this erotic scene. We, the viewer, are gratified by him including us in the scene. His hand calls for the viewer to make a decision: to grab his hand and roll along with him on solid ground or to pull him underwater. Here is both desire and seduction continuously at play. The boy's control over the scene is tenuous, contingent upon the triangulating motion of desire and seduction. The story only continues, though, if the viewer grabs his hand and joins his decelerating tumble.

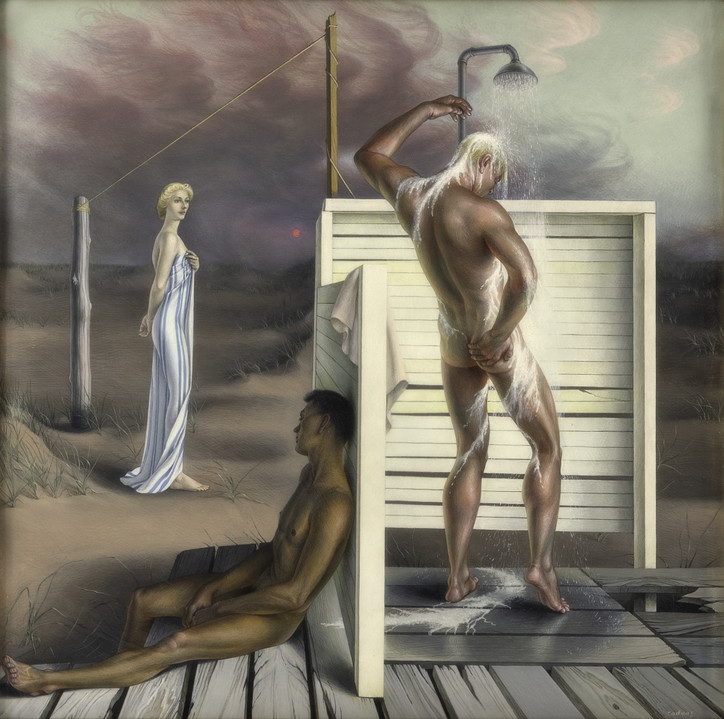

The Shower, 1943

Egg tempera on pressed wood panel

15 1/4x15 1/2inches

Private Collection

Elsewhere in the show, there's a painting showing a hunk covered in droplets and soapy suds. He is enjoying an outdoor shower (The Shower, 1943). A woman wrapped in a bed cloth watches as a wildfire summer sun burns behind her. Below the hunk is a skinny man who reclines, patiently waiting to be summoned by either of these two lovers. Again, triangulations were no stranger to Cadmus’ artistry and life. The artist took part in a collective with Jared French, Margaret French, and himself, colloquially called PAJAMA as shown in the photograph on display, Paul Cadmus and Jared French, Fire Island, 1941. The throuple lasted for a significant portion of his life. This was brought up several times during a packed-house conversation on the legacy of Paul Cadmus and Fire Island this winter. The conversation was shared between art critic Justin Spring, BOFFO co-founder Faris Saad Al-Shathir, and photographer Matthew Leifheit. But, the artist was more than his triangulations. He collaborated with a cohort of mostly white creatives like the photographer George Platt Lynes, Lynes’ on again off again lover, the MoMa curator Monroe Wheeler, and the painter George Tooker. In reality, these were his companions. This was the art historical movement in which he found pleasure and safety to be himself. He helped build it and so he belonged to it.

One of the artist’s favorite scenes was wherever water meets land. More often than not his scene was the beach. In the most literal sense of the word, a scene is a moment of “intense affection,” similar to scenes found in a book or a movie. They also appear in drawings and paintings. Social scenes, too, are moments of “intense affection” where both pleasure and safety are interconnected at a much larger scale. What feels special about Cadmus was his knowingness that much of his scene wouldn't last. He navigated his faggy way of life, the polyamory, the earnest pursuit of some idealized human form, the thumbnails of bullish men, sailors, twinks, trade, glammed out dolls, gangsters, hookers, beefs, queens, faeries, all entangled and enthralled with one another.

The Fleet’s In!, 1934

Etching

7 1/4 x 14 1/8 inches

D.C. Moore’s founder Bridget Moore added to the conversation noting that the government did not value a lot of the artwork created for the United States Public Works of Art Project (WPA) after the war and, unbelievably, sold many paintings for linen scrap for pipe fittings. These works, along with artworks by Cadmus' peers were sold at garage sales or thrift stores. Further to the point of trash, it’s no surprise that one of Cadmus' paintings made while a member of the federal government funded WPA was removed from public view. Perhaps it was because he was outing all sorts of men in the military. “In 1934, one of Cadmus’ very gay paintings, The Fleet's In!, 1934 (it would later inspire a major motion picture), was quickly removed from public display. It was stolen by a retired navy admiral who, contradictorily, installed it at a men's-only Alibi Club in Washington, D.C. It lived there for four decades. A year before Cadmus' The Fleet's In! was removed, Diego Riviera had his mural burnt off the wall of Rockefeller Center because he wouldn’t remove his portrait of Lenin from the center of it. All the best artists were queer communists,” shared an audience member during the conversation’s Q & A. By outing the whole military, did Cadmus fuel military turmoil?

Spring confidently responded. He seemed to think this was most likely not the case. He noted that figuration in art history has always been queer and that Cadmus’ practice of queer realism by means of figuration was not all that political. The critic seemed to be missing what the audience member was suggesting. Said audience member responded, “I suppose I agree with you that figuration has always been queer (because people are),” echoing Huber. “However, America did put Cadmus’ style of figuration entirely back into the closet to avoid the issue of America’s very public queerness. America wasn't ready for queer figuration, but Cadmus was insisting on it 90 years ago!” furthering Huber’s illustrative example. The packed gallery stirred at the lamb's captivating come-on. A faint smile materialized on the critic's face, begrudgingly acknowledging the lamb's charm.

There’s more to share. Continuing de Beauvoir’s observation, she notes that, "If the prehensile, possessive tendency exists more strongly in women, her orientation... will be toward homosexuality." Here, de Beauvoir is not wrong. Homosexuals, those women attracted to women or men attracted to men, have an intimate understanding of attraction’s complexities and know best how to navigate, if not totally transfigure, scenes of intense affection and desire. They tend to extend beyond the conventional roles of lion and lamb, lover and beloved. At times, the lamb turns out to be a wolf in grown up lamb’s clothing.