No Such Thing as Pornography

Tell me about the project.

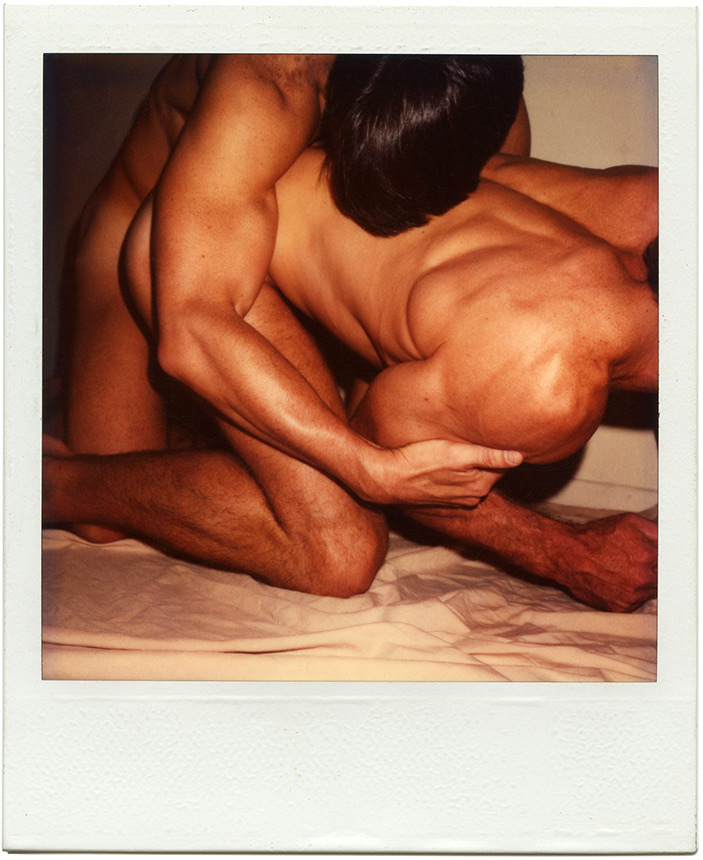

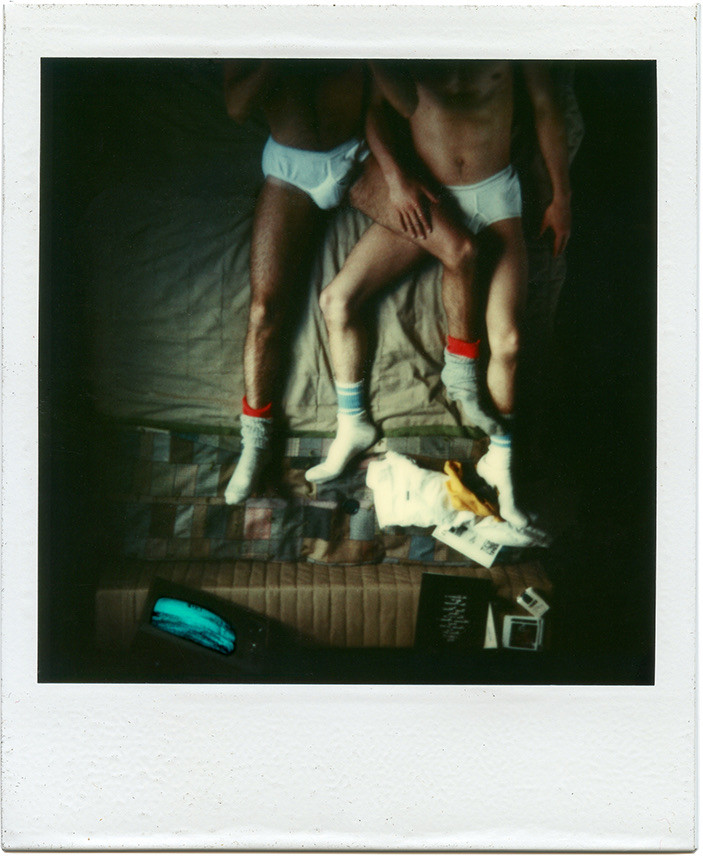

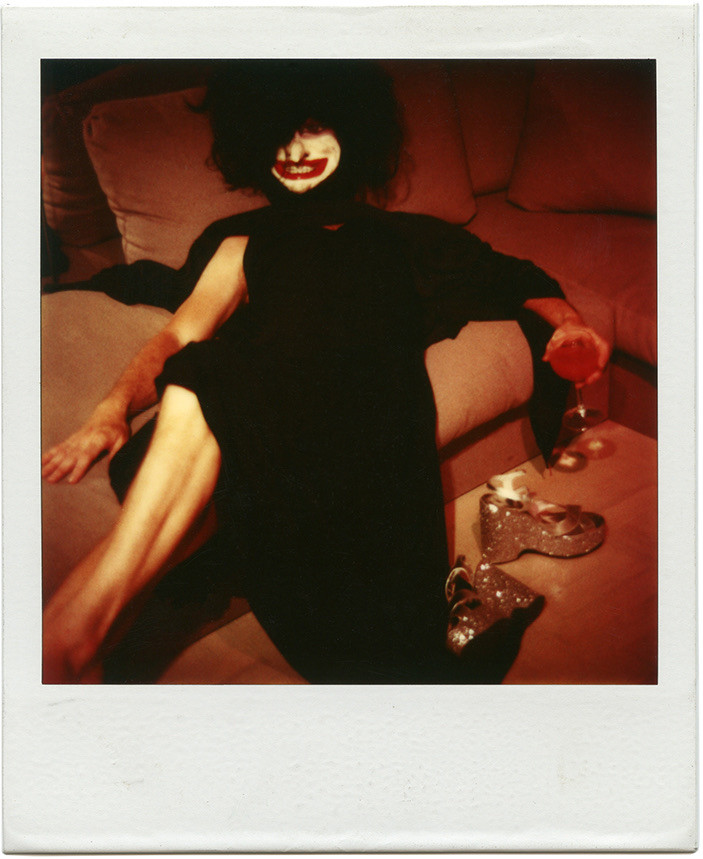

Back in the years 1975 to 1983, I had been given a SX70 camera by my employer, which was Columbia Pictures at the time, and I took the camera out to the beach and started documenting life in the Pines. And I really early on realized that I wanted to make a book of that material. I wanted boys like me to know that there was such a world that existed. At the same time that I was doing that, I had an apartment in Manhattan, 63 East 9th street, which is the title of the book, and I was photographing in the apartment at the time. The material was quite different from the Pines to the apartment, because obviously the apartment is a much smaller geographic space than Fire Island and the Pines, so it tended to be more concentrated, the images were, and skewed toward my and my friends’ intimate lives. And that material was pretty much hidden in that scene until very recently. When the Pines book was revealed, I also showed a few people the New York material, and we knew then that there was another book from the Polaroid material that I shot at the apartment.

Now this is all pre-AIDS, these years. It was a time when we were discovering the sexual possibilities of ourselves, heretofore that was an area fraught with issues—including the fact that we had to hide ourselves from society.

I’m so curious about the Pines and how it ended up being this gay mecca, and Fire Island in general—do you know anything about that, or did that just sort of happen?

Fire Island, particularly Cherry Grove became a place where creatives, particularly gay people went. You had people like Paul Cadmus, George Platt Lynes, Jared French going there to hang out. It was a place you could be naked and really free spirited. And as summers went on, it was considered a very bohemian place, there was a spillover into the Pines, which had been developing itself as a new community. Ultimately it became a community larger than Cherry Grove. It started with people floating houses over and then it turned into a place where people started building houses—quite wonderful ones, at that. It as a place for architects to expand their vision. And my apartment in New York, the design of it was influenced by the kind of lifestyle we were living in the Pines. I designed that apartment to be a place for sensual comfort, soft light, lots of banquettes, lots of mirrors, plate mirrored a wall in the living room, plate mirrored the ceiling in the bedroom.

Do you feel like the Pines contains a similar spirit today? How has it changed, or has it?

It can’t change physically that much—it can change with global warming with rising seas, it’s a sandbar after all. Socially, it was a place for creative types to find one another, and so it attracted from theatre, dance, fashion, all of the art forms. And that continues to this day, it’s still like that, it’s discrete in the sense of size—there are about 600 houses there, so there’s a limited amount of space, but it’s very concentrate in the creative communities. I find that people go there today for the same reasons that we went there back then: we wanted to connect with one another, we wanted to find one another emotionally, intellectually, sexually. That’s what we were looking for, and that’s what we found there, and that’s what continues to be found there.

Can you talk about your models and working with these nude men, was it sort of a silly fun thing?

I never considered what I was doing as shooting models, per se—there was never that kind of distance. For the most part the work was about my friends, and a number of those friends were also lovers. These were the days when we were probably more fluid about that, you’re talking decades before the idea of gay marriage. There were a lot of couples who were attached in a monogamous, conventional way, but sex was much more open and free flowing. I think it was more like it is today, in the post-Prep (Truvada) era, the fear has receded and it’s allowed people to express themselves more freely.

It definitely feels like there’s a second sexual revolution occurring because of the advent of Prep.

Yes, that is true.

What is your opinion of that?

I’m a man who lived through the epicenter of the AIDS crisis, and it was horrific to be as afraid as we were—the fact that the expression of love could be the transmission of this deadly virus. So being free of that fear allows us to essentially be who we really are. One thing about the gay community first, last, and always was it was attracted to itself because of sexual attraction, that’t the essence of it—and what we found in our queerness was a different kind of dialogue than what was going on in the larger world. I think the gay community was more acceptive of difference. Each generation has its own styles, but in general we were accepting of our queerness. And today, with the number of trans friends that we have, I see that expanded, if you want evidence of the breakdown of binary gender, the Pines is a place that fosters that and invites that, so that people can be who they are. I think this has a massive impact on the culture we live in, because we’ve been living in a culture that is male-dominated, restrictive, and judgmental, and hateful in fact. It’s been a very dangerous place for people who want to live outside that box, and we see now that we have to live outside that box—because what goes on inside that box, the toxic power tripping that goes on invades our political and social lives.

Do you feel like your photographs connect to this kind of sentiment that you’re expressing now?

They’d better!

How?

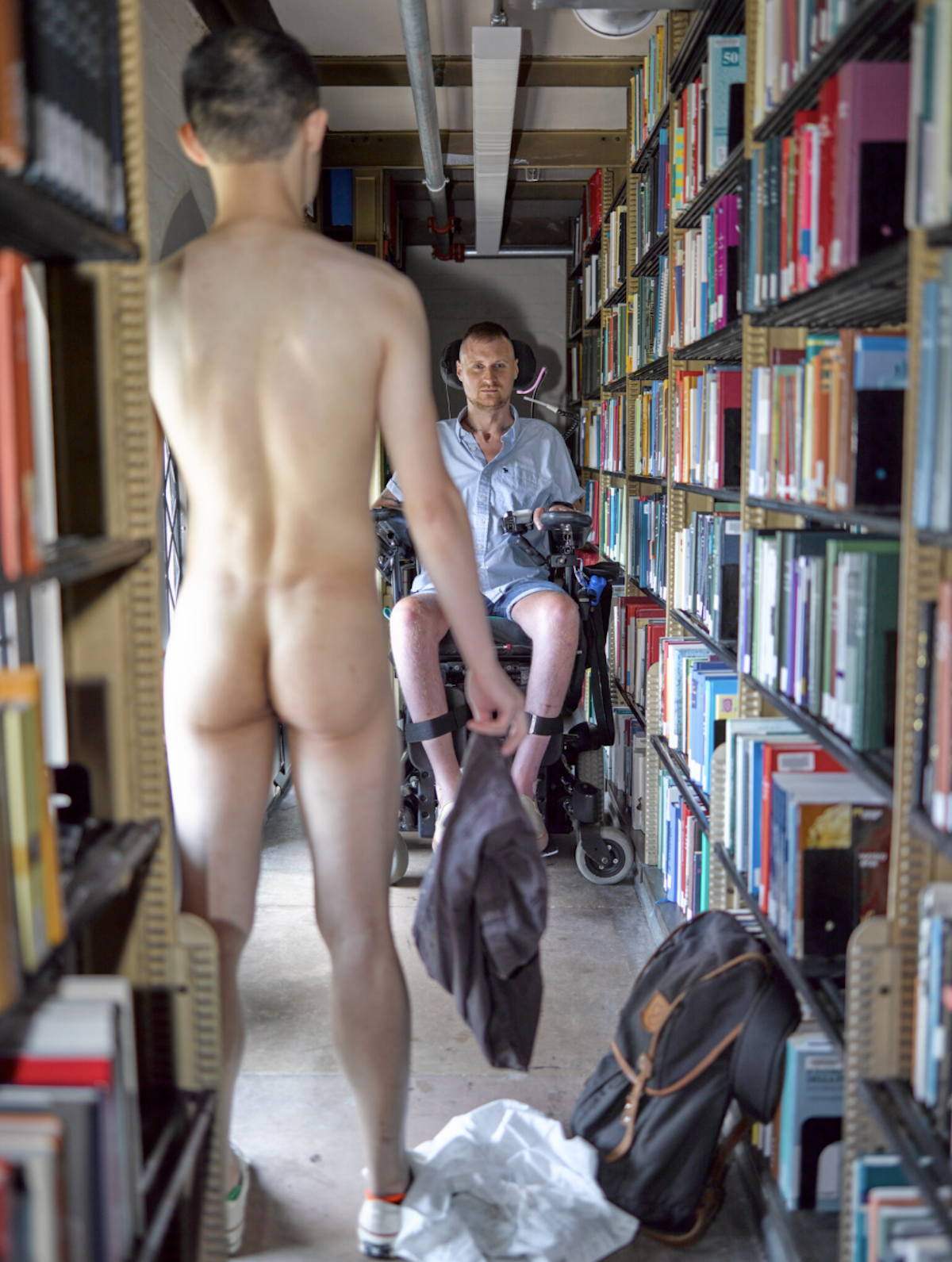

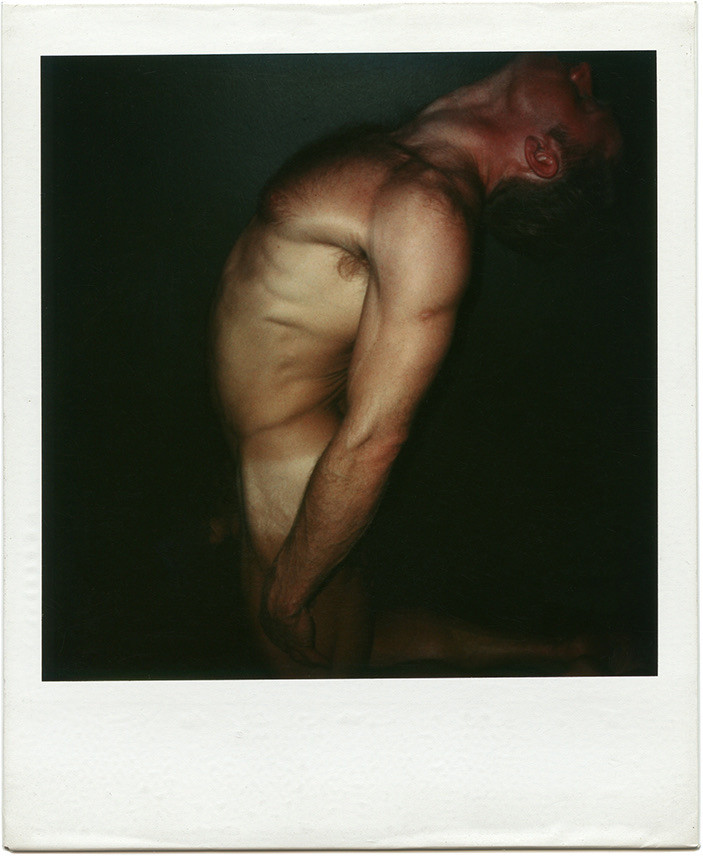

Here’s the deal: photography, particularly of the male nude that I came up with, was guarded and coded. If you look at the history of art, men were allowed to touch if they were in battle, or in extremis, you can look at all these classical paintings. When photography happened, photographers took up the tropes of classical figure painting, so there were models in posing straps—they had to be in posing straps at that time, because there was a fear of prosecution from the government. So all of that work, how we saw each other, was put behind a wall. We could decode it if we watched carefully enough and we could make assumptions about what might be going on, but we really couldn’t see what was going on. My aim was to tear down those walls of censorship, and show us as real gay men affectionately connected with one another.

My book, Out of the Studio, some have regarded as a breakthrough because it was clear that the men in those photographs were gay men, they were touching each other fondly, intimately, and it was very different from the fashion photographers who were photographing men and guarding the desire, the impulse that men had for one another. I’m happy to say that there are a lot of men today that have told me they felt liberated when they saw my work, that finally they saw themselves and their own desires reflected. And that was absolutely my intention. I knew how to take that photo of the idealized, statuesque male standing in isolation. That wasn’t a terribly hard photograph to make. But to find in the photographs a connection with the person that’s real meant that the people I photographed needed to be out, they needed to be comfortable as gay men. Fortunately there were a number of us that were comfortable enough to be in that state and be represented in that state.

Do you feel like your photographs in a sort of underground, select audience sort of way until recently—how would you describe the transformation of the audience, if there is one?

Well in 1988, I had a partner who died of AIDS, and I was a painter, sculptor in those years—I’d torn up my law degree years before. So I didn’t have a commercial photographic career to protect, as did a number of men who were photographing men, they had to look at their shoulders at what their clients might think.

So you had a certain level of freedom.

I was free of that, yeah. And very fortunately, I also found myself in the hands of a brilliant editor, Micheal Denneny. Micheal was the first gay editor who had his own imprint at a major company, it was St Martin’s, and Micheal recognized that the photographs I was making were very different from the photographs being made at the time—they weren’t studio photographs, they were real photographs with narratives, they had stories. Today he’s considered one of the top people in gay literature because he published writers such as Edmund White, Paul Monette, Randy Shilts. He took down the artists and writers who were chronicling HIV and AIDS. So my first book was a statement of hope in a very dark time. That was published in 1990. It was hugely successful book. I don’t claim that the book’s success was a function of my genius, it was a function of the fact that the world desperately needed a healthy vision of itself, because the world was living with such horrendous images of ourselves and our friends in various states of extremis and decay. And the fact was, it went mainstream immediately. We were in the windows of the best bookstores in the country. So it was never an underground thing, it just burst through to mainstream right away. Micheal told me the other day, I was visiting with him, it was the most successful book financially in the non-fiction category. But as I said, if you find a need and you offer to fill that, that’s where success lies. If art isn’t prompting you to live differently, if art isn’t prompting you to think differently, it’s missing the point I think.

I have to ask—there seems like there’s a fine line between erotic photographs and straight up porn. I’m sure you’ve had this conversation, but how do you dance that line, is it just a marketing thing? What is your opinion of porn?

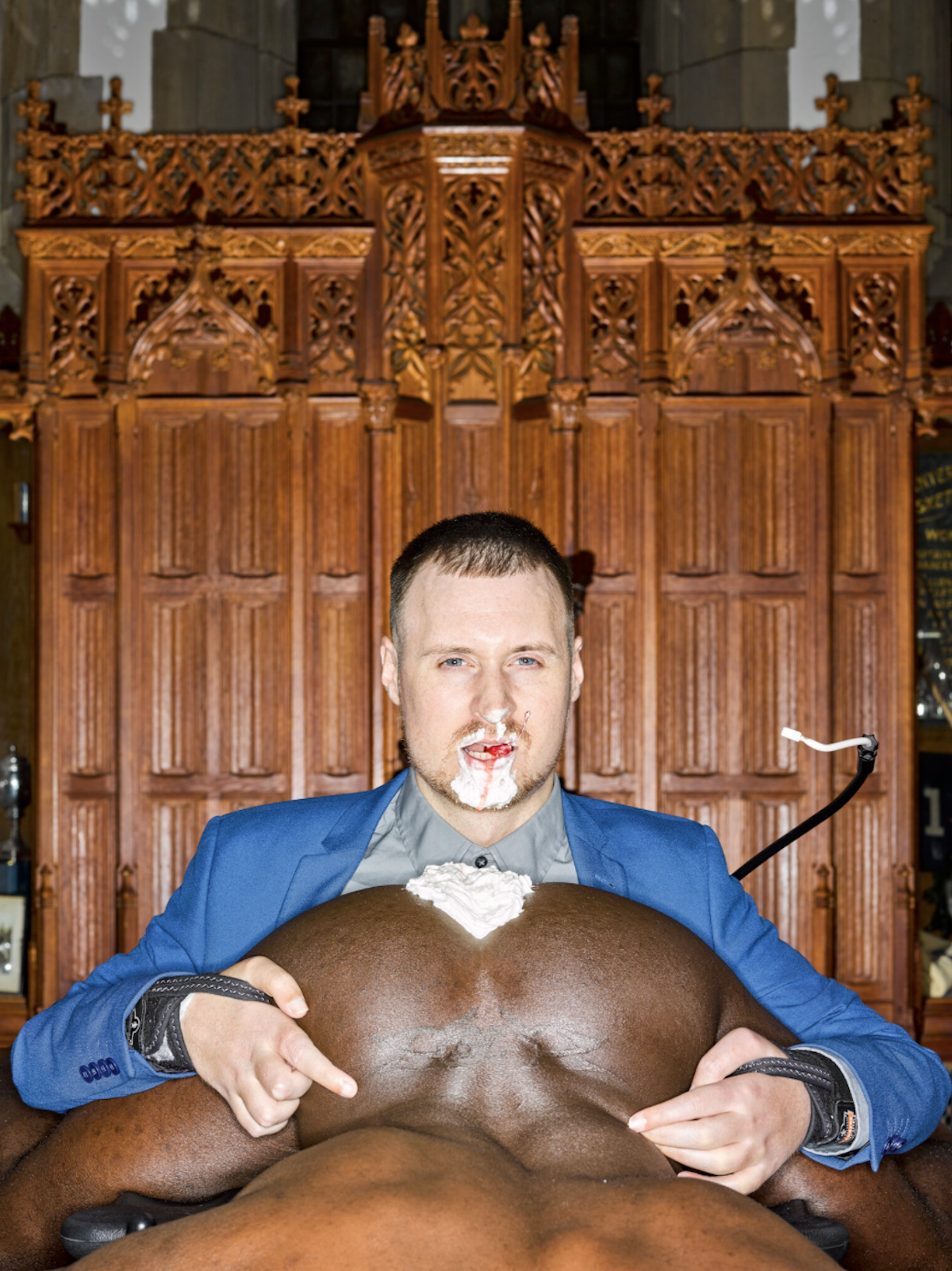

First of all, the word ‘porn’ means ‘writing of prostitutes,’ it’s from the Greek. It has a pejorative, negative context. But when photography was invented, one of the first things artists did, or people with cameras did, was photograph nudity and sex. It was the first time that the culture with, ‘Oh my God that’s really somebody doing that.’ A lot of people couldn’t deal with that, so they decided there would be this negative category, unwholesome, sinful, whatever. My own philosophy of life—and I’ve stated this many times—is there is no such thing as pornography. There’s nothing in God’s universe that we are not permitted to see. There are, however, bad camera angles. So sometimes I see the representation of sex is ham-handed. You can tell, you look at pictures and you see boys in specific attitudes and postures, in kind of a leering way, almost in the way you see a naughty girl fingering herself or something. It’s deliberately lurid. Now, I would not say, ever, that somebody should be censored for doing it that way, I just think it’s a rather simple-minded way of doing it. It’s like, ‘Come and be naughty with me.’ Now, there’s no doubt about the power of the forbidden—because if you forbid something, tell a child, ‘Don’t touch anything on that table,’ you can be guaranteed that the glass will be moved and broken, it’s the way our minds work. We create obsessions with what we forbid. And I felt very strongly that we needed to celebrate sex and sexual energy as a spiritual positive. So in my own work, I look for honest moments of connection, and I know that as an artist, if you’re going to move the ball down the field some, you’re going to have to push boundaries, you’re going to have to show something that hasn’t been seen.

So I’m looking for the erotic in detail, I’m always looking for ways of seeing that haven’t been commonly seen before. For example, in this show, these Polaroids had all been taken in my apartment and they were very much about sex, no question about it. But I’ve employed a number of devices which come from my own findings of what’s beautiful—figures in chiaroscuro light, figures connected, figures playing. We played with the idea of erotic wrestling. When I was a boy the only way I was allowed to touch another boy was to wrestle in school, and it was a profoundly erotic exercise for me. So one of the things we did was make pictures whose departure point was that kind of wrestling behavior, and that inevitably led to flat out sexual play. That couldn’t happen at the time in the art world, but I wanted to break down that taboo, and say, ‘Hey, let’s get real about this, this is what we’re really up to.’ And hopefully the honesty of that and the fearlessness made models for all of us to jettison our negative feelings about this.

Do you feel that you were successful in tearing down those walls?

When I know I’m successful is when somebody comes up to me, introduces themselves, and says, ‘I’m really glad to meet you because you helped me find myself—your pictures are the first pictures I saw that suggested to me that I wasn’t alone, and you helped us free ourselves of sexual shame.’ A number of people have told me that they see the work as being a very positive force in our community because it’s helped free us from sexual shame.

I recently watched the movie about Tom of Finland, and people would go up to him and say the same thing, like you’ve really set us free in a way. It’s almost like you’re a photographic Tom of Finland.

Tom of Finland is an interesting case because the image of a queer man. a gay man was the image of a pansy. These phrases like ‘light in the loafers,’ those were the pejorative terms used to describe us. But secretly in our heart of hearts we were attracted to men, to masculinity, and to its expression. So Tom of Finland, out of his imagination, created this universe where these hyper eroticized male figures were actually all having a lot of sex and fun with one another. That work influenced a lot of people—you can see it in a party today, a room full of boys wearing harnesses with muscles, that’s because of Tom of Finland—he invited us to be that for each other, he invited us to be each other’s sexual fantasies. The goodness of that is you don’t have to actually be a storm trooper, you could be a sales clerk at Bloomingdales selling men’s perfume, but at night you’re in your harness playing out at the bar.

'63 E 9th Street' is on view at Johannes Vogt through July 5th. Images courtesy of the gallery.