Miu Miu M/Marbles

The Miu Miu M/Marbles Stool is available for purchase exclusively at the Miu Miu Miami Design District boutique and miumiu.com.

Stay informed on our latest news!

The Miu Miu M/Marbles Stool is available for purchase exclusively at the Miu Miu Miami Design District boutique and miumiu.com.

office caught up with the woman herself, who talked us thorugh some of the themes of her craft, the flaws and failings of art's practicalities, drawing and storytelling. The exhibition runs from September 9 — Novemebr 4,2023 at PATRON.

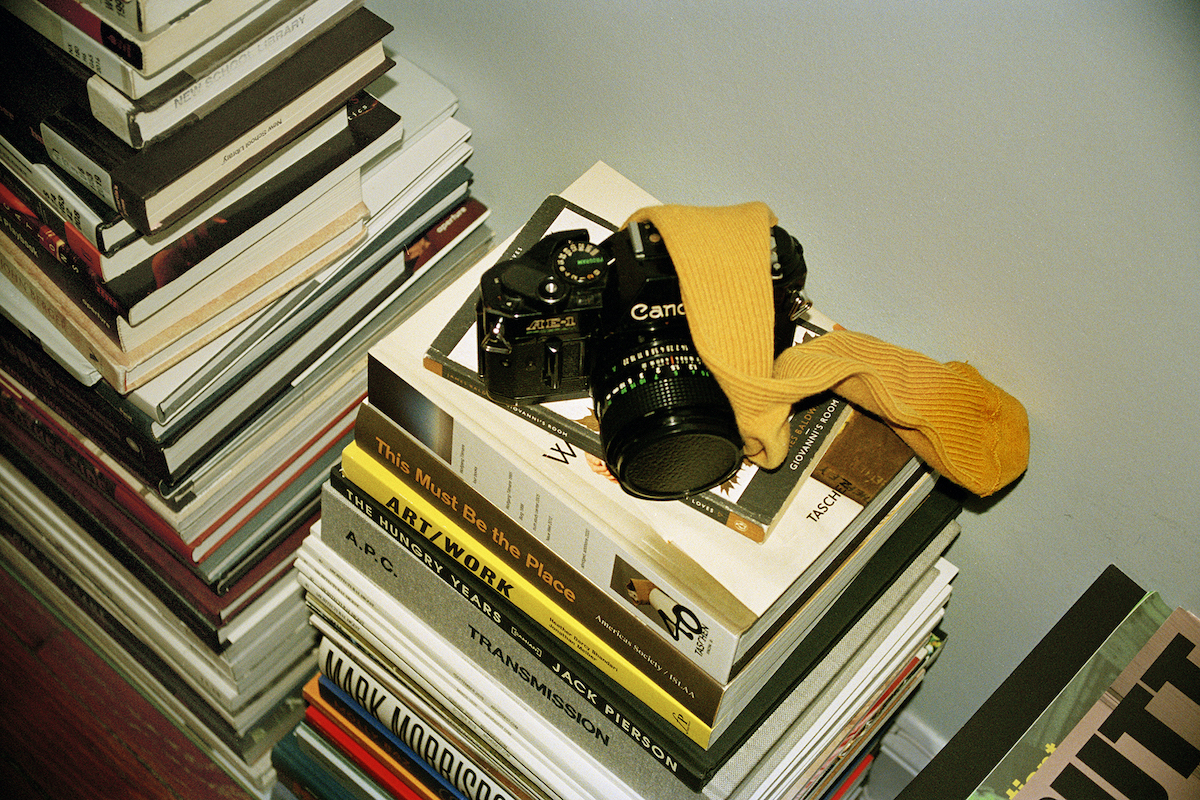

On Creative References

“I love what other people have created, like Lee Lozano, for the intense drive and emotion she puts into her drawings, the slow burning rage that I sense when I look at her work, and read about her experiences in the life she lived. I admire Leon Golub for his paintings that feel larger than life, depicting participants lurking over us, taking over the space and taking over each other as well. In the Rothko Chapel, there are paintings that have this softness about them, which is quite beautiful. And in Literature, Letters to a Young Poet is a piece of writing that I always refer to — constantly.

On Practicalities

“I embrace paradoxes, like the material I choose to paint on, which is burlap. It's a material that is opposite of practical and brings me to embrace so much failure over and over — because of its impractical nature. It's very hard to paint on, sucks up a lot of paint, it's very hairy as a surface, coarse, attracts dirt and dust, but it also brings me the textures I really strive for, and the paintings wouldn’t be what they are if it weren’t for this love/hate relationship with this material. It's a fabric that really needs to be shown love because it's not a forgiving material — one mark and it stays and is embedded. It's a material that loosens during the painting and drawing processes, as it takes on the shape of what it's holding. It's a material that is permeable and porous.”

On the Work Process

“I paint from both sides of the burlap, taking advantage of the permeable material the paint is able to go through. The surprise element is quite high, particularly when the surface is turned around and the painting is revealed. Since 2017, the act of drawing has become a very integral part: it has a very immediate satisfaction compared to the paintings which take a lot longer and are larger in scale.”

On the Unwavering Power of Storytelling

“Storytelling is fascinating and brings so much joy to me. It has the power to make us travel, travel to a time where we weren’t either present or alive — it can bring hope, sadness and also empower us. It is what teaches us lessons from the past, and it also can take us somewhere we haven’t been to — but most importantly, it can really inspire and influence us. It can have the power of captivating our full selves — and leave an impact.”

On the Message of History As Weapon to Inspire Society

“I am reminded of how history constantly brings us to remember the rebellion and resistance that have taken place, but sometimes we cannot imagine this. Looking at such elements can bring us strength and, in turn, become a weapon to inspire society. Just like tools, ideas too can be and often are turned into weapons depending on how we form and apply them — some of the best ideas always come from a deep examination of the past. Our learnings from the past is what assists us in the present and potentially the future—the past is a tool to move forward and gain knowledge for the current.”

Growing up in the heart of the Midwest, Levi's world was framed by vast expanses of open land. Living in a small town has a funny way of fixing your gaze beyond the horizon. For Levi that meant Florence. After having a dream of living in the European city as a shoe designer at 14, he told his family that he would one day move there and then eventually did.

It was in Florence that he realized his true calling was not shoe design, but fine art. He became fascinated with how people reacted to classical styles and the works of 16th-century masters left a lasting imprint on Levi, both technically and spiritually.

This influence is evident in his work, where he skillfully merges elements of organic life, simple geometric shapes, and themes inspired by the distant past. Visceral, imaginative and dialectical, his art transcends conventional boundaries of time and tradition, exploring the interplay between the past and the present, dreams and reality, and the potential of art to engage with the ever-evolving social, economic, and political landscapes.

Ahead of his plans to start at the Royal College in London this fall, we sat down with Levi to discuss his artistic approach and his contribution to the group exhibition at Southampton Art Center, SCULPTED REVERIES, which opened last Thursday.

When we first met, I thought you were raised in Florence then moved to New York. I didn't realize you were from Iowa. How long were you in Florence?

I moved there in 2017 and I was there until 2021, so about 4 years. I did two years of school in the States and then I did two years of school at the Florence University of the Arts and I just ended up staying way over my visa. My life got flipped on its head and I never wanted to leave. I spent every summer there.

Did you go there already thinking that you wanted to be a sculptor?

Not at all. So, the whole reason I went to Florence was because of this dream I had when I was 14 that stuck with me since. When I was 14, I had no reference of what Florence or Italy was, but I woke up in the morning and I told my family that I was going to move to Florence and become a shoe designer. I’m from a town of 6,000 people in Northwest Iowa, this kind of thing didn’t just happen to anyone.

I always felt somewhat out of place where I grew up and held onto bringing that dream into reality one day. Once I moved out there, everything kind of fell into place in a really weird way. After the first couple days I was there I met an Australian couple who owned a bespoke footwear brand who took me under their wing which then led to me becoming an apprentice for Massimo Guidi. Most weekends I would go to factories all around Florence, learning the business of footwear, how to design shoes, build a brand, and develop a process. Shortly after, I met a bunch of classical painters and sculptors and realized that the story I was trying to express creatively was not in footwear anymore, but in fine art.

I stayed in Florence for four years because I had the boutique footwear job, which just unlocked everything for me. I spent my summers in these little marble cities called Pietrasanta and Carrara, where I was doing finishings for different marble sculptors and learning how to paint. One of my best friends out there, Thelonious Stokes is an amazing classical painter. He taught me until I started to develop my own language and understood where I was taking my own practice.

Florence has such a rich tradition of classical art and sculpture especially. Did that influence how you approach materiality today?

Florence has some of the best craftsmen, people who honor the traditional approaches to making art so my initial introduction was from a very classical standpoint with traditional methods. Obviously, Italy has some of the best marble in the world. I was surrounded by lots of raw materials and material has a direct line between culture and history. Being from Iowa, the materials available are considered “low”— brick, cement, limestone, blue collar construction materials. In Florence, it’s terracotta, clay, marble demonstrating this distinction between the building blocks of the world and alternative social classes.

The material itself has a history to it. Someone learning sculpture in Iowa is going to be limited in the materials they have available in comparison to someone in Florence. That kind of speaks to accessibility.

Exactly.

Considering the cultural ethos of your work, are there specific conversations you're hoping to start?

Conversations I’m already having with my contemporaries, or within my practice are fueled by the unfortunate state of the external world. My understanding is that one can only create true cultural and social change by deepening their own internal world. Through this reflection and connection, I believe we have great possibilities to bring a cultural revolution that empowers and restores truth to its people.

How does your work influence the social and political?

I’m working on these landscape paintings right now and, and I'm thinking back to what landscape painting means and has always kind of meant from a classical standpoint — and then taking that into a literal contemporary sense. It’s obvious on the surface, but what lies beneath the format of transcribing a landscape is what I’m interested in. I’m thinking a lot about war and ownership, land conservation, migration and race relations, religious themes, materiality, my own evolution in the work, but even more so how sculpture functions in the world, and what that really means, as it can serve as a vehicle to create change within the contemporary world. I would love to be able to go to different places around the globe to create large-scale land art and large-scale sculpture, working with different communities to build cultural monuments.

Is it more about preservation?

To me, preserving culture is extremely important. I believe we have lost a great deal of tradition, information, and connection to the God source through the powers that be. I’m optimistic though, we are in a time where people are rediscovering these things and reclaiming the truth in which they came.

Your “womb” sculpture reminds me of a sort of basin. I could see it being used as a water catcher in a community that lacks multiple fresh water sources.

Absolutely. I mean something that I was just talking about the other day is how expensive water is and how there's such a shortage of water, but at the same time we have free New York tap water. However, a bottle of water is like $5. How is water not all free and accessible to everyone? I would love to work with urban developers to create basins for free water and make clean water more accessible to all people.

Polaroid photo, shot by: Max Tardio

I was thinking about this the other day. In our world, there aren’t many free resources. Everything useful has a price tag on it. Tell me about your show at Southampton a bit.

Sure, nothing is free in this world, but I do believe we have all the resources around us for the taking. I think what costs us is denying that fact. I had eight works that went to the group show at Southampton Art Center. There are six other artists, curated by Jess Hodin and Gaïa Jacquet-Matisse. The show opened on August 19 for their annual gala, and then on the 31st to the public.

How was that?

It was great, I put a lot of strong work in the show.

Tell me about your London plans. Are you excited to be in a different city?

Absolutely, I have a really good crew of people already in London that I met when living in Florence. I’m excited as I haven’t had any proper schooling in the arts and the Royal College has been the number one art school in the world for the last ten years. I plan to learn as much as I can from the professors there.

Has the sculptural tradition carried into London from Florence?

I think that every true tradition of classical fine art painting and sculpting emanates from Florence through the west, so London does have roots in Florence, but the city also has a rich history of artists and art making. Some of my favorite artists have come out of the college, like Tracey Emin and Anish Kapoor. London also has some of the best and most exciting fashion designers, artists and musicians. There’s something really special going on there so I’m excited to just tap into that.

Does your background in fashion design inform how you approach materiality as a sculptor?

When I first moved to Florence, I was learning pattern making, how to fit and drape garments on the body and learning how to make abstract work from a classical standpoint. I think fashion and fine art kind of rival each other for the highest expression of what art is. I definitely hold fashion designers in high regard.

A lot of what I’m doing with some of these sculptural paintings is draping — referencing the human form.

I overheard this conversation about universal languages and this idea of facial expressions being a kind of ancient language that nobody really pays attention to. It almost feels like sculpture and these forms that you're referencing, these classical ways of using material is also this language that just very few people are keeping alive totally.

I think a lot of human emotion and what we are really trying to express to another human gets lost in our silly use of words. That’s why I think abstraction and art is so powerful and emotional. It’s this kind of silent language.

How long are you in London?

It's an intensive one year program.

Do you have the preconception that you’ll return to New York after?

That's a good question. I mean, I literally just got married last week. and my wife is half Moroccan. After this past Paris Fashion Week, we spent about 10 days in Morocco and we're starting to talk about building a house and moving out there. In an ideal world, I would love to work with a major gallery and be able to have my studio and home life based in Marrakesh. It’s such a good pace of life. I feel really inspired out there.

I went to Morocco in 2017 and have been thinking about Morocco ever since and now I fully just got married to a Moroccan woman. But who knows? Maybe I’ll stay in London, maybe I’ll come back to New York.

On view at Southampton Art Center through Labor Day.

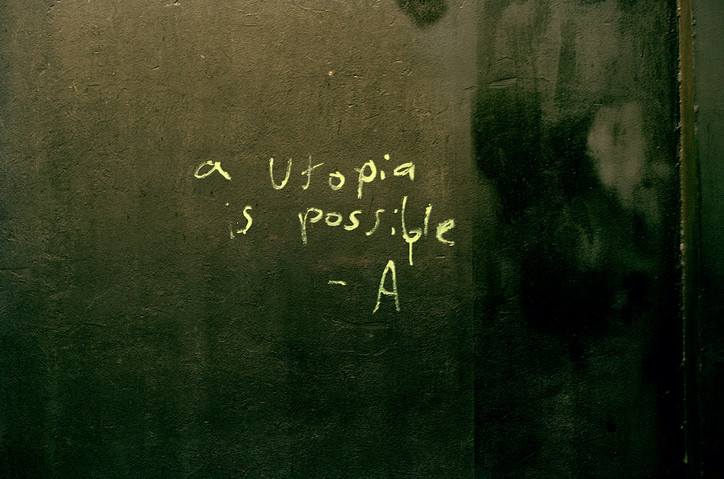

Otherwise overlooked, he approaches evidence of queer existence with care and reverence. Snapshots of unmade beds and overlapping handprints on bathroom stalls represent the beauty in the ephemera. Despite the suppression of queer life and queer living, Capacyachi’s documentation serves as undeniable evidence – not only of existence but of the love that was present. Photos of “IN PURSUIT OF dick” graffiti and a single plastic-wrapped cucumber are cheeky and conspicuous; the act of queer sex itself is not only an affirmation of queerness, but an expression of queer joy, love, and lust. And what is more utopian than the ability to recount love in even the smallest of instances?