New Breed

We first met Dawn Richard as a wide-eyed girl on MTV's Making the Band 3, entertainment behemoth P. Diddy's 2004 reality competition that set out to turn five unknown girls into the next big international girl group. The result, as you probably know: Danity Kane, the widely popular group whose name actually comes from an anime character that Dawn created. On the show, she stood out—arguably as Diddy's favorite—and after the group broke up he recruited her to be in Diddy - Dirty Money, a collaborative project that quickly ran its course. She describes to me in great detail the horrors of Diddy’s reign over her entire career, and it’s not pretty.

It may sound like a cliche to describe Dawn’s new record, new breed, as freeing, but it fully is. After contemplating whether or not she should still do music (she has done everything completely independently after being dropped by Diddy), she visited her hometown of New Orleans for the first time since being displaced by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. The richness of this culture and her own familial connection to the Washitaw Indians who reside in the city were enough of a catalyst to inspire a dynamic, funky and often experimental body of work.

And just as Dawn herself has always transcended the stereotypes and expectations thrust upon her by other people, new breed does the same—a long overdue homage to her people that proves her prowess as an R&B chameleon.

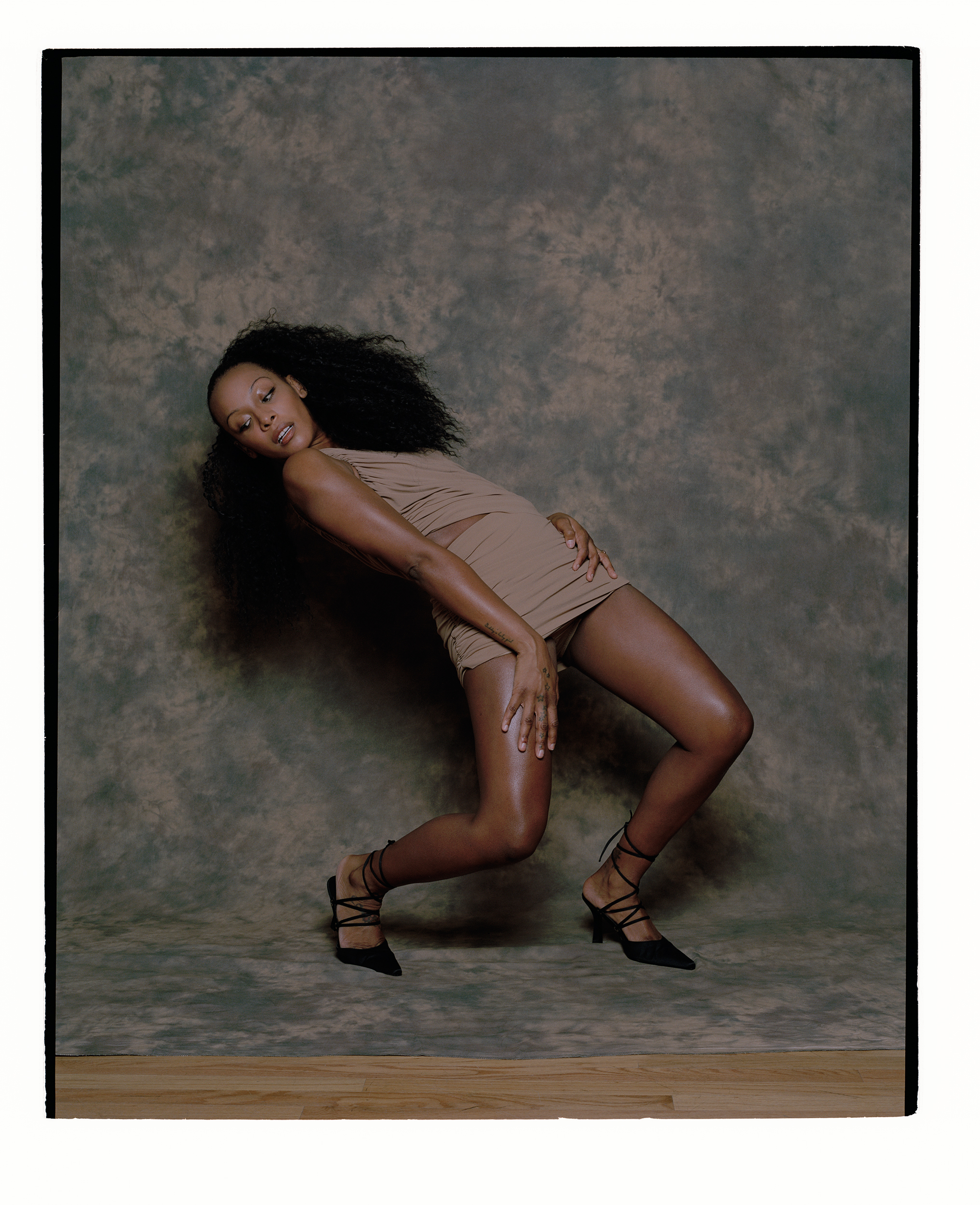

Ruched top and skirt by Norma Kamali, shoes are stylist's own.

You were talking about LA and locations. When did you start living in LA permanently?

The day I moved to LA was the day after I left Puff’s office and asked if he would take me as a solo artist. And when he said that he wouldn’t, I left New York and went to LA because we had just finished recording the album. And I stayed, and never went back.

I know you were displaced by Hurricane Katrina. You’ve been in all these difference cities and locations. How do you think where you’re located has played a role in your art?

Location does affect music for me. I guess I was just spoiled. I didn’t realize how spoiled I was in New Orleans until I left. I didn’t realize how special it was until I didn’t have it anymore, and I realized that there were just certain things that I didn’t have access to anymore. And New Orleans was very much that for me. I’ve lived in a lot of different places. I love New York, and I think there are great things about LA. But there is just nothing like the people in New Orleans, and I missed that camaraderie, that neighborhood, that place where everyone raised you and everyone knows you. If you say somebody’s last name in New Orleans, they probably know your whole damn family.

I miss that. Because every other place is just so big. LA is so massive, and New York is this grandiose idea. New Orleans is a small city, and even though it’s a city, it’s very much like a town. I do believe that location matters, and New Orleans, for me, was safety.

A small town girl. I’m from the South too, so I definitely know what that’s like. Did you write most of the album in LA?

In New Orleans. I went home. I didn’t think I was gonna do more music. I did my [album] trilogy—we did thirty visuals with no budget and no label, and I was exhausted. I felt like I had did all that and I didn’t really go anywhere; like I was pushing and pushing, and it really wasn’t getting me anywhere. I was like, ‘Okay, I’m proud of what I put out, but maybe I should take a break.’ I had been animating with Adult Swim. It was a good job, and I was like, ‘Maybe this is it.’ Then I went home and I realized that I had missed everything. I was 18 when Katrina happened, and then Danity Kane happened. So, I never got an opportunity as a young adult to put New Orleans into my music—to really take my city and go and do great things. For example, Chance the Rapper with Chicago; Big Freedia, how she was able to take New Orleans; Beyonce and Houston, Texas; Janelle Monae and Atlanta—I never had that opportunity. So, when I went home, all those things started coming back—working in those different studios and seeing all my musicians and friends—and I realized I had never told that story. It was gone before I could even tell it. Usually people early on in their career have the opportunity to really encompass that, but I was homeless. I had no connections. I couldn’t get Trombone Shorty and all those people who had been with my father, and all those Mardi Gras Indians—I couldn’t get those people because they were gone.

But I went home and all those people were back. So, I started to walk the streets and write and record, and I realized that I’m not done yet. I have a story to tell, and I finally get to tell it. I finally get to show people who I was long before Danity Kane. Before Making the Band, I was an artist. Before Making the Band, I was already in a culture that was so thick and rich, and I would’ve put that into my earlier music had I been able to do it. But we didn’t have a home to do that with. So, I just got reacquainted. One song turned into three, three songs turned into five. And then I went and talked to my uncle’s tribe, the Washitaw Indians and I asked for permission to tell our story. I wasn’t gonna do it if I didn’t get permission from the tribe. And I decided to go on this path, and that’s how this album came about.

How was it different going back to New Orleans? Both mentally and even physically being there.

It’s not the same, but it is in a way. It still smells the same. The accent is still the same, the food still tastes the same. But you can see that it’s gentrified, you know? It’s not the old New Orleans I know, but any piece of New Orleans is enough. Any slice of it is better than no slice at all. And it’s what I know. My father is rooted in it, my grandfather played with Fats Domino, my great uncle is in the Hall of Fame for sewing all the Mardi Gras costumes. So, it’s all I know. And I love it when I walk the streets. They know my dad, they respect my father. On the album, a lot of the interludes are my father’s own music. His band was really popular in the city, and it just feels good. I don’t think people realize how much I didn’t get a chance to have that. It was stripped from us. But as an adult going back, I realized how much it did affect us and dictate the rest of my life. I wanted to pay homage to that.

That’s interesting. Life happened, things happened, and you just somehow never got a chance to tell that story.

Not even tell that story, but embody it, you know? It’s so rich within my family, and it was so much of who we were. Every part of my family is from New Orleans, so we all lost everything. That level of how rooted I was in the city, I didn’t realized it ‘til I was gone. So, if anything, I just wanna give something back and just give y’all some honest, raw ass shit. Before all the crazy, this was who I am at my core.

It happened right at the time that you entered Making the Band, and I was thinking about how Making the Band was a part of this sort of ‘formative culture’ in the early 2000s. We loved to watch people on reality competitions like American Idol and build them up from a no one to a someone. You were shaped by all these different people—Diddy, your fans.

Yeah, and they told us who we were supposed to be. They gave us our title, which, some of that story is true. But it gets interesting because then that becomes your only story—people only see you as that. And though they saw me go through Katrina, they only saw me as one thing. But I was something else, as well—we all were. And I think women oftentimes are told their own stories: you’re a woman, you’re from this, you’re black, you’re white, you should be this.

I saw Diddy was featured on the Blood Orange album, which shows he’s kinda dipping into this more 'indie' realm. Would you ever work with Puff again?

I love Puff. Puff is a genius. He’s got one of the most incredible ears. It’s Puff. It’s respect. But it would be on my terms, always, which is something we never really had before. I think I earned that right.

The production on this new album is insane. What were your influences? What current artists are you obsessed with that might have influenced this album?

I produced most of it myself—this is the first album that I’ve produced this much. I’m very proud of myself because I was worried to take that on, but I had been building to that for quite some time, and if it was gonna be New Orleans—if it was gonna be me—I wanted it to be all me. So yeah, I’m glad you like it. I’m really proud of this album, and I’m really glad you like it because it’s a risk. It’s very different from what I was doing previously, and I hope people can really see the depth and the versatility.

Were there any obscure references that inspired the album? Or any pop culture imagery or specific art?

A lot of it was taken from the Washitaw Indians. Chief Montana—kudos to him. He hand sewed everything on the headpieces we used. We have a docu-series that we’re going to put out with the album as well, because I want people to understand the culture. There is a respect to the Native American culture—why black indians started in the first place. It’s not some random thing we’re grabbing from the sky—it’s something that exists in our culture. And though in American culture it’s not looked at as a ‘real thing,’ we still as a culture grow up in that. It’s something that’s real to us as a city. It’s been going on for generations upon generations, and it is a respect to the Choctaw indians that were there before us, how we integrated with them and why we became the black indians, and the slaves that came… we mixed and caused a culture.

And if you know New Orleans and how mixed we were, we took all those spiritual and ancestral ceremonies and we kept them. They were sacred to us, and we passed them down. They saved lives and communities. Whether you hear it in the chanting [on the album], or in the stacking of the vocals, or in the talk between the women—especially in the beginning of “Jealousy,” the woman saying, “I’m on fire.” This level of respect to queens and how women are coming to the forefront—it is a huge cry to show that there is a new form of woman, a new breed coming up that is unapologetic about who they are. I really speak to that because growing up in a racial city—even though New Orleans is black, Louisiana is a predominantly Republican, white state. There is a Robert E. Lee statue that still sits around us, and even in the “New Breed” video, I purposely had that we take it down and we put a native person in place of it. There is a blatant cry in this album for people to see that we are proud of what we are, and our culture and our heritage we grew up in. That influence has definitely poured throughout the album.

You do anime with Adult Swim, and the name for Danity Kane actually came from one of your anime characters. Do you think growing up in that atmosphere kind of made you diverse and off-kilter in your interests, or is that just you?

That’s just me. It’s not about ‘being different’—it’s just who I am. It’s always been who I was. Now that time has passed, more and more people are starting to see, you know, maybe she wasn’t different, maybe this really is who she is. So many other black and people of color are coming out as coders, animators, comic book readers; you’ve got artists like Kelela, SZA, Blood Orange, Solange. When I was doing it in Danity Kane, people couldn’t detach it and see that that was me, too. But now as I’ve grown, I’ve realized that people just hadn’t seen it. It exists, but they weren’t given it at all in mainstream culture. But now the mainstream is starting to accept the ‘indie’ kid, so now people are realizing that maybe I’m not so different.

I’ve always been this girl, I will die this girl, and I’m proud of who I am. I’m proud that I stood out in a time when maybe it wasn’t popular. Janelle [Monae] did, too, and now she’s nominated for album of the year. Good for her. She kept that voice for the queer culture and for what she was for that culture. I’m just speaking the voice of what I am and what I represent. I’ve always loved tech, I’ve always loved animation, and most of the time I am the only black girl in those meetings. But that doesn’t mean that that can’t change, and that’s what I wanna advocate for. That’s why I work with Adult Swim as an animator. I don’t know if anyone else will choose that route, but I want people to know that you can do it all.

Tell me about the tour with Kimbra, and the tour with Danity Kane.

I’m just so proud of us. Again, we’re in a time when women are standing up in so many ways. I’m proud of us for having the talk, for having the ability to say that we don’t always agree on everything but understanding that we can still be a cohesive entity and we can still do something really great without being on the same page all the time. Women don’t always have to agree for them to still be sisters. I’m proud of what we accomplished and how we forgave each other, how we’re learning to maneuver and work with each other. This tour has been really great, and it’s genuine. It’s genuine in the fact that we’re still trying to figure out what it is. We know we love it, and each show it gets better. Each show we try something new, and we know that the commonality is you guys—the people who are rooting for us. The tours have been mostly sold out, and the ones that have been cancelled we’re trying to re-do. We’re not making any promises, but we like where we are so we’re looking at doing some recording and seeing where that goes, too.

As far as the Kimbra tour, again, I love that I can be both. I refuse for anyone to ever tell me that an artist can’t be all of it. I’m sorry, you can. And I think I’ve proven that with my catalogue. I’m proud that I’m able to go do a DK tour and rock with my gays, and we have the most incredible time at the House of Blues—full on Vegas shows—and then I go break it down to a bass, organ and piano and do a jazz arrangement with Kimbra, and do a tour in a contemporary arts museum, or in a chapel, or a synagogue. I love that I can do both and hold it.

It must be so fulfilling.

It has been so artistically fulfilling for me. And also as a dancer with DK, it fulfills the pop girl in me, which was very much present when I stood in that line when I was a kid. I am that girl, too. I’m very grateful that the fans are able to go to both types of things, and we see them learning themselves, right?

I would go to both of those shows.

It’s interesting because most of the fans that went to the DK stuff found themselves at the Kimbra show, even though they didn’t know who she really was, and they were blown away because they just saw a different version of something. It feels new to them, and I love that I can create that. I just want to be able to be the artist that I’d be proud of. I’m not trying to do it all. I just know that I do what I love and if it happens to be all, then I’ll take it. Nobody tells Childish Gambino not to be two different artists as a man. Why can’t we do the same? Why can he have two different names and do all that, and we applaud him, yet I do two different genres and that can’t work? It can.

Like The Rock being a wrestler and then becoming the biggest actor in the world.

Yeah, why can’t we be it all, too? Why do we have to be limited? Why do we do that to women?

Do you and DK perform together at your new show?

We do an intertwined show, so we do our solo works and we also do our DK stuff. I knew that I would only do it if we did it that way because I want each girl to feel like they can shine. That was the problem—we were told that it had to be either this or that. But like, no, you can be a superstar by your damn self, too. There was this level of, ‘Oh well your star can’t shine brighter than hers,’ but it’s like, no bitch, shine! That’s the problem with women—we’re so afraid and so competitive. But no, you can shine, I can shine and we can shine together. I think it’s been a great show for that.

I almost want to look back on Making the Band as, like, a cultural study.

Oh my God, it was rats in a maze. And we learned a lot, but it also showed the level of how you can take women and manipulate them and divide and conquer them, right? Then make them fight each other. There were a lot of things in that that were interesting. But I do think that we are learning, and I’m proud of us as women, to see the facade and see the illusion and see the game, and we’re changing the script. We’re banding together, and the more we do that, we’re going to see a shift in this industry. I just can’t fathom why we don’t have more women in power in the music industry. We need more executives, we need more women CEOs, because I think when we start seeing that, we’ll see a change in the way we see girl groups and female artists and how they look, how they’re portrayed, and how they are maneuvered. Because if we can have an artist who has two identities and can be an actor and a writer, then we can have women do the same.

You’re a totally independent artist.

Yeah, I’m like the definition of DIY.

What do you think it is that keeps you coming back and wanting to do it all by yourself as an independent artist?

I love this shit, man. I do. I love it, but it doesn’t define me—I choose to do this. I have a degree in marketing, a minor in marine science—I could go and open up an animation firm, you know? But I love this. And what I do realize is that it is hard work, but my journey can’t be for nothing. The things I have endured, the things I’ve gone through—if I can’t give something back so that it’s not as crazy for the next person, then shame on me. So, I’ll be this little indie king. I’ll do that, and I’ll hopefully inspire one girl to not have to endure the crazy shit I had to deal with, from the disrespect, to the bosses, to the homelessness; being called bitch, being called ugly, you name it. If I could help one person, then that’s what’s up.

‘new breed’ is out now.

Photo Assistant: Natalia Placios, Styling Assistant: Blair Cannon; Lead photo: Artifact embroidered dress by Vasilis.