Malice K on Never Trying "Just Enough"

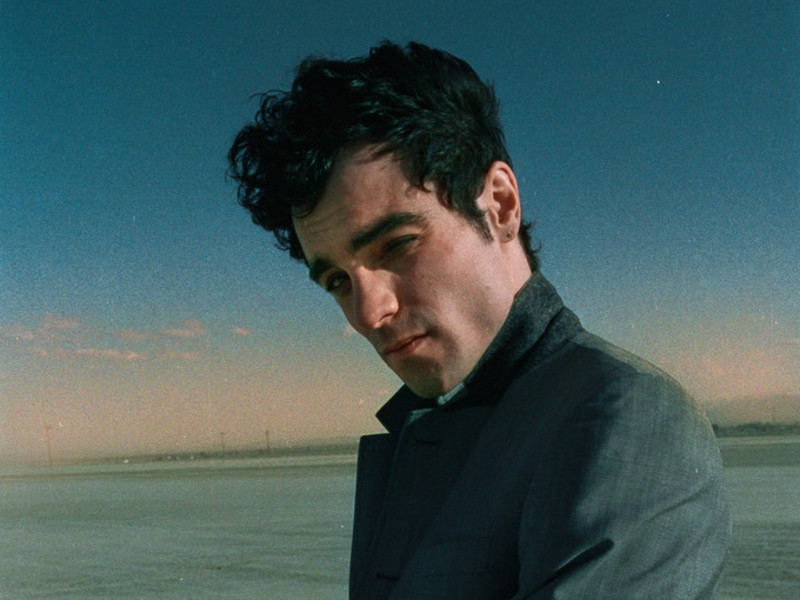

His latest release, “Radio,” is sung like a confession, and compared to the rest of his discography, it’s pretty stripped down. With lyrics like “Almost seven days away from one week sober,” and “I never needed you, please come over,” “Radio” is his most vulnerable song to date — and maybe not all we'll be seeing of him in the near future. We sat down with Malice K to talk about Vegas, furries, and how much he likes doing interviews.

The first time I speak to Alex, he asks if I’m from New York, and I’m a bit of an asshole so I make him guess. He guesses Canada, and I ask if there’s anything about me that feels particularly Canadian. He says it was one guess that was as good as any. I tell him I’m from Ohio.

Alexander Konschuh— I like Ohio — you guys all eat white bread, it’s great.

office— And you’re from Olympia? How’s that? Did that have any impact on how you make music?

Definitely. There’s a lot of music history and culture from there, but you can’t really build a career as a musician there. I mean, you can be a musician and figure it out, but it’s not like New York, where there are a lot of investors or labels or music venues where you can play and make your own way. When I was growing up, I was just around a lot of people who liked to play, and they were just obsessed with music because they were musicians.

But there wasn’t anybody that had an alter ego or stage name or anything. It was all pretty laid back. And that was pretty lame. It took me a long time to feel comfortable pursuing a musical career and having an alter ego and stuff, because growing up, it was pretty shunned. Everyone would be like, “I just play, man” [laughs] But I got a lot of time to just learn and appreciate music, playing without having any aspirations of it becoming something. I think a lot of people will move to New York or LA with this aspiration of becoming this musician-person. And they start there rather than just figuring out how they play.

I read Carrie Brownstein’s biography, and she was talking about Olympia being the place to be for musicians, but she was also a different type of musician than you.

And that was a couple of generations back for me. But it’s true, in a sense. I got the leftovers from that era — a lot of house shows and house venues, but no bar venues or anything, just different houses all over Olympia. And so many bands loved coming through Olympia because they’d get to play these really fun house shows. Being a musician, it’s a good place to be, but trying to make money or have a career as a musician, that’s a different story.

How’d you come up with “Malice K?”

I was a teenager doing some traveling with some friends and we were in Arizona or somewhere in the desert. And everybody was giving each other nicknames, but nobody game me one [laughs] So I had to just pick my own. I was wearing this poncho the whole time — it was the only outfit I wore that whole trip. And my last name is Konschuh, which kind of rhymes with “poncho,” and Alex sort of rhymes with “malice,” so I was Malice Poncho for a while. There was a weird couple-year period where everyone just called me Poncho because of that. But when I decided to put out music, I just changed the poncho part to “K.”

What brought you to the desert?

I wasn’t really going to high school anymore, so it was just something to do. All of my friends were driving down there, they had a roommate that ran away, and they were going to retrieve her from Las Vegas, so I went and it was really fun. She actually didn’t want to come back, but I got some good partying in — tried the slot machine, won like, five cents [laughs]

We had to ask for gas the whole way there, because nobody had any money. We had to go and ask people for five bucks or gas, I didn’t know it was going to be like that at all. But my friends picked me and this other guy’s girlfriend to be a pretend couple, because I was the most trustworthy, or we were the least disarming or least scary-looking. I think they thought, if we were the ones asking, it wouldn’t be an immediate “no.” Maybe they had an eye for those things, because we did make it to Vegas.

Did you have a musical upbringing?

Yeah, my parents were always really interested in music. They cared about it a lot. And I was kind of surprised — my parents were pretty well-educated, but they were teenage parents and stuff, and their backgrounds made it a really cool and rare thing. I had such cool and knowledgeable parents, they always had art books and biographies everywhere, and this huge box of CDs that I would go through and listen to.

They really liked the music that I liked. Growing up with young parents, we’d all be listening to the same music in the car, and they’d be into it. So I was always around music and being influenced by it. And I started playing drums when I was in elementary school, and I’d play at my talent shows or whatever — just solo drums. And then, there was this jazz bar that did open mic nights where we’d go and play. But everything else that I know how to play now, I just kind of taught myself throughout the years. And then one day it all just came together, and I was like, “Well, I should start making songs.”

That’s how it happens. What made you come to New York?

I got a phone call from this record label out here, they were inviting me to try them out, see what they’re about. And I was living in LA before I came here, doing music stuff with this group called Death Proof Inc., which was this artist collective down there. I started the Malice K thing over there. I was building it and then it just got some label attention over here. I’d lost my place in LA while I was visiting Washington but I got a phone call to come visit New York. So I just came out here and figured out how to stay and make it work. And here I am.

When was this?

Recent — around two and a half years ago. I came right when things were opening up again. It was fucking insane [laughs] Every day was like a movie, the most psychotic movie you’ve ever seen. Everybody was out. It felt like the sixties or something. Everyone had kind of acclimated to this life of not working and getting money and drinking every day. So when everyone came out, that’s all you were doing. It was just one big party for months. It was a great time to move.

So “Radio,” your newest single. Break it down for me.

Break it down? It’s a song, and I wrote it, and it’s about feeling hopelessly yourself, and that there’s nothing you can do about it. I assume this is normal for other people, but in my life, I feel that I’m always trying to become something better, or be a better version of myself all the time. And sometimes that’s not necessarily a good thing, and that the things that are your problems are a big part of who you are. Sometimes, wishing that you were better, wanting to be different in a way, it’s kind of not honoring how strange or particular you are as a person.

It’s like, you are yourself, even if that conception of you includes parts you might not like, at least in this present moment. Or am I misinterpreting it?

No, that’s a fair interpretation for sure. When I first came here, and when I first started having fans or people who were looking at me in a certain light, I did a lot of stupid shit. I’d do a show or something, and then I’d just hang out with everyone that came to see the show and get super involved, but it became this whole thing. Being admired, or having to be too familiar with someone too quickly — there was always something about the whole ordeal that made me kind of sick. But I would ignore it because I figured I just needed to get better at that, and that I just needed to learn to enjoy having fans because I’m so lucky to have something like that. And I didn’t realize that I was kind of disrespecting myself, because there’s really no need to try and put myself into that box. That’s what the song’s about — the discomfort that comes with trying to overextend yourself or trying to be outside your comfort zone.

That makes sense. I don’t think we have time to get into parasocial relationships, but people treat you differently. Do you think that separating Malice K from Alex helps you deal with those weird attachments?

I don’t know. I’ve taken a lot of personal distance away from things. I’m trying to create a healthy relationship between what I’m doing and how I’m doing it. Before, I was trying to be at all the parties, trying to have a physical presence and be a full-time performer. And it would work, in terms of people’s engagement or getting attention and stuff like that. But then my work ethic and stuff fell with that, because I couldn’t keep up with going out all the time while also exploring myself and being present with where I’m at in my life. But, as soon as I stepped away from doing that, I saw a huge drop in engagement. And that kind of hurt me a bit, but I’m getting over it.

I’m just not taking all these pictures anymore, and I’m not going out to this party or whatever, so I don’t really have anything to say or post, except for if I drew a picture or if I’m working on a song. I just stopped posting that often. I didn’t post for like, a month, and in that time, my monthly listeners on Spotify dropped by more than half. It dropped forty-something thousand people, who all just stopped listening to what I was doing because I wasn’t keeping my social media presence.

It’s scary how much the Instagram algorithm works, and how the people who are listening to your stuff have to be reminded that you exist.

It’s coming at us so fast.

And there’s a new singer-songwriter every ten minutes.

And Instagram just expects you to compete, which is insane, because it’s not even a music platform. It’s not a platform for anything, it’s just everything at the same time. I just don’t have enough to say for you to think about me in the midst of the million other things happening. And I don’t want to be like, “Oh, I’m eating this” or “I’m doing this” or whatever. Because my Instagram is my portfolio — it’s my website, basically. It’s for what I’ve done and what’s on the way.

If I don’t have anything to say, why would I say something? It feels kind of insane. It’s almost impossible. I’m getting to a point where whatever happens, happens, I guess.

And that’s a healthy distance to maintain because social media is unpredictable.

And they totally censor you. It’s not even a demographic platform — you can’t even consent to what you engage with at all. I’ll post a drawing or something on my story and it’ll get maybe 200 views. And I’m just like, “I’m gonna try something,” and I post a selfie and it gets 2000 views. And I’m just like, “Yo, you just censored my artwork because it didn’t match this algorithmically detected aesthetic that will keep people on the app longer or make them feel a certain way.” What am I going to do? Become an Instagram influencer / model / music, which will definitely jeopardize the other thing that I’m doing? So it’s just like, if you know about me, you know about me and what the fuck ever, it’s not my goddamn problem.

That’s a good way to look at it, because so many people get annoying about trying to establish themselves. Which is fine if that’s the game you wanna play, but a lot of people put themselves in compromising positions just to get clouted.

I’m just trying to invest in my actual future, like Weezer — that’s a band that I would still see. There’s something about them. They just maintained a certain aura about them, like the Pixies. I just think the things you say “no” to are a way bigger investment in the future than just saying “yes” to the demand of the time that you live in. Because someone could be like, “Oh, there’s that really awesome dude. He painted all that stuff, it was really cool.” Or, they could be like, “Oh wait, that’s the guy that’s — I don’t know — the face of Honda” [laughs] Maybe saying “no” to that one thing oculd be a really big investment in your future that’ll end with a napkin you drew on getting into a museum because you didn’t make yourself look like an idiot in a Honda commercial.

Is this you trying to ask for a Honda sponsorship?

I wouldn’t even finish the email, I’d just say yes immediately [laughs]

I’ll pull some strings, send the director of Honda a magazine maybe.

What have you been into lately?

What have I been into? Doing interviews [laughs] I’m just thinking, “Where have I even been? What is there going on?” I’ve just been really into doing interviews, they’re fun. And it’s been feeling good for me to do, because I’m at a point now where I’m just saying things how I would say normally, instead of saying things how I think a musician would say. You know what I mean? I think I have less of an identity wrapped up in what it means to be an artist or a musician. When I first started doing interviews, I’d be nervous, because I’d be thinking, “What if I don’t come across as a musician?” — all this weird existential stuff. But now, I’m at a more comfortable place in my artistic career to where I’m letting go of things like that. And it feels good to talk about myself and be more transparent, more sincere.

I get that, because for a lot of musicians, they have this persona they put out, and if they were all to do interviews as that persona and not let people see their actual selves, it would get really boring, because we wouldn’t be getting anything that we didn’t already see. You know what I mean?

Totally. And there’s a lot of musicians and a lot of things that I’ve felt really loyal to. And I was really enamored with them before coming here and doing what I’ve been doing. But now, I guess I realize how much business sense you have to have. A lot of these artists that I’ve admired, I’ve realized that they made a lot of business decisions and weren’t total psychos, which is so much of the persona of the artist — that’s the way to sell it, because it’s a business made off of the image of this one person that goes to publications or whatever. And I started seeing that once I started treating music more like a job. Once I stopped romanticizing this idea of the artist, felt like it freed me up to do things the way I’m doing them instead of thinking of music like, “Oh, I’m entering this atmosphere,” or “I’m among these types of people.” I’m just alone and desperate and I don’t know what the fuck’s going on [laughs] I’m just trying to be here another year and I’m just making it work.

What's your writing process?

I’ll have a guitar part that I really like, and then I’ll just mumble whatever until I figure out the cadence I want the song to be in, and then I’ll figure out the melody and I’ll just fuck around with it and sometimes somethimgng will happen immediately. But for a lot of the songs I write, if I don’t write it in ten, maybe twenty minutes max, it usually won’t be a good song. Every time I pick up a guitar to play, I’m just trying to find the moment where that happens.

Because when I’m being honest and in a regular conversation, I’m not thinking about what I’m going to say, I’m just talking. And I think it’s music or art that does the same thing, that doesn’t happen often, but where you can just say whatever and have it fit and match the parameters of the melody and the structure of the wording that you want to use. It’s all about doing that every day until something happens, and then knowing when to move on so you don’t get bored.

I have a shit ton of different songs or half songs or quarter songs, or these riffs that I’ll just shuffle through. I’ll just pick up the guitar and go through everything that I have. And most of the time, nothing happens. Maybe once every couple months, I can be honest with myself and have it match a melody that feels catchy. Because I don’t have a band. It’s just me.

Did “Radio” happen in 10 minutes?

The lyrics did. It happened super fast and felt really good. I felt guilty about how honest I was being with myself, thinking, “I’m not supposed to say that,” [laughs] It was a really good feeling.

You’re a little nervous about putting something out because it feels like you’re naked in it.

Oh, that’s good. Yeah.

I hear you're playing a show in London?

Yeah, anybody can come to London. It’s a free show, zero dollars.

You just have to fly to London

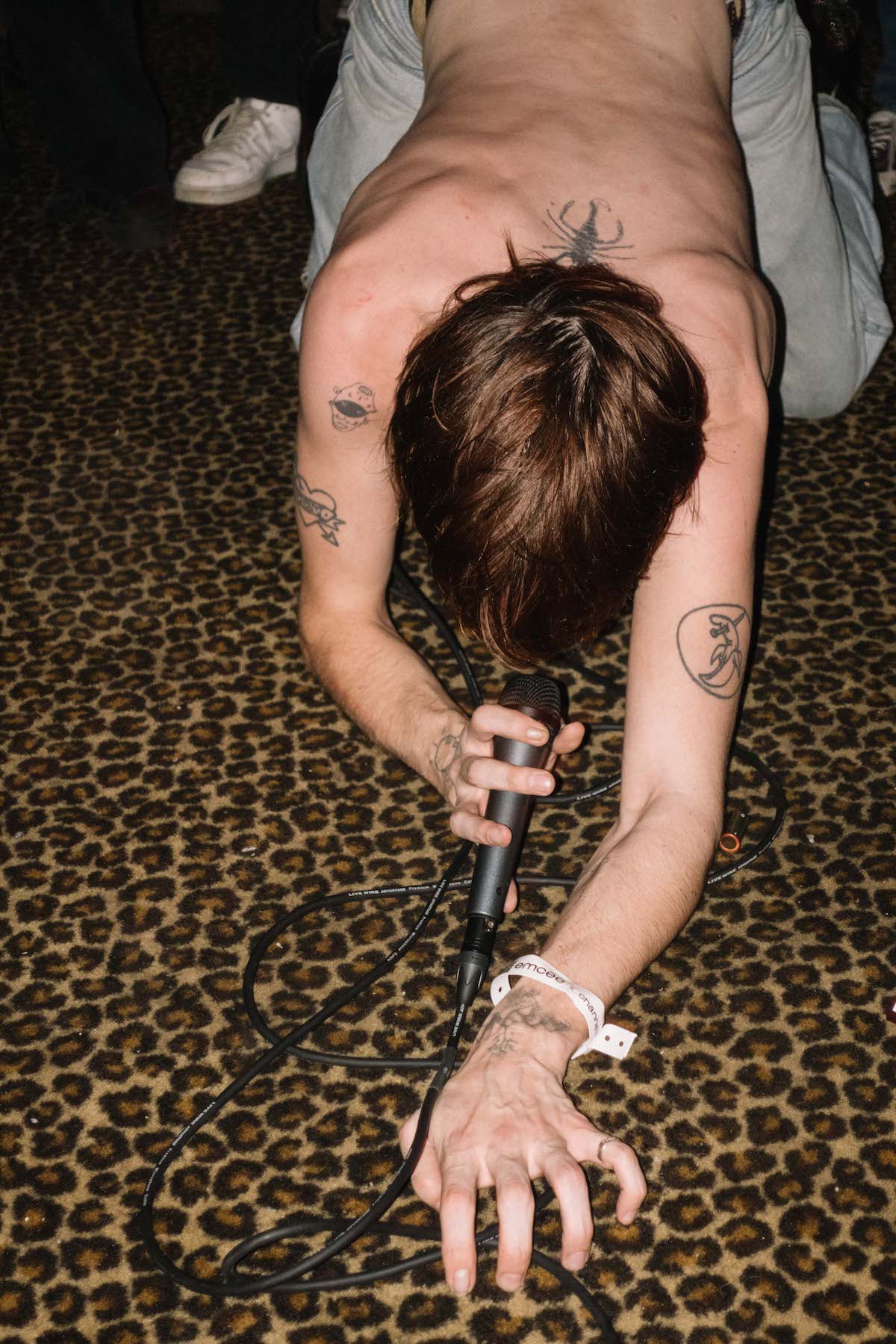

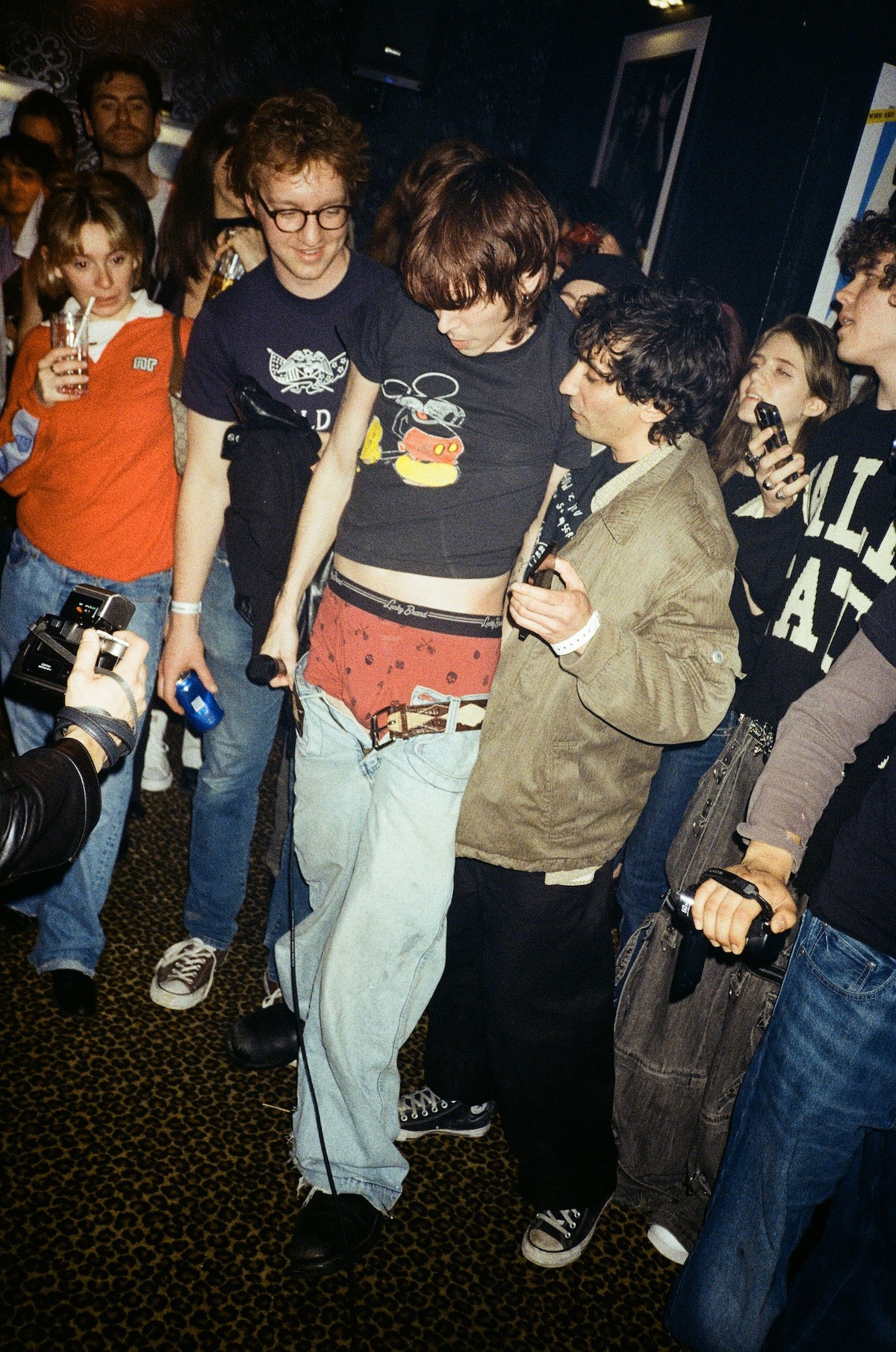

[laughs] Maybe this show is just for all the chaps and lasses. My show at Gonzo's was all-ages, so it was a little reckless. My teenage fans are grazy. They go hard.

Kids go crazy. Have you ever been to Trans Pecos?

Yeah.

Once I went and it ended up being this all-ages furry night. I didn’t even realize it was furry night, it was just called “Club Kitten” so I just thought it was a cute name about cats. And I was like, “Hell yeah, I love cats.” And then people showed up in tails and stuff and there were like, fourteen year-old furries there. You love cats, but they love cats. But was a fun night. The furries know how to party.

You’re like, “I didn’t even know this was what I wanted.” I mean, no judgement. I’m not a furry. If you are, you should go undercover for the magazine.

That’s ok. I am also not a furry. I just like Trans Pecos.

I’m gonna write a cross-article about furries in the workplace or something [laughs] but yeah. I got all these younger fans from when I was doing the Deathproof stuff. It was this modern kind of e-boy thing — a real Lil Peep kind of vibe. But they go super hard. The last time I did a New York show with the Deathproof people, I realized that this is probably where my fans are at, because everyone was singing the lyrics. And I couldn’t get off the stage for like, twenty minutes. I was just signing stuff, and I couldn’t stop signing stuff. People gave me their phones, their inhalers, all this stuff. And I was like, “I guess this is where I’m at now.”

So you’re making the show all-ages because you want more inhalers.

No! I didn’t keep them. I don’t want your inhalers.