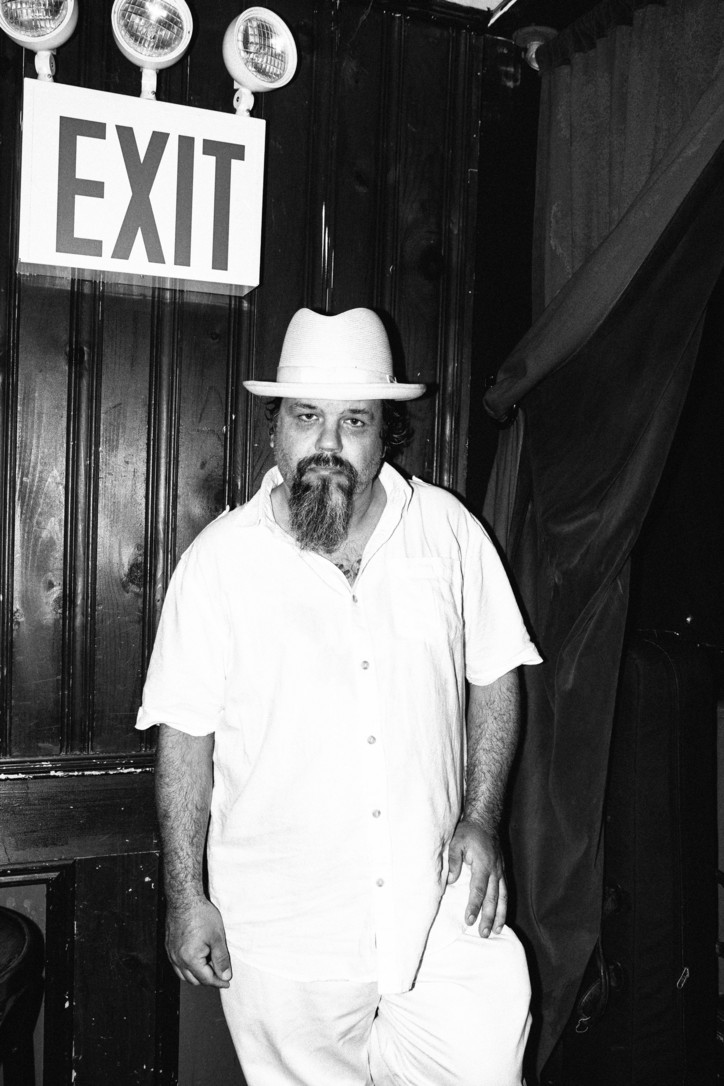

Bohemian Rhapsody - Reverend Vince Anderson

Office — What are your first memories of religion?

Reverend Vince Anderson — Well I was born in California. I grew up in Fresno, land of raisins and crystal meth. Growing up I was raised Lutheran, and I think my first memories were two things. One, the pageantry of it—stained glass windows, big ceilings, the physical stuff. And then the social aspect. It’s interesting, the church I was raised in was in the Valley in Fresno, and there were quite a few Midwesterners, specifically Minnesotans that’d come looking for a better life in agriculture, and among them were Norwegians and Scandinavians that were Lutherans. So this church actually had services in Norwegian when I was a kid. The Norwegian was more of a tradition than a necessity, the long-past cultural remnants of the ‘70s immigrant population, but that made an impression on me, this gathering, this mixing of cultural identity with religion.

O — Were you introduced to music through religion?

RVA — The Lutheran service is primarily sung, so there weren’t too many religious declarations made as a child that I didn’t sing. I started playing piano at a very early age in the church, and then family life—it seems like a horrible cliché, but as a family we would sing. That was our Friday night entertainment, we would sit around a piano and sing from this big Reader’s Digest book of old classic American songs. I have vivid memories of my dad singing Shenandoah with my mom accompanying him, and me and my brother attempting to do really bad harmonies.

O — But you recall that with fondness? You weren’t being held against your will…

RVA — I do recall it with fondness. Despite all my problems with the church, it’s always been, for me, one of the very few places where people sing together. That I always loved. As a kid I loved singing hymns and hearing all the voices around me, and hearing people attempt to do harmony. It wasn’t about the quality, it was almost like the badness of it, the brokenness of it somehow gave it more beauty. There weren’t glee clubs, or different places where people casually got together and sang, so for me, between the church and the family, it was pretty commonplace. I never really realized that a lot of people don’t do this, until I was older.

O — Why do you think that is? Why don’t we have more group singing outside of that context?

RVA — I think the main reason is that church music was never recorded. So you can’t find that many playlists of hymns. There’s the gospel tradition, which was widely recorded, and things like that, but I think for my generation, anybody that grew up after recorded music, popular song was transmitted through recorded means rather than being played and sung. There was a point when popular song was transferred via oral tradition or sheet music, and if you wanted to hear the song that people were dancing to at the Waldorf Astoria before recorded music, you had to buy the sheet music and play it. I’m not a Luddite by any means, but I do think that with the proliferation of technology and media, music has become more and more of an isolated act. Our relationship with music is each of us with headphones on. It’s a private thing, and I think that’s been a gradual shift since the dawn of recorded music.

O — So you were involved with music with your family, and with your church—did you have a band? Were you into rock ‘n’ roll as well, or was it mostly spiritual music that interested you?

RVA — You know, I was pretty wide open as a teenager. I had a little funny rock band, and so I certainly was never against music outside of the church. I never viewed it as a dichotomy, but it did seem like I felt a weird kind of freedom within church music that I was especially comfortable with. For me, music is a channel to whatever we call this mystery, this spirit, this something bigger than us. I call it the Holy Spirit, just cause I’m a fan. Music was always a vehicle to lose yourself and discover something different, and to me that was always holy, no matter if it was screaming in a rock band or being prayerful and meditative in a choir.

O — So was it that same goal, to find something beyond yourself, that lead you to seminary?

RVA — It was a few things. It was certainly that, this kind of identification or affinity with a mystery that seemed to capture my imagination. Religion started to feel like the greatest piece of art possible, the fact that it was said from the get-go that it was a mystery, that you don’t really know. To me that’s an amazing place to start a creative endeavor. The other reasons for seminary—I certainly felt called somehow to enter the ministry, and part of that call was this desire to acknowledge something bigger. Also, as I got older I was really attracted to the humanism of Christianity and of religion. I started realizing ‘Wow, this is all pointing back to humanity.’ So much of religion had been pointing away from humanity, for us to escape our own humanness, and transcend our humanness. “Sinners in the hands of an angry God.” That we’re sinners and we need to transcend that. A lot of my religious processing was in reaction to the birth of the religious right, and this idea of born again-ism. I found it odd that when you’re born again, you’re born as something less than human, this creature that has no desires and nothing of the beautiful quirks that make us individuals. You’re born again and suddenly you drink in moderation? You’re born again and you’re nice to everybody? No, those cracks in our humanity, that is our humanity. These things appealed to me, and were all reasons that I felt called into the ministry.

O — And why choose a seminary in New York?

RVA — One, I was fascinated by cities, and I knew I wanted that. It didn’t feel right to go to a suburb on a hill for seminary. Especially with my idea of humanism, I wanted as many humans as possible. The other reason was that Union Theological, were I went, was an independent seminary at the time, it was free from any denominational bonds, and it was the only seminary that fully welcomed LGBTQ folks at that point, and that was really important to me. Now mainline denominations have made great strides in welcoming people—I feel like they’re a little on the taillight than the headlight—but at that point I wasn’t going to participate in a system that seems completely contrary to what religion should do.

O — But you didn’t finish your studies there—what took you away from it?

RVA — Once I got into seminary, there were a couple things that happened. One, the academic pressure was more than I expected. I thought I was coming into a place to learn a job, but seminaries are academic centers. Which I love, but the rigors of it seemed to suppress my creativity, and at the same time, because of the threat of suppression it rebirthed the artist in me. I talked earlier about a born again experience, well this was a different kind of born again experience. It felt like God, or this mystery we call God, I felt like that entity called me out of seminary. That was a very ‘Road to Damascus’ experience that I haven’t really had since then, and twenty-four years later, to me it still seems real, it still has some validity in my life, even though my theology has gone different places and changed, that moment of feeling like I have some direct connection with whatever this thing is, that said “Go. Leave.”

O — Do you think that call to seminary was just fate’s way of getting you to New York?

RVA — Yeah in retrospect, sure. I think the life I have now is a direct result of God saying ‘Yes,’ and then saying ‘No.’ And me listening to that. Because after that, I took a job at a church in Queens, and started singing in clubs for the first time in my life. And in these clubs I would sing gospel songs, because that’s what I really knew how to sing. Pretty soon I started getting a regular gig somewhere on Avenue B in the East Village, and sang there just solo piano every Sunday. This was a few years after I’d dropped out of seminary, and I was really still kind of pissed off at God, you know ‘You dragged me twenty-five hundred miles…what the fuck!’ I had a moment—more than a moment—of rebellion. ‘Now I’m in the East Village in the mid-‘90s, great. This is going to be my life now.’

O — Yet still singing gospel…

RVA — Yeah, because that’s what I knew. I found that you launch into This Little Light Of Mine, and people respond to it, they love it. If you’re going to connect with people, the best way to do it is with something you’re passionate about. So I started singing gospel, and one day I come to my gig and the New York chalkboard marquee out in front of the bar said “Tonight: Reverend Vince Anderson.” And nobody knew my story, I wasn’t broadcasting that I had dropped out of seminary, that wasn’t part of my deal, but that was just how the bartender identified me, you know ‘Oh he sings gospel, we’ll call him the Rev.” Pretty soon that lead to playing every week for a community that developed around those gigs, and pretty soon that community started asking me if I would baptize their kids, and bury their dead, and marry them. That’s when I started realizing ‘Maybe this is the call.’ It felt very authentic in the sense that a community was claiming me as one of their own to do the ecclesiastical things that they needed done. My relationship to my community is really important to me. They see you in a way that you probably can’t even see yourself, and identify something in you that you might not be completely ready to do. Certainly that was my case.

O — There’s a concept of God right there in that dynamic.

RVA — Mhmm. And kind of a reluctant apostle, that notion of ‘Yeah, not so sure about this one.’ So that’s kind of where I claimed my call, and it developed in several ways from that moment. I was reluctant at first, because I was still pretty angry. ‘Oh, so this is my call, great. You put me up in a bar in the East Village in the mid-‘90s, with all kinds of characters. This is it? Where’s the paycheck?’ So there was a reluctance, and that reluctance hung around really until September 11th. I was performing a gig on the 16th, right after, and that’s when it really felt like I was a pastor. Having conversations with those who had lost people, or who couldn’t find people at that point, that’s when it became really clear. They’re bar people, they’re never setting foot in a church, but here they found themselves, like ‘Okay, this guy’s singing about something bigger, maybe I should talk to him.’ And I don’t claim to have the answers, for me faith is the opposite of having answers, which puts me in the same boat you’re in. I’m just as pissed off and confused as you, so let’s talk about it. That’s when the gigs started feeling like church, in a beautifully broken, ragtag way. Some people might call it heretical. It connected with people, to reclaim gospel songs that are sung by human beings about human concerns. These are real cries. It’s one thing to cry about your boyfriend or your girlfriend that broke up with you, and to sing about that, and that’s terribly important. But then the pathos that comes when that song moves from being angry at a girlfriend to being angry at your ultimate concern, or God, then those songs become almost hyper-human. They become almost operatic in their pathos.

O — Did you have any trouble performing at these bars, which are traditionally seen as ‘dens of sin’ or whatever, and reconciling that with a show that was feeling increasingly more religious?

RVA — There’s nothing different between a mass and a rock show, in a lot of ways. A rock show uses lighting, loud music and drugs. A mass uses a really elaborate gigantic organ, candles, incense and wine. It’s sensory, and there is this ecstatic notion to it. And I mean, I lived through the mid- ‘90s of the East Village, I had my share of partaking of the communion that most would call vice. And as with all things, the sin is in that, but it’s not it. Religion itself can be a sin. If it separates you from each other and from yourself, then yeah, that’s a sin. Same thing with drugs, and alcohol, and sex, if it separates you from yourself and others, then that’s a sin. There are two ways to go about it, you can either say ‘I renounce all the world, and its sin,’ meaning vices, or ‘I live a rock ‘n’ roll lifestyle’ and go straight into it. When you do either of those things, that alone becomes your driving force, rather than your driving force being the question of whether you’re connected to your neighbor, whether you actually give a shit about the person you’re sleeping with. Those are the questions that are more important, and I think a lot of times people look to vices, whether drugs or religion, as a way to not answer those questions. It’s too bad, because on the other side, those same vices can lead you to great wisdom, whether it be rock ‘n’ roll or church, doesn’t matter. The question is, what are you in it for? Financial capitalism and spiritual capitalism are the same damn thing. They’re both looking out for yourself. So whether you decide you’re going to go the way of Gordon Gecko or your going to go the way of Pat Robertson, it’s the same thing. You’re climbing a ladder rather than caring for the people in front of you.

O — There’s something especially ironic about wanton selfishness in the name of Christ.

RVA — Yeah, I mean Jesus said there’s two commandments, love God with all your heart and all your soul, and love your neighbor as yourself. I kind of believe he meant it, you know? Live in the mystery, so you don’t get caught up in the minutia of human life, but then learn to love a little better than you did the day before. Love your neighbor as yourself—it’s a cliché, but it’s a great statement. Everything you need to know about how to be a human is right there.

O — Do you find you have a particularly unconventional ‘congregation,’ if we can call it that?

RVA — It’s interesting, but I think a lot of people think I’m joking. Because religious stereotypes are perpetuated not only by the religious. It always cracks me up when someone apologizes to me for cussing in front of me. Like, ‘Don’t fucking worry about it,’ it’s not what I’m concerned about. People come to me with certain expectations, and maybe some of my role in a priestly function, or as a pastor, is to blow those expectations away, to a certain degree. So I do get people that want to just fight with me. And I love that. I love hearing people’s stories. Even with me, a very untraditional pastor type, people are guarded. It’s like ‘No, really, I’m not trying to convert you. I’m not trying to get you on my side. I’m genuinely interested in your story.’ But I have little patience for people who guard themselves in these discussions, out of respect for me. Treat me as a human being, and I’ll treat you as a human being.

O — It sounds like you also sometimes serve as a shrink in a way.

RVA — I’m the guy people come to to talk about this mystery, and either how they feel disconnected, or they feel judged. I think a lot of times people come to me that might not have any inkling of spirituality, and they come just to hear me say that they’re not going to go to hell. Which is strange, but it seems like a lot of times that’s what happens. I don’t have any belief in hell at this point, I barely have any belief in any kind of life beyond this. I hang on to heaven, just because I’ve sung too many gospel songs about it to let it go. But with that said, I don’t know. I’m worried about this life here now. It works both ways, I have plenty of people who come to me who were raised in a religious home where there was lots of violence perpetrated against them, where they were really damaged. Either by being not accepted because they didn’t fit the mold, or told that God didn’t love them, whatever it is. So sometimes my role is to usher them out of religion, or usher them out of a belief in something bigger. Like, ‘No, you don’t need to worry about this right now. This concept of God that you’ve been taught has fucked with you. So yeah, you have my permission, if you’re looking for it. Just leave.’ Whatever this thing is, it’s a concept. You can destroy your concepts. Human first, everything else second. – END

Interview Marc Palatucci

Portraits Alessandro Simonetti