On Monuments

His pseudo-realist installations, which involve colonist statues covered in South American ponchos, grand statues of horse-riding conquerors, sans-the-conqueror, and flaccid depictions of obelisks drained of their origin, stand in defiant contrast to colonial imaginations of superiority and divine greatness. And, at the end of the day, he seems to just be having fun with it.

His show, On Monuments, is on display at Perrotin’s Viewing Salon through November 6th. Iván and I spoke over email about Parisian rain, t-rex sized pigeons, and being a cultural entity.

Left — Turistas (King Charles III of Spain),2013. C-print. Unframed: 160 x 120 cm | 63 x 47 1/4 in. Framed: 165 x 125 x 5 cm | 64 15/16 x 49 3/16 x 1 15/16 in. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

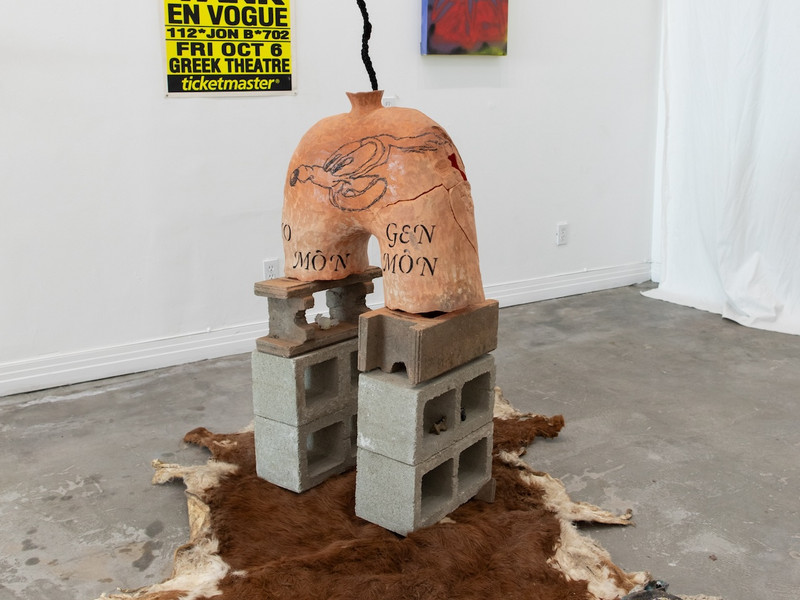

Right — Empire, 2020. Concrete, wood, gold leaf. 211 x 124 x 55 cm | 83 1/16 x 48 13/16 x 21 5/8 in. Photographer: Tanguy Beurdeley. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

Hi Iván, how are you doing?

Good!

Where are you now?

In my studio, in the north of Paris, in the office. It’s raining today.

What has been on your mind?

Oh, so many things. I’ve been thinking about a public commission, of which I’m a finalist, for the Urbanism Research Center in Marseille. I want to create something inspired by Trisha Brown's performance, titled Roof Piece. I’ve been thinking about a new way to manage my studio—my studio manager left and we just hired a new person. I want to change the way we work, maybe collaborate more with other teams. My girlfriend and I are thinking about moving to a bigger apartment. I’ve been thinking about Covid, and that it will likely last. Thinking about my family in Colombia; it’s very difficult right now, violence has increased, the government is negligent and corrupt. I’ve been thinking about the US election.

What are you working on now?

Beside the Marseille project, I’ve been planning for my next solo show at Perrotin New York (September 2021), which will be a continuation of our Viewing Salon, On Monuments — a reflection on the value, use, and pertinence of monuments. I want to generate proposals for a critical approach to monuments, monuments that criticize themselves. I am also working on a solo show at Dortmund Kunstverein, where we will organize protests every week.

I am working on a public commission for Sciences Po (Political Science School in Paris)—six massive concrete arches with the text engraved. Also, a commission for a public park in Berlin—a large-scale permanent project, consisting of different bridges around the park, so I am in touch with engineers and landscape artists solving some details of the project. Lastly, I was picked as a finalist for the Plinth project on the Highline in New York—I proposed a pigeon in the scale of a Tyrannosaurus Rex (20 ft high), so I’ve been scanning pigeons in 3D and creating a model about two feet high, that’s a funny one.

Left — Horse (New York, Union Square), 2011. C-print. Framed: 70 x 50 cm. | 27 1/2 x 19 3/4 in. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

Top right — Etcétéra: en couvrant avec des miroirs Francisco de Orellana, le soi-disant découvreur de l’Amazonie. Parc national, Bogotá (Etcétera: Cubriendo con espejos a Francisco de Orellana, supuesto descubridor del Amazonas. Parque Nacional, Bogotá),2012 – 2018.

C-print. Unframed: 158 x 158 cm | 62 3/16 x 62 3/16 in. Framed: 161 x 161 x 5 cm | 63 3/8 x 63 3/8 x 1 15/16 in. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

Bottom right — Horse (Paris, Louvre), 2011. C-print. Framed: 70 x 50 cm. | 27 1/2 x 19 3/4 in. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

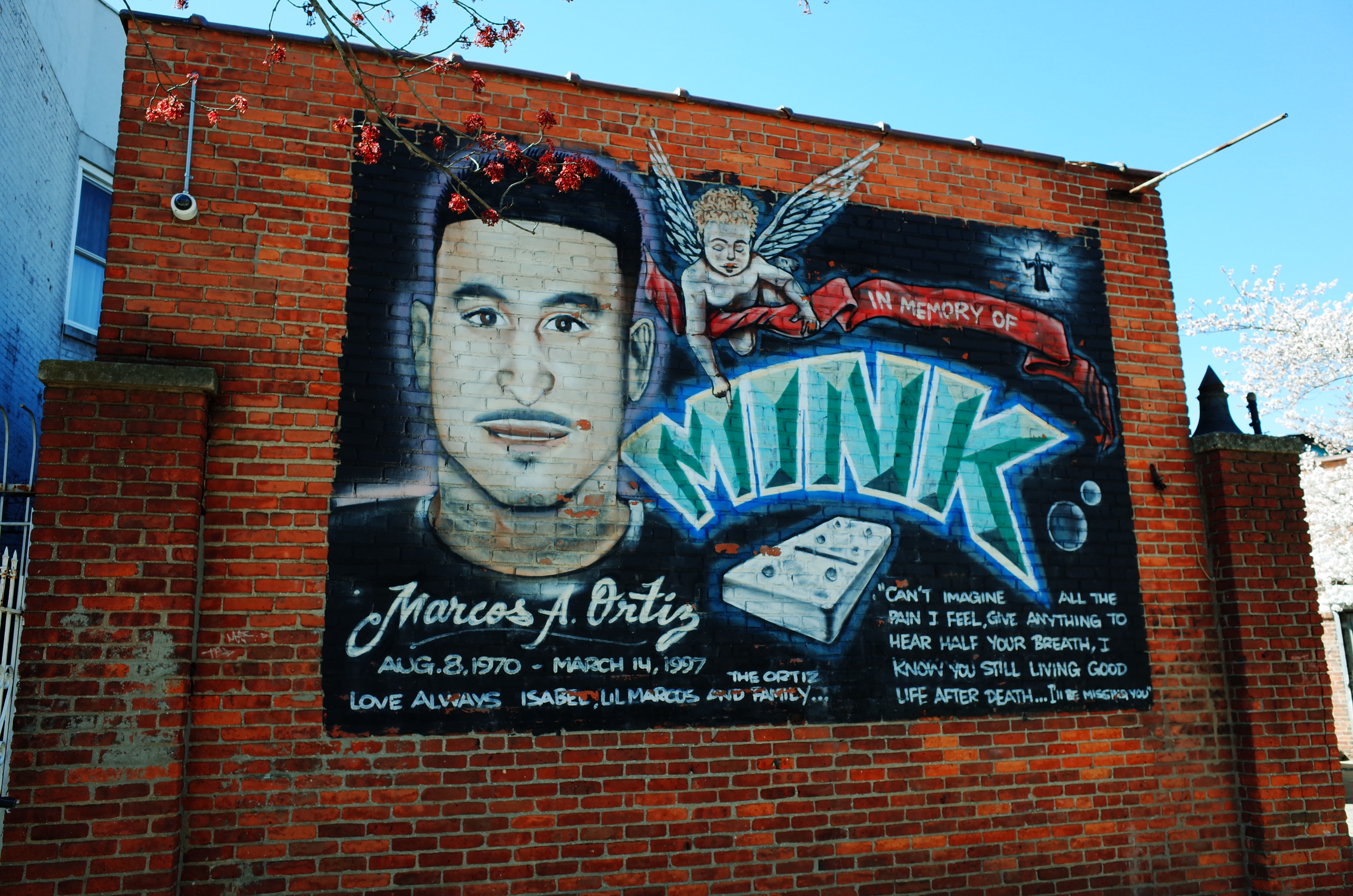

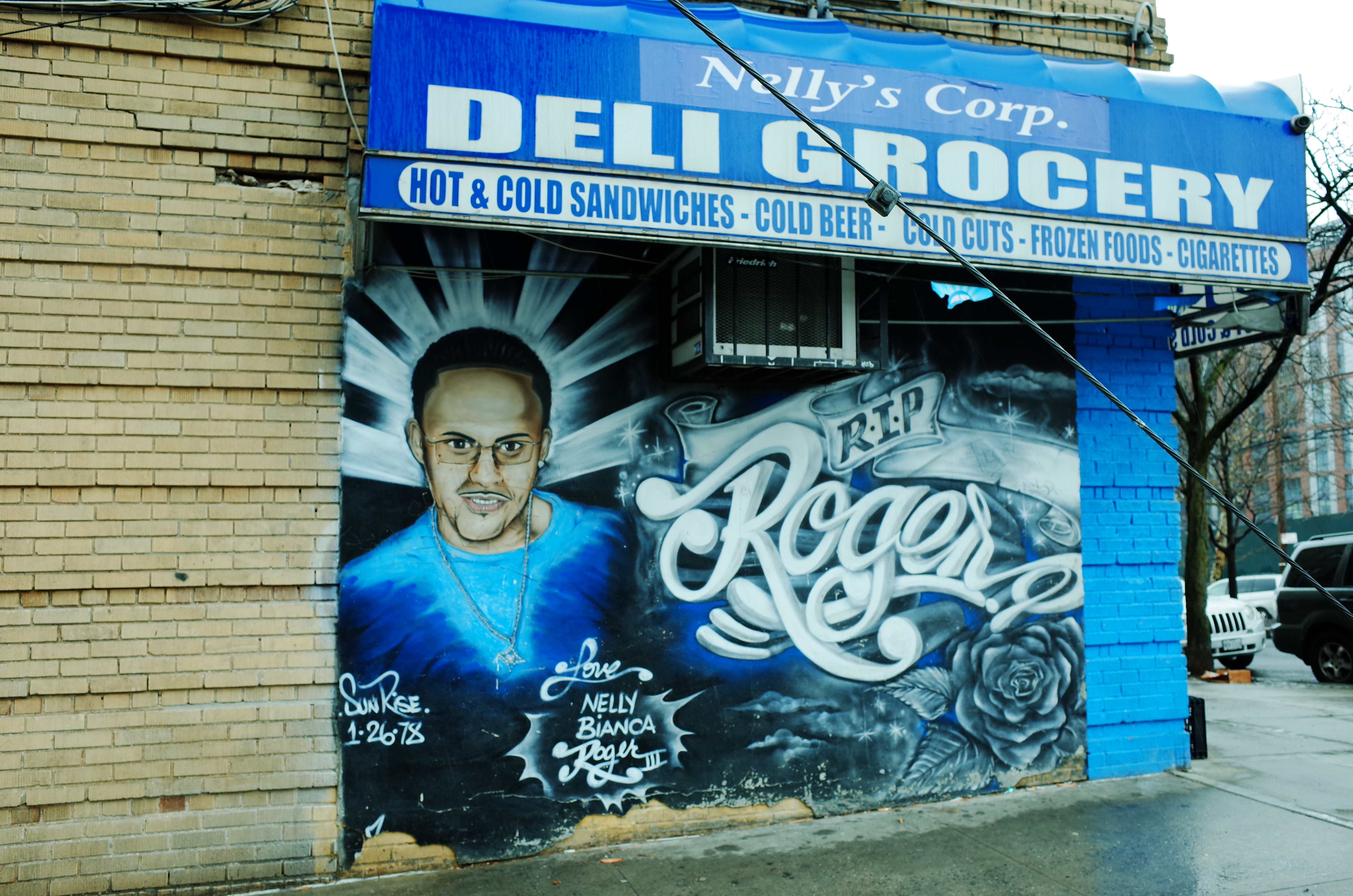

I had the pleasure of looking through your works in the Perrotin viewing salon with the On Monuments series. You’ve been engaging and negotiating with the idea of the monument for years, but the world had a recent reckoning with monuments over the summer with the Black Lives Matter movements as those in the Americas and Europe vandalized and destroyed monuments to colonial settlers. How did you react to this movement? How did you feel it connected with your work?

Well, the idea of monuments and their meaning is something I have been focused on for the past fifteen years. So, when I saw the current movement going this way, I was very glad. I feel we need to be more critical not only towards the monuments that exist but also towards the idea of the monument itself. Lectures on history and governments' narratives need to include critical teaching. We cannot continue simply adulating our supposed heroes, we need to have a critical lens on our own past if we want to conciliate our present and create a more inclusive future.

Clearly, ‘Monuments’ is a theme that has permeated throughout your works for years. What is a monument to you? Does the power of a monument change for you within its context and environment? What monuments would you like to see in the world?

Historically, monuments have been created to write a certain history into our urbanscapes—they celebrate power, a particular vision; they are propaganda. I feel we should have conversations, create negotiations, modifications to the monuments that exist, and create others that contribute to a different narrative, different perspective. For example, Christopher Columbus… I don’t feel we need to take down Columbus’s sculptures, I feel the sculpture should be changed, moved, or that other sculptures should be added—texts, objects, different kinds of interventions, so we can include the perspective of people who feel he represents the abuse, slavery, and domination of American colonization.

I also had the great pleasure of reading through your book, Let’s Write a History of Hopes, and it mentioned that you grew up in one of the communes formed in Bogotá during the Colombian revolution, and I read somewhere else that your father was a part of the revolution. How did experiencing revolution during your formative years, especially a leftist revolution, influence your practice?

I grew up in a very politically engaged family, true believers of change, and yes, revolution. I learned as a kid that there were many unfair things in the world—against the most fragile and humble people, but also against indigenous communities, Black communities, women, LGBTQ communities. My family talked to me about colonization and about different religions with a critical eye (we are atheist). This was since I was four or five years old. It was truly the way I was raised. For example, my family’s passion is to talk about macro and microeconomics—my mother is an economist, my father an elected politician—we talk, argue, and also have fun talking about all this. So, of course, I see the world with that filter. My years, experiences, travels, and the people I have met have given nuances to that. I have enriched or changed some visions, maybe elaborated on others in a more precise way.

Left — Turistas (Carlos I de España 5 de Alemania, Madrid, Parque el Retiro), 2012. C-print.Unframed: 160 x 120 cm | 63 x 47 1/4 in. Framed: 165 x 125 x 5 cm | 64 15/16 x 49 3/16 x 1 15/16 in. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

Right — Horse (Paris, Pont Neuf), 2011. C-print. Framed: 70 x 50 cm. | 27 1/2 x 19 3/4 in. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

There are many people, whom I believe are wrong, that believe that political art or political art installations are not art. What are your views on politics in art?

All art is political, all activity is political. Everything we do is an action and a decision that has to do with politics. Some art purposefully deals with political or historical issues. Art, for me, is a philosophical tool—we generate questions and think about the way in which we understand the world, our emotions, our ideas. That has to do with politics. I feel all different types of art are important, it is not one kind or another. Those who say that art shouldn’t be political are maybe afraid to question their own ideas and vision.

What have been your favorite reactions to your monument installations, both positive and negative?

Sometimes, I manage to have complicity from police officers. In Spain, for example, I was putting South American ponchos on statues of Spanish Kings in Parque el Retiro. After I put four ponchos on these big statues, the police showed up. I was on a statue and we started having a conversation, I made a joke. I said I was putting the ponchos on because it was too cold, it was winter. We laughed, and then for two to three minutes, we had a serious conversation about our feelings on the relationship between Spain and Latin America. Then, they asked me to remove the ponchos and let me go. Some rare times I have had problems, but most of the time I end up meeting people, like in Spain, talking about monuments, sometimes in a serious tone, sometimes laughing. Recently a guy insulted me in Nice because I climbed up and hugged a statue. They are very conservative down there.

Where would you like the future of art criticism and discourse to go? How would you want to influence that discussion?

I feel that sometimes in the arts we talk a lot about ourselves. I feel, instead, we need to open the debate and be part of larger conversations. I don’t know if I can influence that, but I feel we should make an effort to use this tool, art, to explore and contribute to other fields. In the way we educate in schools, in the way we conceive our histories, in the way we organize our cities and economies. I believe culture precedes economy. I mean, I feel culture is at the base of everything, before being ‘economical’ entities we are ‘cultural’ entities. Today, in a general way, we think of the economy at the center of everything and that’s a sophism. We generate economies with our cultural behaviors. I feel we can generate change working on culture, thinking about culture in a deeper and more profound way than “cultural activities,” understanding that culture is the engine of our societies.