Full Steam Ahead

Indeed, this is the point. After I made my quick circle around the environment, Arlene explained that it was meant to be thought of as just that: an environment, not merely a collection of objects.

Most artists, when commissioned by Madison Square Park, use the lawn to display their work—not Arlene. She told me she she didn’t care for this tactic, that planting an artwork on the lawn was just mimicking the experience of a gallery or museum, in that it removes the work from the viewers, making it faraway and precious. She wanted to push against this preciousness—in the more urban, paved center of the park you can touch the sculptures, whose materiality is a large part of what defines them, and something the artist emphasized heavily: real wood, real iron, real porcelain. These sculptures ask you to interact with them, to become a part of their world by lending your body’s shape to the overall composition.

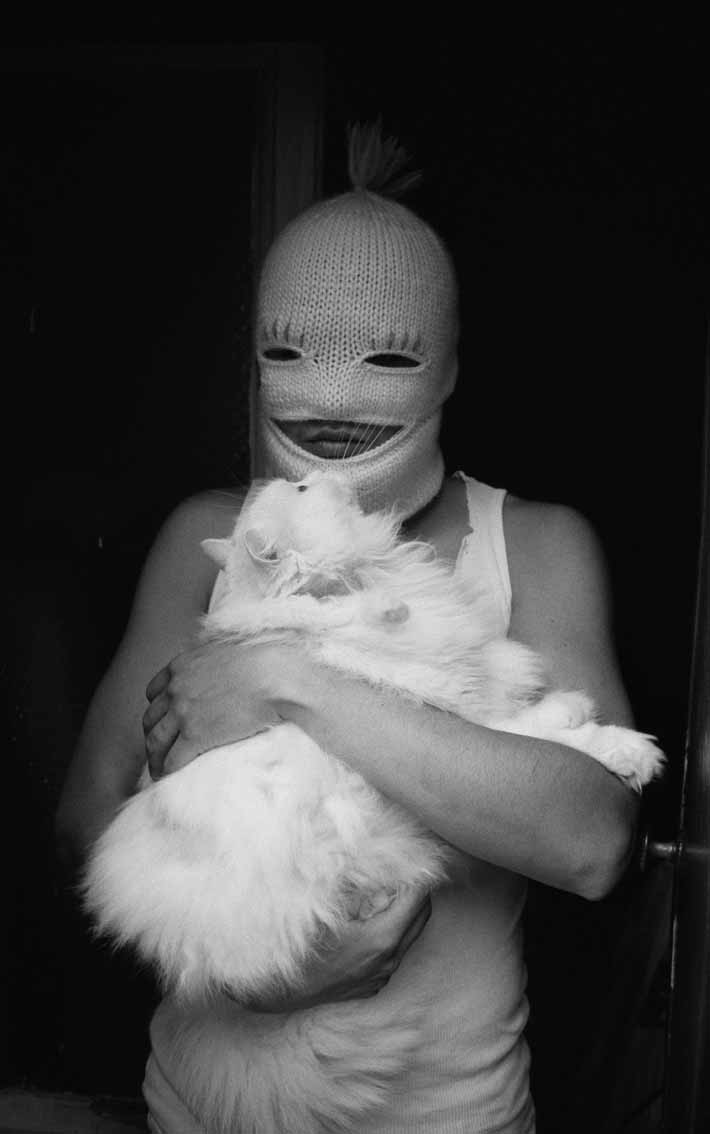

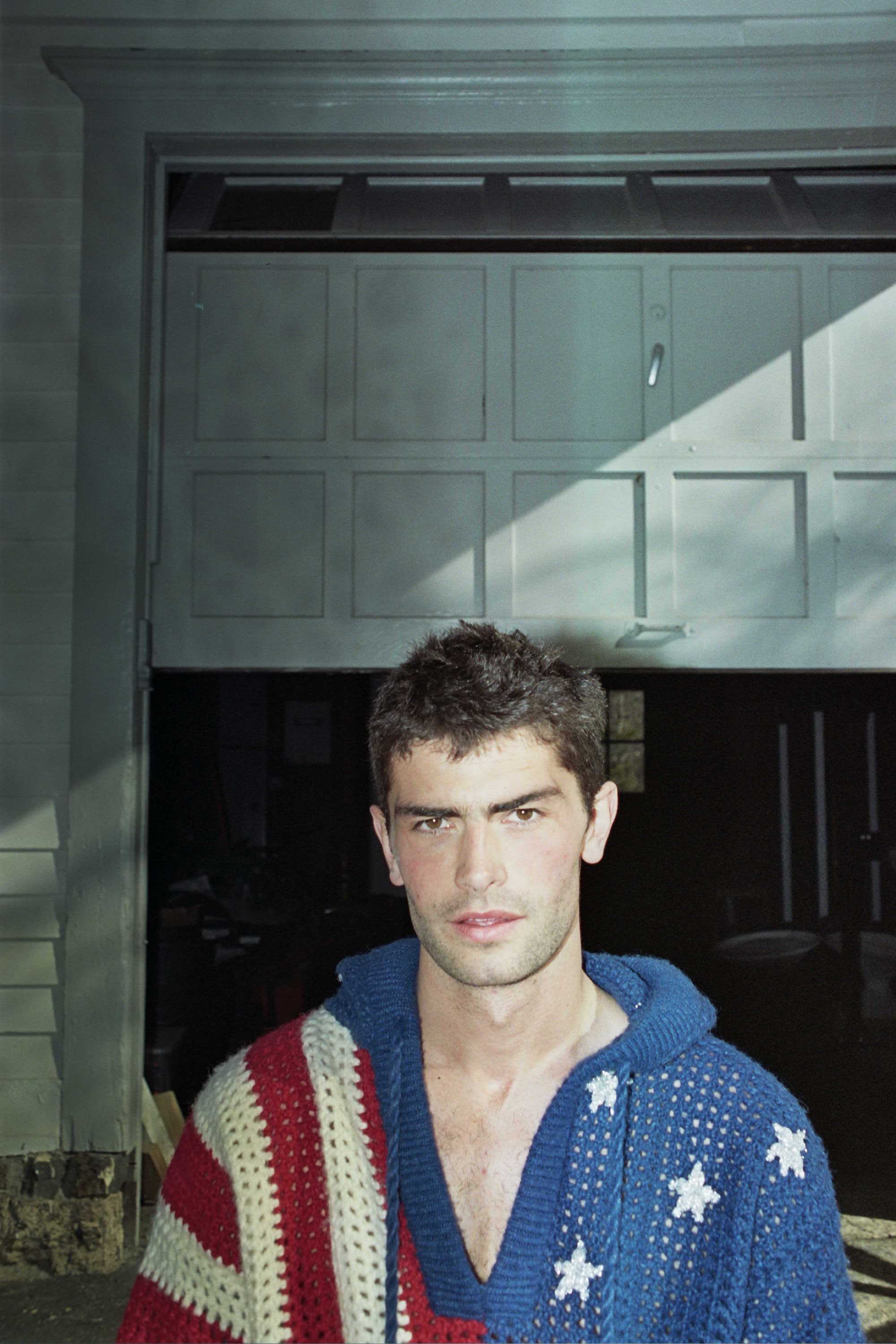

Above: 'Low Hanging Cloud (Lion),' 'Kandler to Kohler' and 'Channel Liberty (with Fallen Arm).'

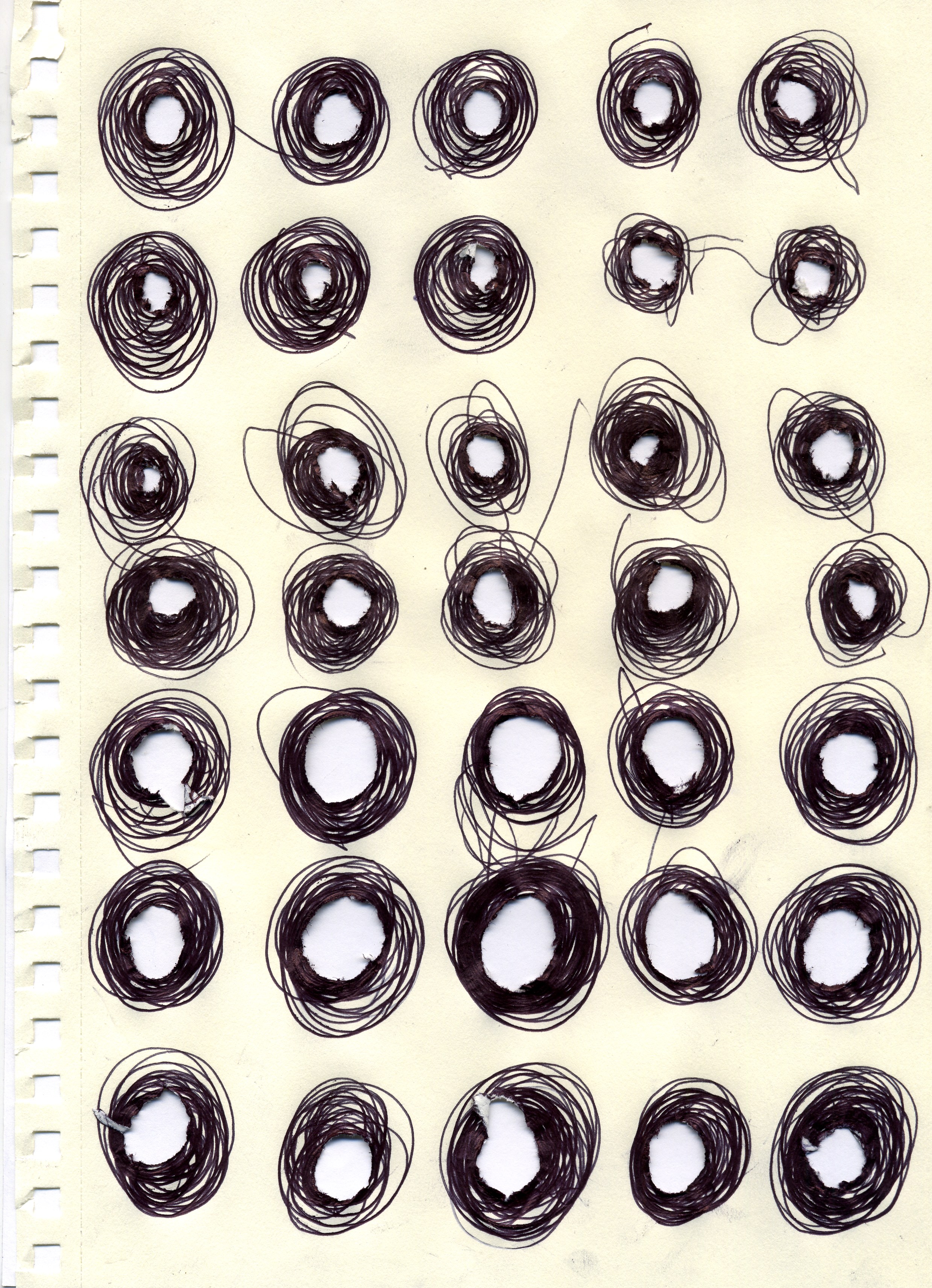

One compelling element of the installation is the removal of not only the water from the central circular pool, but the removal of the tiles therein. The artist explained to me that, over several months, she had photographed where water tended to puddle up in the drained circle, then placed reflective tiles in these places where the water would naturally pool. She calls it the "Shadow of Water"—an homage both to the water that would otherwise be there, and to her artist’s hand in mimicking it. Water was the original mirror, Arlene mused to me, and New York is hollow, carved out by tunnels underneath our feet—when you look down into the reflective world of the tiles, it's as if you look both at yourself and down inside the city upon which you stand. Again, you inadvertantly become a part of the piece, in the same way you are a part of the city.

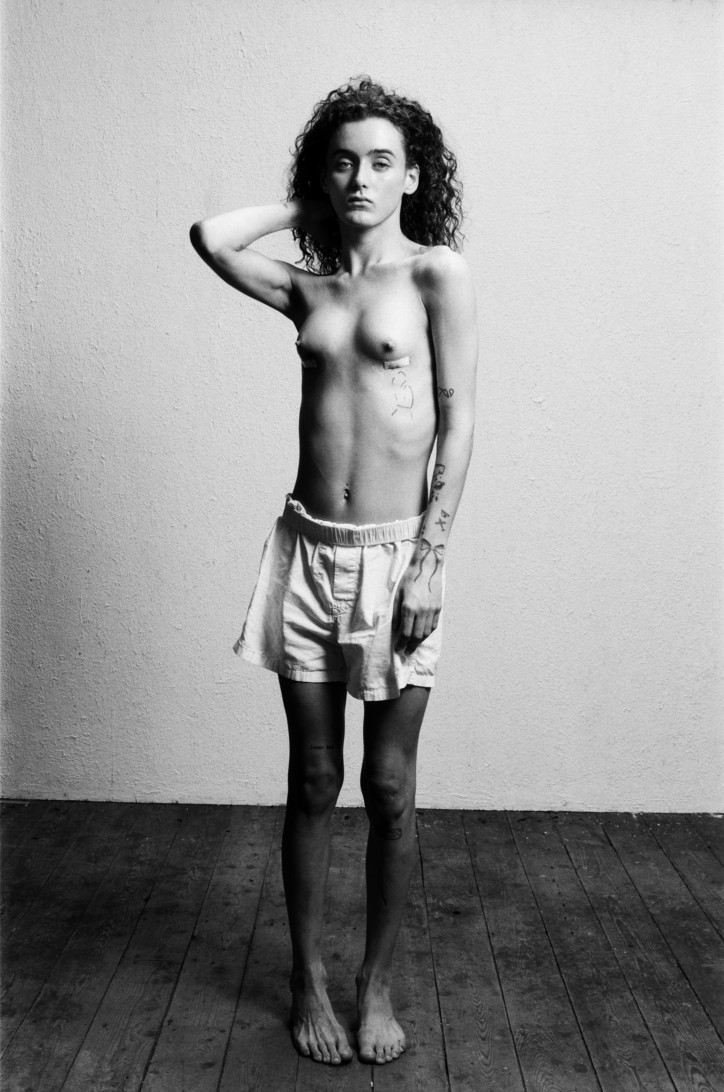

At one point, she led me over to one of the central pieces: a huge fluted white porcelain flourish, the base of which can function as a bench. The porcelain pieces are record-breaking—she worked with the manufacturer Kohler to produce them, and the lion’s head alone is 34 separate pieces that had to be fused together. Jeff Koons’ sculpture of Micheal Jackson and Bubbles was the world’s previous record-holder for largest porcelain sculpture, but here Arlene has beat him—and at the risk of their destruction (their exposure to the public and the elements makes them challenge the idea of preciousness on a scale that would make most artists squirm).

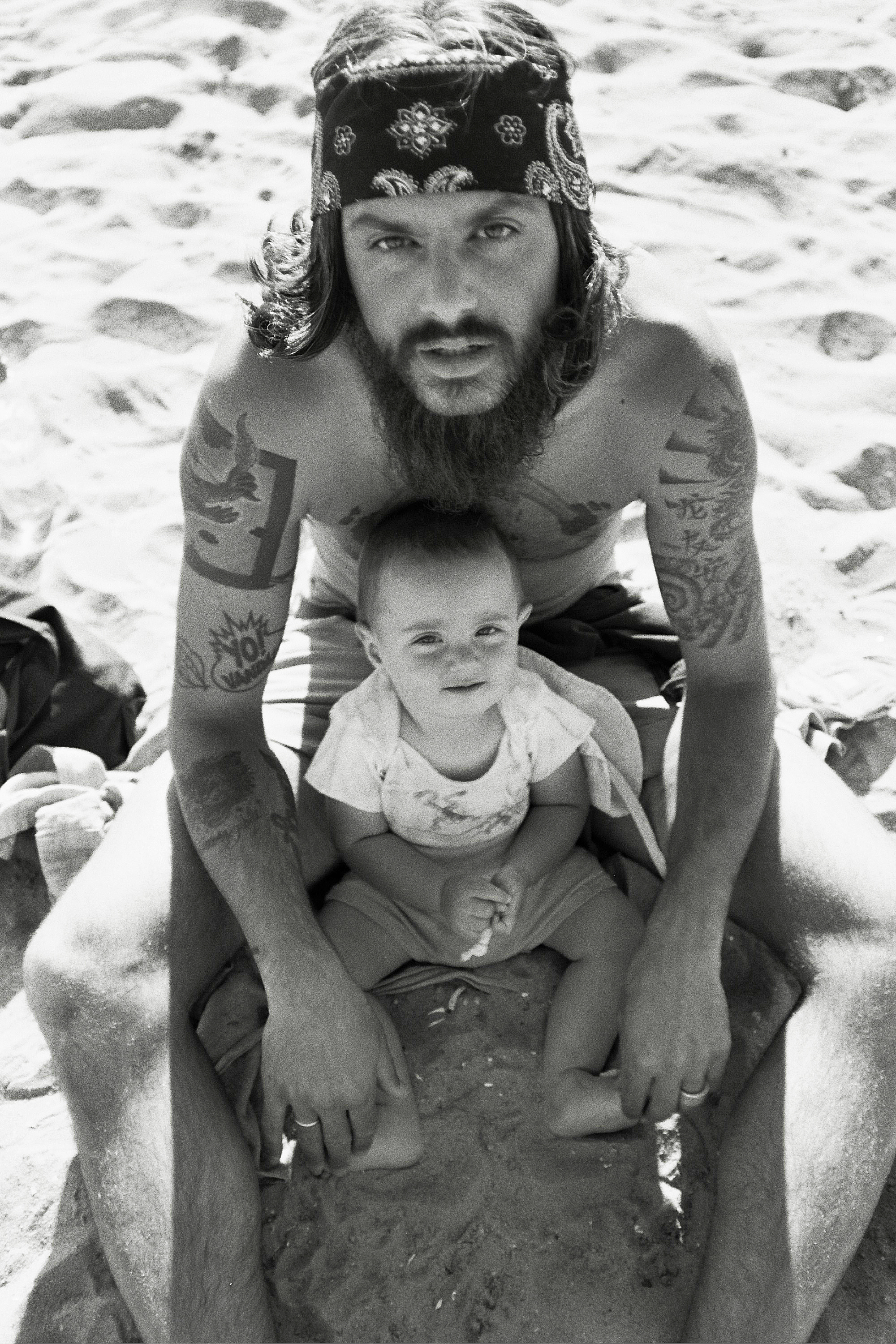

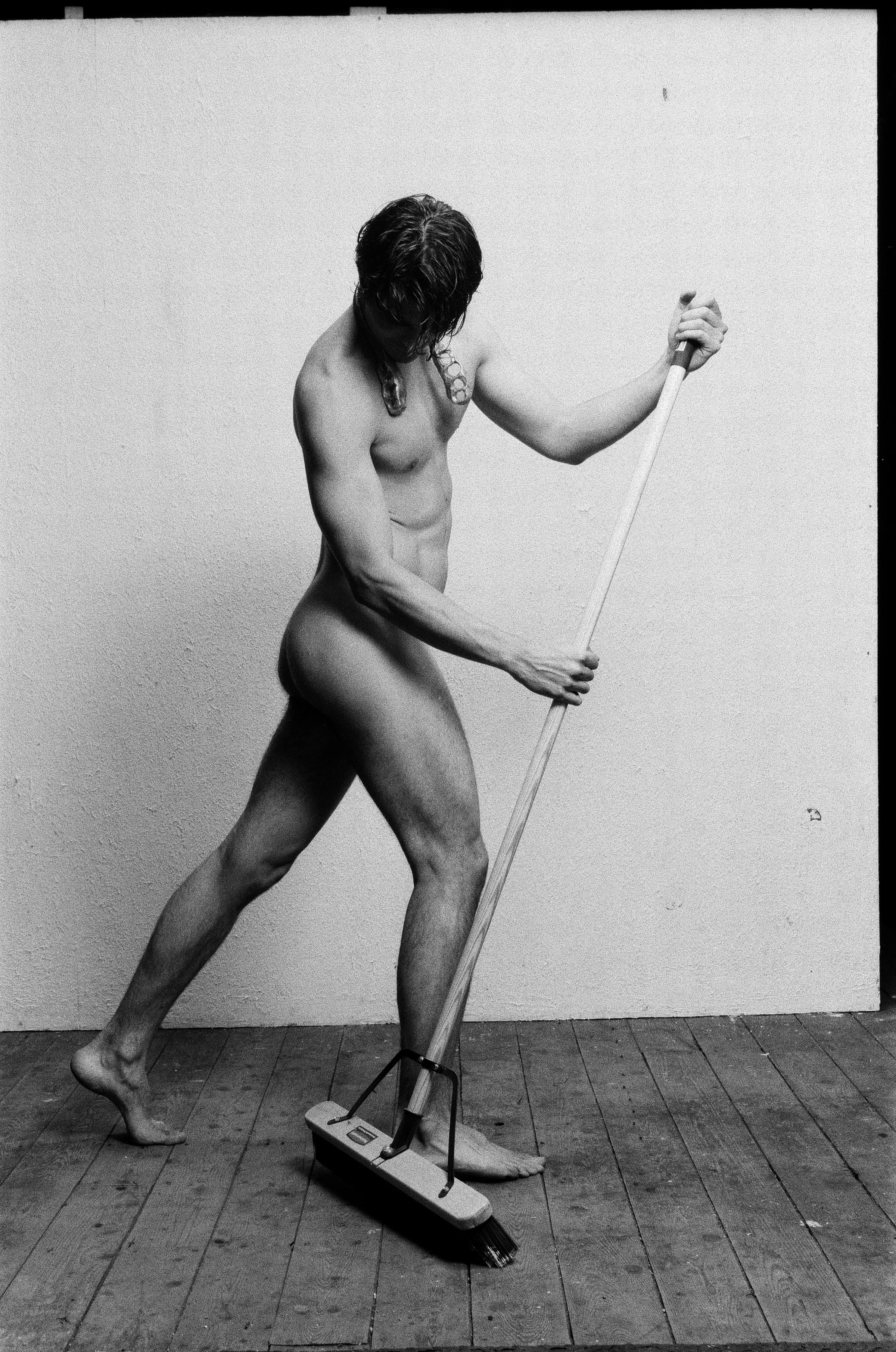

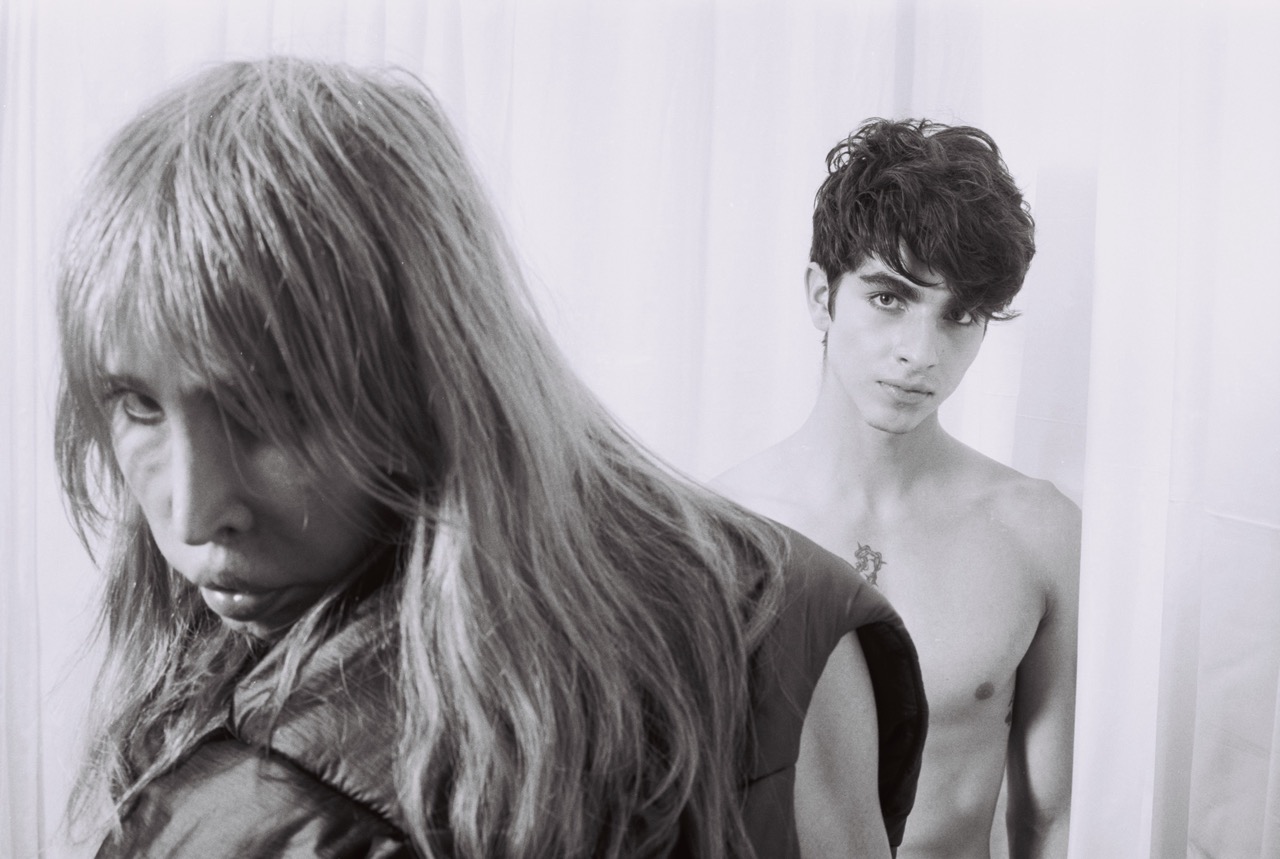

Above: 'Forward' and 'Full Steam Ahead.'

On the ground where we sat was another circle, which I thought looked like a planet—in fact, it was a blown up glaze from another one of her works (more mimicry!). When I told her it looked almost accidental, she nodded emphatically—a glaze is a natural process, after all, and its reference to something both planetary and accidental is a connection she can personally appreciate. What is nature but a planetary accident, anyway?

The sculptures themselves are strange, organic and jocular—I was particularly drawn to the removal of the bench slats and their replacement with black and white planks. The color scheme, I said, reminded me of Alice in Wonderland. Arlene smiled, telling me that the benches were in fact the through-line of the installation. She then said something I won’t soon forget: that she didn’t see why humor and joy couldn’t coincide with intellectual rigor. I couldn’t agree more.

Photos of the artist by Yasunori Matsui; installation photos by Rashmi Gill; all courtesy of Madison Square Park Conservancy.

'Full Steam Ahead' will be on view in Madison Square Park through April 28, 2019.