Midtown Magic with Dream Baby Press

We open with magic from Noah Levine, who says that tonight, we are all becoming part of “magic’s inner circle.” Meanwhile, I’ve never solved a Rubik’s Cube. He starts, saying, “You can probably tell I was a kid who had a magic kit growing up.” We can. “Did anyone else have a magic kit?” Some people shyly raise their hands. Fire offhandedly comes out of his fingers. Noah makes marbles appear in cups and other fun magical things. After the reading, Vilda and I admit to each other that we were looking for any sleights of hand. We couldn’t find any.

Ruby McCollister opens ranting about how the atomic bomb made men unable to have sex, saying, “The more violence released into the world, the more hysterical men’s penises get, softening like hysterical women in couches.” Bombs are phallic and most militarism is a hegemonically masculine display of power — there has to be some correlation. She then goes on a frenzied analysis of Al Pacino’s natal chart. His Mars in Gemini means he’s a sub. “Most actors are submissives,” she says. “I’d admit to my own submissive tendencies, but instead my aunt died.” We take a break from Al Pacino sex talk to analyze her late Aunt Nancy’s natal chart. Two of Aunt Nancy’s Big Three are Libra. The room groans in solidarity.

Ruby talks about her family affairs and I feel like I shouldn’t be allowed to know anything she reads. Aunt Nancy had an affair that resulted in something vaguely incestuous (not by blood, she just had kids with her brother-in-law). Her grandfather was a descendant of Mormon polygamists and “like a child who’s endlessly at his own cowboy-themed birthday party.” Her father was sued by the IRS for never paying taxes. She half-cynically half-lovingly describes her parents as “cultural dilettantes,” (the same attitude can be transferred to the downtown literary scene), but Nancy gets the debt down from $100,000 to $20,000 before going to work for the IRS. According to Ruby, “Nancy lived normal but in a perverse way.” Don’t we all.

Alex Auder was born in the Chelsea Hotel to superstar Viva. WAP plays as Alex walks up and we can’t stop it. From her memoir, Don’t Call Me Home, she turns to a chapter named “G spot” and reads nostalgically about puberty — she and her friends used to fight over who has more pubes and who has “cherry pits or peach pits for tits.” Bitingly funny, Alex speaks matter-of-factly yet leaves us howling. It takes a certain level of grace and maturity to be able to tell strangers about your most awkward “secret lusts.” We joke that there are no original experiences in girlhood. But once in her youth, Alex and a friend had pretended to be wives on the Western Frontier sleeping with their husbands, straddling Grandma’s horsehair pillows next to each other. A young Alex had called for a stop, shyly asking, “Would we really… do it next to each other on the wagon?” The friend takes a beat before solemnly responding, “We would do whatever it took to survive.” Perhaps there are a few original experiences.

There’s a whole cast of characters — Eastern European neighbors, would-be rockstars, and Alex’s hot math teacher, who she fantasized about mounting in his swivel chair. There was a 16-year-old Esther dating a 20-something-year-old Basquiat. There was a timely allure to age gaps, and Alex says “their coolness blurred their ages.” I’m a 20-something, people say I’m pretty cool, and I’m not dating any 16-year-olds. Vincent Gallo is a recurring character. Reuniting with a high-school aged Alex, he told her, “You’ve grown up so much.” There was a decade between them, so we groan at that. When Alex lost the role in Dangerous Liaisons to Uma Thurman, Vincent had her take off her top “to compare their bodies.” We all groan some more. Her next few misadventures involve trying to sleep with him. Alex believed she had to “pay a penance to use a penis.” She pretended be wowed by his rare guitar collection and freakishly pristine closet. The two sleep together after Viva, following a plastic surgery-related mental breakdown, tells Alex, “Go out tonight,” and in the same breath adds, “Also I might commit suicide.”

Peyton Dix picks “I’m Coming Out” as her walkout song. She starts with a booming, “Heterosexuality!” Someone guffaws. “Exactly,” she says in response. She talks about how gay she is: “Gay like Meg from Hercules” (received with multiple hums of recognition), gay like the monologue from Hereditary (which she and I recite together). She writes about her first male relationship after many years of lesbianism. “Lesbians need a vacation. Dykes need a day off. It’s a lot to be constantly checking in.” She emphasizes these last two words like she’s dated a girl who weaponized therapy speak. “Being a woman who loves women is the hardest thing you can do. It’s actually straight women who need allies, not lesbians.” The room is quiet, but I get it. With a thinly veiled brag about how she once had sex for six hours, she explains how, after multiple heavy relationships, she needed something “easy and simple. And what’s more simple than a man?”

“But,” she starts, leaning on the magic counter, “the thing about good dick — you get crazy.” Another hum of solidarity from the audience. “I’ve seen some of the best minds of my generation go insane over some dude named [redacted].” Here, I audibly screech. Peyton had just named an ex of mine. I’m floored. At this moment, Matt takes a particularly unflattering picture of me. Aside from getting her heart broken by a man, Peyton speaks of her worries: “What does this mean for my identity? Will I lose my pride gigs?” The piece ends when she hears back from her ex in an apology email, regretting how he was “hearing, not listening.” “This man sounds like a lesbian,” she says. We laugh. “I can taste what it feels like to be loved by him.” We stop laughing. Peyton ends with a consideration that she might be bi — “Bi as in Obama. Bi as in that one interracial Bedstuy couple. Bi as in ‘I went to film school.’ Bi as in, ‘It was Emerson College.’”

The Rubin walks out blindfolded. Feeling his way around the counter, he says, “Someone will ask me, ‘Isn’t it easier to do magic without a blindfold?’ to which I’ll say, ‘Who’s talking?’” I make a noise of approval. He (attempts to) point at me, saying, “This guy gets it!” Perfect situational irony. The Rubin materializes a lit joint. Nice. A few tricks later, he turns a paper crane into another lit joint. I think he just wanted to smoke inside, but what’s more magical than that? He throws a bunch of cards into the air and makes a funny performance of supposedly grabbing the wrong card midair, to which he yells, “BEHOLD,” does an impressively high kick, and conjures the correct card. He’s like if Jack Black were a magician.

Mackenzie Thomas is noted to have gotten an 11 on her ACT Superscore. Cheers all around. She shares short diary entries that document everything — from her disgust at Bobby Flay’s face to the time Justin Bieber peed in a janitor’s bucket while saying “Fuck Bill Clinton.” The piece turns into a letter to an (ex?) lover, as she reads, “You texted me and then I got pushed into the intersection while on a Bird scooter. A woman in a t-shirt that said ‘Pugs Not Drugs’ carried me to the pavement.” We learn more about Mackenzie than we ever planned, as she tells us, “The first time I masturbated was to a College Humor skit on workplace dynamics. My first boyfriend never showed me his ballsack because he was afraid I wouldn’t like it. Whenever I sucked his dick, he’d tuck his balls in his underwear.” Not once since she’s started reading have we stopped laughing.

It’s less poetry and more documentation of growing up. Taking us back to elementary school, Mackenzie tells us of a boy who pretended to like her just so he could organize her backpack — “a radical act of love.” I wonder what bell hooks would say. Now, she writes of passing young girls and wondering “if they can tell that I was once young.” People laugh some more. I’m not sure if I can. She finishes realizing her own youth and dependence — from the homeless woman who gave her twenty dollars because she was afraid Mackenzie wasn’t eating enough, to the time she got her eyes dilated and went to the supermarket. “What awoke within me was a primal desire to be illiterate.” She wasn’t sure what was better — getting to ask everyone what things were, or her newfound access to “a helplessness that felt justified.”

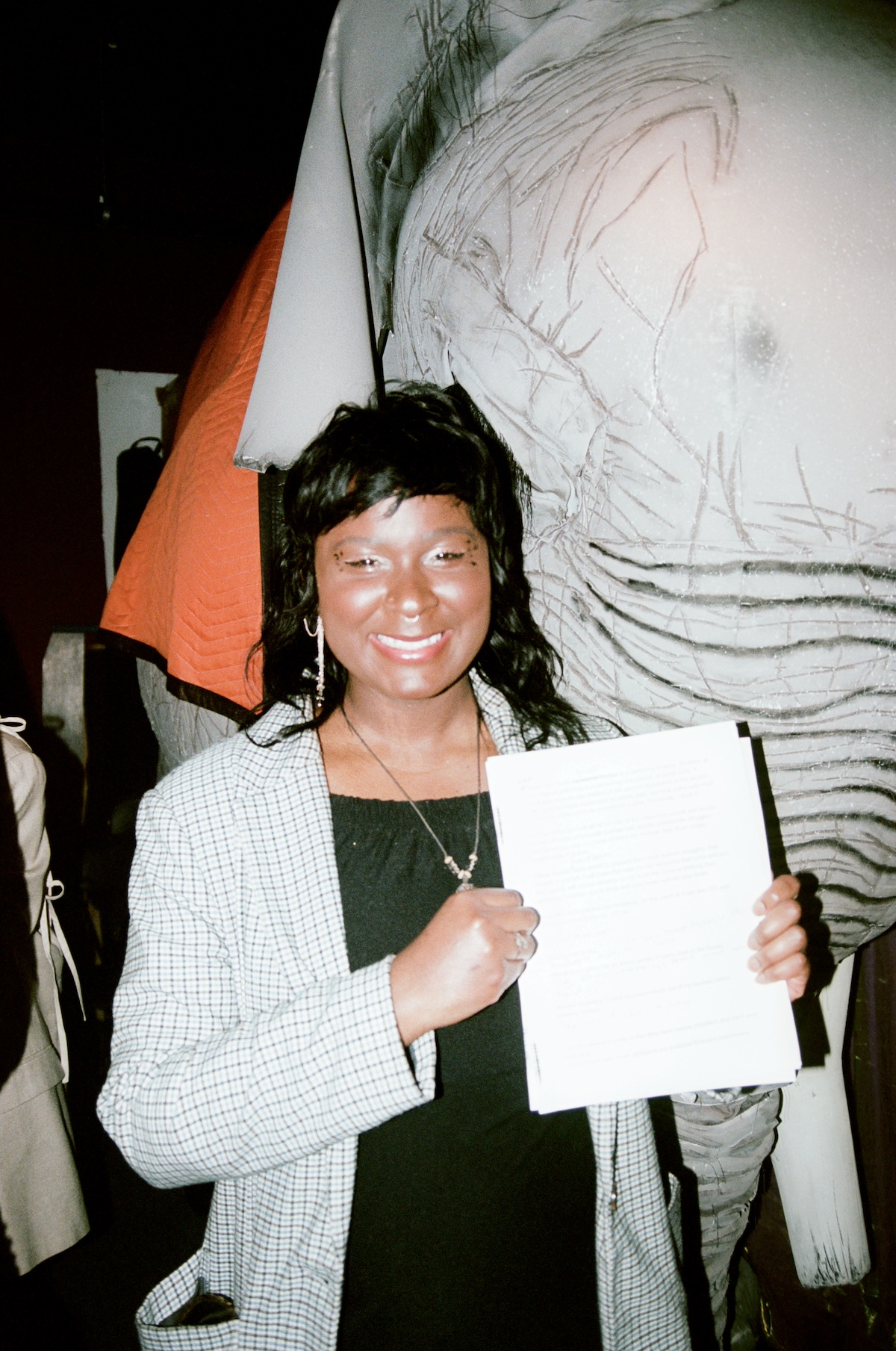

Leah Victoria Hennessey reads what’s been dubbed “homoerotic fanfic.” The Guardian called it “quite literally the end of civilization,” so I have high hopes. Leah shouts out Emily Allan — each piece is a poem Leah had written to Emily during the pandemic. Why? “Because we’re obsessed with each other,” as Emily says. During the pandemic, Leah would only leave her house to mail a poem to Emily. They came to dub themselves as the reincarnations of Lord Byron and Percy Shelley. It was as if they were separated by war (one of them was living in LES, the other on the UWS). It's literally a labor of love, as Emily had edited and made a zine out of every poem Leah had sent her. I want a love like that.

Each piece is short and cute. “What’s poetry?” Leah starts. “Correspondences between poets and the moon. Some genius gets it in his head to talk to the sun.” It’s love letters mixed with cultural commentary and fragmented musings, as Leah reads, “One more tenant of dogma: I love you.” “Being a romantic means cultivating a subordinate relationship to the muse.” The first few pieces are a high-up and airy, but as she continues, she reads quicker — less like someone reading poetry and more like someone realizing something: “What if this is really all we got? That haircut and someone else’s porn, masturbating to my rage for Brett Anderson.” With longing looks shot to Emily and an enveloping toothy smile, Leah drops her zine. If she’s blushing, I can’t tell. “This really is for Emily and Byron,” she adds tenderly. It feels like we’re intruding. “No one in yoga knows what I know,” she says, cheekily. And right before she finishes, she makes direct eye contact with me and says “Don’t tell anyone.”

Ena Da dances out saying, “Under every Elon Musk tweet is a gathering of idiots.” Instantly, I think of how I was blocked by Elon Musk on Instagram for “cyberbullying.” Ena says that we are no longer readers at a reading, but a council of wizards at a magical gathering. We play a game in which Ena has had “mortals from Instagram” submit their curses for consideration, and we — the wizard council — can either choose to lift the curse or let the curse remain. Among the mortals is not, however, Andrew Tate. “No amount of magic can help Andrew Tate,” says Ena. The first curse: “Mid pussy.” “In defense of the curse!” Ena shouts theatrically, “The stars must gleam against the night sky to shine, good pussy must gleam against mid pussy to shine.” That was poetic. Unanimously, we choose to not lift the curse.

One curse is perpetual lateness. Ena says, “We need people to be late and make us feel better about ourselves.” Unanimously, we agree the curse stays. “SUFFER!” yells Ena. Another curse comes from someone “who never has a normal amount of pens in their pocket — either five pens or none at all.” “In defense of this curse,” Ena says, “there is a penis joke in here, should they find it.” The curse stays. The next few curses include too-small earholes, broccoli-induced hiccups, and owners with cats who eat their earwax. Apparently, this last one is pretty common — four people in the room say their cat does the same thing. The last curse comes from someone who sneezes like a dad. In defense of this curse, Ena says it’s “healing for those with daddy issues.” When asked if we would lift this curse, the council yells out a resounding, “NO!”

Ivy Wolk reads a devastating piece about a girl she had feelings for — whether or not they were positive feelings is lost unto me (and Ivy herself, I think). Intimate yet relatable, it’s a piece about that weird intersection of love and hate. “I’m friends with everyone she’s a fan of,” she starts, “But the association doesn’t help if you have a bad personality.” How New York. “She tells me all my friends are just caricatures performing references they know, but then she quotes a book to me and I don’t tell her that she’s doing it too.” Clout will not save you. Your crushes are just as performative as the people around you. And your ex-friend seeing you on Instagram will not make them forgive you. These are all hard-learned lessons.

Ivy despairs rapidly. “She unfollowed me on Twitter because she ‘only wanted to hear about herself in the long-form,'” says Ivy. “But she wouldn’t like anything I had to write.” It’s a conundrum well-known downtown, the urge to self-mythologize and the neurotic curating that follows. Ivy’s piece is about wreckage — lost friends and purged desires. When you are forced to finish loving someone, what do you do with whatever you have left for them? “If she died, no one would tell me,” says Ivy. What do you do with that? Ivy doesn’t seem to know any more than I do. “I say I love her twice a day and I say it out loud. I think I love her because she hates me and we don’t talk anymore.” It’s sickening how much I understand her. “She said she wants to show up on my doorstep addicted to heroin so I can take care of her. I want the same thing. I want to hold her scabby arms and give her clean needles.” Oh my god. “I’m sure she feels normal right now.” Double oh my god.

Ronald Wohlman is described as “overly medicated, not seeing a shrink.” More cheers. He writes playfully, saying “I can’t find one person on the Upper West Side who will share their Ozempic with me, so I have to lose weight with an old-fashioned diet…I was eating three meals a day of nothing.” We laugh, silently wondering if someone needs to check on Ronald. Reading off massive playing cards, he writes of buying a chicken on the way to the gym, of the push and pull between temptation and the things we do to resist them. He eats the chicken on a bench on an island on Broadway. “If you drove past,” he starts, “You’d think, ‘How does New York City turn their middle-aged men into that guy?’” And yet, he licks each finger twice.

Ronald writes about going to the gym after, having shoved the leftovers in his gym bag. But no great hero story is complete without the ultimate confrontation — Ronald left his gym membership card at the bottom of the chicken bag, and the last thing he wants to do is broadcast to the whole gym that he has an entire chicken in his bag. Nevertheless, he persists, and with as much pride as he can muster, reveals the chicken to reach his card. The line of elderly Jews behind him let out a collective gasp — the chicken was not kosher. From his imagined thoughts of the people around him, to his third-person viewing of himself eating chicken on the island on Broadway, Ronald seems to be stuck in the cycle of shame and self-surveillance that we see writers so often engage in. I wonder if they know I'm going to be detailing tonight on my Substack.