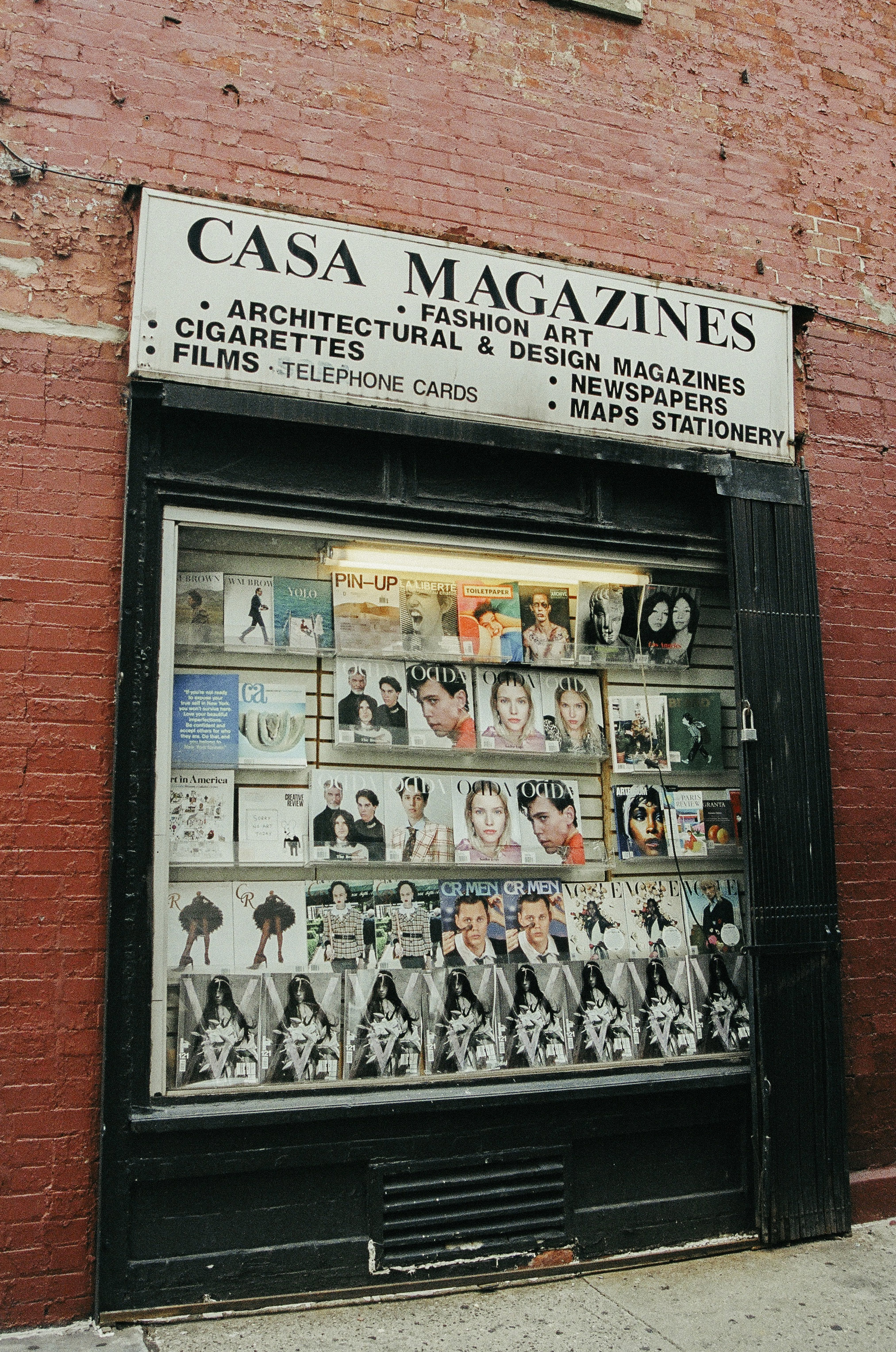

Long Live Casa Magazines

His bond with Ahmed has become so integral to the newsstand’s identity, so much so that they’re often mistaken as blood brothers. In his early years at the newsstand, business was booming: Print was the most accessible way to read the news and find job and apartment listings, and hundreds would line up outside the West Village storefront on Saturday nights to get their hands on the Sunday New York Times.

But fearing for the future of print has long been the nature of the business for the pair. In 2008, the financial crisis stood to change the industry indefinitely, and print magazines began departing Casa’s stands as publications went digital. Now Covid-19, which has already hit publishing hard, is impacting critical factors like foot traffic and international shipments and poses a grave, unprecedented threat: “The weak will get weaker,” MediaVillage analyst Jack Myers said in March, shortly after the first Covid-19 case was reported in New York. Up until recently, Casa has been utilizing Instagram, GoFundMe, and alliances with other local businesses to stay afloat ahead of the city’s June 9th “Phase 1” of reopening. “Everything is getting worse—we’re never getting good news from the business point of view,” Wasim tells me.

When I visited Wasim late last year, Casa Magazines, no more than 400 square feet in space, was bustling with tourists and locals. “Where’s the New Yorker?” one patron called from the front. Recalling from memory, Wasim motioned toward the latest issue with a laser pointer—he tells me he knows where everything is, from memory. Over the course of two hours, I met dozens of customers Wasim knew by name, and pieced together his story; what brought him to the magazine business, and Casa, and what made him stay. At one point, I asked him what another media industry crisis would mean for his profession, a question that now feels like an unfortunate premonition.

He shrugged: “Look at the whole world—one day you’re gonna die, you know? Nothing is forever.” Coronavirus hasn’t deterred Wasim—he’s still in the store working most days, and continues Casa’s Instagram tradition, donning a mask as he advertises new titles.

“I fell into this business, but I love what I do,” he said. “And I’ve never wanted anything different.”

Below, Wasim opens up to office about his work, his personal life, and what it's like to be sustaining one of New York City's treasures in a time like this.

I’ve been working at Casa Magazines for 15, maybe 16 years. My job isn’t easy—sometimes I have 40 bundles to display, sometimes I have like 80 bundles. We carry almost 3,000 titles. I have to remember exactly where everything is, from memory—months, titles, issues, they’re all in my head. And it’s all in this small space. If we were just a little bigger, we could probably hold something like 10,000. But our customers have supported us, consistently, for years. I’ve met so many educated people in this business: Designers, actors, directors—I’ve even made friends with people like Liv Tyler, and Sarah Jessica Parker … Julianne Moore, she’s my best friend, you know [laughs]. But now that there’s coronavirus, the city is empty—there are no locals, and no tourists, and our international shipments have stopped. And that means no magazine sales.

Even beyond that, things have been changing here in the West Village, for a while—for the longest time, our main clientele was members of the gay community. Over the years, they’ve been pushed out, but some of the people who don’t live here anymore still make a trip down to see us. The way technology has advanced, it’s changing things, too. At one point, we were cash only. Now most people want to pay with their credit cards. Will people completely stop using cash in five or ten years? We’re talking about paper—so I think in five or ten years, magazines might be completely digital, too. But when people walk into a magazine store, there’s a distinct smell, and that smell of paper and print makes people take a deep breath, and feel happy. When they have something physical in their hands, they feel something different. I hang on to the fact that what makes print unique might be what helps save it.

This business is all I know. I got my start in New York in a basement apartment in Corona, Queens with my three brothers. I was only a teenager, so I couldn’t find work. I didn’t know English, I didn't know what anyone was talking about, I didn’t know what was even going on in my own life, for the first three years. When I turned 18, I went looking for a job. I wasn’t educated, didn’t have skills to become a handyman or something. By then I could speak and understand a little bit of English. Even though I will never be able to speak English as well as an American, I’ve never been shy about speaking it despite it not being my own language. I applied to different retail jobs until I got my first magazine stand job on 1st Avenue and 63rd. I’ve worked at magazine stands across the city since.

In a lot of ways, New York is all I know in America, too. The one time in my life I went somewhere else, it was San Francisco, some 20 years ago. It was okay for a few months, and then after that, I just got bored. New York City is the city that never sleeps for seven days a week, right? In New York, when you feel depressed, you can go to Times Square, you can just go to the Madison Square Garden here, there, and you can take everything in.

Growing up, I was a troublemaker. I got into street fighting. You see my height, and my build, right? So people would come up to me and say, "King come, we gotta go beat somebody.” I went along with it. My father was the Education Director of Karachi. People started to ask him, "Hey, what is your son doing?” My parents thought I was turning rotten, so they sent me and my two siblings—we’re like the Three Musketeers—to the United States for punishment. If there’s one thing that I’ve learned, that has been very important, in all my years of life, is that I never lie. I believe in karma. I know myself, and since I was born, I’ve never lied. I will never lie, even if I suffer for it.

Everything in this world is not for everyone—and I feel like for me, it’s too late to pursue my lifelong passion of photography. America isn’t like back home, where you can hang around someone, and learn from them, and become a professional in something after a few years. Everything in this country requires education: If you wanna be a plumber, you gotta go to school, if you wanna become an electrician, you gotta go school. I’m bad at English, I don’t have a high school diploma, so I can’t go to school for photography. But that doesn’t stop me from taking pictures of things that I see with my phone, or being inspired by the things I see in every magazine we receive here in the shop, every day.

All my parents really wanted for me was for me to not be a troublemaker. In Pakistan, you’re told what to become—but in America, you get to choose your dreams. That’s what I want to pass down to my kids. I want them to shape their own futures.