Miu Miu M/Marbles

The Miu Miu M/Marbles Stool is available for purchase exclusively at the Miu Miu Miami Design District boutique and miumiu.com.

Stay informed on our latest news!

The Miu Miu M/Marbles Stool is available for purchase exclusively at the Miu Miu Miami Design District boutique and miumiu.com.

Barsky and Planit’s goal is not to completely alter the art world from the inside out — they recognize how it has molded and shaped them into the people they are today. Rather, they intend to take the art universe and make it a little cozier, inviting artists of all backgrounds and tenures into comfortable spaces where they feel accepted and encouraged to speak — or paint, or sculpt, or collage — from their unique perspectives.

office sat down with the creatives behind the platform to discuss demystifying the art world, how artists can best support each other, and more.

What led you on this journey? Haylee, how did you end up teaming up with Blayne to get where you are now?

Haylee: I initially started this project in January of 2018, so I'm celebrating my sixth anniversary. It was an idea that naturally came about as I had this little gallery space in Italy and I was always trying to figure out how to bring people together. It was right before the pandemic so it was a tough time that I had to figure out how to navigate alone — it's incredibly difficult to run something by yourself. I knew that I always wanted a partner. Then I met Blayne almost a year and a half ago. There are only very few people that you cross paths with in your life that you feel called to. I really believe in the red string theory. We met for the first time and everything that we were talking about just made sense. We didn't wanna say it to each other, but we telepathically knew that we were on the exact same page. It was the weirdest thing in the world. It was almost like we were just meant to happen and it felt supernatural. Now it feels like we're married. Without her, I wouldn't be where I am right now. It's been a wild year.

I know your current work is heavily involved in uplifting artists, but you both have connections to your own creativity. What inspires both of you day to day?

Haylee: I get inspiration from the energy of New York. It may be a stereotypical thing to say, but everybody here is just so driven. I don't think this could be done in any other city personally.

Blayne: I would consider myself a very inspired person. I find inspiration daily and even in the smallest things. I really like mornings. When it comes to furthering our visions and this community, we think about general inspiration and then inspiration concerning this project and what we're focused on growing. I think there's now inspiration that's kind of in motion. Momentum. The inspiration comes from the momentum, in a sense, watching our visions and ideas and people coming together and all the positivity that results from it. It creates this bubble of inspiration. Bringing these artists' dreams together and showcasing them in the ways we have — it's all pretty inspiring to both of us to watch that unfold.

Haylee: There's clearly a need for this in the art space because people are showing up. We also want to focus on the online network because the online platform is so global. New York is just a part of the network that we've cultivated and are actively cultivating. The artists come first and they always will. And that's how history has always been. Then the people who are inspired by them and everybody else just follows. So they're always going to come first in our mindset.

I know that you have hosted and then plan on continuing to host things in these non-traditional spaces. Why is that important to you both?

Blayne: I think ‘non-traditional’ doesn't always have to apply to the space. For us, it's more about taking what we firmly believe in, which is the power of bringing people together, and spotlighting that. I've always been really into public art and art that's more accessible. Art is a form of expression but a lot of people aren't really taught to express themselves in that way. My philosophy is that everyone is inherently creative. For us, this isn't about a trend, but it's just important for us in whatever we do. That's why I said it's not about the space, it's about creating an experience where art feels approachable, accessible, and inclusive. We're giving art different kinds of artists and giving different kinds of talent these opportunities. So I think that's what is at the forefront: creating experiences that aren't stale and that are approachable. Diversity is something we're always proud of within our community as well.

There are so many different kinds of people in New York, which is half of the reason it's so inspiring. At least in the art world, the events I was going to and certain things I was going to, I was seeing a huge lack of diversity. I would go to these events and there would be all these people that kind of looked the same and seemed the same. I'm sure they're all great people; it just, for me, felt a little like it was missing something. When we curate shows, it's super important for us to, bring in people of all different backgrounds.

Haylee: There's definitely a beauty behind demystifying the art world. We truly do not care about any other factors as long as you have the talent, the merit, and the drive. We also want to continue to bring people together — some could be very established in their careers and we connect them with somebody who this may be their very first show. Everybody truly falls under the same realm of existence in our space. So it's really fun to see all of that come together and to curate that. And we also don't come from traditional backgrounds ourselves. I come from a background in fashion and she comes from branding.

Blayne: I agree. I also want to add that we, by no means, are trying to take down the traditional art industry. We fully integrate it into what we do as well. It's just about that more non-traditional approach. We still acknowledge that there is an institution and galleries that exist.

Haylee: Right; I would say we definitely acknowledge, compliment, and celebrate the traditional art world, just through a different approach. Blayne: This non-traditional approach can also be accepted in traditional spaces and that's something we want to see more of.

I think connecting more experienced artists with younger or lesser practiced artists is the beauty of your platform. What are some of the largest barriers to entry in the art realm that you want to combat with your approach?

Haylee: I think there's not one single particular barrier of entry, but a lot of people just don't know where to start and it can be a very overwhelming space to navigate. So having public opportunities and making that as known as we possibly can with our network is important. There's only so much we can do and we have the power of being able to do. As much as everything has grown and changed in such a positive light, there's still so much work to be done. I would say for somebody who doesn't know where to start, just doing your due diligence — research and being on social media and just really understanding the landscape and cultural aspects of the art world — will help.

Blayne: I would add that how we're actually addressing that is through our membership, Tableau. We do an industry insight panel and we've curated it super intentionally. We bring really incredible, established art world professionals from different sectors of the art world in and host them in a conversation — kind of like this one. Our members and people in the community can get insight and access from the minds of people that are running the show, from the director of an art gallery, to an artist-run gallery, to a giant publishing house in Europe. So that's one method that we both felt was a realistic way to demystify.

Haylee: Community is how you get to where you need to be. So that's why we're trying to build this community more intentionally. It's very inclusive and everybody's invited.

Blayne: And even though a lot of it is about who you know, you can create that community for yourself. If you're putting yourself out there, it doesn't matter where in the world you are. There are so many different ways to approach it and we're also trying to teach people how to use those tools as well.

It sounds like the biggest thing that Tableau grants people is access. There are a lot of people who want to go after a creative endeavor and they don't do so because they don't have access to these tools or resources. So fostering these conversations and creating these spaces is powerful. I know that you two have talked a lot about connecting artists to people who can advise them along their path. But how do you think that artists can best support other artists, in a very non-competitive way, and foster a more inclusive industry?

Blayne: I see that all the time within our community. It's so cool, especially as someone who's an artist myself. Everyone has different philosophies, so I don't necessarily see other artists as competition because we're different people making different things. And if a gallery is not a fit for me, maybe it would be a fit for you. I think it comes down to mindset. I think an artist who doesn't want anything to do with other artists and sees them as competitive wouldn't be attracted to our community, perhaps. Hayley and I recognize that community isn't for everyone and it's not what everyone's looking for. But we see the power of connection.

I'm curious about some of the artists that VP works with — what really stands out to you when you see someone's work? I loved everything that was in the last exhibition, but I thought the beauty of it was that everything was so different.

Haylee: One of the bigger philosophies behind the platform is celebrating the idea of storytelling. There's so much power in what somebody has to say, not just about themselves, but about the world that we live in. Blayne and I have a very similar visual eye. We literally look at the same piece of art and have the exact same feeling.

Blayne: We've never disagreed [laughs].

Haylee: When curating, I'm personally a big fan lately of the abstract figurative movement just because I see myself in it. But a lot of people really love expressionism because it's more timeless.

What are your hopes for the platform as it grows?

Blayne: We both have agreed that we want to amplify our mission. We want to expand the community very intentionally. And we're also thinking about what events we can host to support people even more. I think there's so much opportunity to support artists and give them resources so that's what we're currently thinking about. How can we take what we've built and expand upon it? We want to help more people get started in the art world. And even artists, by the way, that are doing the thing, don't know what they're doing. I'm not saying that they're not intentional. I'm just saying there are a lot of people whom things are just happening for. And, of course, you can point to why it's happening for them, but a lot of them are figuring it out as they go. We want to host more exhibitions as well. Partnerships are going to be a really big theme in the upcoming year — so there's a lot of opportunity on the horizon.

Visionary Projects’ next event is a supper series in honor of their 2nd-year anniversary, hosting live artists who will create pieces for sale that evening, on February 24th.

SOL’s resume similarly defies facile categorization; at 19, she co-founded a feminist media company called The Meteor under the direction of former Glamour and Self editor-in-chief Cindi Lieve, for which she served as Multimedia Editor; and as a strategist, she has overseen internal research and international marketing campaigns for companies like Spotify and PBS. She has directed, edited and been featured by publications such as Teen Vogue, Audible, TED, Harper’s Bazaar, and The Hollywood Reporter, and her lectures and writings often channel her personal experiences as a Black woman and a political organizer.

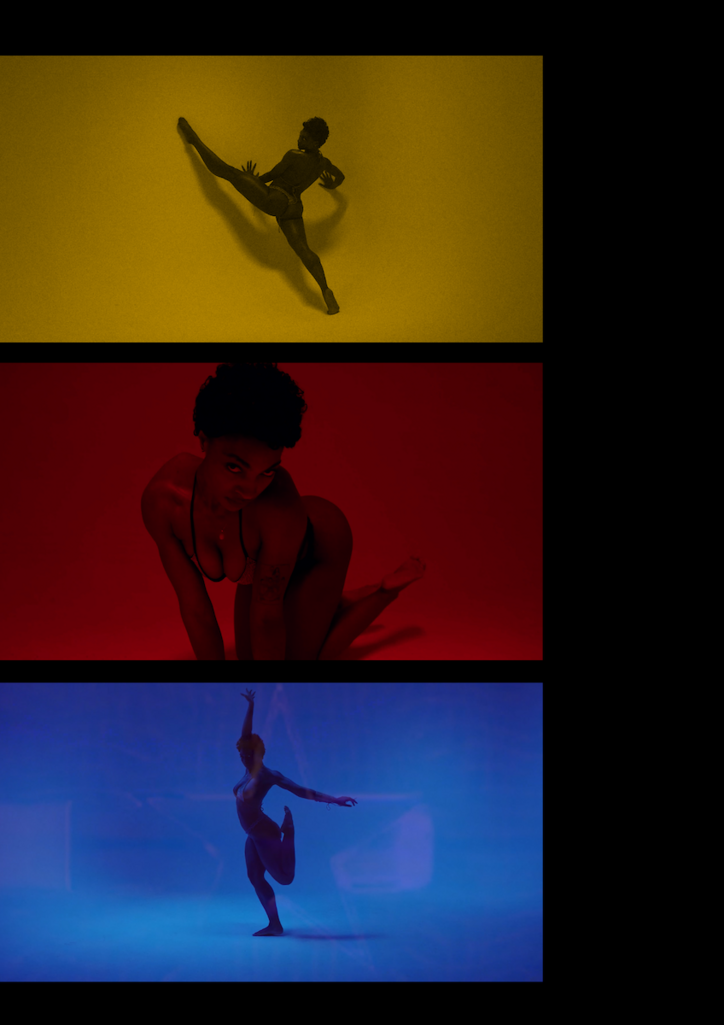

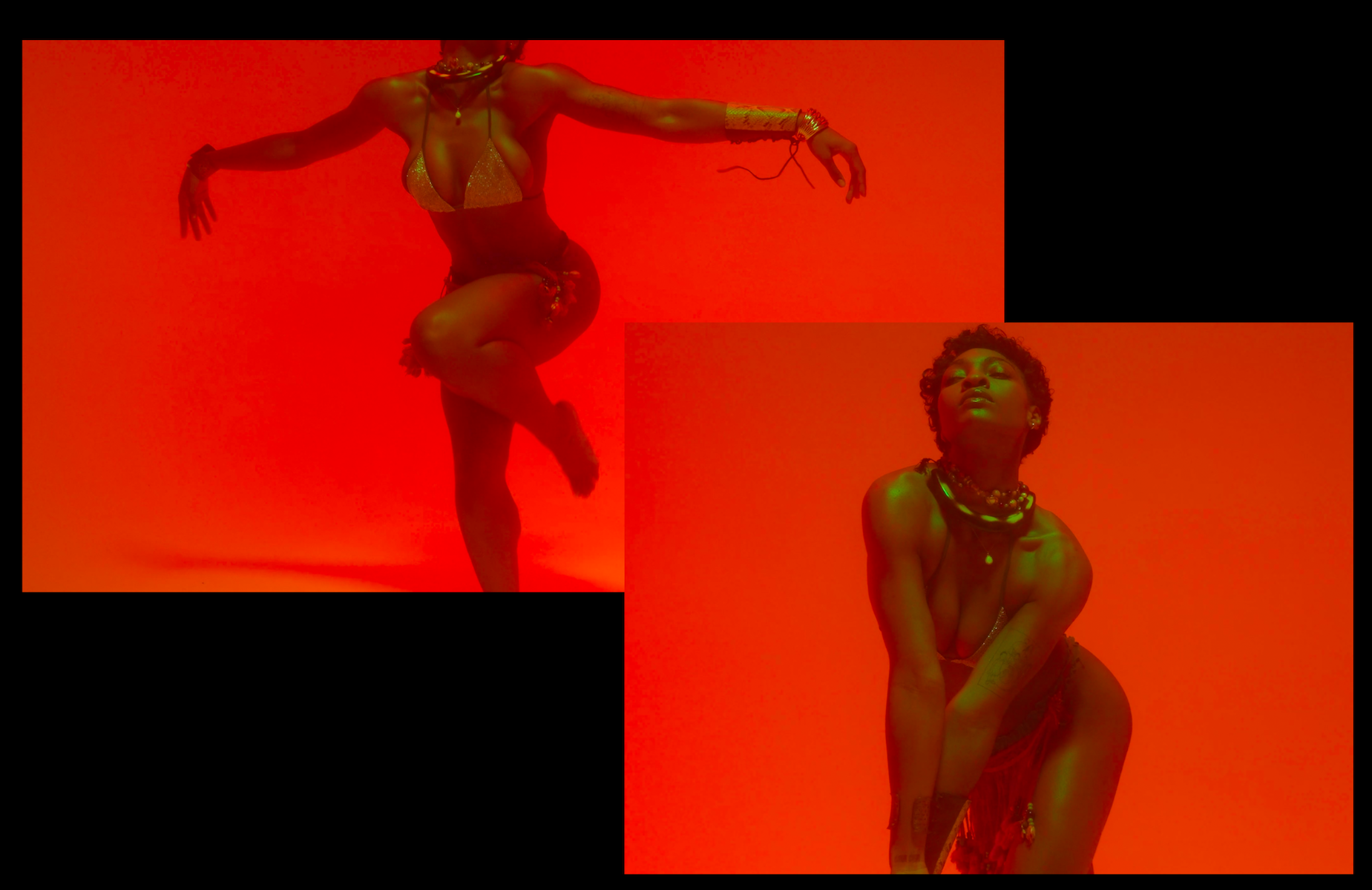

Her latest video project “DRUM GO,” shown in the stills accompanying this interview, is an entirely improvised homage to Black diasporic dance, set to an instrumental by Toro Y Moi. “DRUM GO” complicates mainstream portrayals of Black female sexuality as deviant and low-brow, “paying homage to black eroticism's cultural prominance dating back to ancient African cosmology” through the visual language of fast-cut viral social media clips and 20th century video vixens. “I’m stripping away the last form of branding from being so heavily institutionalized in my thinking and in my creativity, which is essentially the repression of sexuality” SOL says. “I've had my intelligence constantly undermined — there's a humility and a modesty that is imposed upon you as a woman. I’d become ashamed of my sex appeal as I pursued higher education and more prestigious, sophisticated spaces. This is a renunciation of that shame.”

SOL joined office over Zoom to discuss fun as evidence of freedom, abandoning the rules of her training, and why she calls herself a theorist. Read our conversation below.

In the last year or two, you took a step back from working in media to focus more on your art practice, both within your dance and your other mediums. What led you to making that decision? Now that your focus is there, how has the relationship evolved between your more tangible art practice and your other work, like speaking engagements and producing?

I am someone who is a student by nature. I really prefer to just get into the weeds and understand things on a technical and theoretical scale. So even though I had gone to performing art school my entire life, and then continued to train professionally and tour as a dancer by the time I was a senior in high school, I started to become interested in filmmaking when I transferred to Harvard from Middlebury. I abandoned the degree I was already pursuing. I started to study film because I wanted to know it in a more robust way, and I didn't want to have to self-teach in something that is super technical. I was always working within artistic mediums very closely because I was in school for them, but I was also working professionally to make money.

I hadn't honed my clarity of what I wanted to say to the world when I started working in media. There was sort of an intersection of my work with activism and my academic theoretical work, but I created this boundary between them in which I was working administratively within media rather than creatively. It was corporatized, so I just used it as a training ground. I got to a place where I'd established myself as a facilitator, established myself within media production, and my strategy work of finding ways to mobilize messaging was proving very effective, so I was getting work in that arena. Financially, the constraints aren't the same for me as they once were. And with that, I was like, ‘I’m ready to show what I actually care about.’

I'm ready to abandon all of the indoctrination of all of my training. There's a super major taboo that says you can only dance until your body gives out when you turn 30, and you can't do anything else if you want to dance. I was told all the time, “you can't go to college if you're going to be a dancer,” from the time I was six years old. It was like, “If you're really good, you're going to apprentice with a company, and then you're gonna get picked up and you're gonna tour and that's going to be your life.”

I just don’t agree with these concessions of having to bound myself in these ways. And so I tried to maintain my training and my facility, which is how it's referred to in dance, as well as possible throughout college. Once I graduated, I was ready to dance again, to dance professionally — and I didn’t give a fuck what anybody said, because my body is in the condition to do it. What I found even more miraculous is that my movement quality and style, which is particular to each dancer, had completely morphed in the absence of being in traditional training spaces. Because I was just out in the world, I don't know the influences that were enacting on my body, but they were changing the way that I moved. Despite having a very rigid classical background, I took to improvisational movement and blending genres and interweaving things and dancing to different scores than what you would traditionally see the movements I was doing paired with. This new nebulous practice just opened up for me. Once I felt more confident in it, I began to share it, and then I began to find work as a dancer.

Tell me about this upcoming lecture. What will you be speaking about? What have you spoken about in the past?

This upcoming week, I'm visiting a class that is focused on feminist joy. When I first attended Middlebury, I was studying gender, sexuality and feminist studies, along with history and international politics. I was preparing to create my own major there.This class was created as a response to the symposium last year that I was one of the lecturers for. I'm coming during their unit where they're studying eroticism; they're reading Audre Lorde’s Uses of the Erotic the week that I come, and then the keynote talk I'm doing is called “Deviant and Defiant Love: Paths to Self Fulfillment.” I’ll discuss the ways that rebels, freaks, and outcasts have been the catalyzers of major social and cultural transformations, and participants will reflect on nature as a diagram for cultivating self love and receive tools for overcoming insecurity in pursuit of their greatest potential.

Last year, one talk was called “Fun as Freedom: Alternative Proxies for Feminist Coalition Building,” and another was called “Blood Bound,” that was talking about my organizing work prior to going into media, which was in feminist menstruation activism and anti-poverty work.

For “Fun as Freedom,” though they wanted me initially to discuss my work in media, being the youngest co-founder of this media company with all these mavens, I actually decided to frame the talk around how I abandoned the convention of young professional ambition. The genesis of it was that I had gone through a period in my senior year at Harvard, where I was working full time — I was producing for TED, I took over the guest host role for Brittany Packnet Cunningham on her podcast that I was also a producer on because she was on maternity leave, I was on panels and doing a speaking circuit with one of my co-founders. I was working more than I'd ever worked while I was finishing my senior year. I was also going through a really, really, really hard breakup. I was going crazy. It felt like a really pivotal moment in my life, but I couldn’t really express it because there was an expectation of professionalism that I didn’t want to breach and topple my success thus far.

But something told me I needed to go in the exact opposite direction of my fear. And so I dyed my hair blonde, and I changed my Instagram name to “prettybadass.” I started to throw parties and started to literally introduce people to psychedelics in a really organized manner. I created a punk collective called “Sookie Sookie.” I was so afraid of destroying this one persona of myself that I realized it was critical that I do exactly that, otherwise I would be imprisoned. And so I did the speaking circuit with my bleached blonde hair. I was doing break dancing at this point. There was a lot going on. [Laughs]

But it made me recognize that fun is such an organic sensation. You're either having fun or you're not, and you know it when you feel it. I recognized that in a sense, fun is actually a really good indicator of if you're free, because you can't engender the feeling of fun while you're stressed or anxious or sad or afraid. Even if it's just the intermediary sensation in between these other anxieties, fun is not a comorbidity of stress and sadness. It is the absence of it.

I was doing prison abolitionist work, from the time I worked as a clerk in the public defender's office in Baltimore on their felony division, to my time organizing with Black and Pink, to my independent work. At one point we were doing noise rallies outside of Brooklyn [Metropolitan Detention Center], banging on pots and pans to let the people inside know that we were there for them. That was all it was, and it was fun. During the queer liberation parade during COVID, which wasn't supposed to happen but did anyway, I was photographed by the New York Times dancing — literally me twerking in the street. I've come to realize that this through-line of how I organized and how I went about building coalitions was not based on just collective suffering, but rather wanting to model what liberation looks like even within the confines of these oppressive matrixes.

For this upcoming talk, they came to me and said, ‘this is the unit, what do you think about it?’ And I think that my ministry has really just become rebellion and self sovereignty. Not looking to do these things en masse, but starting with an emancipatory view of yourself. What do you really want? Who are you really, what is your nature? That's why nature is the diagram for autonomy —things in nature operate just as they are, they're not being governed by anything other than how they operate, and everything seems to function.

For many years, you did your work relatively behind the scenes, and now you’re very consciously emerging into the spotlight. What caused that shift for you?

There is a very minimal digital footprint of so much of what I've done largely because I remained off of social media for much of my young adulthood. I needed a certain degree of privacy to change and become and experiment without having to be beholden to what I was saying or thinking or feeling.

It's interesting to be reaching a place in my career in which I am so present in the spaces I've aspired to be in, but there's this next leg of what I want to do. I want to reach people and I want to connect with people. I don't feel like I'm in a cocoon of self development anymore, in which I need to be hidden or feel that I don't want to be on the record. I've cultivated my perspective and my voice clearly enough that I'm OK with even the faults and the errors being documented. I want for my gifts and my talents to be recognized, as well as to be able to honor the people who've poured into me and helped establish my career up until this point for me to have the liberties to create the ways that I do with the people that I do. I'm not gonna retreat again until it is that I've attained the shit that I want.

I think you might be the youngest person I've ever heard call themselves a theorist. What does the self-label mean to you, and how do you find that framework helpful?

I wrestle with it because it's not sexy. [Laughs] I'm always sort of teetering a line of over-intellectualization and accessibility, and I don't mean this in terms of language because I am constantly telling people that the foremost critical thinkers in Black theoretical, sociological, and anthropological space were formerly enslaved people. I repeat that notion of accessibility not to mean the thoughts are too lofty, but rather that the label has been so co-opted and made insular to academia, when the most profound theorists I've met came from the hood, every single time. The most profound ideas come from my uncles, they come from my childhood friends, they come from people that are not traditionally educated. That’s why this is a label that I do take pride in, though I understand how it can be alienating. There are people who still understand that their experiences are the raw material of collective understanding. We're at a stage of modernity, where there's so much in recirculation, it feels like everything has been said, every perspective has been seen. I think a lot of people concede to the place of repetition and emulation — we see it in fashion and media, not just with trend cycles, but literally people replicating exact photo shoots. That is a form of becoming motorized, and I resist that.

I think I have perspectives to contribute to the canon. We've never lived at this time. Everything is unprecedented in that way. I'm seeking to make meaning or discover meaning, and to extricate myself from the shame that I may say something wrong — or I may say something new, which is also quite terrifying. In the beginning of Alice Walker's book In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens, she actually quotes Van Gogh, who said that he was struggling from a scarcity of models. I feel that for myself, as well. I want to canonize my thoughts and my experiences for people who are like me. I feel like there is something revelatory to our individual experiences, and I'm authoring mine.

Born in Canada in 1971 to Chinese immigrants, Mao was brought to Michigan as a baby, where he would live until his departure to New York in the 90s. Art has always been a fixture in Mao's life, motivating his decision to study and earn his BFA at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. The 90s art world was very different than today's, where diasporic voices and artists of color were discounted, either ignored or misunderstood. This culture of exclusivity prompted the then-New York-based artist to acquire skills in foundry work in San Francisco before returning to New York and beginning work at a design-build architecture firm. While simultaneously making art and begging more and more questions, Mao found himself in Mexico City for a residency in 2014 — a city that he now calls home. Mao's life journey has forced him to consider himself in this transnational context, informing much of his work today.

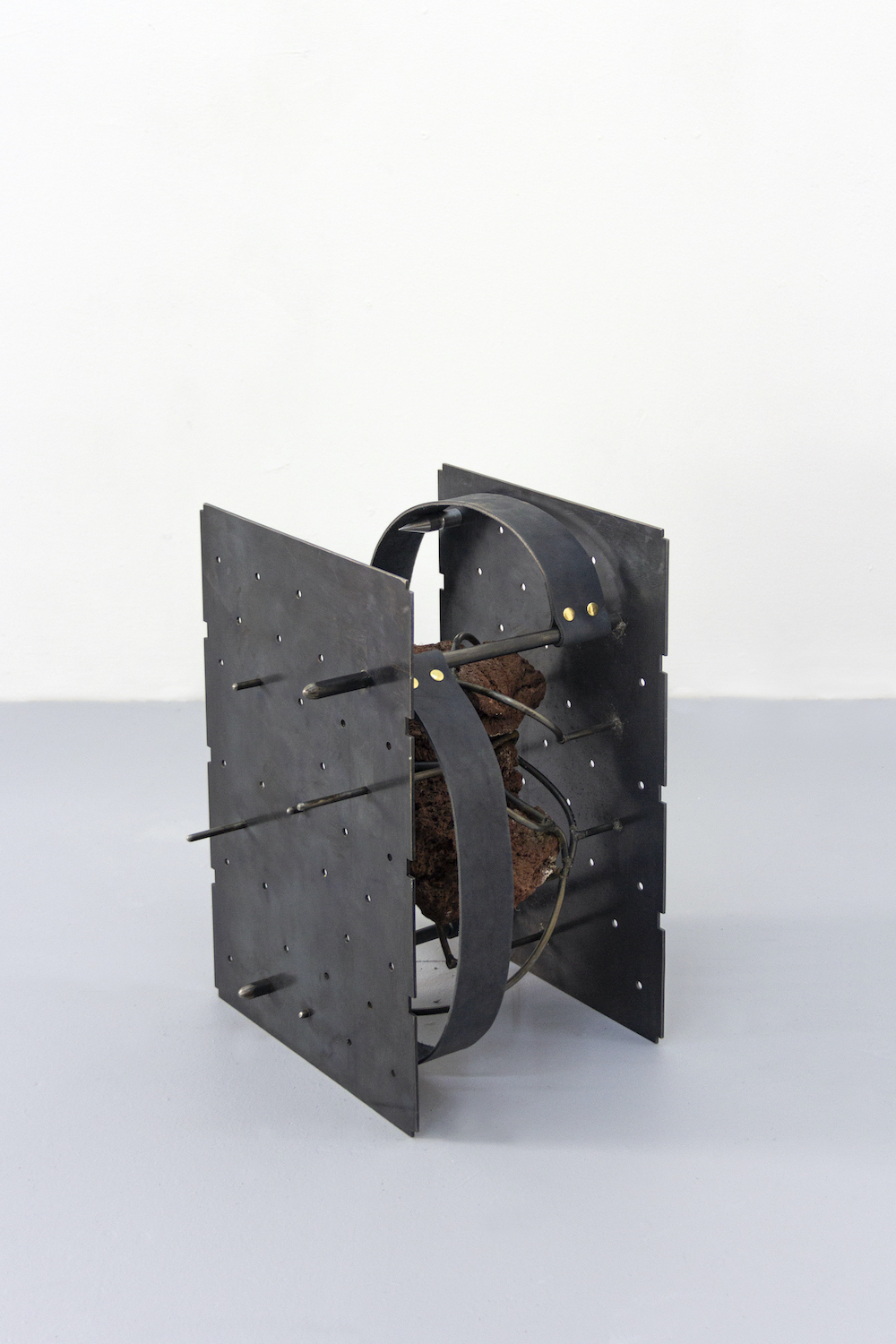

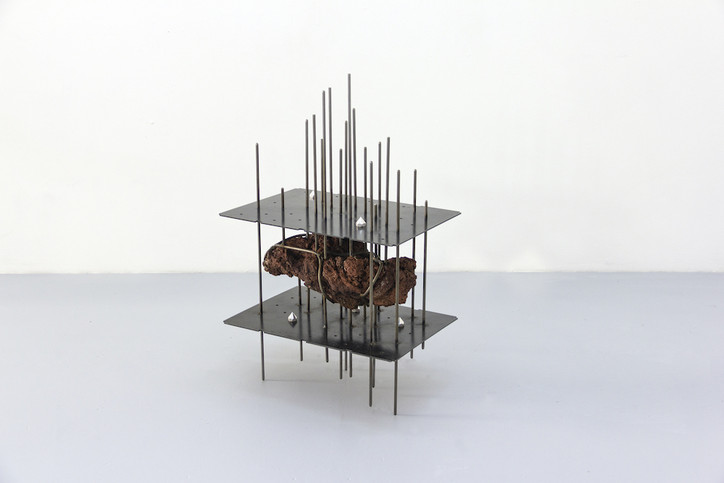

At the beginning of our video chat, Mao mentions how his forthcoming offering at Freize is years in the making. "For the Frieze presentation, I'm basing it on this research that I've been doing for some years now," the contemporary artist explains. "Freemartins" came to be through investigations into Mexicali and its "impenetrable history," a Mexican border town housing the largest Chinese population in the country. In the early twentieth century, coinciding with the Mexican Revolution and exclusionary laws implemented by the United States, the Colorado River Company exploited many Chinese immigrants through work in agriculture and irrigation. The unfamiliar climate and hot summers prompted Chinese workers to build out their basements into a tunnel system, an underground city called "La Chinesca." As the years passed and anti-immigrant sentiment began to spread in Mexico, La Chinesca became a refuge for the city's Chinese population. "Now the tunnel system is only reduced to just these few basements," Mao explains. "I have measurements of these basements. So I use the floor plans of them, and they're cut out of steel plate, and then using that as a basis of the sculptures."

Establishing an underlying — usually nonlinear — narrative is a common thread throughout Mao's practice. After pulling directly from these artifactual spaces, illuminating ideas of liminality, and addressing opaque histories and experiences of diasporic identities, the Mexico City-based artist's approach to this project has provided a basis for much larger ideas. "These floor plans are sort of loosely assembled, so they look like they are coming apart and coming together at the same time. I can use that as the basis for other things, in my practice," Mao states. "Thinking about this orality and the body and architectural space, the dissolution of bodies, and our relationship to myth. This idea that I've been playing with a lot lately of us being related to mythical creatures and sort of relating that to this idea of animism. These animals urge an intelligence of the body — beyond the spiritual mind. All that is sort of inside of these sculptures."

This richness of depth and embedded intentions is apparent not only in the work as a whole, but also in the details and the materials themselves. "[The material] is about this threshold or boundary, decomposition, and composition. I'm thinking about them as material that is moving through time in some way that is breaking apart," the acute artist mentions. "Steel is one of my main materials. Steel is made out of a few elements that have been industrialized into a thing, and then, it's possible that it can rust and disintegrate and go back to the earth." This notion of transience remains a pillar in Mao's practice and an essential facet of "Freemartins," engaging in ideas of fragmented histories, considerations of one's position in nature and the industrial complex, and relationship with time. Fig 39.7 Bardo, the steel armature confines the lava rock, pierces steel bars through the natural material, where a silent dialogue of ephemerality is being had.

fig 39.1 freemartin, 2024

fig 39.7 bardo, 2024

Although Mao's work is laced with conceivable qualities of anthropomorphism and narrative, the work traverses realms of abstraction where discoveries offer more questions than answers. "I really believe in abstraction. And I think that abstraction is hard to talk about. It's hard to write about, but there is this sort of liberation that's happening with abstraction where I can make a figurative sculpture that's not a figure. And it can, therefore, be open enough to talk about all these other things that are happening in the world that may not be as easy to define," Mao states after taking a drag from his cigarette.

Mao's departure in 2015 from the U.S. has allowed for uninhibited artistic freedom — igniting an inner part of himself. "I'm trying to embrace this structure of poetry and this sort of weirdness and abstractness," the esoteric artist states. Since calling CDMX home, Mao has produced incredible work featured in "An array of disruptions and codependencies," in London, "I Desire the strength of nine tigers" in New York, and "Yerba Mala" in Mexico City. Some of his recent work has delved into personal history and ancestral knowledge — a new exploration for the artist. These projects centered on "My mom, dad, and my grandfather, and all this stuff that I had sort of been ignoring, or maybe felt wasn't valid or worth going into," Mao explains. Now, with "Freemartins," an attempt to slowly make his way back into the United States art scene, Mao's subject matter of race, sex, transience, and issues of fragmentation appears as the right entry point to do so. "It feels like it's this sort of, not full circle, maybe a half circle moment," the 52-year-old artist notes.

As our call nears the end, I ask Mao where he sees his art in the future. He states, "I want to push the work. I want to embrace the abstraction in the work. It's an impulse for me to rely on aestheticism. And I think that the type of work when you walk into a gallery, and you say, 'What the fuck is that on the floor?' and 'Why is this in a gallery?' That's the kind of abstraction that blows your mind. Like, 'What is this object?' and 'What does it mean to us? Why is it even here? How did it come to exist?'" There's a slight pause, "I want this stuff to get weirder and weirder."