The Modern Muse

Stay informed on our latest news!

Where did the name Jai Street come from?

The name Jai Street reflects the creativity that inspires our work, and that I initially found on the streets of the LES. Jai comes from my last name and is a modern pronunciation of the Sanskrit word for admiration or respect.

How do you select your features?

We look for is artists with a story to tell, appreciating artists equally regardless of where they're at in their career.

Growing up, were there any magazines you were an avid reader of?

I grew up with and am an avid reader of 032c. This admiration grew when I was starting Jai Street. By trial and error, as I learned the ins and outs of creating a magazine, I had 032c as a physical almanac of all things culture. It was a sort of guiding star and inspiration, something to work towards. The fact that one issue could span from the streets of Berlin to Seoul to New York and feature such a wide range of people and stories was something I admired and want to do myself.

You say trial and error, was there anything in particular that you learned?

It's a bit of a hustling game when you're doing it independently. I spent last summer going around the city with copies in my bag, trying to get them everywhere. Distribution and getting it out there is really hard. You don't just make a magazine and get it into stores. We've been really grateful to sign with a distributor who's helping us create a map for this. There was a lot of pressure. What if people don't find it or come across it? But it also motivates you to create the best thing you can.

Have you learned anything about yourself?

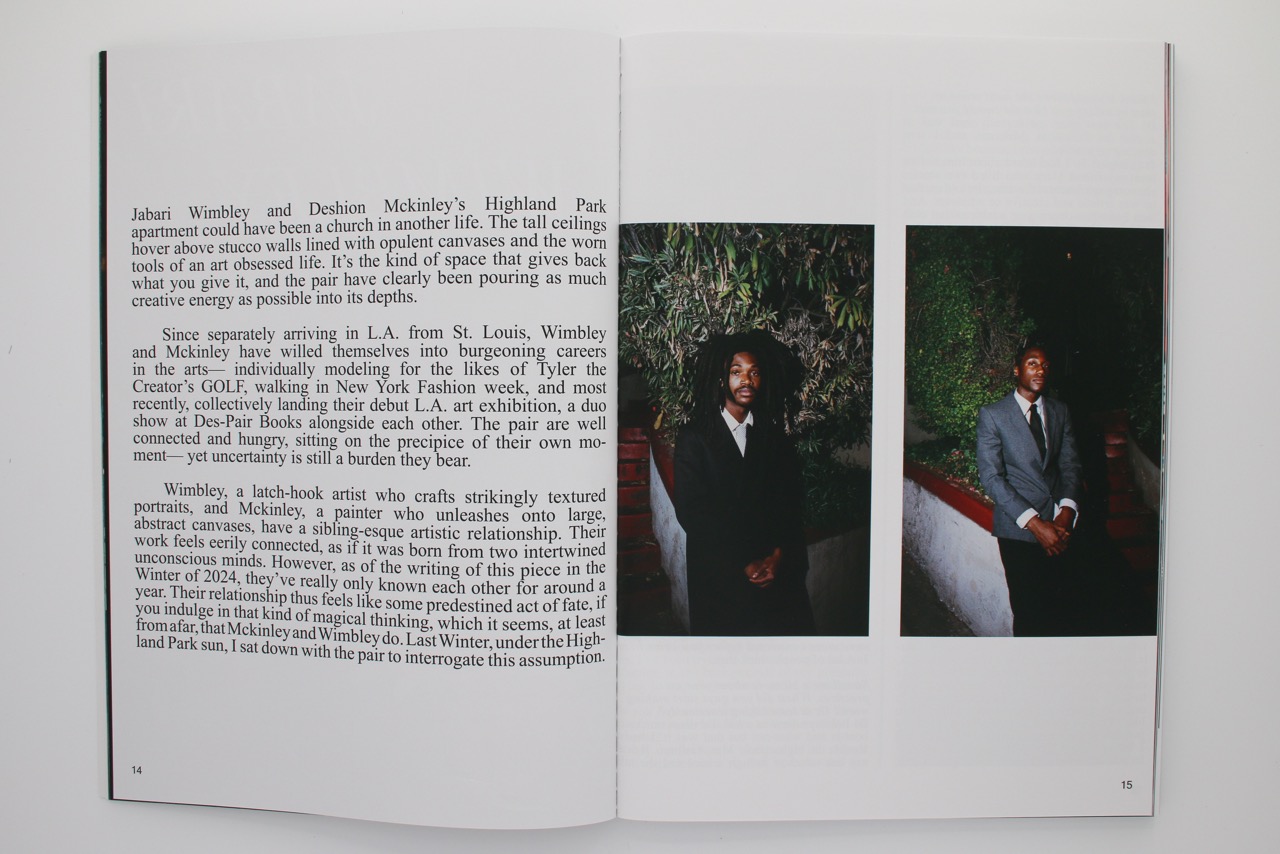

I'm naturally a really quiet person. While I prided myself in doing it all the first time around, I learned that's just not the way of doing it. That was me subconsciously protecting my art I think. Jai Street still reflects my POV but also all these other people I work with. I had no experience creating a magazine and was just learning along the way. I learned that, in a way, collaborating is what creativity is. Building a team has made our work much more sophisticated, nuanced, and honestly more interesting because everyone brings their unique perspective and interests to the table. Our team is not just New York-based. I’ve been working closely with Theo Meranze, a writer in LA who has connected me to many people out there and has been the reason for some of the new faces in the issue. Berlin-based writer and art curator Auguste Schwarcz in Berlin connected me to photographer Julien Tell. He is leading efforts to make our Berlin launch happen. There are many others.

What role has New York City played in all this?

I started Jai Street out of a passion for the creative scene in New York. The first issue was solely New York-based contributors, which was great, but now I see New York as the foundation and I’m focused on expanding outwards. The second issue still has a lot of New York representation, and that's always one of my goals. There's a kind of grittiness to the scene here, where people are really trying to put themselves on and hustle for what they want. There's something beautiful about someone hustling for their first gallery show and finally getting it. That’s something pretty unique to New York in its essence.

Are there any stories in Issue 02 you’re particularly excited about people seeing?

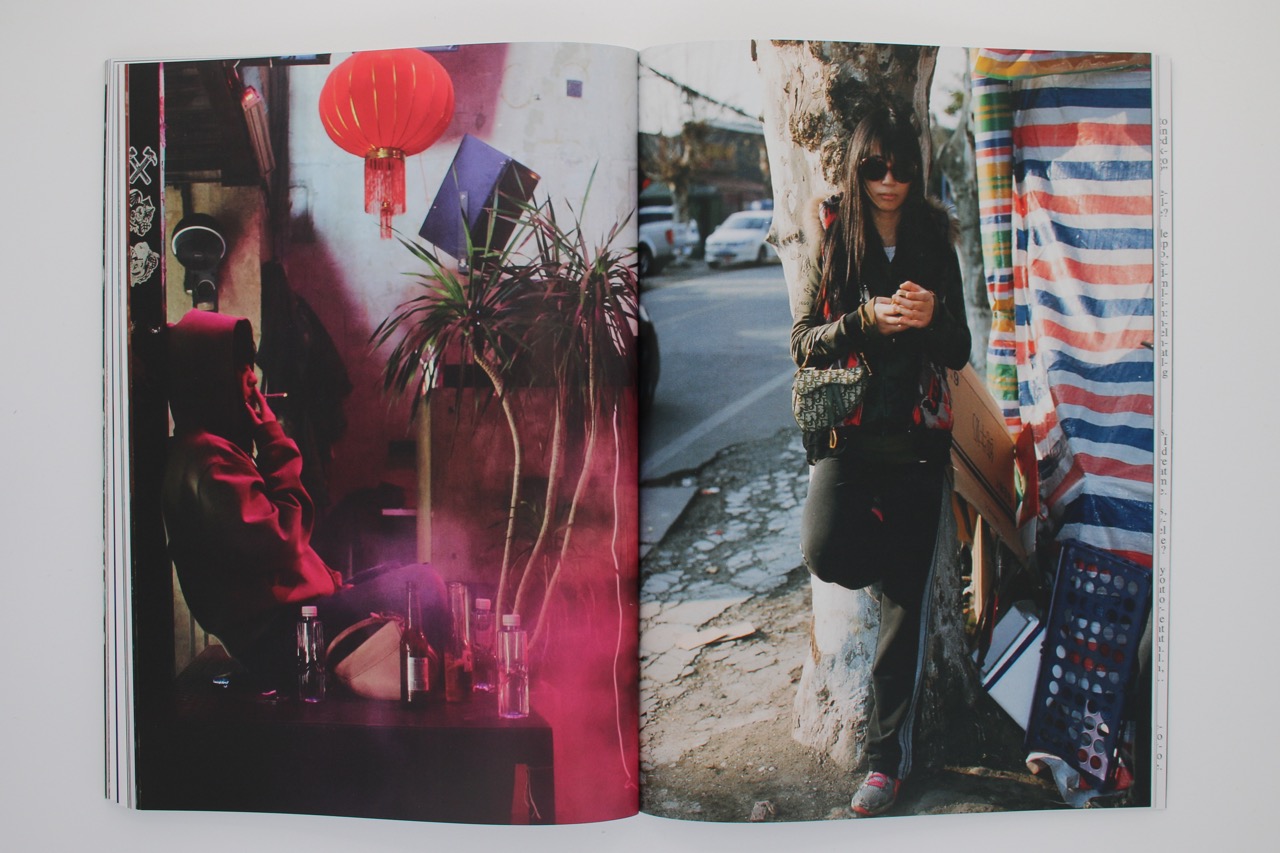

We are publishing a documentary-style photography introspective titled “Return to QiongLai” by Berlin-based fashion photographer Julien Tell in the issue. The series, very atypical to Julien’s traditional work in high fashion, follows a close friend on her trip back to her hometown in China during the Lunar New Year. The series paints a picture of the contrast between China's rural and urban environments, focusing on the life of native farmers in rural Sichuan and the alternative techno club scene of megacity Chengdu. The photos are amazing. The feature is also special because we are presenting and putting on Julien’s first-ever solo show at a gallery space in Berlin featuring these photos at the beginning of August.

We are also doing a story on an Oaxaca, Mexico-based art collective, Yope Projects. The group of six artists are up to big things, having recently shown and curated shows in Los Angeles, New York, and Mexico City, but also shine a light on the greater art community and emerging scene in that particular region of Mexico, known as being the country’s center of traditional craft and commerce.

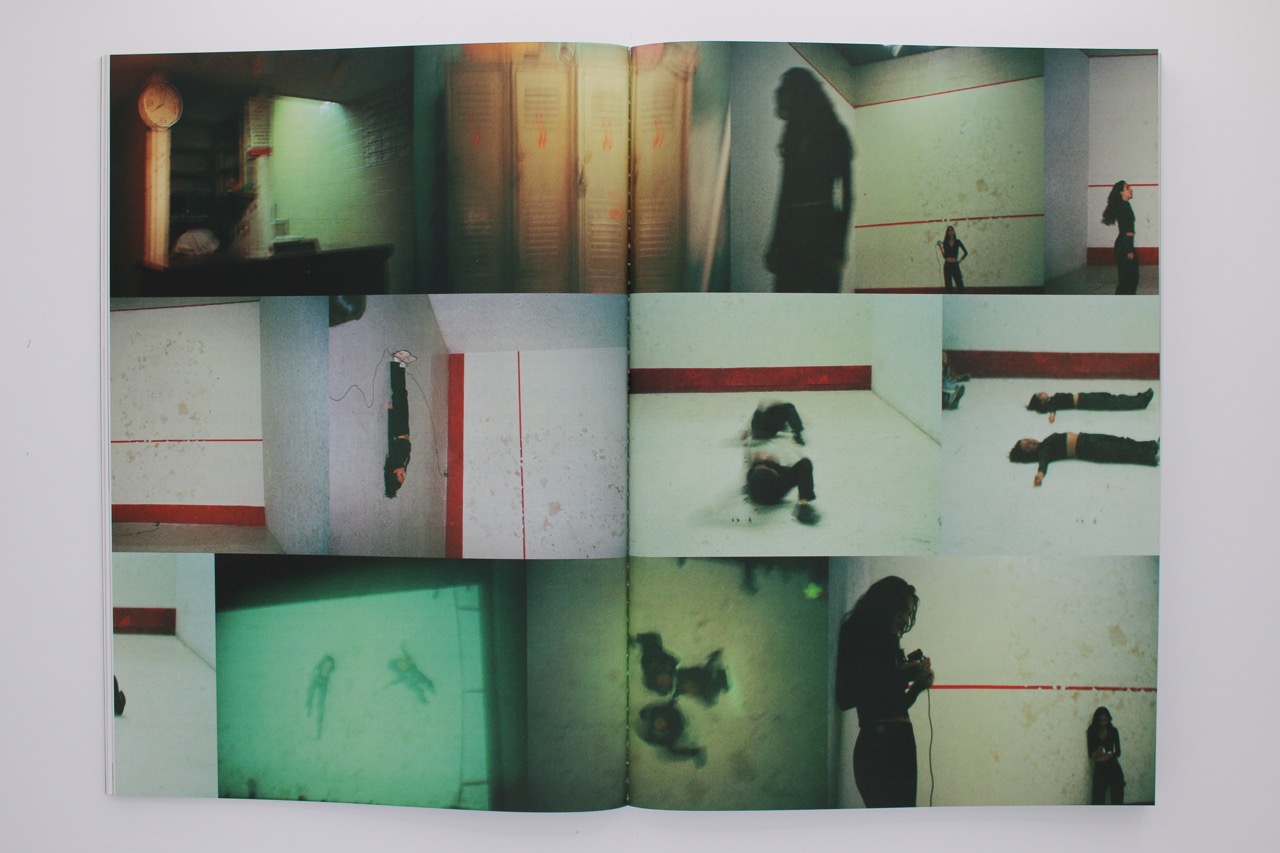

I’m really proud of our story with Isaiah Barr. A New York native, Isaiah's also a musician and founded the art and jazz ensemble Onyx Collective. Isaiah’s yet to have his photography in print and has had an idea to lay out a series of photos he took in succession to replicate a film roll. We made that vision come to life. I thought it would be interesting for Isaiah to pick an interviewer and for them to come up with questions based on their relationship with him. He chose his partner, Renata Pereira Lima.

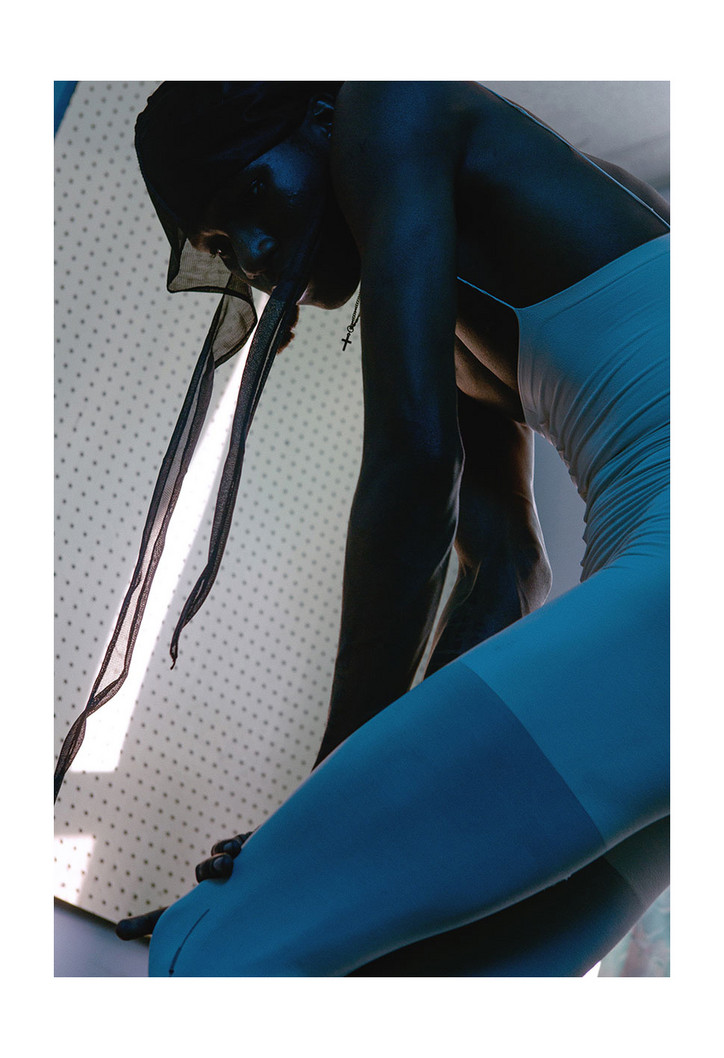

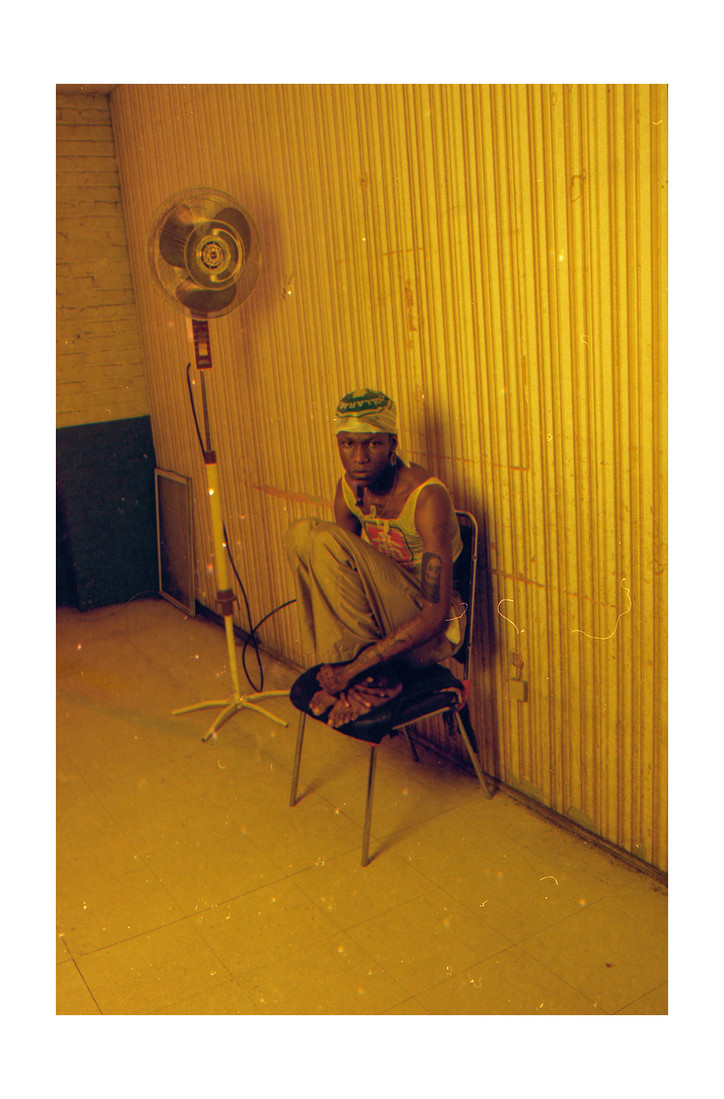

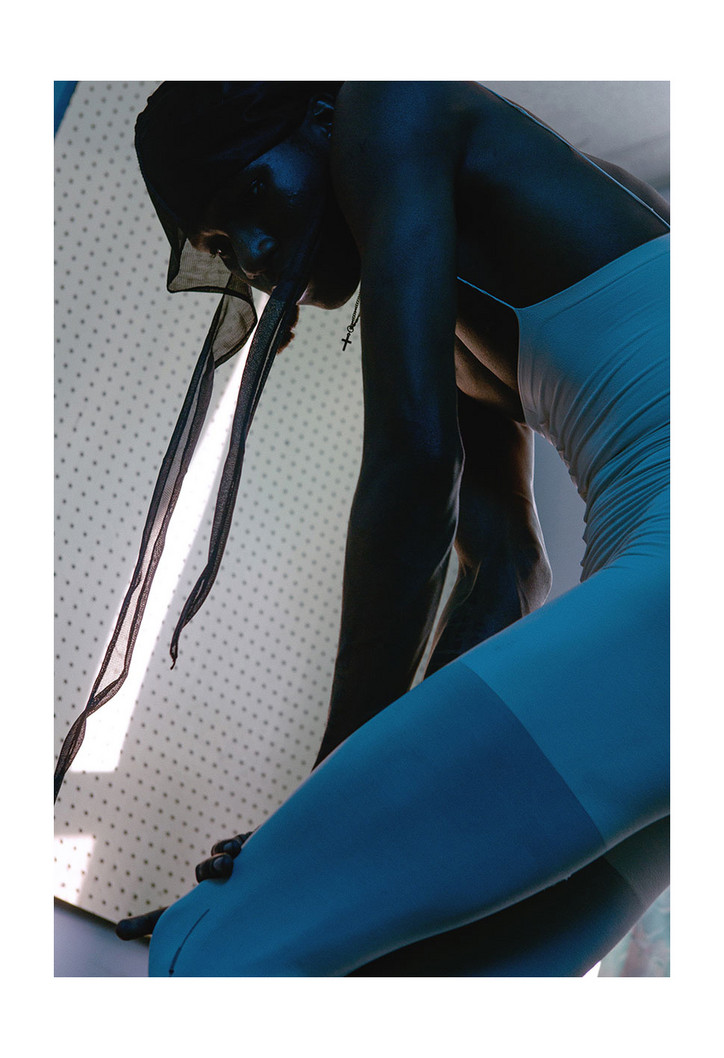

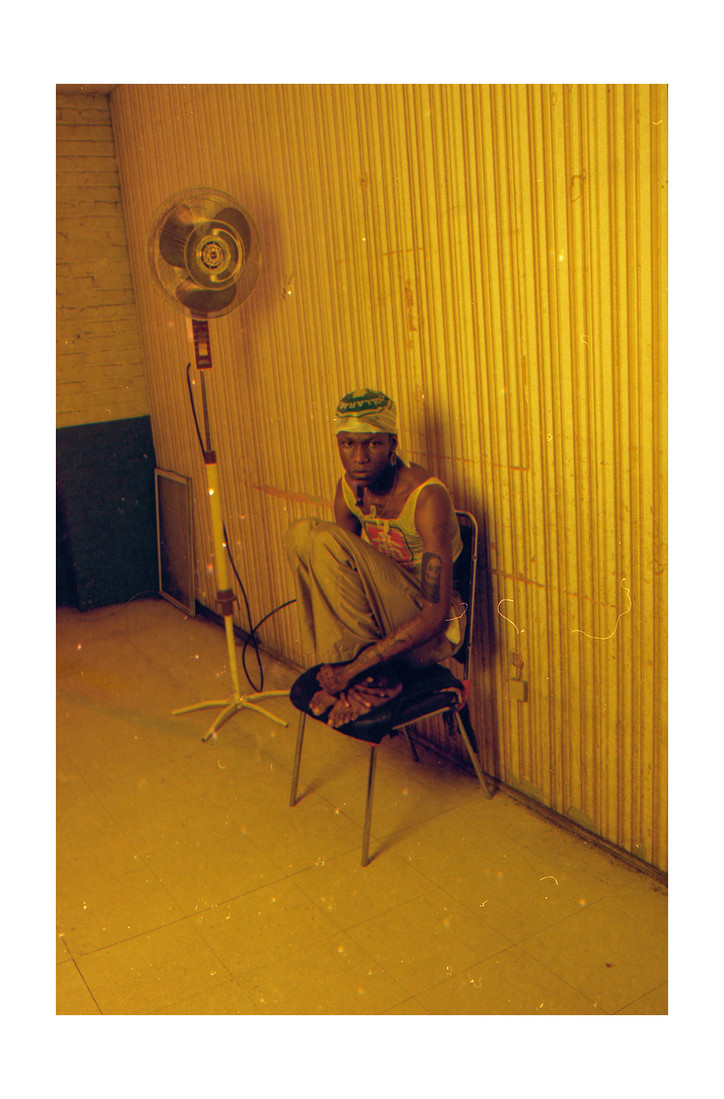

Isaiah Barr, "Dimension Zero"

Do you agree with the notion that print is dead?

I feel like it's the opposite, although it was a bit ironic that you just announced pausing your print magazine. For me, those who appreciate print and everything that comes with it — physically turning pages of a magazine and seeing print as a vehicle for physical design — are still all in. With that being said, the business model of publishing as a print publication is not the greatest. Production costs for high-quality print are high, and distributors and stockists are conservative in who they buy into. They opt for consignment before wholesale given their margins are so small. It’s understandable but something we are trying to work around.

Publishing Issue 02, I’ve learned there’s a balance we have to strike between coming to terms with what, say, a store in Germany can do that may not be as beneficial to us cost-wise, but the flip side is we gain exposure there to a passionate market we wouldn’t otherwise have. We’ve also been fortunate to sign with an international distributor in the UK. The team there has been great in setting a roadmap for getting Issue 02 and the Jai Street name to Europe and Asia, where I think print may be a bit more appreciated and accessible.

As I'm building Jai Street, I'm also defining what the brand stands for and the kinds of stories we tell. The print magazine is our platform right now to do that. We make exceptions in terms of trying to make money off the print magazine to gain exposure. Let's get Jai Street everywhere to build this brand to the point where, in a couple of years, we can create more tangible physical experiences like galleries and group shows. So for me, the magazine is not an endpoint but a jumping-off point.

Looking forward to your next issue, what do you plan on maintaining?

Jai Street is built on an eye for curation. We believe creativity is about how stories are told. I consider myself a storyteller and want to ensure we're focusing on highlighting creatives globally, like the latest issue which features essays, interviews, photography, design, and art representing voices spanning from the clubs of Chengdu, China to design studios in Los Angeles, to back alleys in Tokyo, and back home to New York. Also making sure to feature people that are still on the rise like us. For many, this is their first time having work in print or undergoing a full-length interview and profile of their work. For any artist, that’s exciting and motivating. I think that’s why those features feel very connected to Jai Street and become all-in to what we’re doing.

Shop Jai Street here.

Friday. 3 pm. This is luxury. Friends is on the hotel TV. I’m eating a burger in bed. New York is far behind me. My only worries are the possibly-infected cut on my finger and whether or not wearing my flea market “LADY RIDER” leather vest would make me look like a poser. At the festival, the Veterans Park bartenders know us all intimately. When people tipsily fumble with inserting their credit cards, the bartenders joke about sticking things in the wrong hole. I get my favorite flavor of Smirnoff Ice (that my deli doesn’t even carry). The bartender doesn’t say goodbye — she says “see you later.”

The buffest guy here is worried about getting bloated. “No more lemonade for me,” he resolves. TV got it all wrong about bikers. In any situation, I’d rather go to a biker than a cop. Priscilla Block sings and makes me realize that country songs and my cosmopolitan party-poetry aren’t really that different — we both write about drinking and running into exes. Maybe country music is my fate. Priscilla chats it up with her fans: “I see your wrist. Did you get my signature tattooed on you? I don’t even know if I love my dog that much.”

5 pm. There’s a Zyn tent in the middle of the park. “What the fuck are Zyns?” I hear someone ask. We both turn around to see the line wrap around the tent twice. It’s still light out and one of the Nitro Circus guys is flying off a ramp while seated in a recliner. “Give it up for Tyler Roberts, who is lying on the ground because he just jumped a couch.”

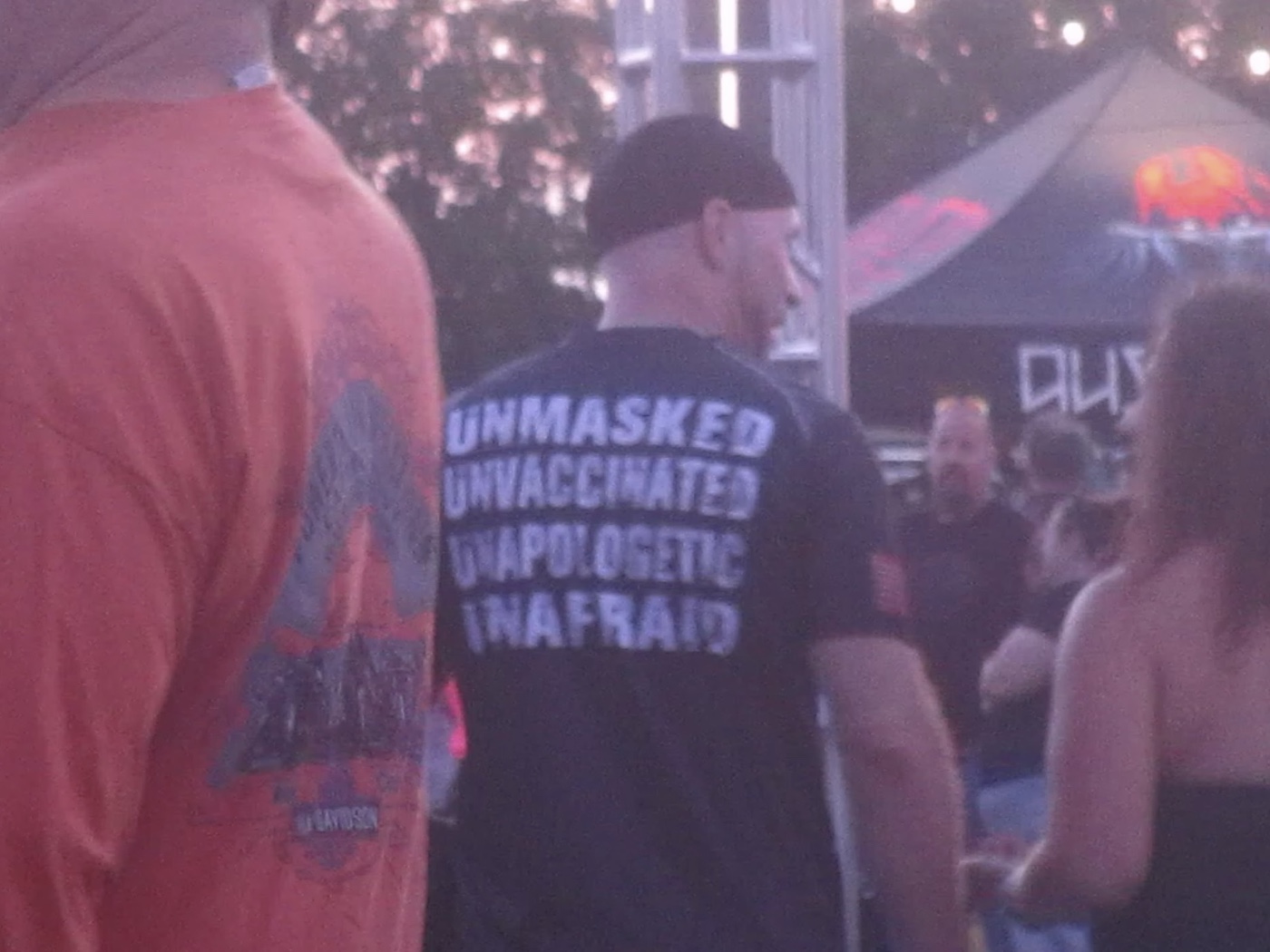

8 pm. HARDY gets real American. “If you’re in this country and you’re not proud of it, FUCK YOU!” Everyone’s booing these hypothetical anti-patriots. I find myself clenching my Smirnoff Ice amidst an emblazoned crowd chanting “USA! USA!” People notice me not chanting. I keep my eyes to the ground and wait for the country music to start.

I’m wondering if I should’ve done pushups in the hotel room when I hear someone behind me ask, “Have you ever been in a mosh pit?” Some kid whose age is definitely still in the single digits answered: “Once.” A girl finds a motorcycle-shaped chip in her bag. Her mom reacts in a way that reminds me of the grilled Cheesus scene from Glee. She claims the Harley chip is a sign from god. The girl eats it without hesitation. Someone hops the fence from GA into VIP. For the first time since that chant we all share a single look of solidarity — a look of ‘I don’t know what the fuck that was but it’s not my business.’

Jelly Roll is on. “God bless America. God bless Milwaukee. God bless the long-haired sons of sinners.” God bless my dead camera. He dedicates his song to “those who tear it down Saturday but still end up in the pews on Sunday.” I think of when I’d leave the club at 3 and end up at my 9 am literature class the next day. “This is for those who love Jesus but still say ‘fuck’ a lot,” says Jelly. He believes that the spirit of rock and roll is with us, here at the Harley Davidson Homecoming. “The spirit of country music is here. The spirit of love is here. God is in Milwaukee. Heaven has a smoking section and an open bar.” A Ziplock bag containing cheese curds and a joint is launched to the stage. It’s an impressive throw. I definitely should’ve done pushups before coming. Jelly gives his ode to weed: “I was only 12 years old when I thought I smelled a skunk in my house. I now know that to be the smell of freedom.”

10 pm. In front of me is a heated argument about spots being stolen. One thing I learned — first from a Patti Smith show earlier this year, then from the Jelly Roll show — don’t mess with middle-aged women’s concert spots. Amidst the arguing, one of the antagonized men turns around to ask me, “Are you here all by your lonesome?” I can barely answer because I’m still shaken from hearing the phrase ‘all by your lonesome’ unironically. His friend turns around to call me cute and ask me for my Snapchat. I haven’t used Snapchat since I was in high school (in Ohio). I’m taken aback because I thought that only girls like Sabrina Carpenter were considered cute in the Midwest.

Machine Gun Kelly rides onstage (in an HD Low Rider ST. Very nice). All weekend, there had been murmurs about his surprise performance of his new song with Jelly. God doesn’t bless my dead camera so I don’t get any pictures of him. Jelly and Kelly debut their song and Kells sings with his emo voice. Jelly thanks the crowd: “You guys took the most average, overweight, white trash guy in America and made him a star.” Jelly shouts out his guitarist — it’s apparently his 57th birthday. “He’s the only person onstage with a good credit score.” Considering all my apartment applications that just got denied, I can’t say the same. “He’s also always the drunkest person onstage.” I find common ground.

The older couple next to me taps my shoulder: “You’re young. Who’s that young, skinny fellow next to Jelly?”

“That’s Machine Gun Kelly.”

“And who’s that MGK that Jelly keeps talking about?”

“They’re the same guy — MGK is just his initials.”

“Oh! He’s quite good. He should be famous.”

A six-year-old boy tears a beer can in half. The burly guy in front of me is wearing a tail. America the beautiful.

Saturday. 12pm. I haven’t taken my meds yet so I’ll take them with some free brisket and an alcoholic beverage like America’s god intended. I ask the bartender if it’s too early for a Twisted Tea. “It’s never too early for a Twisted Tea,” they reply. Truer words have never been spoken.

I’m wearing my vest. Goddammit if I’m a poser. My mullet is wild and beautiful. My cut is definitely infected. While I’m watching the ride-ins, someone from the news tells me they love my look and asks for a photo of me with my bike. “Sorry, I didn’t actually ride here. I just dress like this.” I resolve to pay my loans, get my bike license, get a bike, and ride into next year’s Homecoming to redeem myself. I spend my time in between shows at Nitro Circus, high-fiving the bikers and wondering if I could even pull any of this off in Skate 3.

6 pm. “Welcome back to the party, motherfuckers!” Cypress Hill is on and I can’t tell if the big cloud of smoke is weed or a fog machine. Probably both. Weed isn’t legal in Milwaukee. Rock on, Harley Homecoming. Joint in hand, Sen Dog grants DJ Muggs the title of Greatest DJ In The World. And apologies to all my friends reading this, you guys do not compete for that title. “Are you feeling the vibes right now? Are you feeling alive right now? Are you feeling high right now?” asks B-Real. I make eye contact with Sen Dog on my way to do some shots with some bikers.

A photographer comes around and has Alex and Stu put me on their shoulders for a photo. Very few words are exchanged before I’m up in the air.

The Offspring comes on. “Milwaukee is a mecca to a beer drinker like me,” says Noodles. “Thanks for being here instead of the beer tent.” All 60,000 of us collectively regress to our pop-punk phases. I say ‘phase’ like it ever ended, but it’s 2024 and I am two-stepping in Doc Martens and holding a digital camera while they play “You’re Gonna Go Far, Kid.” Apparently that song just hit one billion streams. “We got like, 200 bucks from that,” says Noodles.

They debut their new song and Noodles tells us, “That is the best we’ve ever played that song. Dexter left it all out there. He really nailed parts of that song.” “Parts of songs are my specialty,” says Dexter. Noodles says something about getting turned on. “It’s like we have a choir of earthbound angels.” He’s talking about us. “Do you know why they’re earthbound? Because they’re a little bit naughty. This is an audience that loves their curse words. Would you guys like to sing and cuss with us?” Dexter says this audience is the best thing that happened to rock and roll.

9 pm. Red Hot Chili Peppers are here. This is the band that all my friends in bands want to be. They bring out Willie G, who’s nearing 50 years at Harley Davidson. Anthony Kiedis is in a cowboy hat. “Take off your shirt!” a man behind me yells. I turn to give them a nod of understanding. “He wants a husband,” his friend explains. Good luck, man. Beach balls are bouncing around. There is no hatred in the crowd right now. I’m content watching the stage through the neck rolls of the guy in front of me. There’s a guitar and bass solo that brings me to tears. Fireworks go off. No one notices. Many of us are listening with our eyes closed, tired and heat-stricken, but willing to bask in the light of Flea, jumping around in a skirt.

1 am. I end up meeting that guy from the night before. Do it for the plot. We did the things you do in the Midwest — drive to the gas station and buy hot food. We waste gas to keep the conversation going.

Sunday. 9 am. Waiting for my flight, there are two guys next to me at the gate who see me editing photos — they’re decked out in Harley merch and cowboy hats, I can only assume they’re coming from the festival. “HARDY was whacked out that night.” Oh yeah. Definitely coming from the festival.

Working alongside Bryn Silverman and a cast of other collaborators, Dennison illuminates the intention and legacy of Black people's ability to play with the legend of the wind.

Silverman, who calls the production of this project "shockingly smooth," spoke to the abundant donations of equipment, cast, and time that were contributed to the filming process.The local film community made it all possible. "We also just had a spirit of working with local Louisville filmmakers and crew. Everything was so community-driven, which made things a breeze, and we were just so supported," she says. The Black skate community of Louisville also welcomed the film and crew with open arms "It was really heartwarming to be welcomed into this community,” Silverman adds, “especially because I didn't grow up skating."

office sat down with Dennison to discuss the film's focus on sound production, jazz, and playing with spiritual knowledge as a means to begin.

Clarissa Brooks— I wanted to jump into something specific. There is a scene where all the members of the 502 Crew are lying down on the floor and are shot from above. What inspired that shot, and can you talk more about the intimacy of that moment?

Imani Dennison— I love this question. Also, I wanted to add that this film is about Louisville being a segregated city and still is. That trajectory and how Black people have been building community and having it ripped from them and also just navigating the segregated South — I mean, even today in 2024. As much as this film is about imagination, it is definitely about resistance, resilience, and overcoming structural racism in a segregated city and a small town, especially.

In choosing to have the 502 crew lay on the ground for their interview, I wanted them to feel comfortable, and I didn't like the interview to feel stiff. I'm not a fan of talking head style interviews; for theirs, I wanted them to feel their most comfortable and vulnerable, too. We know that connecting with the ground helps soothe anxiety and helps people ground into their bodies a little easier like having the ground have their back and having their brothers on each side felt appropriate.

It reminds me of the couple [Laneisha Beasley & Markice Armstrong Sr.] towards the end of the film whose shoes are off and are comfortable on the couch as they do their interview…

Yeah, that's the same concept: be on the couch, no stiff interviews when talking about why something is special to you. I wanted that couple to feel at home when communicating to the world about this community that they helped build and are also a part of. Having that intimacy felt important.

Are these folks that you've known for a long time, or have you built relationships with everyone throughout making this film?

I started an iteration of this project in 2020 when the pandemic hit, and I moved back home for eight months and got a small grant to make a film about my hometown. I made a 9-minute proof of concept of what we see today called The Roost. So, with some of the folks in the film, my initial contact was in 2020, but I loosely kept in touch and let them know I was still working on getting more funds, but Jordan [from the 502 crew] and I grew up in the same neighborhood, and even though we weren't close we knew of each for awhile. It's a very tight-knit community, and folks were really trusting, which is excellent because reception and trust are everything.

I would love to hear more about your rituals when you begin a project. What does it look like in your world?

Conceptually, when I have an idea in my head, in my body, or in my spirit, it usually starts with music. I make a playlist that narrates or guides me into images, so I start going online and sourcing images in my head, and I make a folder of them. Step one is always sound to me. I start thinking about that immediately, and I'm a wormhole type of person, so I'll be up at 4 am just looking up stuff. Sometimes, that process is lengthy, especially with documentaries. I usually follow more than leading, relinquishing control, and following wherever it takes me. I ask myself what I am trying to say and research those words and phrases as I go along. Research is a massive part of my practice, and with this work, I knew I had to focus on my hometown story, and I started asking myself, well, who am I? What were my rituals as a teenager? What do I want people to know about Kentucky and Louisville? A ritual for me as a teenager was roller skating every Friday. I wanted people to know about this community and how it makes people feel, and I tied it to folklore, in this case, The Flying Africans, because it has so many roots in how Black folks have survived through storytelling.

What role does your work at Black Science Fiction play in the sound production of this film?

BSF and just the ethos of Black experimentation significantly impacted the project, as they always do for me as a maker and storyteller in this process. Aquiles Navarro did the sound score for TPCF, and he's a band member of Irreversible Entanglements. I knew I wanted him to be a part of this project early on. He gets it. He's played a show for Black science fiction before, but I think the work of BSF pours into this project by playing with free jazz, improv, and just experimenting with sound. Sun Ra plays a big part in this; he's the Afrofuturist. He's definitely an inspiration, and even though the film is named after the story The People Could Fly, it's also a myth, and similarly, BSF is playing with mythology. It all exists in the same universe.

Keiyaa's song [I Want My Things] , someone who has also played at BSF a few times, and she is also just a musician that I admire. That song, in particular, is so much about the reclaiming of things, which was necessary at the end of this film; I honestly didn't want the movie to end with any other song but that one. It was so perfect and tied to everything that I was like whatever we have to do to get it, let's get this song. It's just so good for the film.

Laura Sofia Perez, a friend from Puerto Rico, did sound design, so she and Navarro collaborated to make the sonics of the film, one of the many ways that we pay homage to the diaspora.

Do you have a favorite scene in the film?

It's gonna be the scene "Imagination" for me. It's the scene where the Sun Ra song "Imagination" plays, and the 502 crew is just doing their thing. They have on these Jabbawockeez masks that they used to wear when they were teenagers. In post-production, our editors manipulated that scene for motion under my direction so it could feel chaotic. I wanted us to play with time along with having the rights to have Sun Rain the film. It just felt right to make that call.

When was the last time that you skated?

The last time I skated was actually when I filmed the film. We did have a camera operator who wasn't on skates, but for a lot of the things you see where the shot is on the wood, it was me on my camcorder and just on skates doing my best. I grew up skating so much, and it makes you brave and daring; it definitely awakens my inner child, and yeah I love it so much.

The People Could Fly debuts at BlackStar Film Festival on August 3rd at 8pm ET at the Kimmel Center in Philadelphia, PA.