Natalya Nesterova Back at Hal Bromm, 35 Years Later

At a glance, many of Nesterova’s paintings depict a sort of peaceful mundanity, her subjects shown attending the circus, reading novels, and frolicking through forests and on beaches in a folk-adjacent, somewhat primitivist style. Perhaps it’s the cursory impression of idyll this subject matter leaves the viewer with that allowed Nesterova to not only elude political persecution for much of her life but to achieve acclaim both within and outside of the USSR in a manner similar to that of composer Dmitri Shostakovich. Having received many awards and titles in Russia, Nesterova was considered a valuable cultural export, her work then being featured in over sixty exhibitions throughout the United States and Europe. Fearing retaliation for her outspoken stance opposing war in Ukraine, she did eventually leave Russia in March 2022 and passed away shortly after in August.

Though Nesterova was understandably reticent when it came to making definitive claims about the meaning of her art, once saying that her work is simply “about what you see,” her paintings belie themes of interpersonal and environmental alienation in both their content and form quite clearly. Or at least—that’s what I “see” in them, and is what I expect will resonate acutely with present-day New Yorkers when her first posthumous exhibition opens on April 20 at Hal Bromm Gallery (the site of her first-ever American exhibition in 1988). View some of her pieces below and consider Nesterova might have been aiming to convey beyond the surface.

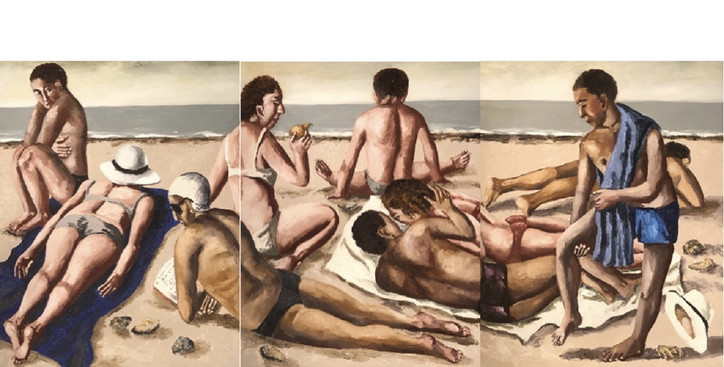

This triptych depicting a seemingly ordinary day at the beach makes use of a slight misalignment of the three individual paintings within it, one of Nesterova’s stylistic motifs. Though subtle and plausibly unintentional, the motif of slightly misaligned diptychs and triptychs is consistent with the vaguely unsettling flavor of Nesterova’s paintings and enriches its thematic potential as it renders those depicted along the seams quite literally disconnected from themselves.

This choice emerges as a more clearly intentional one as you consider that not one of the nine people in the triptych is facing either us nor each other fully head-on—not even the only two people who appear to be visiting the beach together. This couple, the only pair in the painting sharing a towel and making physical contact, is ignored by most of the other beachgoers and given suspicious sidelong glances by another man and woman (who themselves are separated by a facedown sunbather between them). The woman looks down her nose at the couple—or maybe just at the pear she is about to consume. Just another day at the sunless, grey-watered beach of Nesterova’s creation.

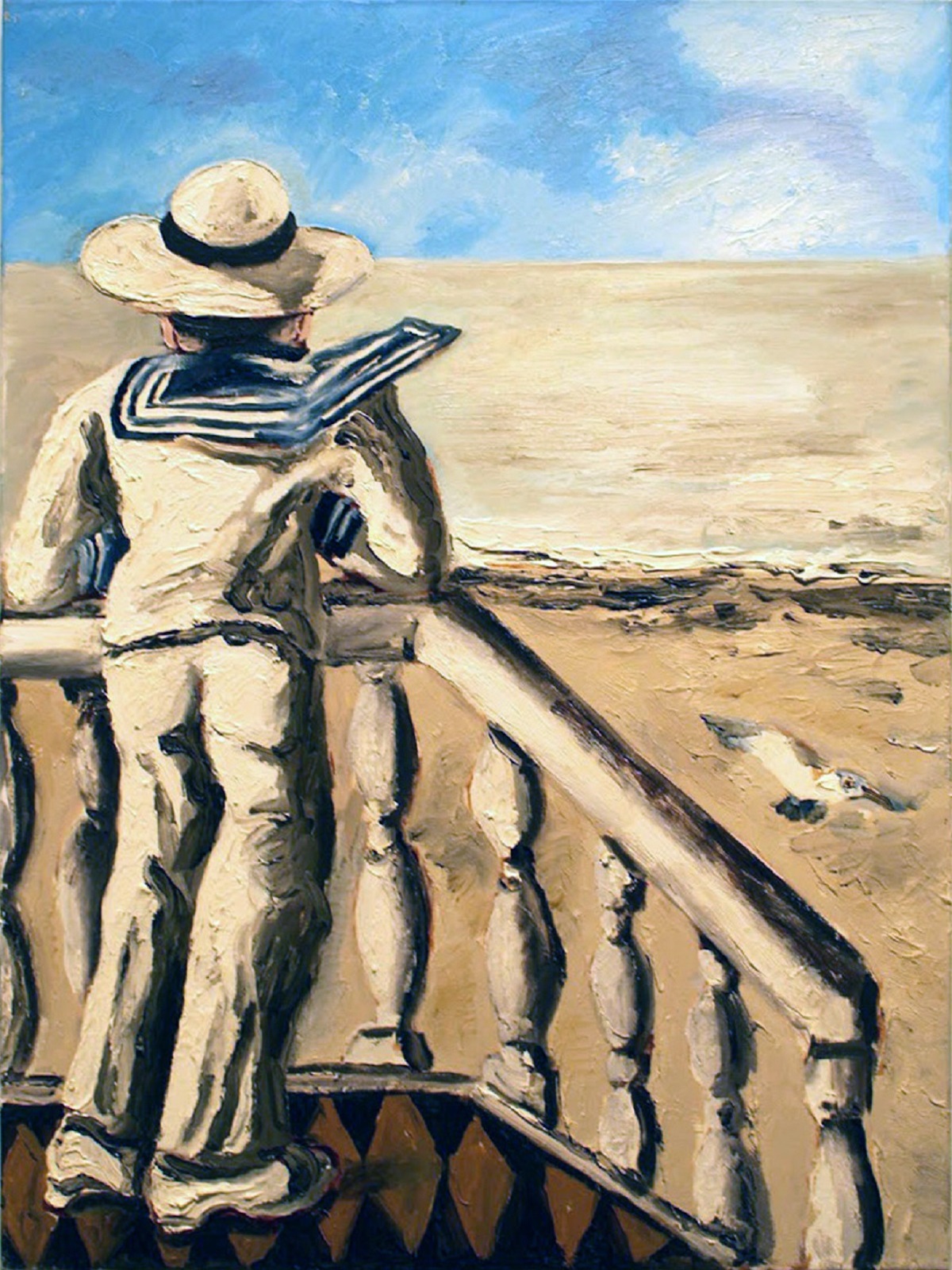

Nesterova narrows focus on a pair of beachgoers in her breeze paintings, one man and one woman. We can only see them from behind as they stare out onto the horizon, both off-center and seemingly occupying opposite sides of the same viewing deck--though the sky that the man looks out at is much brighter and clearer. It’s not clear who or what is between them, if anything.

This polyptych depiction of a circus, immediately aggravating to the eye with its juxtaposition of opposing blue and gold tones, makes use of misalignment along the seams of the individual paintings similar to that of the beach triptych. In spite of the horses being our focal point, very few of the circus attendees within the painting are looking directly at the show, preferring instead to look at each other, the jesters in the aisles, or seemingly nothing in particular and again preventing the viewer from seeing any of their faces from a fully frontal angle. The horses’ subjugation at the hands of the circus ringleaders is emphasized by their fragmentation along the lines of both the polyptych and their bisection by the festive garb they are adorned with.

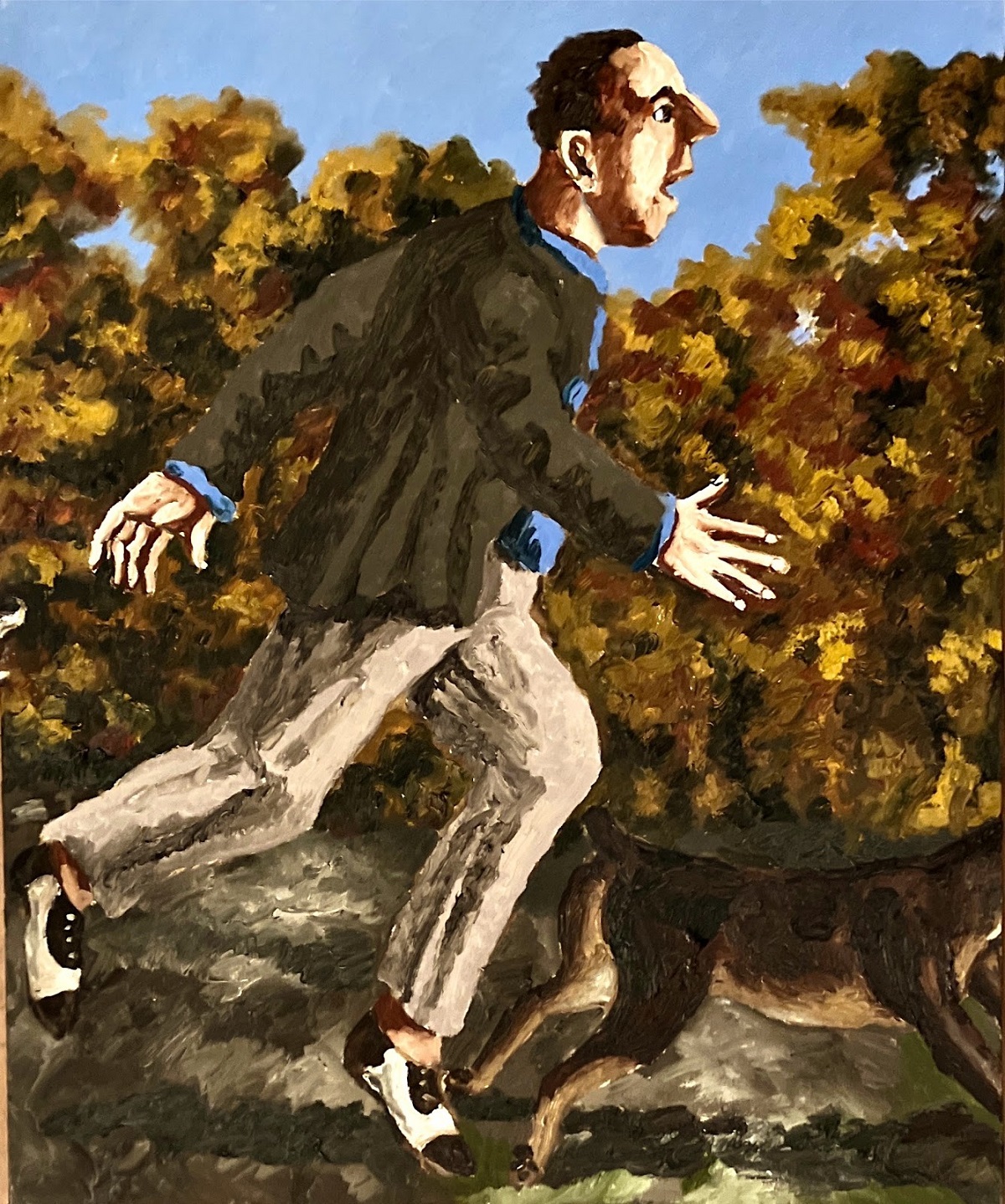

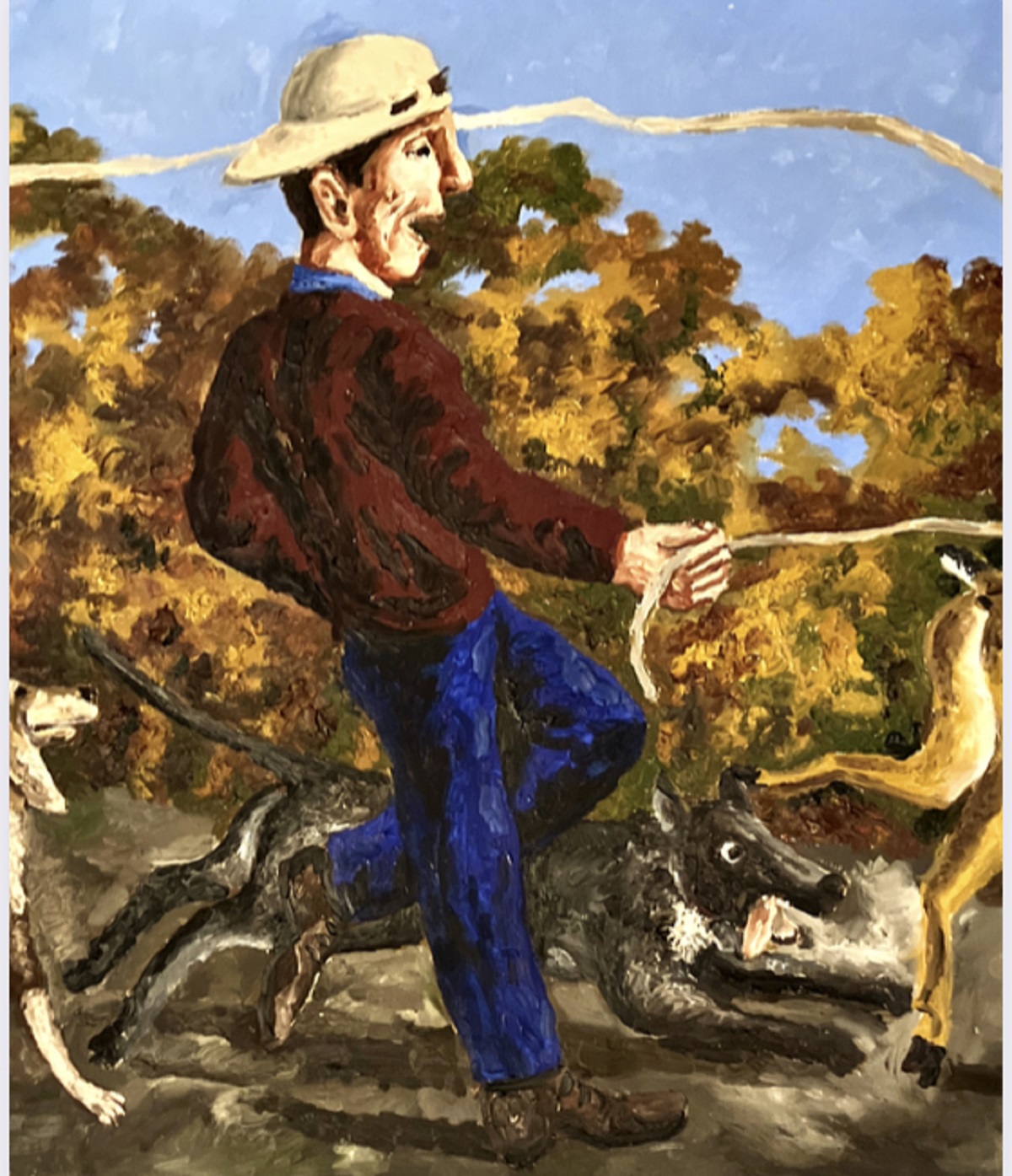

The dogs of Nesterova’s hunting series suffer a similar fate, fragmented into limbs from the viewer’s perspective by human legs and the limits of the canvas. The human hunters are visible only from the side, all striving towards something just out of our view.

The composition of the hunting series presents an intriguing parallel with Entreaty, in which a humanoid figure is depicted in full profile, similarly looking and reaching toward something we cannot see. The cool tones stand out in comparison to Nesterova’s usual color palette, and the depiction of this figure as both all-white and dappled with eyes suggests that the ability to truly see comes with a cleansing of the self from the usual trappings of public life. Whereas the human hunters are always in a position above the dogs they employ in the hunt, the figure in Entreaty has sunk to the grassy floor, pursuing something not in front of nor beneath but above themselves.

Nesterova’s work strikes the kind of delicate balance between the real and surreal which can evoke a feeling that something is not quite right even before one has the chance to figure out why. Her ability to subtly convey discontentment with the state of public life and our isolation from the natural world in a manner relevant to audiences across decades and nations is a powerful one. It’s the kind of power that makes it difficult to be forgotten; Nesterova has already stirred controversy in death when a museumgoer complained in February 2023 that they could not identify Judas in her depiction of The Last Supper, leading to the removal of longtime museum director Zelfira Tregulova from her position. It is also the kind of power that makes it worth it to see her paintings while you can, and to consider what circuses we ignore and entreaties we make in the context of our own lives and milieu.

Natalya Nesterova: Counterpoint opens at Hal Bromm Gallery on April 20 and is on view until June 28, 2023.