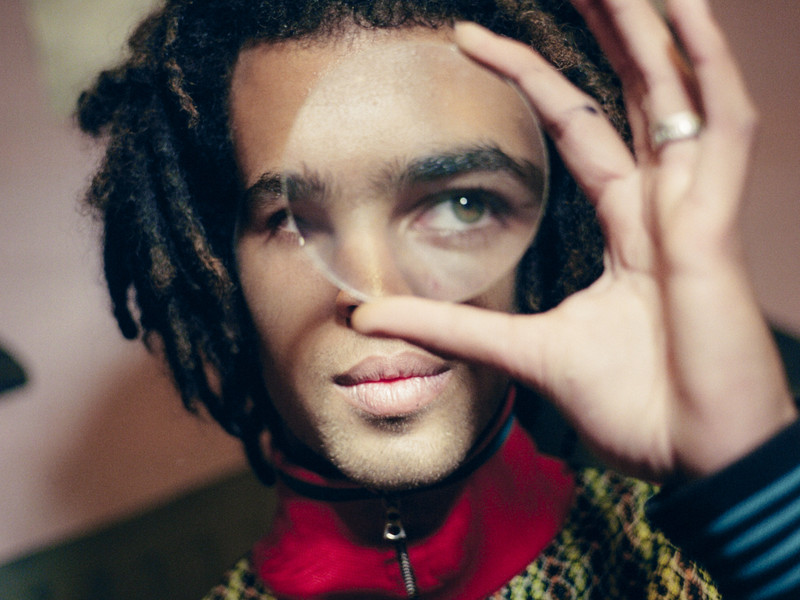

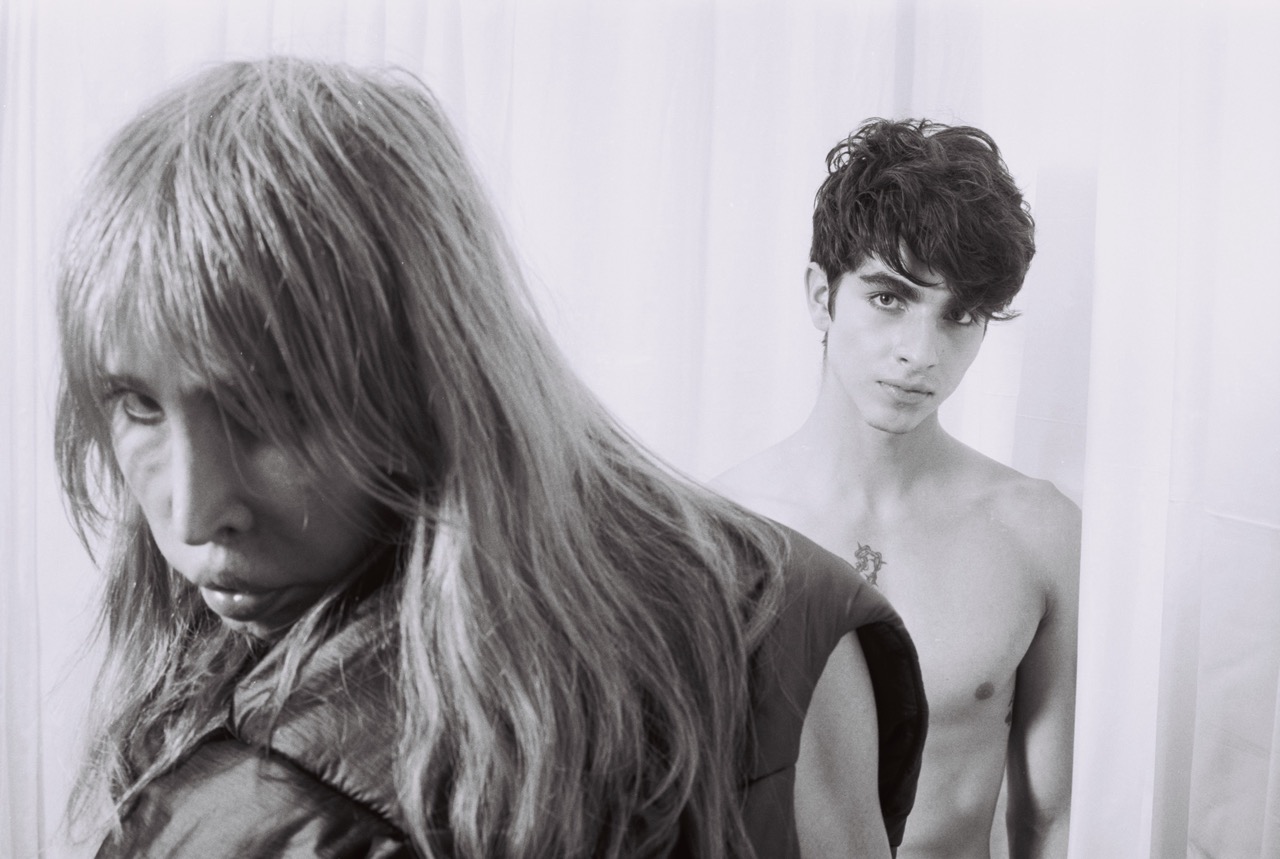

End of the World marks an important return for Shayer. After twelve years at ABT, he left the company and addressed the racial inequalities he experienced as a black dancer in a predominantly white industry. The choreography within this piece mirrors Shayer's own struggles, with the music acting as a reflection of his introspective journey, stepping into a different creative space- one where he reclaims dance on his own terms. "In the case of this piece, I was presented with the music to work with,” says Shayer. “And suddenly I could feel myself coming back, through Zach Tabori’s melancholic tone. It felt like a symbiotic narrative about what I’ve gone through—and that gave meaning to my pursuit of creating a means of expression, a purpose for dancing."

Stay informed on our latest news!