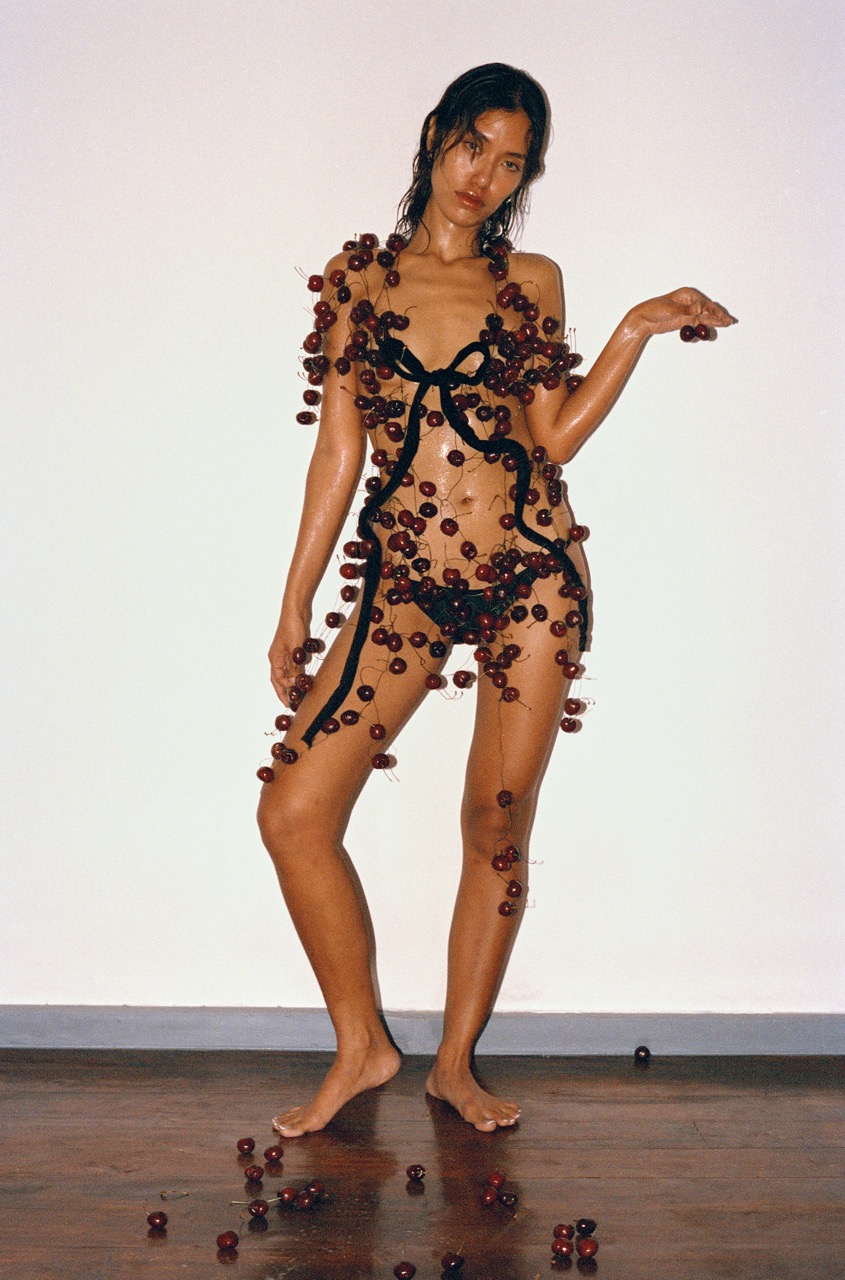

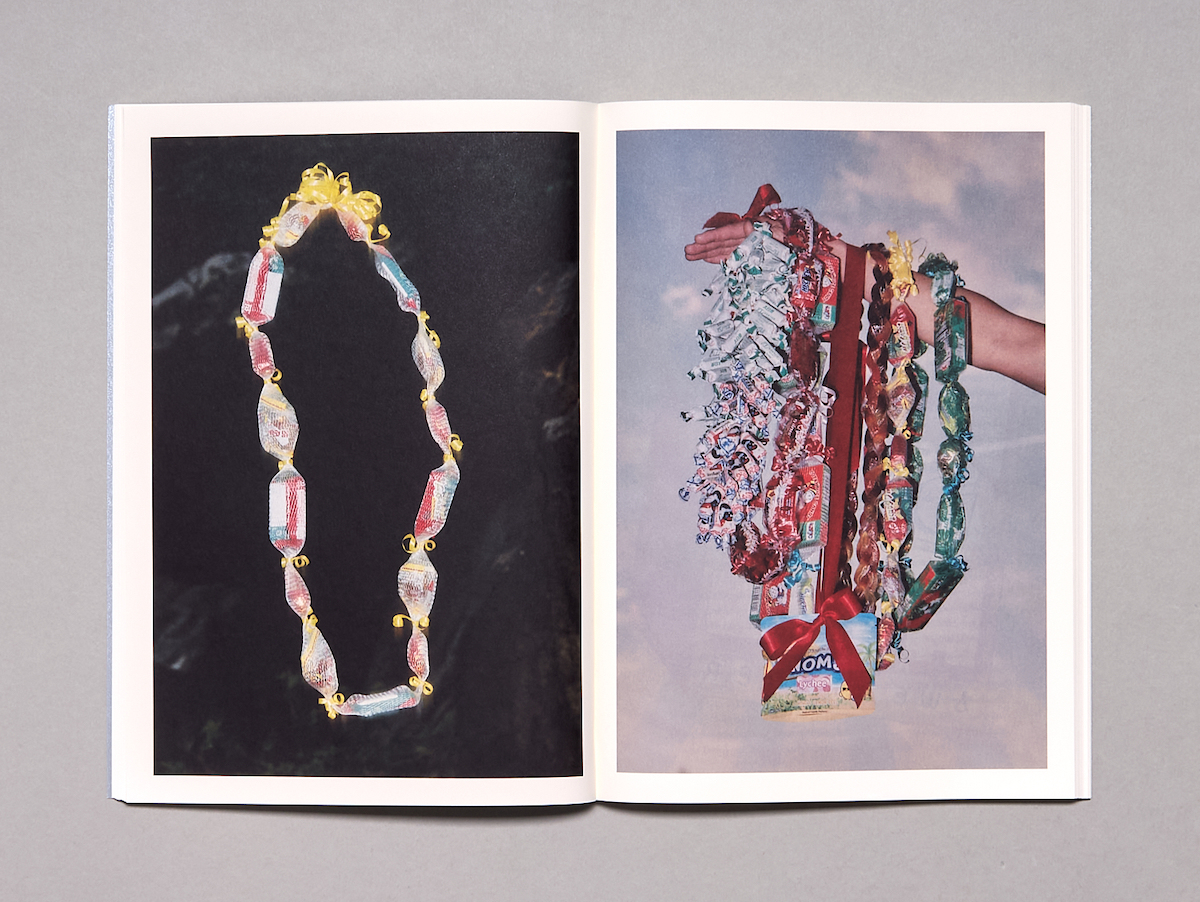

The launch party for this issue was no different from previous ones: a feast for the senses, especially taste, with botanical cotton candy spun onto flowers and Del Maguey-spiked mezcal jelly cakes. A few days earlier, I spoke with Tanya and Aliza about this new issue and the associations that it explores: candy as pleasure, childhood nostalgia, connection to distant cultures, as well as its roots in labor, gluttony, colonial extraction, and exploitation. With a diverse range of contributors unraveling these connections, Candy Land directs critical attention to familiar confections and flavors, highlighting their deeply person and historically global significance in their highly-processed and preserved glory.

Shop 'Cake Zine' Volume 05

Sofia D'Amico— Having just finished the Candy Land issue, I came away with the feeling that I’d read contributions from such a mix of people from different backgrounds— science, history, art, food industry, activism —and, of course, they’re each tackling the topic of candy from different angles. I am speaking from an arts background, but it’s a curatorial decision for these publications that you've put together such varied contributors. I’m curious how you pull together the community for each issue?

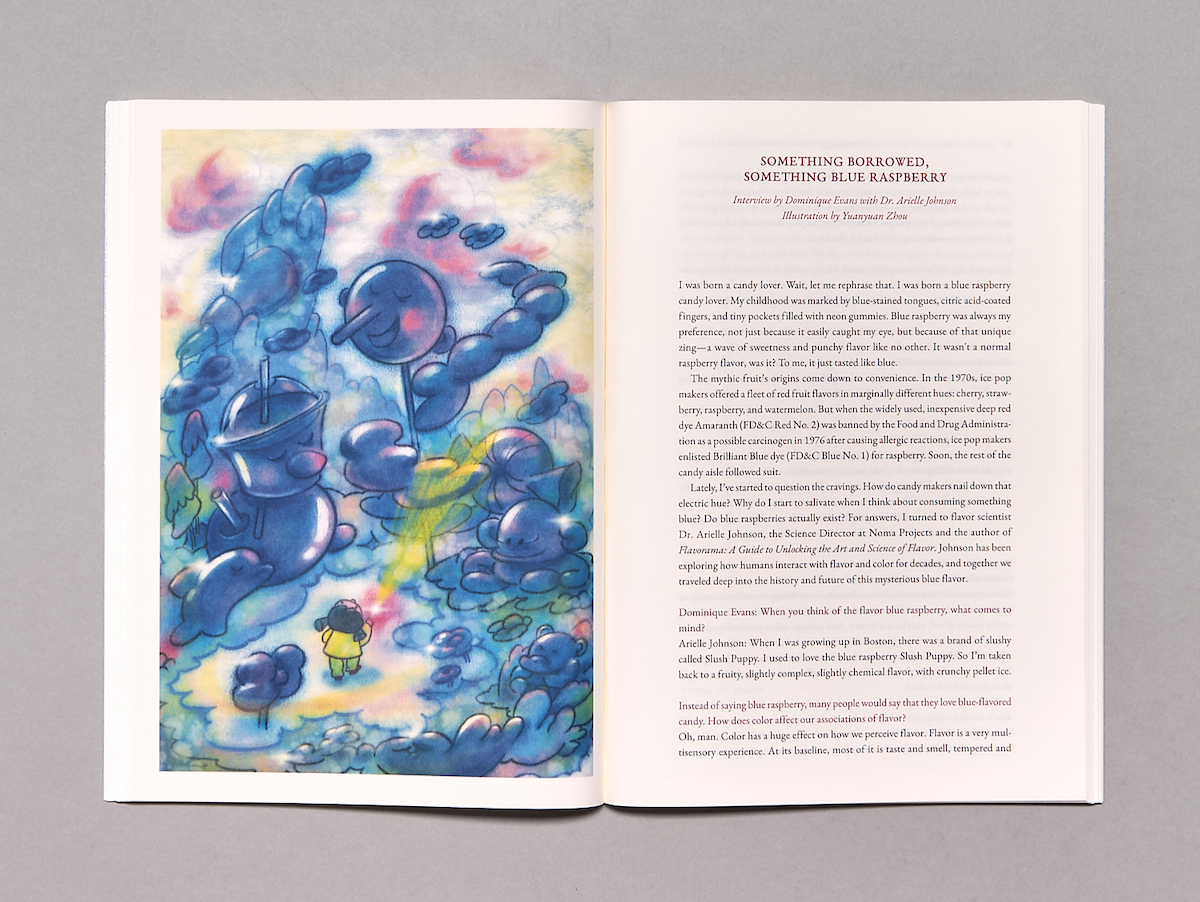

Aliza Abarbanel— The curatorial part of the process is the most core to what we do, and we are lucky to have a very robust community of people answering our pitch calls. At the end of every year we sit down and think about our themes for the year ahead. We had a really hard time deciding our summer issue and wanted to do ice cream, but we couldn't think about the right lens for the theme, because we don't just pick a food item, we want a specific context in which we're exploring and then refracting it in as many ways as possible. So with Candy Land, I played that board game all the time as a kid, and started thinking about how candy feels like it's so far removed from the land, but everything we eat is, at its core, tied to these organic ingredients. Candy has impacted the way we allocate and use land in different ways. So we set the pitch call in that framework, and get maybe 300 to 400 pitches per issue just for written content, not including illustration, and we also solicit from people. And as you've read, we probably have about 20 slots in an issue. Then a big part of what Tanya and I do with our editorial board is discussing how we can include as many different perspectives as possible.

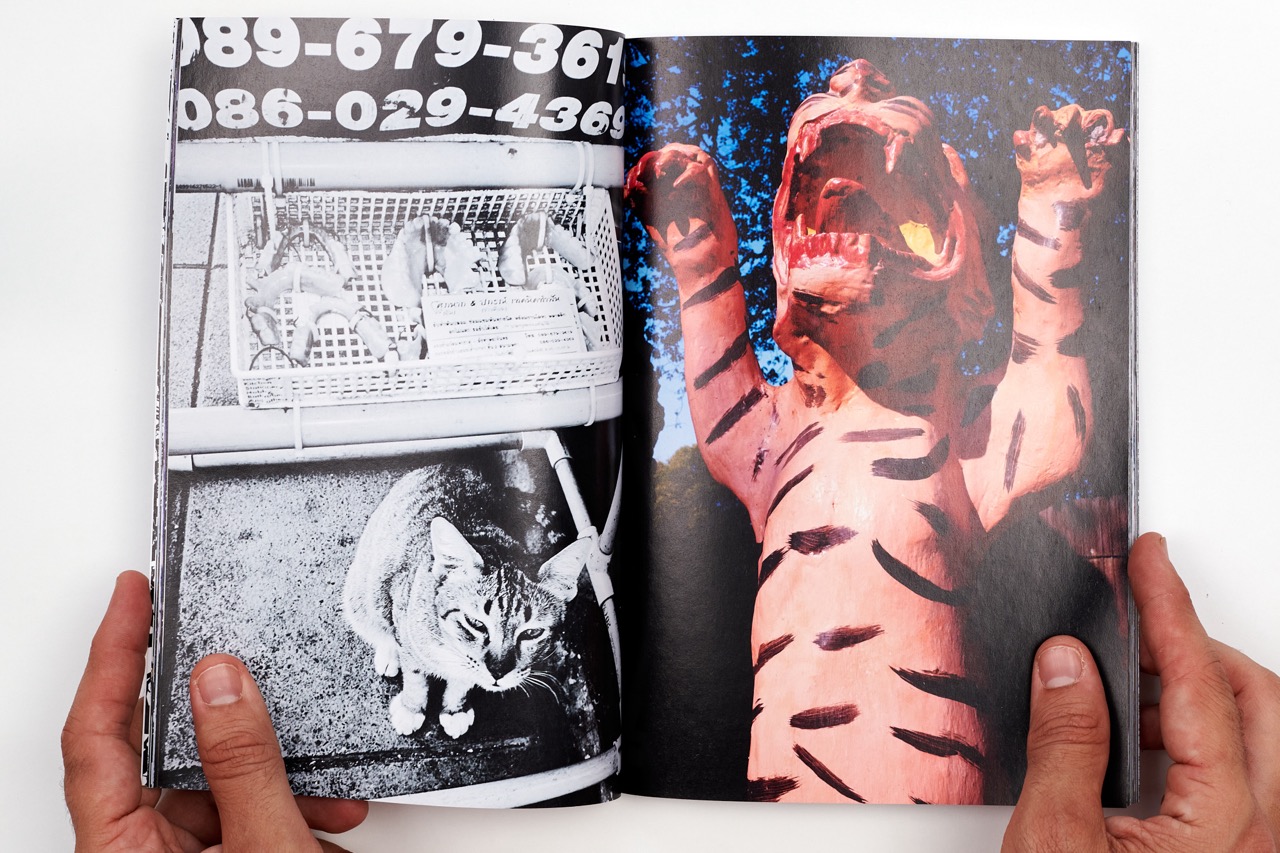

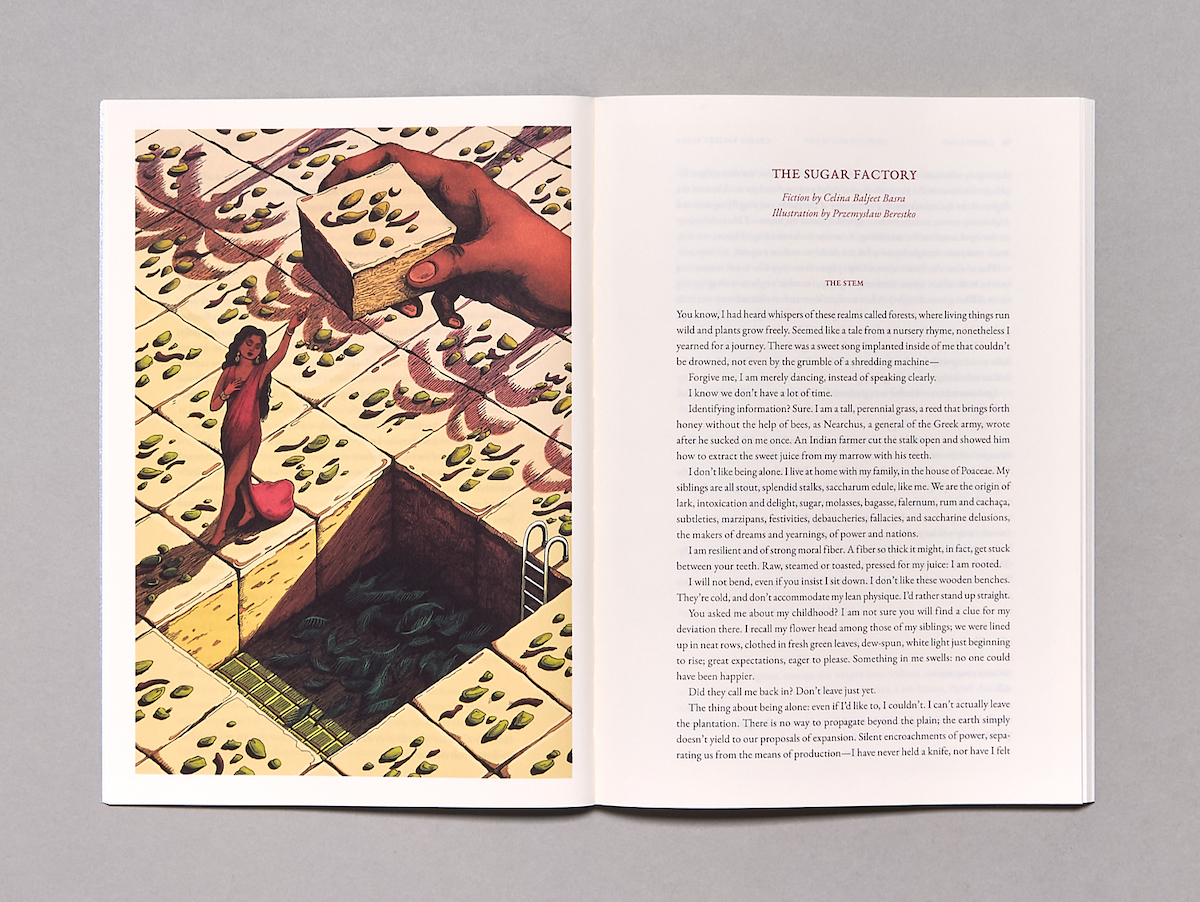

Tanya Bush— Yeah, I think that's core to the Cake Zine ethos, that we are an interdisciplinary magazine. We are using these very narrow lenses to explore culture, art, history, and food. That's sort of what Candy Land allows us to access; it’s an interesting subversion of themes. So we have the piece “Candy Land: A Revisionist History” by Elaine Mao on the actual board game Candy Land, but then we have a piece by Simon Wu on kandi with a K, EDM, raver culture, and PLUR. And I think that because we have such a narrow theme, it allows for writers, artists, cooks, and people of all different backgrounds to hone in on something really specific. We have our first piece of fan fiction in the issue, which was really exciting and strange. For every new magazine that we do, we want to incorporate unexpected forms: taxonomies, fables, and listicles. We did a comic once. That was fun.

SD— Yeah, this made it such a rollercoaster to go through. With this issue, some of the features were really funny and joyful or more didactic or historical, and others had really dark undertones. It is a nod to the endless associations that people have with candy itself, in that in some ways it’s a marker of nostalgia, and in others, it's about gluttony or excess. Do you think about that balance when you're putting together an issue?

TB— We don't want to publish a magazine that's an onslaught of darkness, so we are very much thinking of an issue holistically… We want there to be a dynamic balance of hard-hitting reporting and more optimistic features with levity, as one needs in a magazine about dessert. We are first and foremost a magazine about dessert.

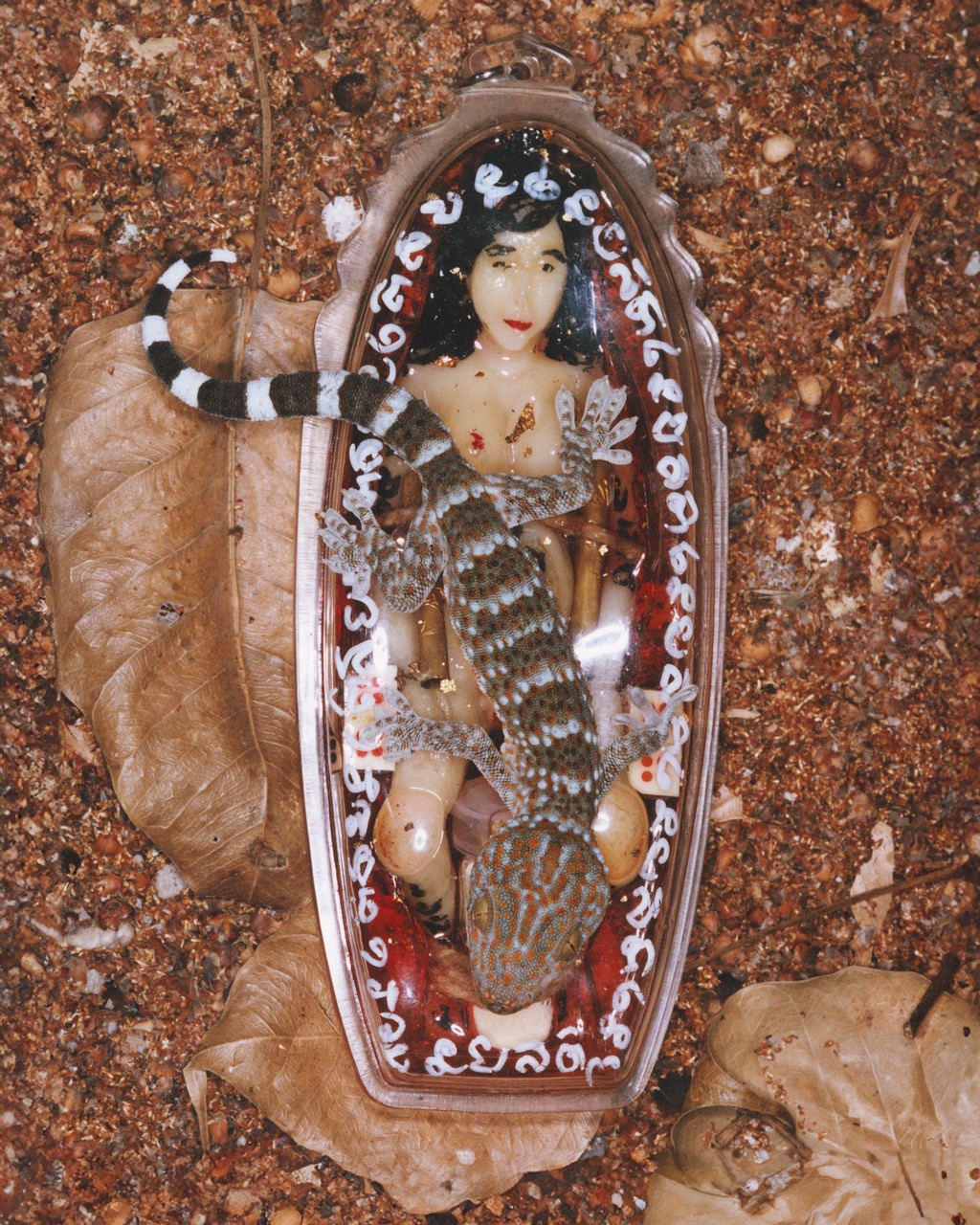

AA— With our issue Wicked Cake, the whole theme was talking about this dark side of a food like cake. I think famously of Matilda and Bruce Bogtrotter as a Wicked Cake thing that people would think about. But in general, cake is often super frivolous and fun. And for Candy Land, again, candy is so joyful. But more than any dessert we've covered so far, it's so linked to mass commodification, mass farming, and consumption. Most people don't make candy at home. We all know the history of the sugar trade in this country around the world, how it's linked to slavery and globalization and colonialism. A lot of these big corporations and their labor practices are impossible to ignore, so when tackling this theme, that was something that naturally came up. Part of doing a kaleidoscopic look at a theme would have to, of course, touch on that. But then we want the M&M fan fiction moment in there. We want someone who's diabetic talking about how sugar-free candy is campy and fun in the same moment, because those are obviously core to the candy experience in contemporary culture, too.

SD— And for both of you coming from the kind of food landscape, did you feel like there was a gap in a lot of publications and scenes that specifically connects food discourse with cultural production of different disciplines more widely?

AA— I think there are a lot of food publications that we really admire. I think MOLD and LinYee Yuan’s work is so incredible, and they do a lot of interdisciplinary and forward-thinking food work. Really, we did not intend to start what Cake Zine has become. We just wanted to make a magazine with our friends, then, very thankfully, we had a really great response to that issue and the party we did around it. That heartened us to keep going. Speaking for myself, leaving Conde Nast, I did want to make something that I could never justify to an international corporation business office as being a worthwhile pursuit.

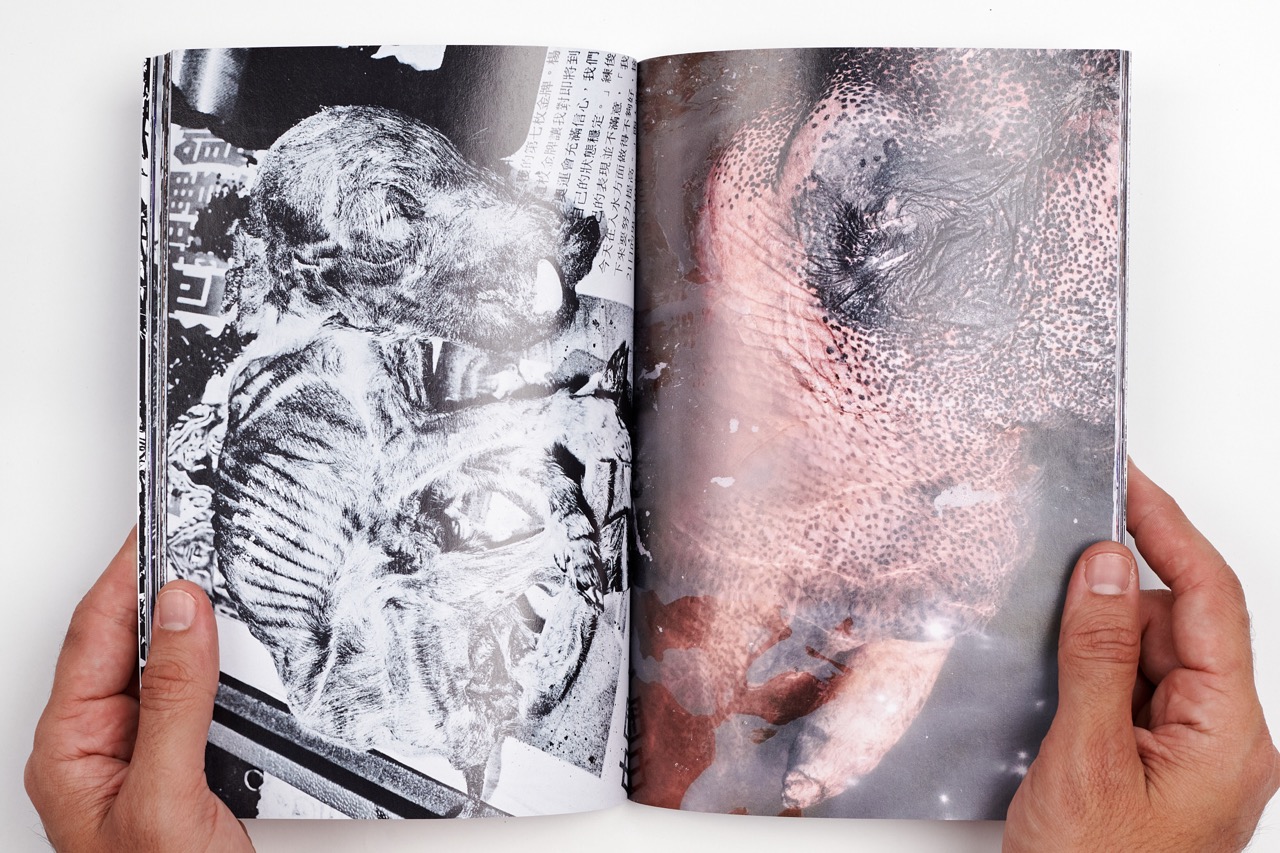

TB— And we are a print only publication, which I think is worth reiterating. We are not constrained by covering hyper-timely stories. As Aliza is saying, we literally cannot because we print in the UK, so it takes a few months to get books over, and if we're going to try and publish something super topical, it's already going to out of vogue by the time that it comes out. So I think that is really liberating and exciting because it means that we're not sort of beholden to the traditional constraints that a larger media publication needs to be. Because we have this sort of niche audience, people really resonate with the more historical literary approach that we take.