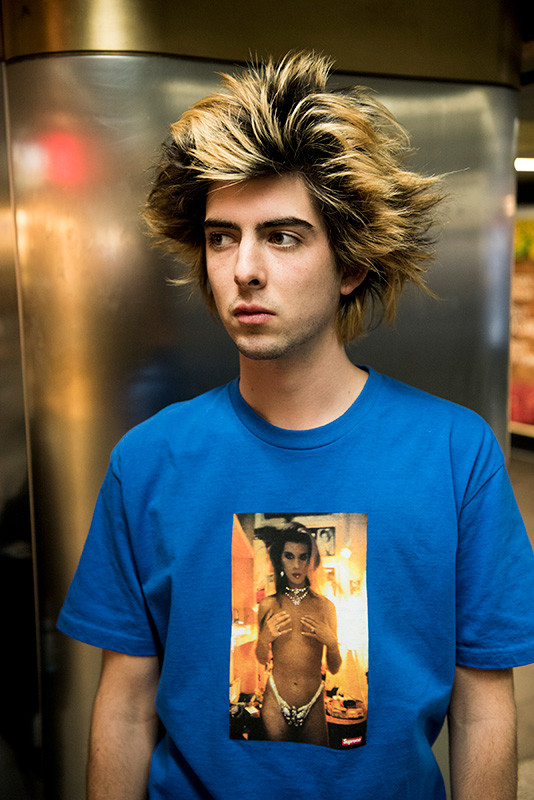

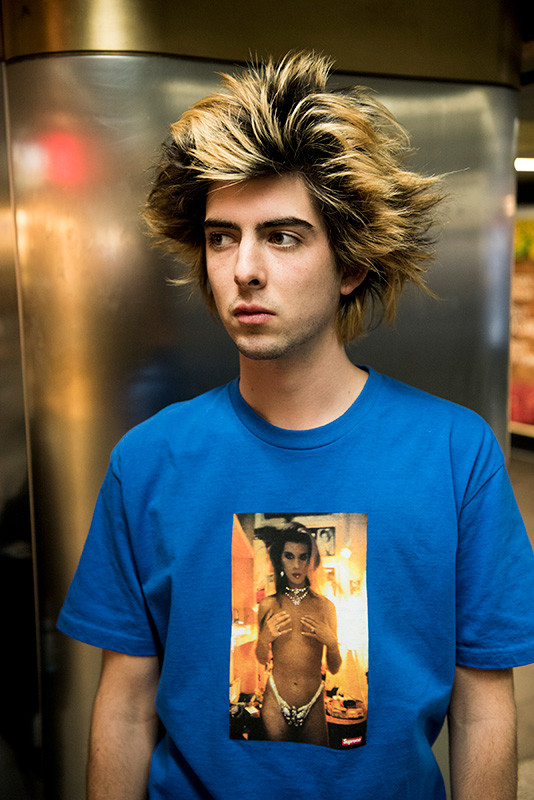

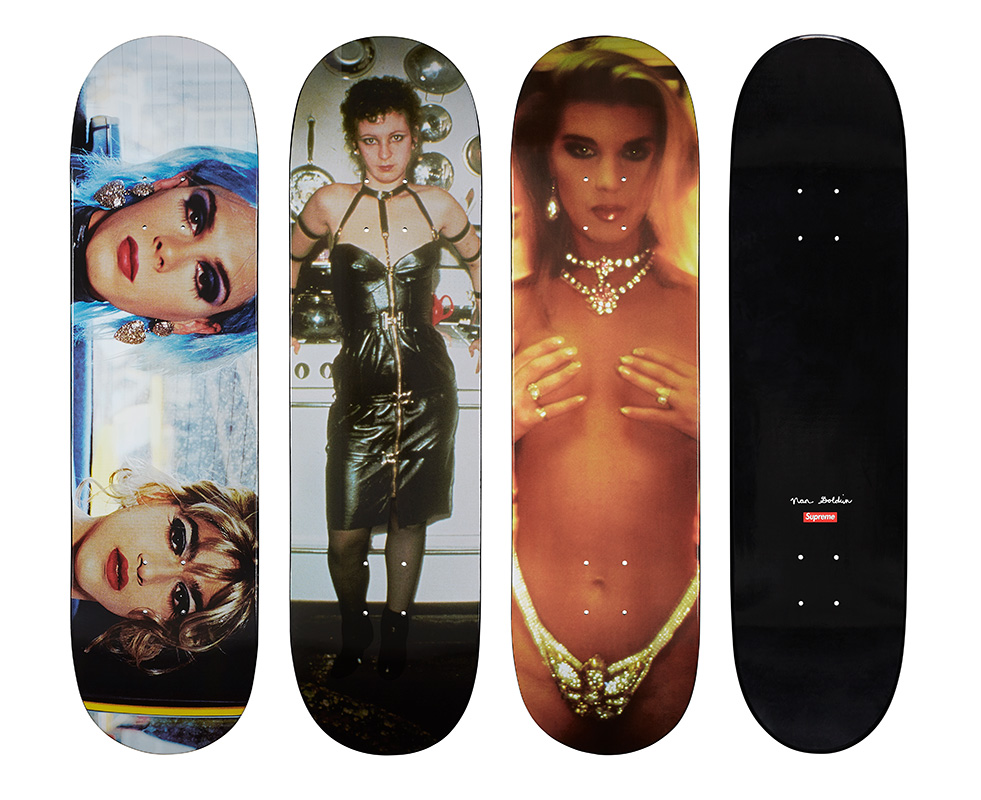

Nan Goldin Goes Supreme

Check it out now, and then go buy your camping supplies before it drops on Thursday March 29th.

Images courtesy of Supreme

Stay informed on our latest news!

Check it out now, and then go buy your camping supplies before it drops on Thursday March 29th.

Images courtesy of Supreme

Supported by Converse, a beloved skate shoe brand for close to a century, the exhibition goes beyond a mere display; it features a built-in mini ramp that invites the local skating community to become part of this historic exhibition. Speaking to guests at the opening, I’d found out that Olivares, Converse, and the Design Museum had extended invites to Melanin Skate Gals & Pals, a London-based collective for BPOC, queer, and neurodivergent riders who redefine what it means to be a skater, empowering communities in an industry that is historically predominantly white and male-dominated. “Skateboard” is a gift to the community. Bringing high-brow appreciation to what’s been unfairly deemed a “low-end” sport, “Skateboard” is a communal declaration, saying “look at me now” to everyone who previously disregarded skating. “It’s not every day you get to skate in a museum,” says Converse skater Louie Lopez, knowing that skating even on the steps of a museum would typically result in a call-in to the local precinct. Ironically, he says this standing next to fellow Converse skater Alexis Sablone, who just last year skated the Guggenheim. For those who understand, skateboarding deserves to be memorialized. Olivares says it best, “It’s art, it’s performance, it’s an 80 billion dollar industry that started with some teenagers loitering.”

Charles Eames’ quote, “Take your pleasure seriously,” colors Olivares’ dedication to combining design and skateboarding, two passions that define his life. He recognizes the deep interplay between “the skateboard, the skateboarder, and the built environment”, acknowledging how this dance advances the game. There’s a shared creativity in both skateboarding and design, as skaters instinctively adapt to their surroundings and transform public spaces into playgrounds. To Olivares, a design project is like a skate session: competitive in nature and progressive in results. “Innovation triggers progress in skateboarding, and progress in skateboarding demands innovation,” he says.

The "Skateboard" exhibition is a treasure trove of skateboarding history, featuring rare memorabilia that spans from the earliest days of skateboarding to recent memory — the first-ever plank of wood on wheels (Louie’s favorite), Tony Hawk’s first pro board, and Lonnie Toft’s (unimaginably and comically large) 10-inch 8-wheeler. There are magazines and tapes that the Converse team has on their childhood bookshelves. Alexis Sablone talks about walking through the physical timeline, saying, “I can point to the exact year that I started skating. Stuff gets really familiar.”

Converse and Olivares address the questions of purpose and audience, while simultaneously giving back to their community in a quiet, unassuming, and honorable manner. Moreover, the mini ramp, constructed by Betongpark, a renowned European skatepark designers, will be donated to a local park at the end of the exhibition, a testament to the commitment of Converse and the London Design Museum to making art and design truly accessible and welcoming. The experience was completely unpretentious. At a dinner in celebration of the exhibit, we exchanged injury stories and the pain of being thirty and getting called “sir” at the park. At the opening, Olivares paused during his speech to make sure that he could say “fuck” (he could). Photographers were good sports when their cameras were knocked out of their hands by flying boards and exhibit workers were only slightly worried when someone on the Converse team (who will remain anonymous) accidentally dislodged a TV that was next to the ramp. It was all in good fun.

office— Why London?

Jonathan Olivares— When I came up in design in college, I would visit London and I would always go to the Design Museum– it was in a different location back then. And for me, the Design Museum was my mecca — even more than the Triennale in Milan, more than the Art Déco in Paris, more than the Cooper Hewitt in New York. To me, the Design Museum was the museum. I would go every time I came to London– I would travel to London in part just to go to the Museum. Then I moved here about a decade ago and I befriended Justin Mcgee who has been one of the chief curators here. And when I thought about where should we do this, my top choice was the London Design Museum because I wanted it to take place in a design context — because I’m a designer and that’s my discipline. That’s my world, that’s where my colleagues are, and that's really where my work takes place. I wanted to import this world [of skateboarding] and stitch them together.

Also on a personal level, skateboarding and design were always divorced for me, but this was me realizing that my education in design started in 1992 when I picked up a skateboard. I learned about hardware, how to put a board together, how to build a launch ramp, how to photograph my friends, how to video my fiends. I was absorbing architecture skating through museums in Cambridge, at the foot of Henry Cobb. I learned that the Christian Science Plazain boston was designed by I.M Pei — I grew up skating there and visually, it was one of my favorite skate spots. It was the hardest to skate — there wasn’t a lot you could do. But I just loved being there. And with hip hop, it was a whole aesthetic culture. My design education started back then. Everybody leaves skateboarding with something different — I left skateboarding with design. So to bring that back here, and to talk about skating as a metaphor for design, for me is really important.

That’s pretty punk — to say, “my design education didn’t start in the institution, it started on the sidewalk, it started when I was getting chased out of places by cops…”

One hundred percent.

And I don’t know if you did that on purpose, but to have a skateboarding exhibit in a place so integral to the history of punk — it fits.

It wasn’t on purpose [laughs] but the UK is such a mecca, and I think that’s what makes the London Deisgn Museum cool — is that it’s in this context, and not New Haven, Connecticut — it’s fucking London! I liked what you were saying about how skating is an act appropriation, that it’s about taking the things that are either are there but unavailable and saying, “Fuck that, I’ll use it how I like.” It’s totally dada! It’s like, “Here’s this bench, fuck that I’m not sitting on it! I’m doing a backsmith grind across this shit!” [Laughs]

There’s this intimacy you get with design. I can tell you the width and thickness of the handrail at City Hall in Philadelphia. I can tell you what the granite on the ledges of Love Park felt like. I can recall the color, texture, the height and the seam on the granite, the rhythm of the bricks under your feet, all that. You just register all this on a subconscious level before you even know what the word “design” is. I had no idea what architecture and design were when I was growing up. Nobody told me.

It’s a more intimate knowledge, actually being on the surface and trying to figure out how to maneuver it.

It’s so much more intimate because you’re on it. Especially for me, growing up in a city like Boston, you’re on it winter, spring, summer, fall. I know what the temperature of that ledge is in August vs. January. I don’t know that there’s another way to get to know architecture as well. It’s the things that humans touch — not the fiftieth floor, but the ground floor. I don’t think there’s a better way to study architecture than skating. It’s the art of crafting the human experience with space. All the best skate spots are the result of great spatial thought.

Lawrence Halprin, who designed Embarcadero, his wife Anna Halprin was a choreographer — she’s amazing. They talked about architecture as choreography, and they would do these choreographed schedules: 8am have your coffee and sit on the bench, 9am walk into the building, etc. They would choreograph their spaces. And I think he might’ve been fascinated with the way that Embarcadero became a hotbed for street skating in the 90s, and was really the petri dish where the culture grew. The architect of Love Park, the architect of Brooklyn Banks, these guys are part of that second wave modernism — they’re the people who would’ve studied under Louis Kahn– that’s the way that the plazas in streetskating were born. They kind of go hand in hand.

Which is interesting because not a lot of people consider skateboarding in relation to art, to architecture, to design — maybe not until very recently. Because, you know, there’s a history of delinquency being attached to skateboarding, which is true to an extent, but people don’t see the intention and the art behind it — that it’s more than going and trashing some place.

I think it’s hard for people from the outside who don’t understand — they just hear the noise and they see the damage. But they don’t realize the shelter that skateboarding has created for people, the inclusivity of skateboarding, the education that’s happening in skateboarding, the mentorship that’s happening in skateboarding — it’s a profoundly positive impact on society. When I grew up, the general public did not see that at all. Cops take your board and give you a ticket. At Prudential Center in Boston, there was someone up on the tenth floor who would pour water on us from above. One time a guy intentionally drove into a skateboarder, and then a bunch of skaters came out and smashed his windows with their boards. It can go the wrong way, but it really should be celebrated and embraced. And now it is in many cities — most cities have safe places to skate.

To that point, pretty recently in the history of skateboarding are we seeing a move from the fringe to the center — skateboarding is in the Olympics now, it’s getting legitimized in a way it hasn’t been before. What do you think of that?

What’s great is that skateboarding continues to have subcultures. So this move into mainstream — that’s a move for some people, but not for everyone. Skating moved into the mainstream in the late 80s and created a caricature of itself, a cliche of itself — we had Gleaming the Cube. But then it pulled back and skaters went underground again. There’s always gonna be a die-hard skater-for-skater culture and economy — and that’s where it touches so many more people. And that’s good too.

Which isn’t to say that cops aren’t still going to try and kick you out of places [laughs] But it’s a bit of a double edged sword, because yes you have more people getting invited to the sport, but then you give corporations more opportunities to captialize off of and exploit the culture.

Skating gets exploited a lot. It’s an 80 billion dollar global industry, so to become that size means there's a lot of exploitation of labor, of identity– there's a lot of theft going on. But in the end, what are the benefits? The more people skating means that more of the most talented people — who might’ve otherwise been cross country runners — discover skating and then push the limits of what skateboarding can do. That’s the number one benefit. The more people who skate, the more supertalents emerge, the more cultures adopt skateboarding.

I think of globalism as total bullshit — go to McDonalds in Paris and the waiters take themselves very seriously and you can get a burger on a baguette. Go to Milan and it takes them half an hour to get you a burger and it’s not even fast food anymore. Go to Antwerp and they have that whole initiative where McDonalds is all run by handicap people and it’s this real socially conscious place. And then hit the McDonalds drive through on the 101 freeway, and it’s a different thing all together. So, as cultures adopt skateboarding, you get a different take on it.

It’s been really fascinating to watch the explosion of skateboarders coming out of Japan, because the Japanese take what they do so seriously. The perfect example — I remember this science fiction novel by Peter Milligan — in one of his later books, his written in the oughts, his character muses over the fact that the Japanese will take scrambled eggs and bacon and they will make the most perfect eggs and bacon you have ever had. They’ll take the American bomber jacket and they’ll make it perfect. They’ll perfect things. And in George Nelson’s introduction to “How To Wrap Five Eggs,” which is an exhibition about premodern and indigenous Japanese packaging, he asks himself why the Japanese execute such quality packaging, and he just comes to the conclusion that they have to. It’s because they have to. So when you watch Japanese skaters who are so meticulous, so crafted, so focused, and so consistent — I really think it’s a reflection of that cultural attitude of "They have to be that way." So it’s a net positive. As we start to see more cultures adopt skateboarding, we’re going to start to see different takes on skateboardin. We’re gonna see it evolve in really interesting ways. That's the blessing. I really think the more people skate the better. It's a beautiful thing, it's a wonderful thing to do, it’s a positive thing to do.

And there’s no hierarchy — I can go to the spot and get my ass handed to me by a twelve year old.

It's changed a lot too. In the 90s in cities, skateboarding was definitely intimidating. You had to show up to the spot, and if you sucked, people would snake you and you’d get no respect. If you tried too hard you got no respect. If you had wack shorts you got no respect. It was really a stricter culture. And it was inclusive racially, but it was a time when hip hop culture was very homophobic, and it was a time when skate magazines were pretty misognnistic and homophobic. The culture has definitely opened up a lot. I think it’s also a generational shift. You’re starting to see more people skating, the changing of the guard of the editors at the magazines, and the companies really advocating for diversity in skating. It's been a really nice thing to see. And now you go to the spot and no one’s gonna kick your ass because you suck. No one’s gonna kick you out of the spot. That would be crazy.

If anything, if someone tries to kick someone else out, then everyone’s on their ass.

It’s unthinkable — the level of bullying that used to happen that was considered absolutely normal and part of the culture. It’s part of what made it so renegade. Obviously I don’t miss the discriminatory practices, but I do sometimes miss the edge. There was an edge to skating in the 90s — it was illegal, it was dirty.

And now you have videos of cops kick flipping and everyone being into it.

We would’ve dreamt for that in the 80s and 90s. But it’s all good. It’s an evolving thing.

And Converse has played a really cool part in that evolution. The first shoes I ever skated were these Converse that eventually became entirely smooth on the bottom. Out of all the footwear brands, how did you decide to work with Converse specifically on this?

Europe has different funding models for cultural initiatives. So in the US, you’re either gonna go for private or corporate funding. So it was very important to find a corporate sponsor that was organic — it had to be an organic fit. You wouldn’t go to Dick’s Sporting Goods. You wanna do it with a brand that has an organic presence in skateboarding, that is making a contribution to skateboarding, and is respected by skateboarders and the industry. Going back to that idea theft and taking advantage of things– it’s great when you see a company that really gives back.

And look at their team — no one else has a team like that.

They have a good team, they’ve had a good team, and they treat their riders well. They were patrons of this exhibition, and the intent of this exhibition was really to be a gift to skateboarding and a gift to design, and to make them realize that they’re not so far from eachother. And Converse made that happen.

What’s the best trick you’ve ever landed?

I don’t want to embarrass myself. Let’s just say I’m not on the Converse team for a reason. What about you?

Nollie half cab switch grind. I got it at the Berrics too. It was really cool. I got it fast and clean. I’ve never felt better than when I was riding away. That’s a trick I’ve wanted since I was 13 and I got it at 38. I learned smith grinds at 36 and I’d always wanted them, and it wasn’t until someone told me that a smith grind is a lazy 50-50, then I got it. One of my favorite tricks.

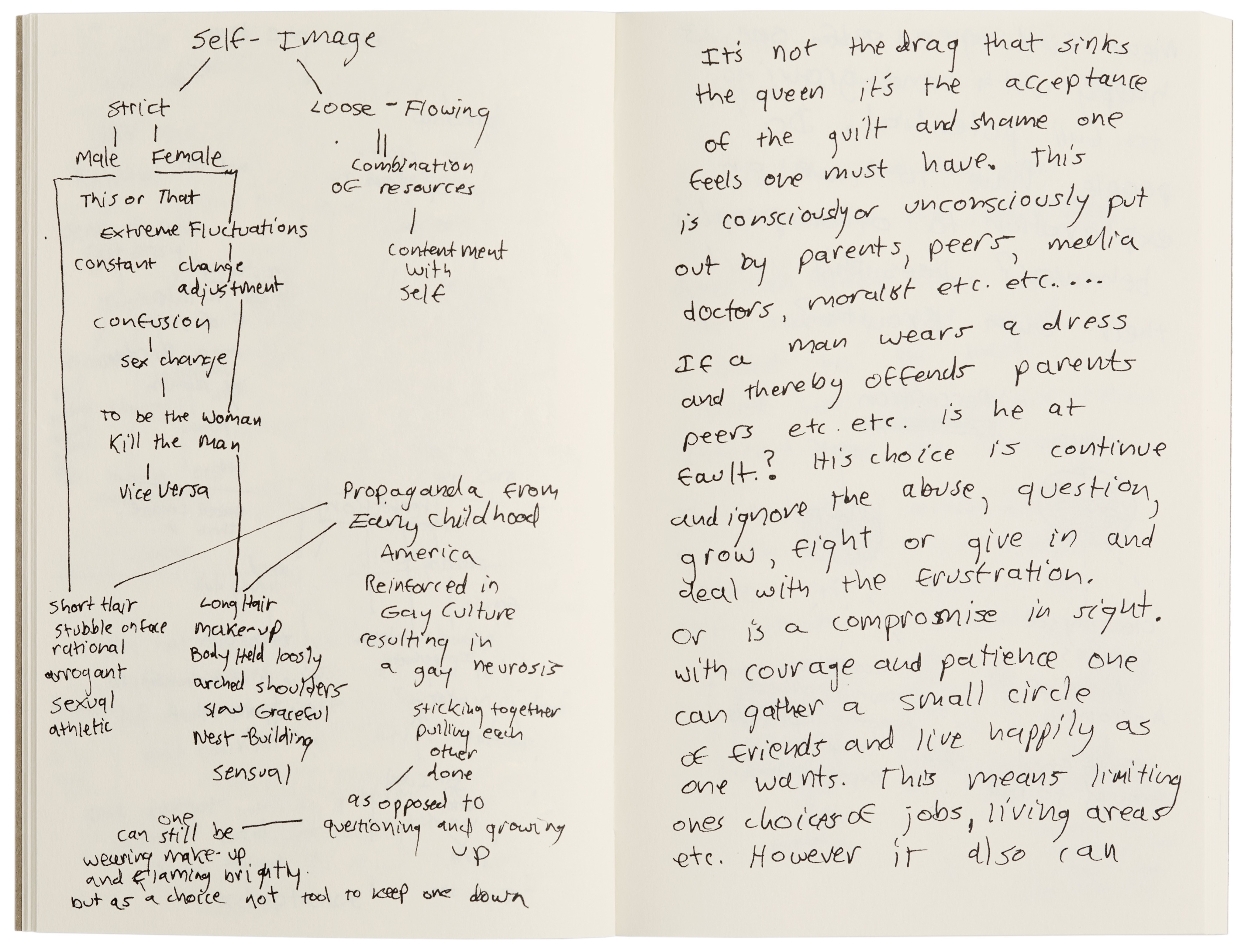

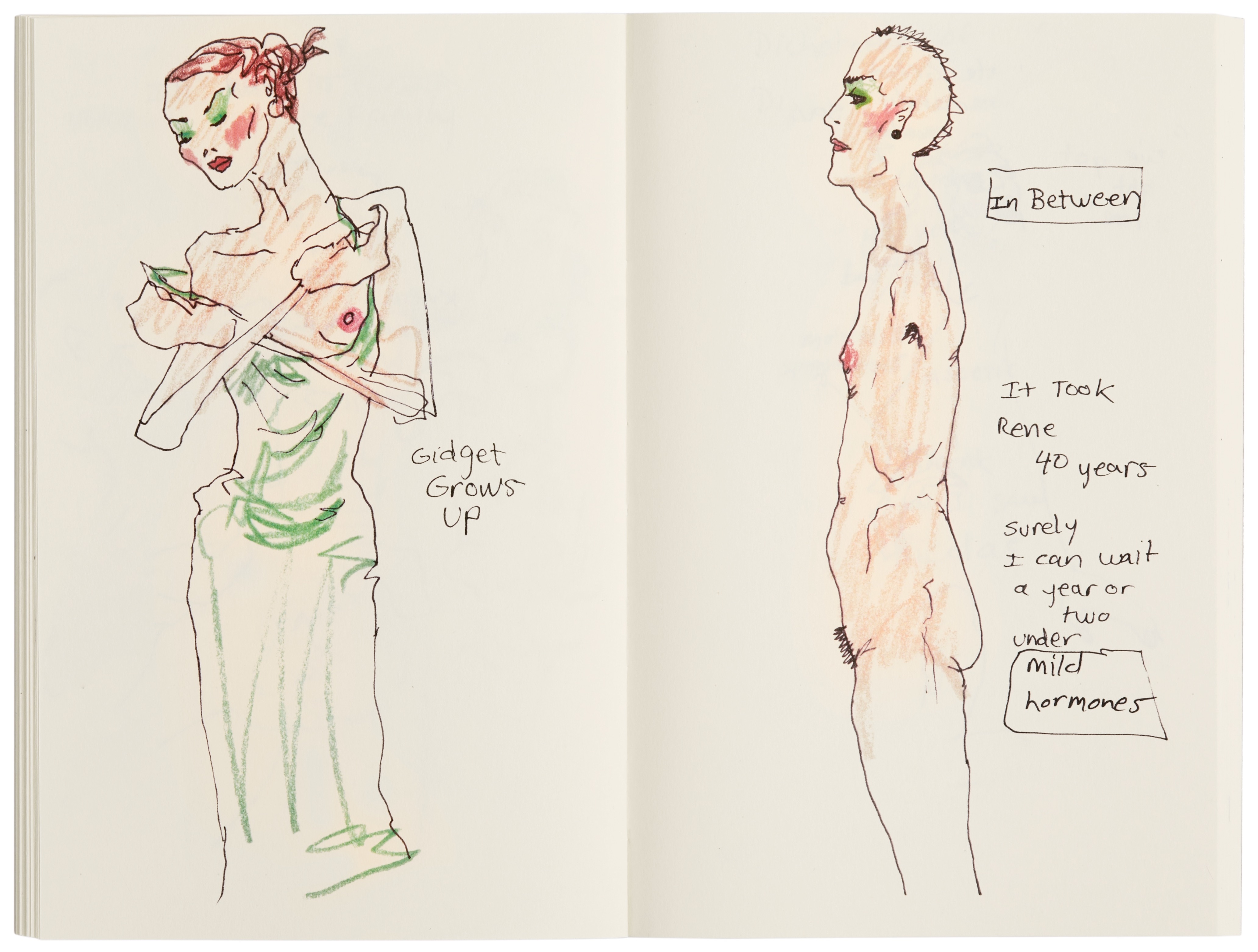

“If you think you have the wrong body, you are always going to think about it,” nineteen year old Greer Lankton pens in her Sketchbook, September 1977. A running theme throughout, we see it questioned and translated through an arrangement of sketches, diagrams, and scattered but mindful musings of a young girl attempting to reconcile with herself. She dives headfirst into deep contemplation of gender, her surroundings, and her inner world. The pages span over two years, beginning just prior to her move to the capital city and leading up to her sex change. In the early stages, she frantically contemplates her body’s inner workings, chronicling her consumption and her battle with asthma in a diary-like fashion. As the journal progresses, it transforms into a collection of etched portraits and depictions of skeletal figures, exploring the possibilities of a social and medical transition.

I initially read Sketchbook, September 1977 in an afternoon or so, unable to look away. Lankton was around the same age as I was when I became distinctly aware of the dissonance between my mind and body, which ultimately led to not only a gendered transition, but an entire shift in my world view once I moved to New York. I felt a tender sense of empathy as she approached the threshold from teenhood to womanhood, a time of whimsy and transformative curiosity. Her youthful longing for clarity resonated with me. Living in a vessel, or “vehicle” as she calls it, lacking a manual is a universal human experience. Yet, reconciling your body and mind as a transexual can be isolating. There were moments when reading her inner dialogue from an era before I was born, rife with heartfelt questions and commentary straight from the privacy of her pen, that left me breathless. How could someone who lived decades ago feel so close? How did she tap into my thoughts?

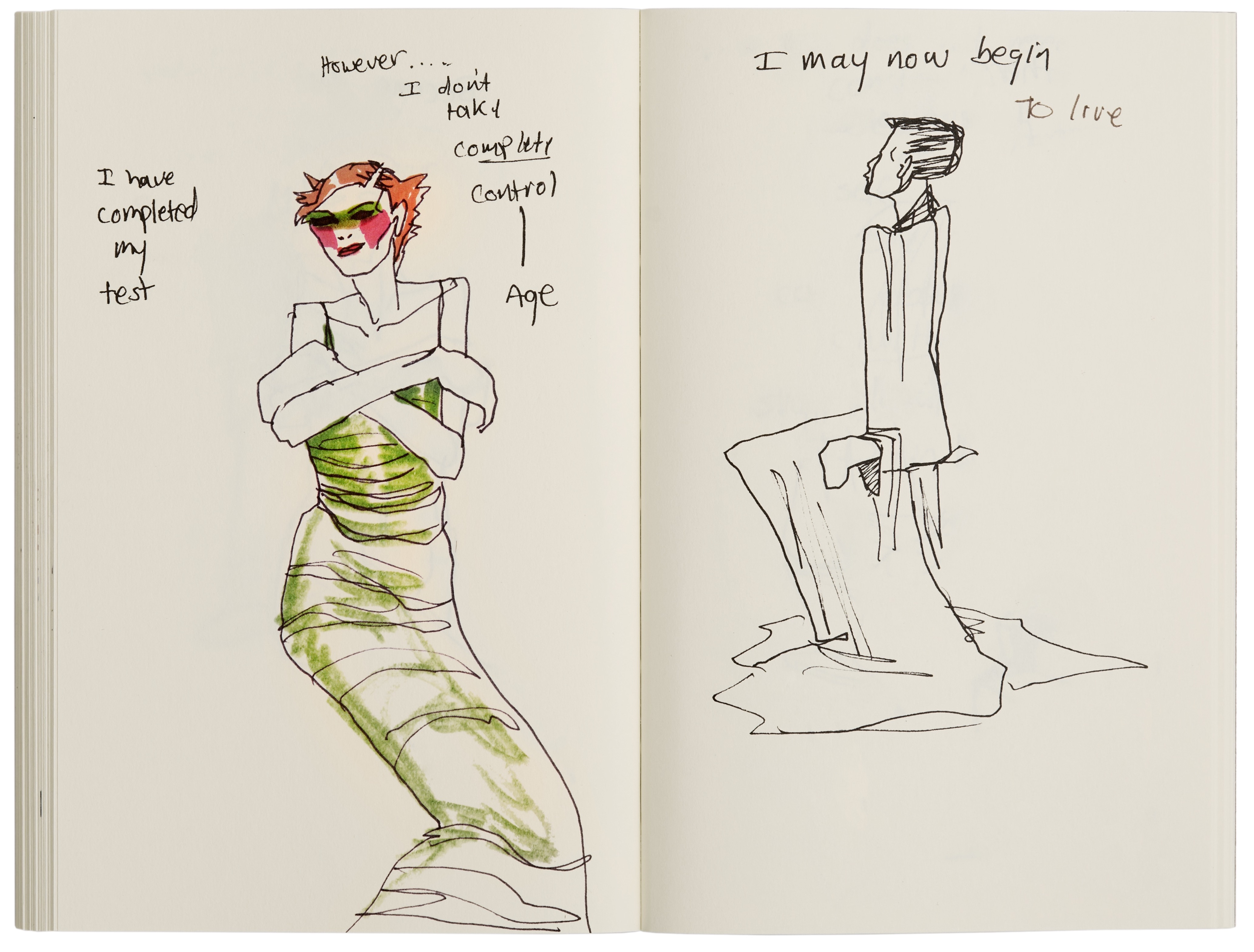

Many of Lankton's questions can be seen as an expression of her desire for self-preservation, often followed by affirmative sentiments as if she is reassuring herself that it's alright to continue, to survive. She pleads with herself to believe, 'It couldn't be worse than it was... It's worth it.' While contemplating the polarizing commentary and criticism surrounding her life and work, I found this early journal to be a testament to the author's character from a young age. Her pursuit of growth in the name of survival tells the story of a tragically hopeful girl.

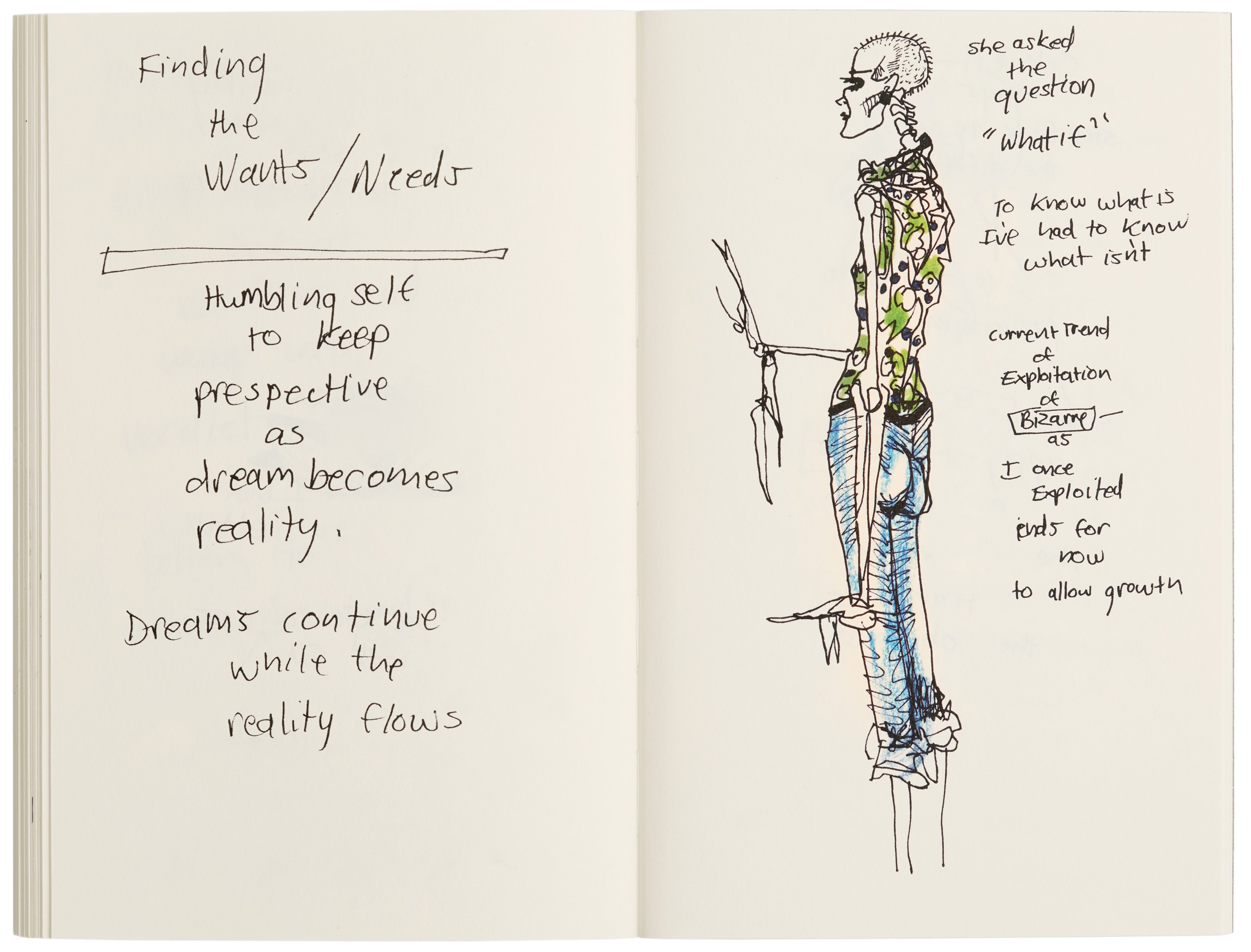

Dealing with the unknowns of transitioning, the artist engages in pointed conversation with herself about the proposed material reality intertwined with her gender. Romance, public perception, her relationships and her duties to her body at the cost of becoming… were suddenly tentative to change. Fear of failure and rejection would naturally set in for anyone, and it does. In defiance, she reminds herself gently, “The truth is, I’m alright… there’s nothing to prove.” The latter half of the journal is mostly sketches, exhibiting a medically informed knowledge of the bodily form, nodding to her obsession with the skeleton as we see in the stories she would come to tell in her renowned craft. Lankton seems to showcase depictions of herself in and around many of the drawings, expressive in her continued grappling with what it will take to answer the question of her transsexuality. Nearing the final pages, she states that she will be “free to continue,” and that she has.

This sketchbook provides a prologue to the Greer Lankton the world would come to know. Her legacy has long outlived her in many of her sketches that would later become life-size dolls, inspiring installations filling entire rooms. As I read September 1977, I felt guided by her voice narrating a journey from the metaphysical world into her body, overlooking what would become her actualized form and eventually her life’s work. The detailed insight to the artist’s mind gives way to a sociological and painfully human approach to understanding oneself. “Now that I have a glimpse of self I have caught the glimmer outside of my own body,” she wrote. As her life and career blossomed into a staple presence in the art world of the 80s, we would see many of the fruits of her emotional labor she documented fervently in 1977. This was Greer as she was before her stories were told by others, a girl with the will to transform. I heard her piercing voice as she immortalized herself on the pages, speculation and hearsay falling aside. This was her story.

I’ve said often that transness is a testament to intuition. Led by a profound understanding that our bodies are malleable in nature, we claim agency by assuming the task of evolution. When hearing of Greer Lankton and her work, I was intrigued by the archival documentation of seemingly autobiographical experiences through the crafting of hand-sewn dolls. I saw much of myself in many of them, now with a greater insight into the inspirations of their creator herself. There was an acceptance of her own evolution of body and mind, even if never finished nor always at the same pace. “I will not die, I will become.”

Following the loss of nearly a generation of queer and trans elders in the 80s and 90s, holding her diary feels like an anchor to her humanity, no matter the distance between us. I grew up feeling like the only girl in the world, isolated by my emotions, a belief that was shattered when I met The Dolls. My trans mother once said to me, “You’re not going through anything no one hasn’t gone through before” and it has been a great comfort to me since. Reading Sketchbook, September 1977 reminded me of the same when Lankton wrote above an outline of what seems to be a version of her own face, “I may now begin to live as others have before.”

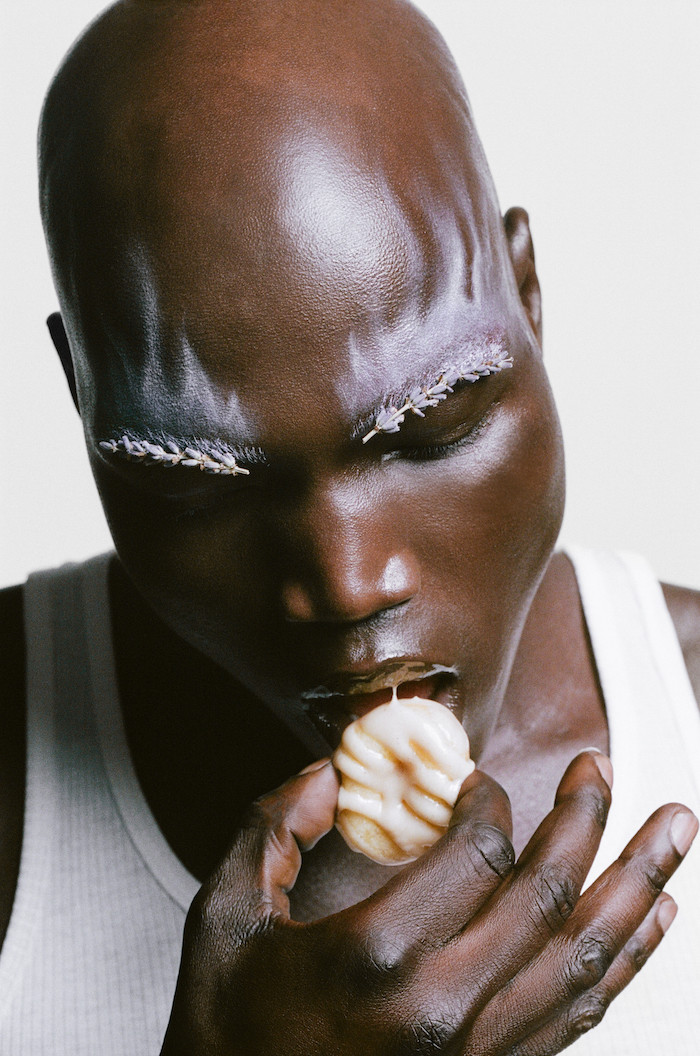

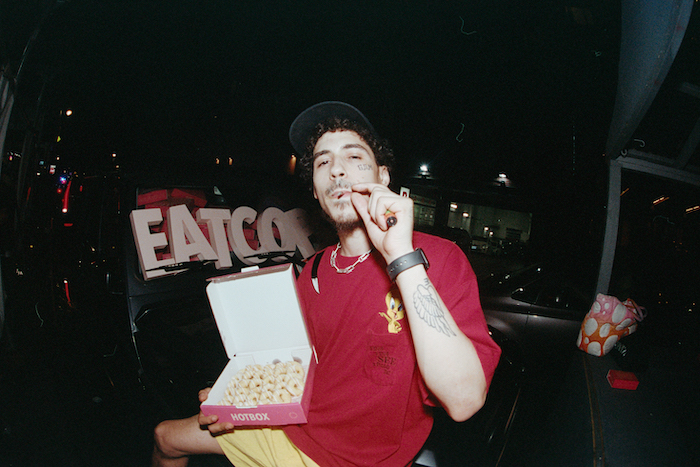

“We believe we're destined to inspire the world around us. We want anyone in fashion, design, or art to look at what we're doing on a creative level and be inspired,” White continues. Aside from purveying delectable mini donuts, which come in two classic cinnamon sugar and sour cream flavors, COPS also champions local creatives within all different scenes — from working with NYC-based spatial designer Christine Espinal on a one-of-ak-kind event installation to Toronto-based designer Spencer Badu for an exclusive uniform collab.

Acting as an artistic outlet for the COPS team, they also introduce one custom weekly flavor, orchestrated in partnership with a food scientist and fine dining chef. “We also worked with another fine-dining chef last year; his name is Brandon Olsen. He curated a bunch of our weekly feature glazes, so the plan is to work with multiple chefs from around the world on different glazes, showcasing their capabilities and their own flavor profiles,” White expands.

Whether they are hotboxing a G Wagon outside of Soho House or curating event installations around the world, COPS is sure to bring the heat no matter what boundary they decide to push next. “Anything can be art if it's placed in the right setting or in the right context — and if the storytelling is right. It's just a matter of romanticizing it. We ultimately want to curate this awesome community of creative connection,” White concludes.