Miu Miu M/Marbles

The Miu Miu M/Marbles Stool is available for purchase exclusively at the Miu Miu Miami Design District boutique and miumiu.com.

Stay informed on our latest news!

The Miu Miu M/Marbles Stool is available for purchase exclusively at the Miu Miu Miami Design District boutique and miumiu.com.

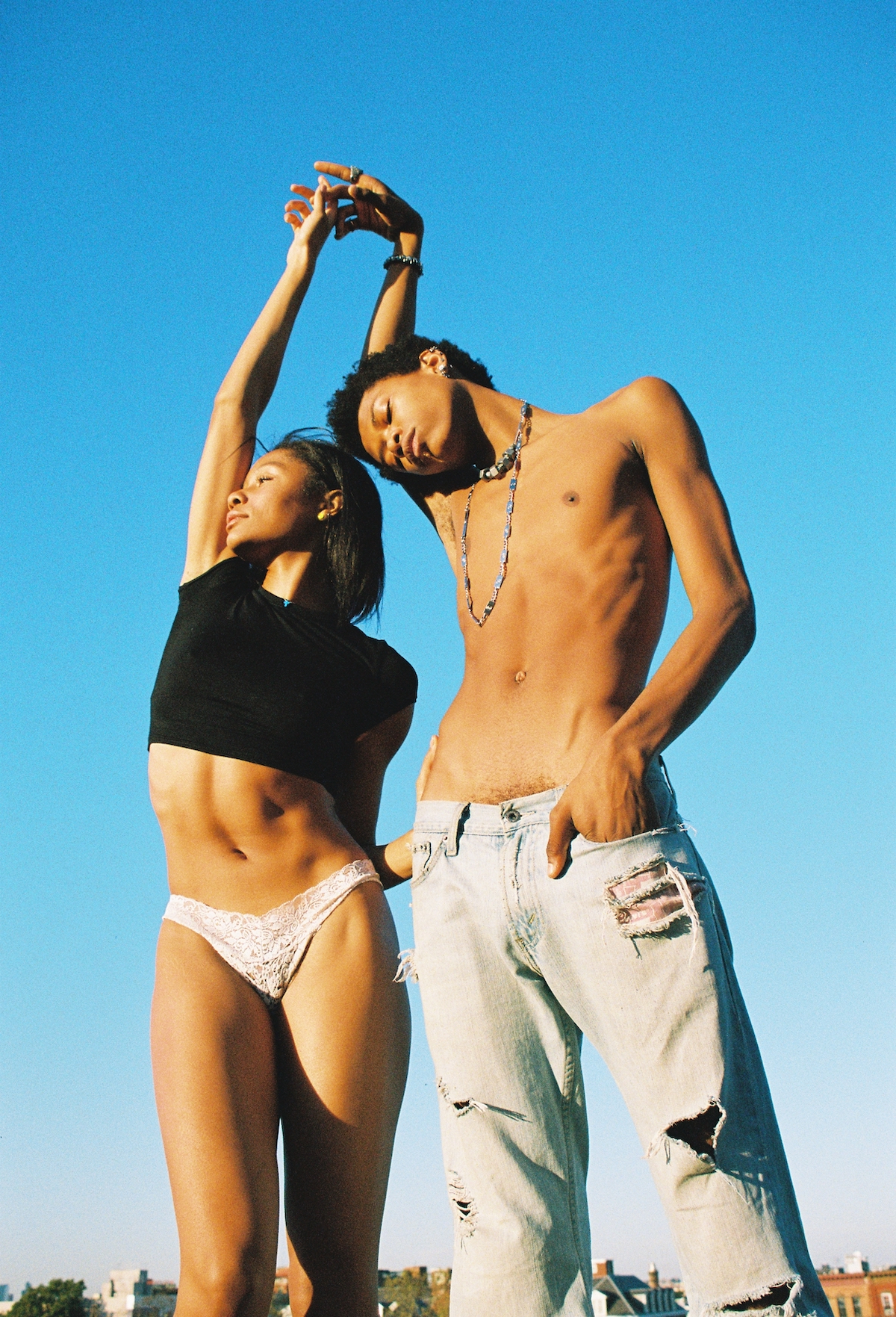

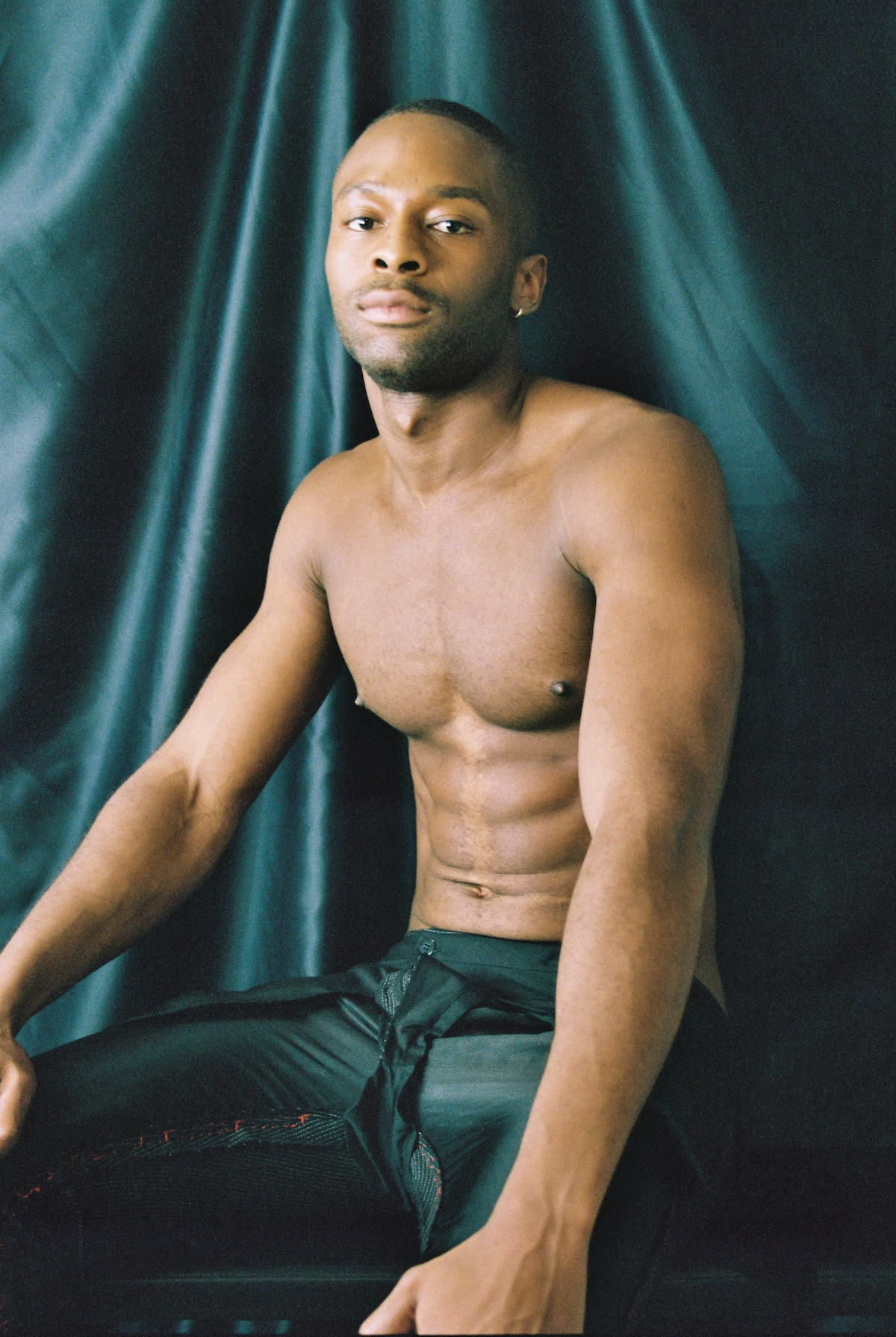

In light of his latest release, office sat down with Rennt to unravel the magic behind his photography, book-making process, and presenting his work uncensored.

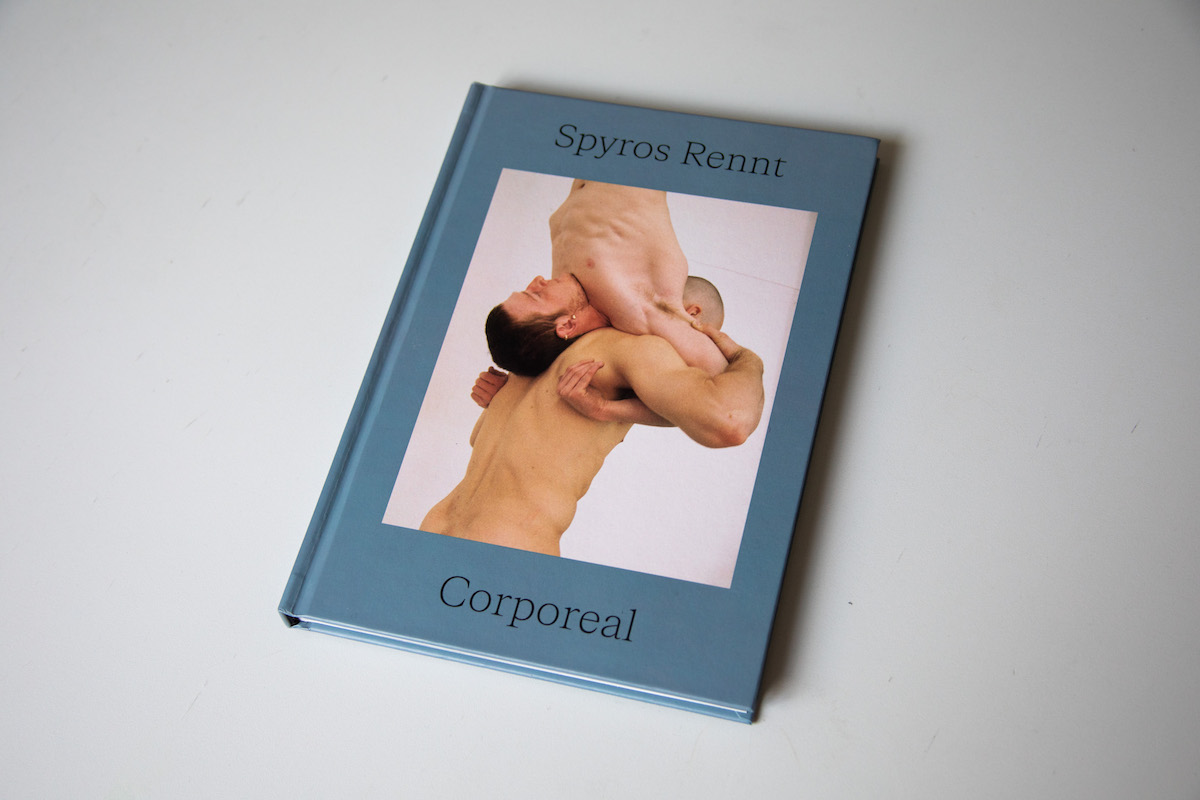

Corporeal is your third self-published book. What about this book makes it your “most comprehensive work to date”?

To be blunt, I think that I'm a better photographer and book editor than I was when I made my first book in 2018 or my second one in 2020. When I made Another Excess five years ago, I was hardly shooting for a couple years; the book does have a great energy and it really pushed my career forward, but there is also a certain naivete to it. I tried keeping the sexy energy, but there's also an undeniable maturity to Corporeal, which came with me being more experienced. It's also been three years since Lust Surrender, my second book from 2020, so I had a bigger archive of images to select from.

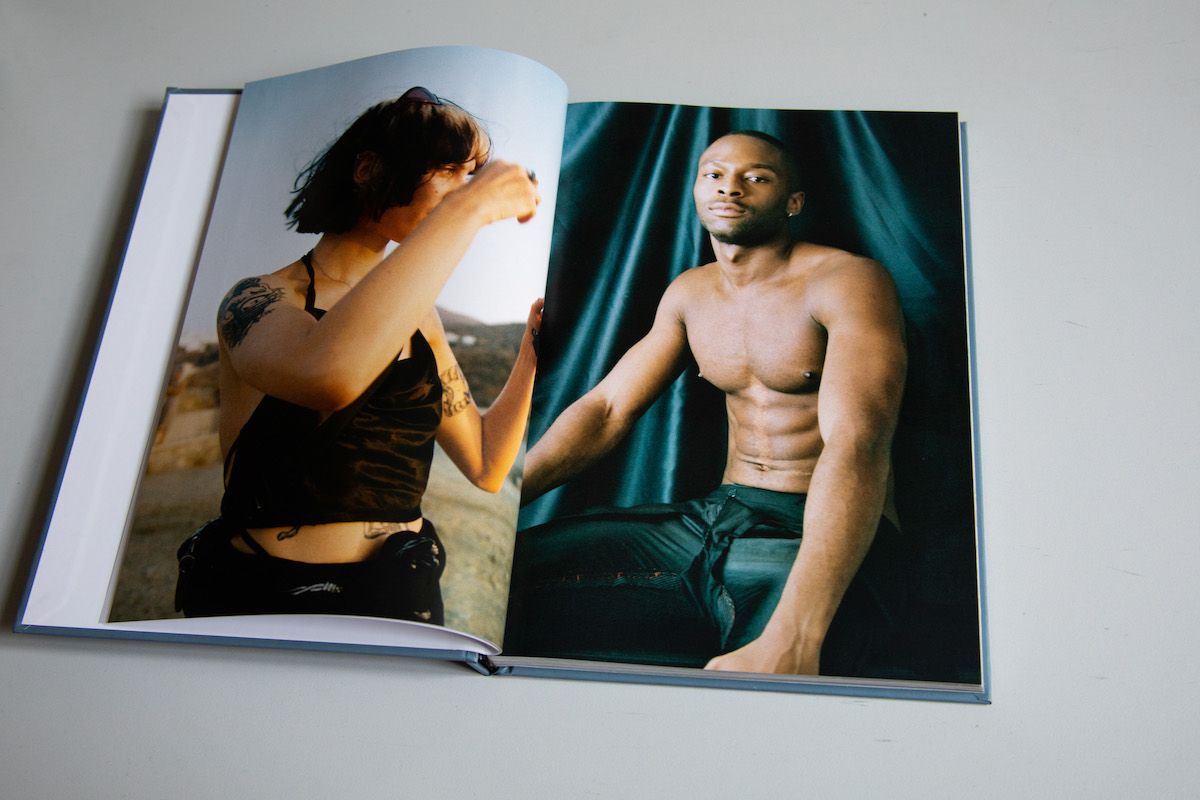

It’s also your first book with a hardcover. What prompted this decision? And does the physical presentation of the book contribute to the storytelling in any way?

This is clearly an aesthetic choice about how to present the book, but from my experience it tends to be what a buyer is looking for when they are purchasing a photography book for their collection. I knew I wanted a hard cover when I started working on the book; I think it's also a nice expression of my evolution as a bookmaker.

If your photos create a new realm, what emotions inhabit it?

Warmth, closeness, desire, intimacy and freedom of expression.

One of the unique aspects of Corporeal is that it presents the experiences and observations of different communities from an insider's perspective. Do you purposely record people in communities you consider yourself a part of?

It's what I've been doing since I became serious about my photography practice back in 2017: I started documenting the scenes that I was a part of because this is what felt the most natural to me, it's what I had access to — but also I genuinely think that the situations and the faces that I am documenting deserve to be archived and preserved for future generations.

How many different cities does the book take us through?

The two main staples are Berlin and Athens: the place that I call home since 2011 and my hometown, where I still spend a good part of my time. It's not just these two cities. As someone who documents his own life to a great extent, my camera follows me wherever I go and I do travel a lot. Off the top of my head, the book also contains images shot in Paris, Milan, Barcelona and of course a number of greek islands. But Berlin comes first, followed by Athens.

Are there any moments recorded in the book that stand out to you?

I wouldn't call them moments exactly, it's more of an era: there's a good number of images taken around the summer of 2020 when clubs were closed due to covid but we were all partying in houses. There was a certain rawness to the images created in that time and I'm quite pleased with how they have been integrated throughout the book.

Does social media influence your photography in any way?

It does in the sense that when I'm shooting a person, I'll shoot them the way I like but I'll also create some content that's more social media friendly, which is basically a big reason why I do publications: to share the uncensored version of my work; to be in control of how the story will be narrated.

What’s next for you? Are you working on your next book already?

Corporeal has just been introduced to the world — it's always a journey when I do a new book and we're still at the start, so I'm mostly working on promoting the new material, planning the launches, possibly some exhibitions. I do have in mind a new publication for 2024, a more specific project, but this lives very much deep in my head still — my main focus is Corporeal at this point.

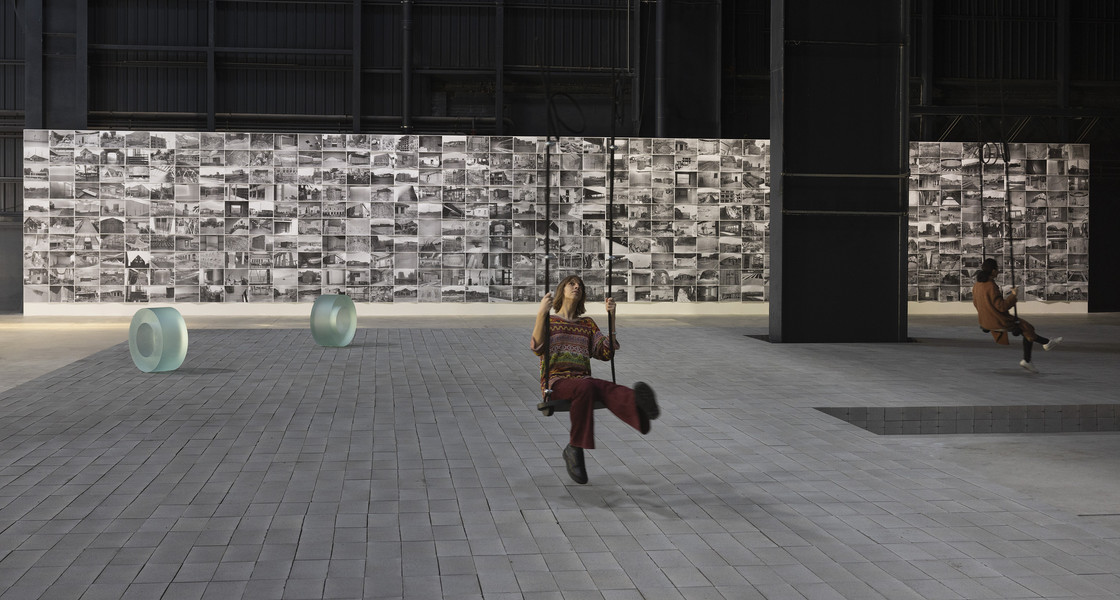

Where the open air brought gushing groups, Pirelli Hangar Bicocca (formally a tyre factory) was discreet — but far from empty. However, from April 6th until July 30, there is a beautifully curated (by Roberta Tenconi) show of Belgian artist Ann Veronica Janssens. This show is neither blaring nor tacit. It is something different altogether.

Spanning over four decades of practice, ‘Grand Bal’ is an exhibition of Janssens’ past and recent works. In the high walls and darkness of the now art warehouse, the collection of her installments, sculptures and immersive artworks have a multisensory rhythm that controls the space with a resounding beat. The old factory sheds thin cracks of light from the outside, spraying the concrete-bricked platform (Area (1978-2023)) specifically made for the exhibition. Swings (2000-2023) swung from the ceiling sparking nostalgia, and a group of TV monitors crowded a corner, spurting sound and images from the concrete floor.

The show was dynamic and spread across many planes, hitting elements, senses, and sentiments. Janssens transforms ‘our environment’ into hers. Observing this space, one can imagine her sauteeing pretentious, white-gloved verbiage — characterised by formalist approaches and installation norms — and reducing her work into bubbling synaesthetic stimuli. The installations are prepped for the pass (or ‘consumption’ if you don’t want me to beat the metaphor further). Unlike the raw and raging Design Week, Janssens gave Milan a place where material and light sat in a flux of paused time. Her work held everything in an inspiratory pause (the moment between breathing in and out). Suspended like the floor-to-ceiling foil PVC sheet, Golden Section (2009) shifts before the entrance of the completely fogged-out ‘mist’ room (these have been synonymous with her work since her exhibition of the immersive fog environment at the 1999 Venice Biennale.) From afar, all her works are just as ambiguous, but up close, their contents drown the experiential palate with vivid piquancy. Or mist.

Back in town, groups of buyers, editors and designers bumped into each other as they passed through furniture and fairs. Their plastic cups drop lime wedges onto beer-sodden shoes. There was so much action, so much noise, and then static. At Pirelli Hangar Bicoccae, the static was welcomed. Apart from the fog and swing, the screen and supine mirrors, Janssens’ rectangular anti-room is stuck in my mind. It is a dissolution of space (ironically named ‘infinite space.’) It is silent, isolated and isolating. It is an apotheosis and a black hole, everything and nothing.

And in front of it was a chair. And the tired security guard stood watching that chair, wholly consumed. I could tell he wanted to sit.

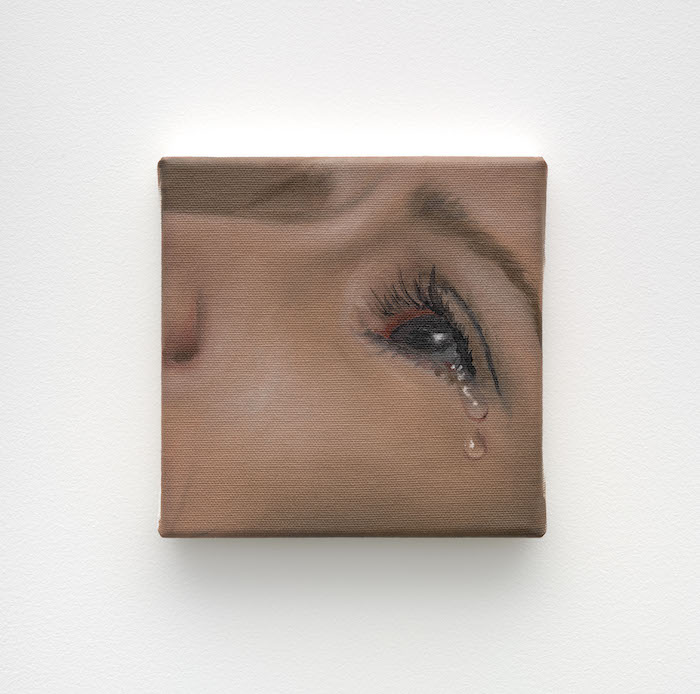

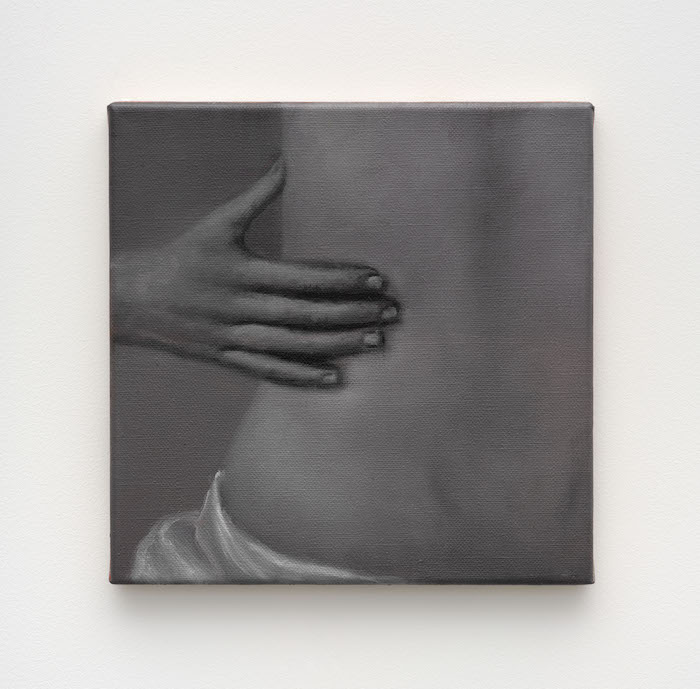

office sat down with the artist to discuss this new series of paintings and the multiplicities that simple snapshots can encapsulate, below.

What is your artistic origin story and what initially interested you in the medium you currently work in?

It was a journey with a lot of twists and turns for me because I basically went through every medium before I discovered painting. I was quite consistently working with sculpture and installation for a number of years before I started painting. I think there were some mental barriers there. I feel like the main benefits of art school for me were not what I was conventionally taught, but what I had to dismantle because it was a weird experience. It was beneficial in some ways, but I feel like looking back on that, I didn't feel completely rewarded by the stuff I was making. I felt this need to reconnect and ground myself in my own voice. I think it was 2020 when I was doing an art residency in Seoul with the Seoul Museum of Art, and I pitched an oil painting residency to them and that was the start. I didn't really know what I was doing so I made quite a few mistakes in terms of the technicalities of oil painting. Though it just felt so natural. But in terms of how my practice and the content of my work brought me here, I was dealing with a lot of these fragmented narratives and scenes. I like the idea of taking viewers on a journey that might take them into weird recesses of their own subconscious. So much of my work is about the whole concept of evocation and I think images themselves are such a perfect way to talk about and to trigger emotions in someone.

It's like we're constantly locked into this stream of thought and imagery in our natural mental states. We often limit ourselves by the way that we box things in and simplify things down. So I think, sometimes, one of the major functions of my work is to take that tiny fraction and expand it. I was just interested in the fact that such a simple image can do that and evoke visceral and emotional responses.

Why do you aim to explore what you call “the elusive language of the body and mind” in your work? What sparked this pursuit of unseen knowledge?

I think it's a life philosophy that I have. Growth is dependent on friction, so as soon as you step slightly out of your comfort zone or into this new realm, you're in more of an aware state. And I think that's something that I was kind of fascinated by — the strength of challenging emotionally intense experiences or moments in life that kind of trip us up. It's eternally challenging to step into the unknown. And yet, I'm so invigorated by it and I try to make a practice out of it in my life. So it was just a no-brainer. It was less something I decided to practice and just a part of my life that I hoped other people had an interest in too.

You mention that dualities are at the heart of your work. What dualities make up who you are and how do those juxtapositions appear in your craft — maybe in your color choices or even down to certain gestural brushstrokes?

That's such an interesting question. I feel like there are some personality traits that I bring into the physicality of my work in some ways. But maybe that's just all art making to some degree — it all walks the line between softness and quietness and observation and stillness. A lot of my practices also go leaning into strategic analysis and the associations between images and the bigger picture, so there's this constant zoom-in and zoom-out that I think I'm like always doing personally. And that is definitely reflected in my practice because it's like you've got these tiny scenes or little snippets, but then for me, the most intoxicating part is the combination of images. The paintings themselves often come together pretty quickly, but it's choosing the image and the colors and all that that I get really lost in.

I've also been trying this new thing lately. I used to paint like I was drawing, but oil painting is not like that. It's the push and pull of paint and color and mediums. Lately, I'll make a very perfectionistic painting and then treat it afterward or brush over it in a certain way that adds so much more ephemerality to it. Because for me, I don't love hyperreal work. I prefer for it to still have that dream-like sense to it. At the same time, I'm so drawn to rendering that I can't seem to abandon it. So that's a duality too. I'm constantly trying to take a step back from whatever I happen to be telling myself about something and then add in more context or question it again. Because I think, ultimately, every time I feel like I have certainty or absolute truth about something, then I'm probably on the wrong path. Things should be more gray and multiple things can be true at the same time. And that's the cool thing about life.

Growth and ephemerality are two central themes of your work, as you explore the ever-changing landscape around us. How have you grown, personally, since the conceptual creation process of Love Story?

My last two shows have definitely had more of an autobiographical streak to them. So in some ways, I was navigating family experiences and experiences with loved ones through these works. So there really was a huge therapeutic element to it. I think I was experiencing one of those universal experiences where intimacy can slip very easily into pain. It was something that I hadn't really tackled head-on, necessarily. Love Story was about me going through a lot of those big emotions at that moment — feelings of yearning and love and intimacy. And at the same time, a lot of resistance and self-control and all of these challenging emotions that we feel as we grow up and come into periods in our lives where commitments are deeper.

So I thought the only way out was to make this work. It started with the black-and-white images. The first one I painted, called "Press," recalled these little gestural moments that I was thinking back to and how consuming this experience had been, and how in my mind it became distilled down to just a few little fragments. I felt like these were the perfect introduction to this show because they're all things that happen in a home and in a domestic setting — things that can deeply rattle you and stick with you. But even when I'm starting with something really personal, I wouldn't go deep into it if I didn't feel like I could share that experience with others who may have navigated the same things.

Many love stories, as you address in your works, create unattainable ideals or fantastical narratives as a means of escape. If you could write your own contemporary love story, how would it differ from those we consumed growing up?

I'm a victim of the ideals as much as anyone else. I think we all are and it's something that you constantly have to remind yourself not to do. But at the same time, I feel like if we go too far in the other direction, we can run the risk of disengaging as well. Maybe my story would highlight intersecting moments between not just two people, but many people. Like how a movie will tell a lot of stories at once and then they kind of intersect. I think the more we understand the people around us, the better we can navigate the world.

I think we definitely need more non-linear love stories because it’s realistic.

There's obviously tension and monotony in this work — there's an immense sense of loss. You could read that as, 'Oh my gosh, what a depressing narrative.' But I really think, more than anything, that there's beauty in the simple, everyday moments. It makes me think of the movie Everything, Everywhere, All at Once — the mother and father realize that there is joy in just doing laundry and taxes with each other. Sometimes it is the simplest moments that make me feel the most depth.

We talked about traditional love stories, which often conjure images of whimsy and those images might be super colorful. But the color palette employed in your work is dark and a little bit demure. I know we just discussed monotony, but why did you choose to construct your works in this way and where did this choice of color come from?

A lot of it is supposed to mimic when you're trying to remember a dream and you don't remember it — it just comes out as blobs of gray. That's kind of how it seems in my mind anyway. But, actually, the darkness is just an evocation of that which is unseen, which I find alluring. So I think that was one of the reasons that I make paintings in these darker hues or those muddied warm tones. I feel like I'm constantly going back to browns, grays, and greens, but I'm also really obsessed with red and I feel like I can't seem to stop painting with it. I love color as its own conversation and I think it can be so symbolic. Like with red, there's something very corporal; it's like blood and flesh. I also wanted to show the dualities of love in my work. There is that conventional lighthearted love, as you said, but it can also be bloody and gory — especially given traditional symbols of live human organs and hearts.

You state that you think of all of your paintings as the sum of a larger whole. One that may not be fully understood yet, but if you had to put words to that larger meaning or goal — what would it be?

There's a line on my press release for this exhibition that I love. "We look for an answer to ourselves, something through which we ascend or escape our physical bounds. Yet despite this hopeful belief, we know that purity could shatter, giving way to less transcendent feelings. It seems to me that there's little difference between reality and fantasy, memory and imagination.” If I had to pin it down to one thing, that's what it would be. Because I think it encapsulates everything. It's like we can't help but simplify everything down to these little moments. We might have this whole robust experience, but for whatever reason, because it's impossible for us to remember everything, we condense things down. And I think that whole concept is particularly strong when it comes to love relationships, whether that's romantic or otherwise because we are playing in this field where the stakes are high and we're vulnerable. We want to be seen and heard and we want to experience intimacy and love and connection. And I think when those things are all on the table, you start to hunger for a very specific moment or a very specific gesture — or you remember only that which served your sense of joy. Or it might be the opposite. It might be that you only remember the hardest elements if it was a really challenging relationship. That for me is what this show was about. And I'm hoping that viewers realize this phenomenon and that we really do need to sort of dismantle the stories that we tell and the things we hold onto.