Palm Wine Collectors

Every act of photographic portraiture is characterized by an inherent power dynamic between subject and photographer. Ethnographic photography, however, which is historically and to this day produced mainly by Westerners, seems to be characterized by a pronounced imbalance of this dynamic, in which the author assumes complete control of the creation of the image. My father is South African, my mother is American, but we also speak German. Growing up in Namibia, I later came to question my position as an ‘African’ photographer of ‘Western’ descent and found opportunity in navigating the representational politics of photographing African people.

I think my attraction to photographing people lies in photography’s complicated history of representation of the African continent. Its function has shifted from being a tool of oppression during colonialism to becoming a means of empowerment and self-expression. Contemporary African photography aims to establish new narratives and identities, both personal and cultural; my work is often influenced by its past and present uses, as I hope to produce images that drive important dialogue on documentary photography as well as the ethics of representing cultural ‘difference’.

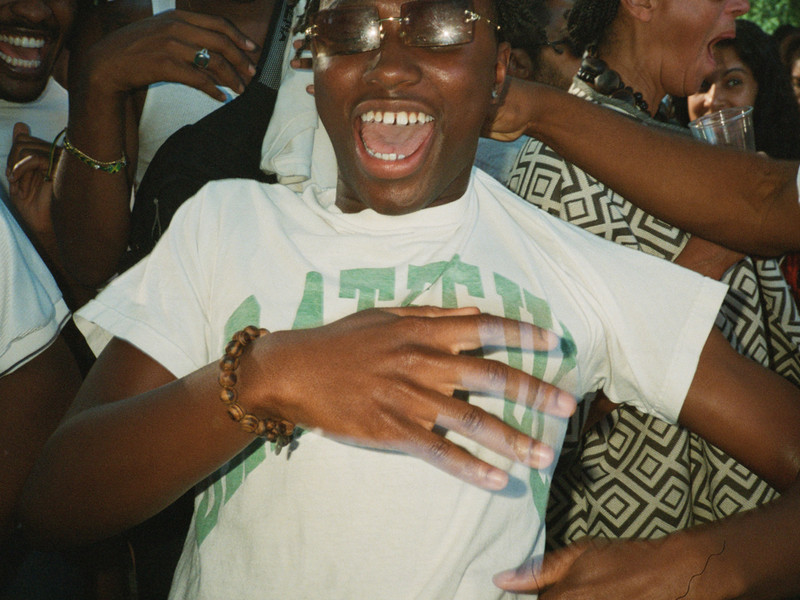

As I became increasingly magnetized to portraiture and gained a clearer understanding of issues surrounding photography and identity, my photographic efforts in Namibia became more directed towards people. I made multiple trips over three years to collaborate with young Himba men on the series entitled Ovahimba Youth Self Portraits. One year later I returned to the area to distribute posters amongst the young men who participated in the project. I’d hoped that it would create a sense of community as they viewed themselves and others all depicted on the printout. It was an unbelievable experience seeing the transformations of so many of the same young men a year later. I began to recognize the culture’s dynamism, particularly in the way that male Himba youth were extending their identities beyond the purely traditional.

While travelling along the Kunene River to hand out the posters, I came across a familiar young man named Wakarerera Tjondu, who in disbelief of seeing me again took me for a celebratory drink of the palm wine called ‘Otusu’. This was the first time I had ever witnessed a Makalani Palm actively being tapped, and by the same young man who in the previous project performed so fiercely for the camera in his Puma jacket. It highlighted the balance that I had already recognized some time ago: that although there clearly is a shift toward modernity, a strong kinship to tradition is sustained. These men understand something about the constructed/fluid nature of personal and cultural identity. I spent the night camping near their settlement, talking to the men about palm wine production and we headed off the following morning to continue my journey to distribute the posters.

At the time, the area was suffering a major drought and many of the Himba had moved to the river's edge for water and the nourishing qualities of ‘Otusu’. On travelling downstream, I found numerous palms being tapped by Himba men and so came to the decision to produce the series of environmental portraits. Having already seen numerous palms being tapped, I had the idea of photographing each scene in a typological, deadpan approach. This way I would standardize the framing of each shot and allow each subject ample space to perform for the camera. My goal was to create images of these men that spoke about their relationship to their surroundings. It’s a very poignant issue considering the government's plan to build a Hydro-Electric Power Station further downstream, which would subsequently flood large areas of ancestral land. Not to forget the ban on the tapping of Palms, which the Himba completely neglect. These images are meant to empower the people depicted within them, highlighting an otherwise unknown facet of their culture, one they take great pride in. My aim was never to reveal the process through photographs; I simply wanted to make detailed images that celebrate these men and this facet of their lives.

The series was completed during two separate trips to the Kunene River, each roughly two weeks in length. I always travelled with a translator; together we were able to freely interact with the men, making it possible for each of them to discuss the production of their portrait and then directing them where needed during the shoot. I’d start by showing them a digital image to give them an idea of my framing and would then switch to my analogue camera to capture the image. Locating palms that were being tapped wasn’t easy either. Usually these trees are hidden from the road, so I spent considerable time exploring the area by foot with the translator to locate more people collecting the wine.

I think returning on several occasions over the years, showing them their pictures, helped me gain these young men's trust in photographing them as they’d like to be seen by an outside audience. I had never seen images of Palm Wine Collectors in Namibia before and these young men invited me to make their portraits – they each received the pictures that were taken of them. I always carried a little printer with me to print out the photographs.