Love Thy Neighbor

Stay informed on our latest news!

Her debut solo museum exhibition “Surrogate Selves” opened last December at the ICA Miami, merely the latest in a string of solo and group exhibitions she has participated in since graduating from the Rhode Island School of Design in 2020. Few other artists of her generation have managed to achieve what Gordon has, much less so quickly. “People really relate to the paintings,” Gordon says of her success, looking a little dumbfounded. “And, honestly, it's kind of bizarre to me.”

Raised in Somers, New York by a Korean mother and Jewish Polish-American father, Gordon often felt like she didn’t belong in the community around her. “I felt very isolated,” she describes. Finding solace in a series of creative pursuits from crocheting to sewing to fashion design, Gordon would eventually find herself driven by what she calls a “subconscious curiosity” about the medium of paint. By the time she entered high school, she had started to develop a level of technical skill and precision far beyond her years. As she honed her craft at RISD, her works began to catch the eyes of professors and collectors.

Gordon’s singularity lies in the visual language she has been able to develop for herself. In an age where we are all subject to a constant and overwhelming barrage of imagery, Gordon has been able to stand out from the noise. Whether one is familiar with Sasha Gordon's work or not, one can recognize the common language between her paintings the same way one can hear a foreign language and recognize it without speaking it. According to Gordon, she developed that language for herself as she left her hometown and grew into her own independence and selfhood. “I think I was really basing my paintings on how much skill I had,” she says of her earlier work. “In the past few years, I used the skills to translate storytelling and narrative and feeling. I had some great professors [at RISD], and a lot of them were telling me to be looser. I’m a very uptight detailed person and I still am. There’s a way of keeping that but still inventing something new, rather than painting something as realistically or as close to the reference image as possible. There's so much you can do with paint. It’s limitless.”

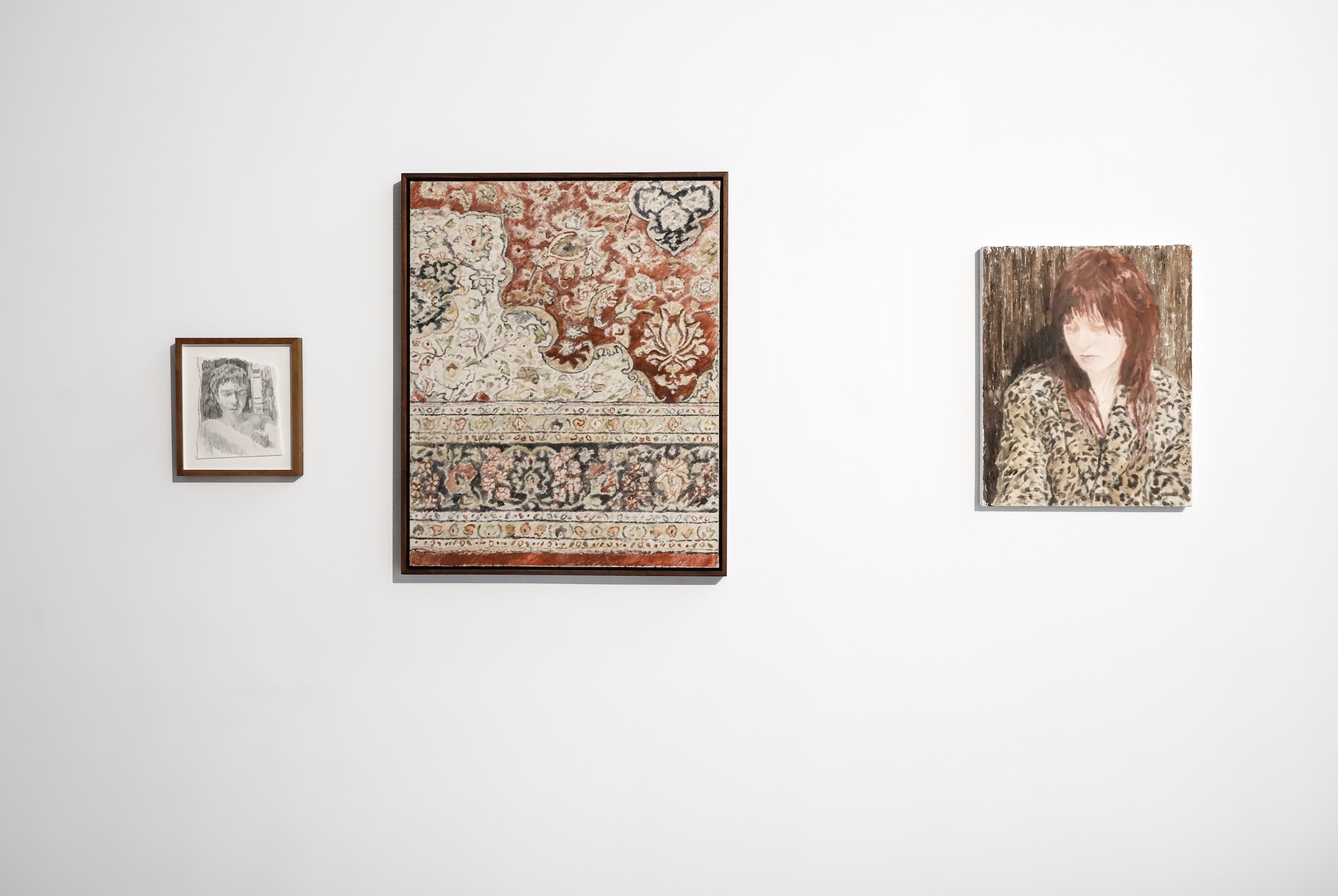

'Something We Said', 2024 'Untitled', 2024

But more compellingly than their technical perfection, Gordon’s paintings are able to evoke the inarticulable and constant discomforts of daily life, emotion, and interaction. “The work is really earnest,” she says, “and that’s because I put whatever I'm thinking out there. I can’t think too much about who’s viewing it.” The effect of her paintings is inextricable from the sense that one gets that Gordon is still painting as though she is alone in her room in Somers, New York. Now that she has had some distance from her childhood, Gordon says she is able to enjoy the scenic nature of her hometown when she visits. “It definitely makes me appreciate my life now a lot more, just because of how alienated I felt growing up,” Gordon says. “I really value my community here [in New York City], and my artist friends.”

One such artist friend is fellow painter Amanda Ba (b.1998). Both born on the cusp of generation Z and part of what Ba refers to as a “small network” of Asian American figurative painters in New York, Gordon and Ba became close in the last few years but have known of one another through social media for much longer. Ba’s studio is in the same building as Gordon’s, and the proximity of their workspaces allows for hang-outs and informal studio visits with a rare level of frequency.

When Ba walks into the room, she immediately takes note of the plant cutting on the coffee table. “The Pothos grew!” she says, settling into a chair across from Gordon. For the next hour, the two painters trade nuggets of wisdom as they pass yellow American Spirits and a bowl of strawberries between them. We discuss the machinations of the art industry, the influence of their hometowns on their art practices, outsmarting identity politics, and so much more. Read our conversation with Sasha Gordon and Amanda Ba below.

How did you two meet? Did you encounter one another’s work before meeting?

Sasha Gordon— I found you [on Instagram] around the end of high school. One of my old friends showed me Amanda’s work, like “Oh, I think you’d like this girl’s art.”

Amanda Ba— I definitely saw your work online before I ever met you in real life.

SG— In high school, I wasn't familiar with any Asian artists, or any artists of color. Then in college, I did my research, and I saw some established artists that dabbled in really similar stuff as me. But seeing someone my age was just really important; we're both coming up in this kind of confusing art industry and world. And I thought she was so talented.

We didn't meet [in real life] until, like, three or four years ago, because we were both in college.

AB— Yeah. And we were always friendly, it was just sort of this distant observation until we met and got closer.

Before showing in a gallery, I didn’t really have a very concrete sense of how things in the art world operate. I painted progressively more as I got more into my major requirements towards the end of college. I think we were both experimenting with a lot of different styles.

SG— Yeah, we don't paint the same way as we did then. Not at all.

AB— No, not at all. But yeah, I mean, it was sick to see someone doing really well, whose work I identify with. And it was good motivation. Not necessarily competitively, but just motivation; you see someone else's work that you really like, and you're like, oh, I wanna do better.

I think that as we grew up, entering the art world, or just becoming more familiar with it, it became more important to actually make note of other artists’ work. When it comes to Asian figurative painters in New York, we probably know most of them either peripherally or we’re friends with them. It's just a small-ish network.

You both had this experience of entering the art world — to use your word, Sasha, the art industry — at quite a young age, and have experienced a rise in visibility for your work rather quickly. But you’re also both still young, and still growing up. Typically the art is thought to reflect life, but how much do you think the forces of the art industry are also influencing your lives? How much does that then show up again in the work?

SG— I don’t think anyone’s ever asked me this before. I feel like [the influence of the art industry] is pretty constant. I'm having at least a few studio visits a month, and talking to other artists, and seeing galleries, and I try to stay up to date with other painters. And then there’s art fairs.

AB— The fairs are the only thing that resembles an office or work environment.

SG— Yeah, it’s really bizarre not having a set schedule. The art fairs do kind of make a replacement for that, the fairs are when you become social. Otherwise, it’s quite an isolated job.

AB— Scheduling in the art world definitely dictates the pacing and the work-life balance of your year. And for example, my show is set up to coincide with the beginning of the art world season in the fall, and art fairs like [the] Armory Show…

SG— Frieze too, there’s a bunch of art fairs. That’s so true.

AB— And they all happen around the same time as fashion week. If anything, actually, the broader world is always on a school schedule. Everything starts in September.

What about its impact on the pace of your production?

SG— I feel like there hasn't been one show where I’ve had extra work, or finished on time. Almost every due date I've had, I've pushed by at least a week or two.

AB— It’s on us to agree to the deadlines; we decide how much of a workload we can manage within a very long time. And it's bizarre to think about a project that could be a year or more away, and how you're going to keep yourself paced during that time. But there’s nothing else dictating our work time.

If we had time to just chill with paintings and experiment with no deadline — I actually have no conception of what that might be like.

SG— Right. It's so weird also, because you never know how long something is going to take. So I feel like you sometimes have to grind just to be safe.

[The pacing] definitely helps me, personally. I think it pushes me to work in a different way than I'm used to, and I learn a lot from that. I can get super obsessive, and if I didn't have a deadline, I could probably work on one painting for eight months.

Now, I've gotten way more accustomed to the schedule of things, and there are some moments to be expected where the end result might not be exactly how I pictured it.

In the last several years, there has been a massive uptick in fascination and interest with “artists of color” and “marginalized” artists, which has also been coupled with a very exploitative model within the art world that can reduce people to just their marginalized identity. How are you thinking about navigating that in your work now?

SG— I remember a professor I had, who is a Black queer painter, and we were talking about this topic. She was saying that she paints Black figures, but she doesn't feel like she needs to explain it or go into such detail about it, because she just exists as that.

That really struck me, because I was doing more work about identity a few years ago, when I was discovering a lot about myself and was reflecting on my whole childhood experience of growing up in a white community. I think it was important for me to make those paintings, I definitely go back to those paintings a lot, and sometimes I find the paintings I'm working on currently have more to do with identity. But I don't feel like I need to talk about it in every interview or every artist talk.

I think the paintings have more to do with the psychological effects of that experience, not so much being Asian or [asserting] that representation is so important.

AB— I love talking about this topic. I think that what your professor is getting at is, why aren't we ever questioning paintings of white people? Why is it not shocking to paint them? It's a given, it’s not a big deal, and therefore it's omnipresent, but it's not the focal point, right? It's just part of the experience, part of a continuum.

SG— If you paint an Asian person, it’s like, “look at this Asian American painter Amanda Ba!” But would you ever say, “look at this white painter?” because someone painted white subjects?

AB— The natural, intuitive motion is to insert people that look like us into the canon. The goal isn't to, like, recognize Asian people. The goal is to have images of people of color be treated as commonplace.

I don't know if we'll ever get to this point, but if there was a more adequate sense of representation, maybe we would then have the freedom to go and, like, become minimalist sculptors or something.

SG— That would be awesome. [Laughs] I mean, it's cool sometimes when I see artists who don't have any take on identity, and just make beautiful images. That must be nice, to not have these ideas assumed and placed on the work in the way that it happens to us.

AB— It's also about how much responsibility you feel and want to take on, and then want to project out into the world. We totally have every right and reason to say fuck all, and make work that’s maybe even devoid of figures. But I think it's also about complicating identity to a point where it's less easy to explain. You can't just indulge yourself in your own intentions or whatever; you have to be aware of what is always out there.

So how do I outsmart that in some way? Can I make the painting so complicated that they have to think about something else?

You both grew up in places that were not major cities or considered hubs for art, and I’m curious how you think that affected the development of your practice. Had you grown up in New York City, do you think your practice would be different?

AB— I have no idea what it would be like to grow up as a teen in New York. That really perplexes me.

SG— I heard there's almost too much freedom. I can't imagine. I was so sheltered and had very limited resources compared to what I have now living here. I feel like… maybe I wouldn’t have painted?

AB— You might have just been having fun, partying.

SG— I also think being sheltered definitely made me. I had to learn a lot on my own. I didn't have access to what I wanted, which was more of an art scene. So I kind of had to do my own research by myself, and really spend a lot of time practicing the craft and building up that level of skill.

And if I didn't have that transition, from growing up upstate to moving to Rhode Island and then the city, I don't know if I would have come to all these solutions and conclusions of my experiences and my identity. Making this more narrative work — I don't know if that would have happened.

Do you ever have informal critiques with each other?

AB— Every time we see each other is a little bit of an informal crit.

SG— Sometimes I need a second opinion. I don't always take the advice, but I like to hear it. I definitely value what Amanda thinks of my work, so I want to hear her take on things.

AB— Yeah, same. I feel like sometimes I come to you and just ask, like, “what color?”

SG— We'll show each other like artists we like. We're constantly looking at Lisa Yuskavage’s work together — you can tell when we were starting a painting, and we pulled up Lisa’s website.

AB— Painting, at least the way we paint, is harder to critique and then go back in and change something drastic. But we are catching each other at stages where there’s actually a decision tree, a fork in the road: this way or that way.

SG— In college, critiques were our main way to get to talk about the work and run ideas through people. It was an adjustment to move to the city during COVID and not have anyone see my work or get to talk about it. And it's nice to have studio visits, to be in the same building with Amanda — we call it school, it almost feels like camp or something.

AB— We hang out as friends, but if we're hanging out in our studios, the work is always peripheral. You know, I think your studio is the only other studio I see so consistently, like multiple times a week, steps and steps of progress, talking to each other about color palettes, and compositions.

SG— Yeah, it's really nice. We can visit each other and it makes us realize there's like a bigger world out there than just our studios.

AB— Friendly competition is so helpful to me, too. It's just like, wow, this person made something amazing, and I want to make something better. The speed of the art world makes you feel this way, but it's not this limited set of ranked spots. The goal should be to expand. When I see someone make a really great painting, I'm like, fuck, I wanna go back and make a really great painting.

SG— I remember we were talking once about some artist, and we were both, like, almost jealous of them. We were really critical of their work, but I think it's because we were so moved by their skill and technique. It's so cool to like, keep in touch with all these people, and see what they're up to — to motivate each other with each other.

Sasha, a while ago, you said that you were curious to see what the work would look like if you weren't showing. Have you had a long enough period to actually get to see that? If you did, how do you feel that the work has changed?

SG— I don't think I have. There was the first show I had, I had like a year and a half, and that was actually kind of challenging. It was during COVID, so pretty much no outside opinions, or advice. Recently, it's been like I’ll have a show and then I’ll have 5-7 months ‘til the next, and I don’t really have time to… I think I said I wanted to make “ugly” paintings.

AB— What about this one? I feel like this is the only one. [Points to a painting on the wall]

SG— That’s true, this is the only one I did because I was a month into dating my partner and it was a present. And that was fun! I feel like it's looser and smaller and there's no expectation.

I constantly want to make better work, and I feel like I've set up a certain standard for all my paintings having insane detail and huge scale and new innovative ideas. It has been hard to do, but every now and then I get a chance to try to make something weird. I don't have to show it or display it, I just keep them. I definitely want at some point to have a full year to just make stuff with no goal of showing any of it.

I actually will be going to Italy in October for a residency, so hopefully I can do some more exploration then. I went to Rome once to study abroad, and I also changed a lot during that period. I think being away from the city, and other artists and friends, it just inspires this freedom to fuck around.

So tell me about this pilgrimage you’re going on.

Ten years ago, I first read Anne Carson's essay “Kinds of Water,” which is her account of walking the Camino de Santiago. I’d say that this piece of writing has most influenced my own, as well as the ways I think about research and citation. So the pilgrimage to Compostela is something that I’ve held in my mind for years as a poetic abstract, and this year took on as a tangible act. My life felt aligned for it. Anne Carson did her pilgrimage with a man she loved who did not love her back, while she was dealing with the slow loss of her father to dementia. I am doing my pilgrimage with my best friend of ten years, while trying to take stock of my triumphs and losses as an artist, lover, friend, offspring, and addict.

A pilgrimage is a spiritual thing, but it is also just a thing to do. The undertaking is formidable but straightforward. I like this as an expression of faith. I grew up in a secular home; my parents did not grow up with organized religion because they were in Communist China. So my limited exposure to religious practice was more social and textural. For instance, in China where I spent summers as a child, as our weekend activity we went up the mountain to the temples where we lit incense and prayed for wealth, abundance, and good health. Beyond that, I was not familiar with any kind of devotional or spiritual practice. Growing up in the US, going to public school in the suburbs, I vaguely understood that some people went to church or synagogue on the weekends. It was not until I was in second grade that I learned that Christmas — which I understood only to signal time off from school and a conifer in the foyer — was a religious holiday that had to do with something called Jesus.

In my young adulthood, studying Western art history, I learned about the Bible and the Church. Those stories about saints and the material manifestations of Catholic belief — the sensual, erotic ritual of them — interested me. I think that arose from both my interest in Anne Carson, who is a very spiritual writer, but also the period of my early twenties where I was working a lot with Chinese mythology and thinking about the impulses behind the creation of these belief systems. They were ways of lending structure to overwhelming longing and fear. While I could not necessarily understand a literal belief in God or the cruelties of organized religion, I could understand intense, transportive desire, and the ecstasies of self-flagellation and martyrdom. So now, perhaps in an attempt to apprehend something I am not yet aware is within me, I choose to walk the Camino.

It’s interesting hearing you speak about Catholicism from this perspective — removed enough to recognize its aesthetic and symbolic meanings and its relation to desire. It reminds me of this one line in Carson’s “The Truth About God”: "My religion makes no sense and does not help me. Therefore, I pursue it. When we see how simple it would have been, we will trash ourselves." Are desire and suffering all that different if one can lead to the other? Is it the pursuit of a thing that gives meaning? There’s the line in the press release about your show: "I have never felt guilt, but I have felt the suffering of others."

Is suffering a central tenet of Trick and what does that mean in your practice more generally?

Maybe not so much suffering in itself, but equivocation and simultaneity. Rapture and pleasure are inextricable from suffering and horror; it's about extremity, it's about intensity.

Trick reminds me of the use of irony in Anne Carson's work in that she's revealing how these different feelings, as you described them, can be superimposed among other structures. Do you think about irony?

In its popular deployment as facetiousness, I detest irony. I find it cowardly and bullyish. However, when it comes to irony in its literary applications, there is a lot to be said for slipperiness and foiled expectation.

My sense of humor is dry, and maybe that is where it coincides with a writer like Anne Carson, who is also ironic and dry. I've been told, and I probably agree, that I speak in a monotone and that my affect is very deadpan. I think the prevailing tone in my work is also one where things are as they occur. I try not to make things too atmospheric in the way that some cinema manipulates emotion or affect with formulaic editing and scoring. I try to keep the work in a space of restraint and strangeness. And I think — without trying to prescribe the term irony in ways that don't fit — in thinking about what I disclose and withhold about the work’s origin and associations, I'm always trying to make decisions that maximize the work's autonomy.

How do you know when you’ve achieved that?

It’s about stopping before foreclosing possibility — when I know that there remain a hundred other things I could still do to a piece. I want to stop before the point where my interventions start preventing the piece from acting in and of itself. As for how I decide where that terminal point is, that comes with practice and intuition. I'm always trying to work just a little beyond my existing skill set. So there is also the condition of where I reach my physical or technical limit, which also determines where I stop.

What does this intuition feel like — especially as it concerns the pieces you finalized while setting up the show?

It's agonizing every time. I think a lot about resourcing and not wanting to waste things before they're ready. So even when I was deciding what objects, artifacts, and hand-sculpted elements I wanted to put in this show or any of the group shows leading up to it, I was balancing my resources and trying to be strategic because I don't want to use a carved wooden limb or an expensive display case for a piece too early and then realize, Oh, I wanted to save it for this other situation. I think that is part of the reason that I work very slowly.

I grew up in the home of an immigrant hoarder. We saved everything, and we did not organize the things we saved. Our house was enveloped in urgency and paranoia. It takes wealth to be able to throw things away; you have to know that you can replace them. So I moved through the world carried by this undercurrent of scarcity. But I think that also allows me to recognize the agency and majesty of everything that I make or collect, because once I bring it into my fold, then I am responsible for handling it with great purpose.

In the studio, I do a lot of Tetris. With the piece Heads, that has the scythes inside the display case — I think I tried out at least ten different objects or situations in the display case before I knew it would be the scythes. And each of these ten possibilities lived inside the case for weeks. It was probably only two months before the show opened that I manically ordered all these scythes on eBay. I don't even remember why, maybe I read something about them, saw them in a film, encountered them in a dream. Suddenly I had all these scythes, and I thought I was going to use them in a different sculpture, but then I ended up storing them in the display case because there wasn't any other room in my studio at the time. And I realized that that was where they had to live. And the papier mache figure that’s mounted sideways on the wooden pedestal in that piece, I originally made that figure to sit on top of the expanded steel structure in Trick, the video piece. But once I had the steel object in the studio and saw the figure on top of it, I realized that my original idea doesn't work, it doesn't serve both objects. They're being wasted in this configuration. So you keep trying other permutations.

Catalina Ouyang Untitled, 2024

A favorite of mine is this amorphous, dog-like piece bound to the high heel. Can you tell me about the thought process behind that one?

That piece originally began as two separate works. The dog with the long leg on the cart was originally part of a much larger piece that was built around a found auto part that I draped in a resin-soaked piece of fabric. It was a seven-foot-tall sculpture, over eight feet long, and once we delivered it to the gallery, I realized there was not enough space for it. I cut the large sculpture from the show, but I knew that the dog with the long leg and the high heel had to stay. So I thought, Let me amputate that element from the existing work.

The painting verso featured in the final work was originally a standalone piece with a legible image painted on a piece of shellacked gauze stretched over the wooden support from a pet staircase. The original reference image for the painting is of me and a friend frolicking naked in a waterfall, like nymphs. One day in the studio, I had that painting propped backward against the wall, and I thought, That is a much more interesting image. So let me present it that way. Then, suddenly during install I had this dog element excerpted from the larger piece, and I realized that, subconsciously or coincidentally, I had stained the wood of the dog almost the same color as the pet staircase in the painting version. So they ended up in the work together. When I’m in the chaos of the studio, even when I don’t realize it at the moment, all of these things are visually and haptically feeding into each other.

So, almost like putting together the pieces of a puzzle, with pieces that can fit in multiple places.

Yes, and while I can be decisive and spontaneous with these last-minute decisions, they are still intentional. I think about the ways that writers or poets reorder their lines on flashcards, it’s like that. I made everything with sincerity and urgency, so I have the freedom to rearrange those things and have the result be, if not didactic or legible, intentional.

Writers like Carson and Clarissa Pinkola Estés who we spoke about a bit during the walkthrough bring to the present very primordial ideas having to do with the divine feminine, and making sense of these ideas in a modern context. Would you say you’re attempting something similar with your work?

I like rule-breaking not for the sake of rule-breaking, but rule-breaking that emerges from a true kind of self-knowledge. I think that has to do with spiritual immanence in which you feel connected to some kind of truth. Or where you feel truly connected to the unknown. Women Who Run With the Wolves is interesting because on the one hand, the book saved my life at a time when I was young, angry, and almost indescribably hurt. I was on fire. The book’s almost utopian framing of empowerment and, as you said, the divine feminine, did have a meaningful impact for me then. But on the other hand, the text upholds gender essentialist and overly affirmational tropes about femininity in ways that I find less compelling. I am more drawn to the long tradition of melancholic, almost sickly white woman writers like Marguerite Duras and Jean Rhys and, perhaps more contemporaneously, Ariana Reines and Anne Boyer, who write with a kind of spikiness and unbridled anger that really courts conflict — not purely as an impotent mirror to the sufferings of the world, but as a mad grasp for transformation that finds gratification but does not pretend to find resolution.

Yeah, you see that very clearly in Rhys’ Wide Sargasso Sea. This unbridled anger that bleeds into her story from the other book somehow reminds me of what you tried to do with Brank, the reimagined scold’s bridle, a tool of suppression transformed to one of voice, and housing a poetry reading series on the opening night.

With influence, we take from ancestors that we either choose or are delivered to us, and these ancestors cannot be sanitized. They’re sexist, they're racist, they're rapists, they're abusive, etcetera. Monumental sculpture in itself carries a macho connotation of taking up space, deploying certain kinds of weight and rigidity. Brank is laden with these signifiers at the same time as the piece itself is a transgressive space of active congregation. There was a time when I felt opposed in my practice to reifying the very things that I was critiquing, and that was when I veered most toward the toothlessly affirmational. But I think now I'm much more interested in letting evil exist with its own volition, and refraining from placing my judgment or projection upon the form or feeling of evil, badness, or pain.

Catalina Ouyang Brank, 2024

True recuperation is also impossible. It was maybe 10 years ago that we suffered through that trend of revisionist Hollywood films like Maleficent with Angelina Jolie, Snow White and the Huntsman with Kristen Stewart, and other stories that tried to instate humanizing origin stories for classic villains and peripheral characters. That was something that I was once interested in in my work as well — the humanity and motivation of historically vilified women or Othered and queer characters. But in hindsight, I find that even in those revisionist narratives, the villain is sanitized into a misunderstood being of kind, good, or justified intention, and I'm more interested in, as we've been talking about, the miasma that exceeds morality or redemption. More like Angela Carter.

Even the desires that are foundational to our living drive — of accumulation, maintenance, and community building — are necessarily concurrent with the impulses of the death drive, which include pleasure, compulsion, individuality, and libidinal fixation. You have to find a way for them to coexist, which I think is what I am always trying to be attentive to in the signposts that I create with decontextualized references to historical figures, poems, and myths. My intention specifically is not to explain the gaps between them and rather to let them be generative in their unruly junctures.

How do the living and death drives show up in your work?

I think contradiction remains the word. With my invocation of the famous artist and courtesan Sarah Bernhardt, I am trying to address the act of selling sex as both an empowering, liberating mode of making a living, and also a survival industry that has trapped, extracted from, and killed many providers. Sarah Bernhardt is an iconic example of someone for whom it allegedly worked out. But there's also a lot of antagonism in my relationship to that kind of work and value-making. Part of my impulse to show paintings in this exhibition reflects how I feel similarly in some ways about painting as I do about my sexuality; it is this asset I possess that can be deployed toward some kind of value exchange that is efficient, but is in conflict with the fact that I want to make objects, I want to make conceptual work. I want to share my life with a lover and be loved without the raw threat of my sexuality and line of work getting in the way.

There are things that painting takes for granted — the picture plane, materiality, a painting’s objecthood or lack thereof — that I take issue with. There are things that my commodification as a sexual being takes for granted, that I most certainly take issue with. There are concessions at play, but still I am intent on engaging with the practices of making paintings and selling sex in honest, risk-taking, and challenging ways. So it's about going into the thing that already feels doomed, but finding some kind of return in it.

Do you think about "goodness"?

No. Sometimes I hear from other people that they're concerned about being a good person, and I roll my eyes. I don't know what that means, “good person,” because you either do things that are not harmful to other people and you act with compassion and accountability, or you don't.

Protestant ideals often equate "goodness" with diligence and labor. In contrast, your work seems to challenge these structures by granting autonomy to your creations. How does this perspective shape the narratives you build?

It has always interested me because of how Protestant ideals often equate "goodness" with diligence and labor. In contrast, your work seems to challenge this by granting autonomy to your creations.

For my whole life, I have been characterized by others as cynical and pessimistic. Which is silly, because I would not have continued making art all these years if I were a pessimist. With every project that leaves me in debt, that doesn't get the recognition I hoped for or even expected, or simply is an artistic failure — I have to be basically stupid with optimism that the next time will work out better, that I will get closer to the truth. And every time, I am optimistic.

The painting Deed is based on stills from the Catherine Breillat film Anatomy of Hell. On the surface, this is a morally confused, nihilistic film. You have Rocco Siffredi, the Italian Stallion, playing a gay man who gets entangled with a suicidal straight woman. And the film seems to be proposing, however problematically, that his having this heterosexual psychodynamic encounter brings him to some kind of salvation. In the end, he pushes her off a cliff and it ends in this violent rupture — is it refusal, pure negation?

Nobody is saved, but something unpinnable is exchanged and transformed between these two characters. In order to create anything, you need to believe that you can move mountains with all the wrong tools and the most ambiguous intentions. Diving into the mess and expecting to reemerge with a revelation — it is hubristic, and it is also a beautiful act of faith.

Today, nearly forty years later, the ephemeral StillShow presents artworks that confront computerized conditions as real, lived experiences rather than abstract concepts. While philosophical discussions may be notably absent, the pop-up exhibition, housed at the iconic 54 Crosby Street — once the studio of Charging Bull sculptor Arturo di Modica — offers a tangible engagement with these themes.

This curation, centered around posthumanist anxieties of disembodiment and technology, is recontextualized in downtown New York. Featuring many of the city’s art scene darlings, with a focus on Asian artists such as Ren Light Pan, Xingzi Gu, Lorenzo Amos, Abed Elmajid Shalabi, Yasmin Anlan Huang, and Naoki Sutter-Shudo, the show transforms the irregular layout of the four-story building into a treasure hunt of artworks amidst a backdrop of fashionable melancholia. The dimly lit space, enhanced by architectural skylights, invites close inspection by viewers.

Following her debut solo presentation at Lubov Gallery in Chinatown, Xingzi Gu presented two works in the show. On the first floor, visitors encountered Gu’s painting Untitled (Sunday Fiction), 2023, featuring a loosely drawn girl gazing up against a dreamy pastel background. Gu replaces traditional calligraphic scripts with playful pencil doodles, creating an unlikely poetic charm with a touch of spontaneous sensuality. Nearby, Untitled (Companion), 2023, is displayed in the second-tier passage next to Stephen Deffet’s Worlds in between/purification, 2024. Gu’s folk-inspired work quietly complements Deffet’s abstract panels, arranged on jigsaw playmats.

On the second floor, one of the “blind boxes” in the show features Tianyi Sun’s Store in a cool dry place (下午), 2024. Modeled after a dim sum cart, the piece invites interaction on multiple levels — physical, metaphorical and material. From afar, a light mist emanates from its intricate interior, which, upon closer inspection, is infused with Goji Berries and Ginseng for facial hydration. Mooncakes, molded with jujube in purple or transparent silicon, are displayed behind informational plexiglass. Sun’s work distills the disembodiment of experience into a selection of dispersive and participatory elements, regurgitating fragments of personal memories and history.

All of the works, through their different material state of being, convey a harmonious presentation of transience, ephemerality, instability, despite stylistic overlap. A pleasant surprise can also be found in the basement: Sizhu Li’s site-specific installation Pushing Hand, 2024, where aluminum sheets are suspended and draped over wooden structures, creating glistening ripples that flicker under electric fans.

While pop-up art shows remain an untapped model in the industry, this showroom-encoded, warehouse exhibition space ensured a unique corner for each visitor to explore. Credits are due to the bold individuals behind Stilllife, who are bridging the art community on an international scale. “With our current society, the missing tools for open communication is a pressing issue that I think art, especially a next-generation of artists and organizations, is uniquely adept at turning into an opportunity,” Jeffrey Liu, one of the founding members, tells office. “While the Western art world maintains a dominant voice due to its history, we aim to build a unique diasporic art world ecosystem with the growth of international East Asian trendsetters.”

Supporting this artist-driven curatorial ephemera is an expansive network of creative collaborations, such as the TikTok-viral Dragon Fest, which will partner for the upcoming StillShop. “This will be our first outdoor street art market. We are hoping to present a grand summer festival blending food, art, and lifestyle, right on our ‘quad’ at Washington Square Park North,” says Katerina Wang, NYU Alum and main stagehand for Stilllife’s cross-industry ventures.

Looking ahead, Stilllife is set to launch a fall group show in conjunction with the West Bund Art Fair and Art021. “We plan to bring a bit of New York to Shanghai with a 10-day exhibition and programming that aims to engage 10,000 art communities, artists, and collectors from around the world,” shares Azure Zhou. Sign up to the Stilllife newsletter here.