The Habibi Collective

One such adventurer I have come to know is Róisín Tapponi, an Iraqi-Irish film curator, film programmer, and writer, known to many inquisitors as The Habibi Collective. Róisín has single-handedly created one of the most comprehensive archives on the internet on South-West Asian and North African film, period—but the specific mission of The Habibi Collective is to act as an archive for women filmmakers from the region. The Collective is far-reaching in its implications and archival value. And, as it is staged on Instagram, it has an international reach on a massive platform available to anyone with an Instagram account, circumventing the exclusionary nature of academic and artistic institutions. With almost daily posts of movie stills, videos, presentations, and online screenings shared directly with over twenty thousand followers, the outreach rivals decades-old institutions. Róisín is possibly one of the most successful contemporary film curators in what she has created and proven with The Habibi Collective.

And the emotional gravity, too, of the project is almost as valuable as its successes. It's an instant, approachable archive to culture unavailable to entire generations of both those living in the diaspora as well as those without access to institutions in the region. The Collective is a bridge to culture kept away by distance, politics, and trauma. What once required academic resources or institutional support is now available in your pocket. It’s a project of healing. And it began, exists, and will remain all on Róisín’s phone.

On almost a daily basis, I see people I follow within the diaspora share something from The Habibi Collective. Often, I see people who have never met each other, in different parts of the world, share the same post. And when one does post something from The Collective, it sparks a dialogue, usually difficult to begin in the first place, about the art and culture we all, as one, are searching for. And that’s perhaps one of the most shocking parts of all, that the entire “Collective” so-called is all done by Róisín. Something so significant to so many people is performed by one single person. Entire conversations around culture building begin because of what Róisín decides to post one day.

And I wondered about that throughout writing this article, but never actually got the chance to ask Róisín about it: why is it called The Habibi Collective if it’s just one person? I have begun to interpret, whether this was the intention or not when she began it years ago, that perhaps it’s because we, all of us that receive the archive, are a part of the Collection. Róisín, in real-time, is performing the priceless labor of diaspora building, collectivizing us in spite of the borders that have separated us.

I spoke to Róisín over Zoom, me in Los Angeles, she in her London flat, an appropriate accommodation for a conversation about what is possible at a distance. We spoke on The Collective, future projects in film, and Róisín’s background in journalism.

Hi Róisín, how are you doing?

I'm doing good, thanks. it's been quite a hectic day. I just got back to my flat and I fully crashed, fell asleep. I'm working on a project with The Anthology Film Archives in New York. It’s a really exciting project. Pre- Lebanese Civil War cinema, which isn’t mainstream. There’s no archive, basically. I'm working with a critic and we're trying to make the archives. That's a fun research-led project. but yeah, so that, so I just had that, so I just came up with that. How are you, how was your day?

Where are you right now? Are you in London?

Yeah, I'm in London.

Which area are you in?

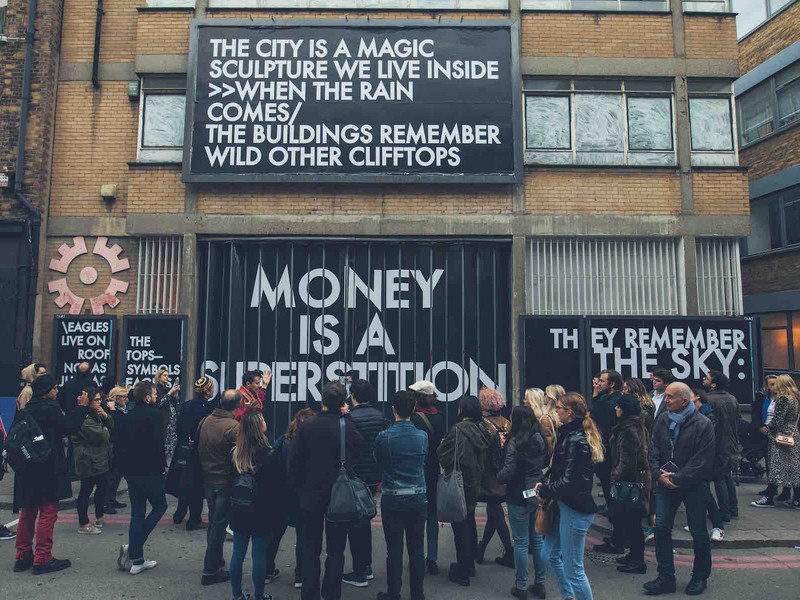

I'm in East London and I've always kind of lived in East London when I've been in England. it's very nice.

All of my family is completely displaced, I grew up in a million different places, constantly moving. I'm still living out a suitcase, but this is officially my home and yeah, I very much like it here. It suits me and I have my friends and everything.

I want to get right into the Habibi Collective. What is The Collective to you?

It’s not a business or anything and it's very much based on my motivation. It’s a grassroots initiative, a community-led project. It’s a resource. An open-access site, that's the weird thing about it. It doesn't exist solely in academia, where a lot of my research lies, but also it's not completely divorced from critical inquiry. So it's operating in this weird ground. It's also very much now operating outside of institutional spaces which was a conscious decision I made in the past year or so. If you had to have a geographical map of the arts, cultural film scene, I don't know where it would lie. Yeah. I don't feel like I can explain what it means to me without being able to place where it is for other people.

How did it come about?

It started in 2018, but my research started way, way before that. I grew up primarily in Ireland in the middle of nowhere. I watched a lot of films. I'd watch a director a night. so I would watch a lot of like, John Casavetes I loved, I loved Harun Farocki, I loved Cheryl Dunye, I loved Trinh T. Minh-ha, a lot of essay films. I'd watch a director and night by the stove.

This was very much at the time when I didn't have any cinemas near me. I wasn't in a city, but it was social media platforms started to become a thing. A lot of what I was discovering was online. It’s not like there’s much of a diaspora, apart from my family, in Ireland. Everything I found was on me. I started making a film log, which I still keep to this day, a chaotic 2003 Microsoft document.

I saw that there was a lack of films by Arab women. And that was a huge part of my identity that I wasn't seeing represented on screen. So, my practice is, and always will be, and has been research-led. So I started researching, and I remember watching Measures of Distance by Mona Hatoum. She’s a Palestinian-Lebanese visual artist who studied in London. It's an essay film about her mom, a correspondence. It's very beautiful. That was a huge turning point for me.

I started from that, from that moment on, actively searching for films by Arab women. There was nothing natural about my finding these films. They weren't available to me. Arab women's film especially is very prominent right now. It's very famous. When you think of big films from the region, you think of Haifaa al-Mansour, Nadine Labaki, Shahad Ameen, Charien Dabis, you think of women! But it was not like that at the time.

A lot of people in interviews ask me, “Why are you focusing on women films when programming seems pretty equal now?” My programs, the non-Habibi ones, are always fifty percent men, fifty percent women, or like more women, but there's nothing natural about that. I get sent 98 percent of films by men. And then I have to do that hard research to find women and then somehow make the program equal. So there’s nothing natural about this growth in women filmmaking. It has been the result of a lot of people working hard behind the scenes.

Again, the same premise of people thinks that the most famous films are the best. Which is so not the case. They’re the most famous because they have the most money and they have the best producer and they have the working distributor.

And so I started Habibi, on Instagram, for a few reasons. I was interested academically, in the archive and in an open-access site. I think accessibility has always been at the heart of what I do. Instagram is super accessible. You don’t need a JSTOR password to access it. So I started posting stills from films that I was watching. Now, I usually get some sent to me or I can reach out to other curators. There's no business plan or anything. It's a community that just grew. None of the people that engage with the Habibi Collective are there because they love film. They’re not film buffs. They're there because of representational purposes because they're seeing themselves represented on screen.

So a lot of people started asking, ‘Where can we watch this work?’ They still ask me that every single day and it fucking drives me mad, but that's how I started curating screenings because, I was like, ‘Okay, people want to see these films. I want to see these films.’ So every screening has been sold out to date and they've kind of been everywhere in the world or wherever I'm invited. And I curate around themes. Climate migration. Queer identity. I don’t like to curate around national borders because borders are so precarious in the region and also that's so homogenizing. We never see a festival around ‘American cinema,’ so why should we have one in Lebanese cinema? Though, I have curated in that vein when I have a mission, like a fundraiser. So for example, I did a Sudanese experimental film festival in Sweden to raise funds for the revolution when it was happening. And also I recently did the Beirut artists festival. And of course, the Independent Iraqi Film Festival. And the screenings I do are always free. They’re always after work hours and always attended, which I think is a really strong accomplishment in London. The audiences are young diasporic people of color, people who work in the arts. They're not the white, neoliberal people that are managing the arts in London.

Left — Serheldan (2003), dir. Serheldan Ahmad and Christine Chamas

Top right — Mussolini's Sister (2018), dir. Juna Suleiman

Bottom right — The Three Disappearances of Soad Hosni (2011), Rania Stephan

Wow, that is such a huge accomplishment.

Yeah, I'm pretty proud of that. I think that's what I'm most proud of. For Habibi Collective, even now that it’s getting more popular, the people that it’s made for are the people that are consuming it. Maybe because I'm a very shrewd businesswoman. I have my very strict politics of production. I'm very strict with how I run things and that has helped me keep control. It hasn't been swept up by brands.

What is your relationship with the films that you deciding? I read something you said in an interview, a film archivist is the part of the film industry that isn't appreciated but they're doing the most work. And I wanted to know what is your actual mentality behind choosing a film and how do you engage with the politics of the films you choose?

Well, there’s a lot to say about politics. The people that I admire in the industry are, first and foremost, P.K. Nair, who was an Indian film archivist, and also kind of Henri Langlois, who was a film archivist in Paris. We don't have an equivalent in the region. In London we have the BFI, in New York, we have the Anthology Film Archives. In the region, I get friends sending me all the time film reels that they've saved from the garbage. And with the heat, people don't know how to preserve these reels. Everyone wants to be a filmmaker. Yet, there’s so much work to be done. So much work. And there's a huge lack of people willing to do that work. So I guess I'm just trying to inspire other people to do similar things.

As for the politics of how I choose films, when I started getting commissions it was from London-based white institutions. And then I realized the program's presence in their public program was just to tick those diversity boxes that would get them more funding that I should have been getting. I've always rejected them because they're fine showing a Black artist, but they're not willing to represent that diversity in their boards or in their staff. So a lot of what I do is working beyond the politics of representation and towards the politics of production.

And by that, I mean supporting the filmmakers beyond just screening their films. And, I'm a moving, breathing film. So I will link people up with suitable people like scriptwriters, producers, or I'll help submit their films to festivals or I'll offer advice or give talks. It’s kind of like a directory. I feel like a feel directory. I come across people like that. And then that's how I gain exposure to their work. And then I work with their film. So that's how I find films. The whole project came out of a lack of resources. There’s no online directory where you can search for an Iraqi film on the revolution in Tahrir Square. Everything I receive is from contacts, from people in the film industry who I know and hear.

I'm a bit bored of institutional critique. I used to think that my presence in these spaces would help diversify them, but it doesn't. I like to work in my own kind of space. I have quite a lot of freedom within how I program the films. For example, I directed the Queer MENA Film Festival and that was something that I never would have been able to do in collaboration with an institution in the region. And even distribution is very political. So, distributors, especially now that we've all moved online, have to do this thing called geo-blocking. Neighboring countries who they don't like don't get to see the films.

I was looking into the Independent Iraqi Film Festival, and I wanted to know what that whole experience was like and the reception of it. I read too somewhere that you were talking about how doing it online and independently from an institution in the region saves you the trouble of going through the politics, but how was the actual process of the festival, and did it start online or did it move into that with the pandemic?

I don't particularly like film festivals. They're very, very cold. They’re culturally gatekeeping. They're very exclusive. With Cannes, the biggest independent film festival in the world, they didn't even show it online and it's just that kind of behavior.

So it was built on being creative and finding a new way that film festivals can be run. I was working with three really incredible, amazing people, Israa Al-Kamali, Shahnaz Dulaimy, and Ahmed Habib, all Iraqis. I was directing and doing the programming mainly. We decided, well, I kind of put forward that we don't charge. If you're a filmmaker applying for a film festival, you need to pay an entry fee, usually quite an extortionate one. You need to have a certified producer and you need to have a European distributor among many other things. So we scrapped all of that. Anyone who wants to apply can apply. And also, we were going to pay you as well. We're going to pay your screening fees. And we eliminated the competition element because that's something I really hate. If we wanted to mobilize filmmakers and create an industry, create community, I'm not going to pit them against each other.

We made it open internationally to anyone for free. Obviously no money in it at all. Zero. We didn't apply for any funding. And, it was online because it could reach more people, and also, none of us are living in Iraq. There’s a huge diaspora and the diaspora is very, very strong. I don’t think there’s any other SWANA community that compares. I guess because of the war.

So yeah, that's why we wanted to make it online so most Iraqis could access it. We also had everything in Arabic and English. and I think that's a big part of how we managed to get the huge Iraqi viewership, which is, again, the thing I'm most proud of. We managed to get our biggest viewers were Iraqis in Iraq.

Wow.

As for selecting the films, I watched over eighty films, and they were all very lo-fi, handhelds, all of this documentary, some really beautiful ones. We showed, obviously the ones that were of the highest quality. The women filmmakers were actually really difficult to find for Iraqi cinema. All of the women filmmakers, apart from Zahraa Ghandour, were a part of the diaspora. I think it's maybe because Iraq is a war zone. It’s very easy to ask, ‘Why aren’t there more Iraqi filmmakers?’ You have to respect that. People can’t just do that. It’s not safe.

We're going to have it next year as well. and we might have it. We'd like to have in real life. It will be very, very easy to have it in London, but I'm more interested to have it in Iraq. Although, I don't think the Iraqi government likes me much. I just don't think it will be a good idea or safe.

So you’re starting a streaming service, Shasha.

Yeah! So Shaha is Arabic for 'Screen.' That’s taking up all of my time right now. It’s a huge operation. There's a lot of us. I’ve always run Habibi Collective, I'm the only person involved. I didn't have money to pay a salary and free labor is one of the worst crimes in the art industry. So that was always my reasoning behind that. It’s just me on my phone. But, obviously, I need a lot of people to make a streaming service, so a huge web development team, UI designers, UX designers, graphic designers, brand identity people, programming, team marketing, blah, blah, blah.

So I made it separate from Habibi because we’re going to show films by men. Habibi's women and women-identifying folk, but Shasha is going to be everyone. And also it's a business, it's a streaming service, there's money, there are transactions. Habibi, I want it to stay beautiful, pure. Me on my phone.

It’ll be ready in January. It's the first independent streaming service for SWANA film, which is very exciting. It’s going to be like 20 films per month.

Left — 3eib (2020), dir. Sarah Bahbah

Top right — Be Like Others (2008), dir. Tanaz Eshaghian

Bottom right — Leila and the Wolves (1984), dir. Heinry Srour

Wow, really?

It’s not going to be a normal service. It’s going to be curated each month. I'm really excited. It probably wouldn't have happened without COVID because I was so busy with screenings. So many work trips planned, which all got canceled. I panicked. But now there is a higher demand for online screenings and also it just reaches more people. You can reach anyone in the world. so I guess it fits in with that whole digital foundation that Habibi was.

I wanted to know, too, about your online magazine ART WORK Magazine.

My first job was as a journalist. And this was at a time when fashion bloggers were a thing. I was writing about fashion stuff, then I lost interest in fashion, although I was a model and I was in the fashion industry again, but from a different position. And then I started becoming interested in art and my academic background is in comparative literature.

So, I never studied film or art. I've always studied literature. I started writing for the magazines I was reading. And also, I have a huge love for academic journals. When I first moved to the UK, South London, I remember being in the big Tesco's and seeing a copy of Vogue, which I had never seen before, and I was like, ‘Mum, can I, can I have this?’ And she was like, ‘What do you want that for?’ My family isn’t even remotely interested in the arts.

You don’t have to explain that one to me. Well acquainted with the attitude.

I was just very attracted to that world. I was working my first full time, journalist position at an Arab youth culture magazine, and I was freelancing at i-D and The Guardian.

And then, just like with film, I didn't really like how things were being run. I had all of these problems and I wanted to create a magazine that was completely moved away from that. Just have friends and people I admire write for it, cultural workers living on the margins. It's very chill. I don't want to try to make something big. We'll have the magazine, not stress about it. No bullshit.

It was a very slow process as well. In journalism, you have to file in like two days, whereas I literally worked on these texts for months with the writers and we'd meet up over coffee and stuff. When I’m freelancing, I never meet the people that I actually write for. So we built those relationships. It was collaborative. There was no hierarchy. And they were present through all of the editing. It was not about the actual output, but more about the process. I never really care about the outcome. The value for me is in the process.

Others of us would like to do the work that you're doing, not specifically archival film work, but more spotting holes in academia or ephemera within the region or about the region. Do you have any advice on how to get up and do the work to inform on the region?

I think the number one main thing is to do your research. I didn't, in no way shape, or form, start any of this being like, ‘I want to change something. I want to change the industry.’ I was just pursuing my interests. And I think that's the number one thing. When people ask, ‘How do I change things?’ You need to, first of all, know everything that you can know about film. You do the work first. I work with so many big institutions where the film team doesn’t know about film. People get into these high positions but it’s not because they know shit, most of the time. It’s about connections.

So, value that interest. And if people do have that one thing that they know a lot about and love, then go for it. Pursue whatever you want to change. You don't need a lot of money. You don't need loads of followers. That will come naturally if you are really persistent with what you want to do.

What I try to do is be really honest and transparent about money. And be open with your contacts, too. People are so weird about sharing their contacts. Share your contacts with everyone. That’s so important. Especially as a journalist. I’m always sharing. I have a database of about 300 press contacts which I share all the time so that other people can pursue careers in journalism, to pitch.

Don’t worry about making change, becoming activists, worry about actually doing your research and doing your hard work, and staying up all night, reading about whatever you're interested in. I think that's key, knowledge. Knowledge is power.