Klára Hosnedlová Time Travels

Your work is an enriched mixture of artistic disciplines: performance, sculpture, painting. How did this hybridization emerge in the first place?

When I started, my very first impulse was to construct exhibitions as sensorial environments for viewers to immerse themselves in. I am greatly influenced by architecture. My first shows were always conceived as site-specific installations, created with the public in mind. I am particularly interested in exploring how to seamlessly integrate artwork into a specific context. I’d say that this investigative process has influenced my own architectural practice. I would create ad-hoc landscapes dependent on, and in relation to, the exhibition space and craft new objects that narrate their own distinct stories.

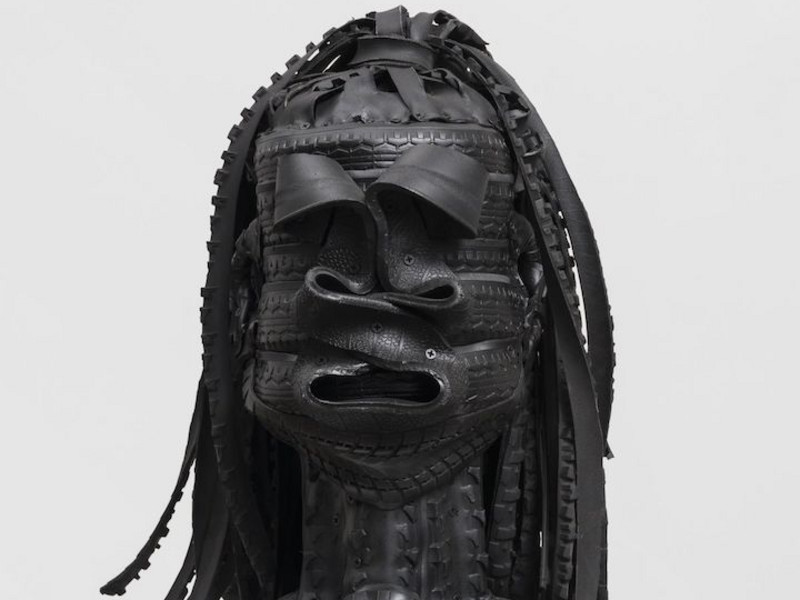

The idea to work with large-scale sculptures began quite organically, as a byproduct of curiosity. Rather than “just” making an artwork, I had an urge to dissect and develop a situation. The objects themselves look like collections of small, torn-off pieces sourced from various landscapes.

I have implemented performance art since the beginning — I also created costumes, adjacent paintings, and embroidery. I guess this approach is similar to Gesamtkunstwerk, each aspect of the practice serves the same absolute creative vision, one where all elements and disciplines resonate with each other.

What about the references that you incorporate? I particularly like the confluence of heritage and futurism.

Cross-generational references have always interested me. Much of my work involves research — including both aged techniques and heritage know-how. I then source the right people who can help me duplicate and integrate these findings into my artistic practice often topped with modern infusions. I like to take inspiration from our collective memory and mix it with fragments from our contemporary reality. I never strive for historical accuracy; I’d rather create something new.

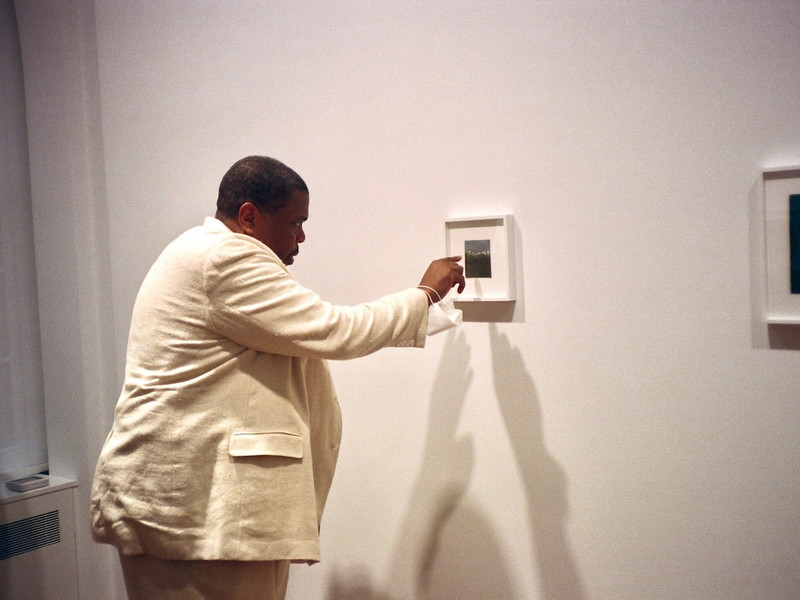

Klára Hosnedlová: Sounds of Hatching, exhibition view, The 16th Lyon Biennale: manifesto of fragility — A World of Endless Promise, LUGDUNUM — Museum & Roman Theaters, 2022.

Photo: Aurélien Mole. Courtesy the artist; Hunt Kastner, Prague and Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin.

You work a lot with embroidery, which I suppose qualifies as a more traditional technique. How did you first get introduced to the craft and why does it interest you?

The first time I worked with embroidery was during my art studies, but I knew about it for a long time before. At the time, especially in art school, embroideries were not really considered an art form per se. People viewed it as a technique only, either used in the textile industry or as a domestic activity, and I quite liked that. I think it has to do with my need for intimacy. This categorization outside of the fine arts framework made me feel comfortable. I never felt any pressure to master the craft. For me, it is a tranquil practice that creates this meditative sphere where I feel free to create.

I’m curious about the visual connection — I read in another feature that your embroidered pieces often are based on photographs. Could you share more about the process?

I would say that the workflow is quite organic. Usually, my embroideries are based on photographs from previous performances. So in most cases, the current exhibition includes references from the one before. I think of it as an endless circle, where all the artworks relate to one another. My work addresses themes of memory and replacement; it fulfills a need to perceive everything from a wider context and make new connections.

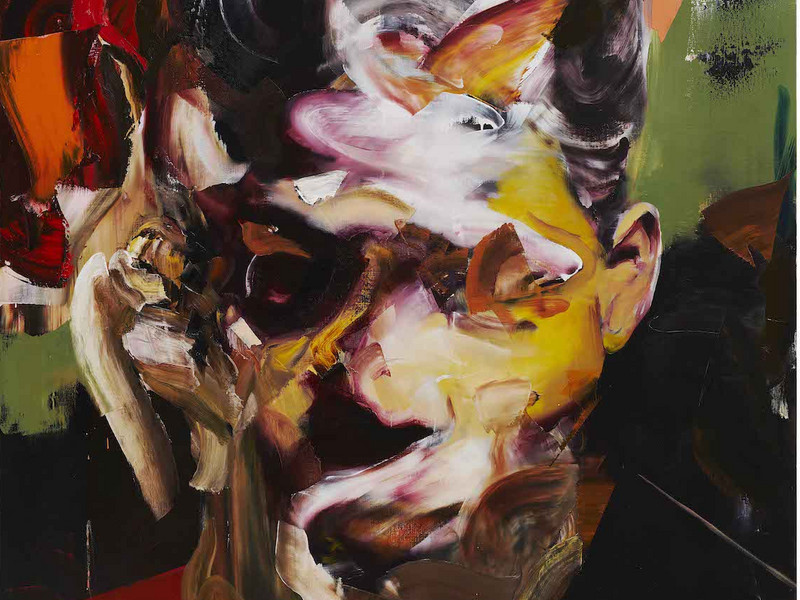

Klára Hosnedlová: To Infinity, exhibition view, Kestner Gesellschaft, Hanover, 2023.

Photo: Zdeněk Porcal - Studio Flusser. Courtesy the artist; Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin and White Cube.

You mentioned performance art before. It’s interesting how each performance targets you and your performers, but also heavily emphasizes the audience and their own involvement.

I think it’s important to explain that my performances are not open to the public. They are always conducted in advance, even before the actual exhibition opening. Once an exhibition opens, each performance is relayed through pre-recorded documentation, usually a mix of photography and video. However, the audience is encouraged to navigate the space in a similar manner as the performers. I want them to walk in the same path, yet bring their own presence and traces to the installation.

For me, the dialogue between performer and environment is as important as the dialogue between audience and environment. I don’t request the installations to be “protected.” Once they are open to the public there are no barriers or limitations. Essentially, you can walk on them if you like. It’s not uncommon for visitors to step on a piece of tapestry or an epoxy puddle as they navigate through the show space. And that is fine. I really value the viewer’s freedom to circulate with full integration in the environment. This is crucial to me. It resonates with the whole idea of exhibition as an experience, to blur the long lasting hierarchy between artwork and scenography.

Your recent exhibition GROWTH at Kunsthalle Basel provided a form of commentary on time, as it linked our past, present, and future society, while it also addressed the fine line between dystopia and utopia. Could you explain how this idea came about?

I rarely develop any personal themes through my work. I’d rather provide a commentary on society based on ordinary details from our everyday lives. Take, for instance, the motifs of the embroideries. They depict situations where a performer manipulates quotidian objects which we’re all familiar with, like smartphones or UV flashlights. By purposefully ignoring the sophistication of these objects, I reduce them to their purest form and empty them from their function. I want to shift the focus back to the human figure. If there is any melancholy attached to these images, it is not meant to play on either dystopia or utopia. It has never been a conscious intent, at least. Actually, I particularly dislike when people label my work as post-apocalyptic. I am more interested in the individuals themselves and the emotions involved when we are confronted with specific aspects of society.

What lies ahead? Any upcoming projects that you can share with us?

Right now, I am preparing a solo show for the Historic Hall of Hamburger Bahnhof, which opens in 2025. I am also preparing an exhibition at White Cube in London.