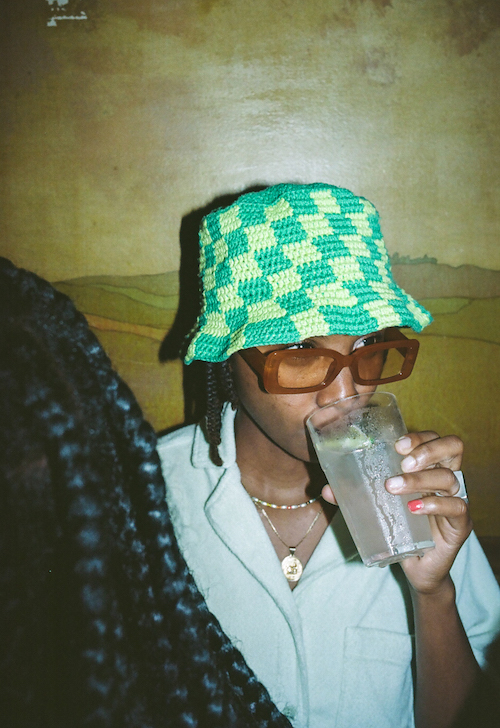

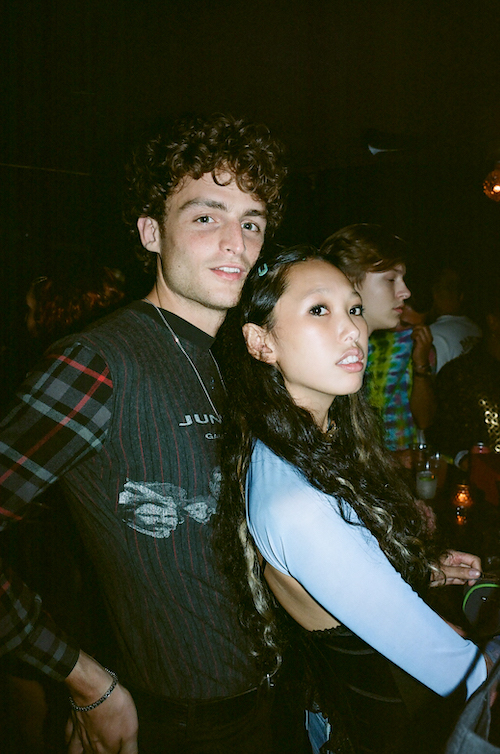

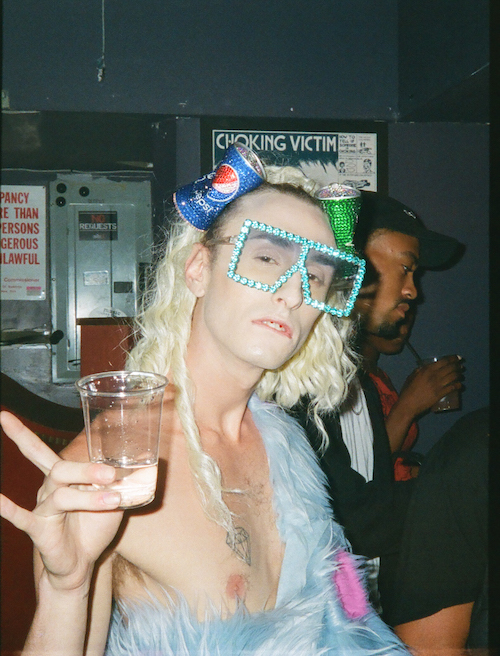

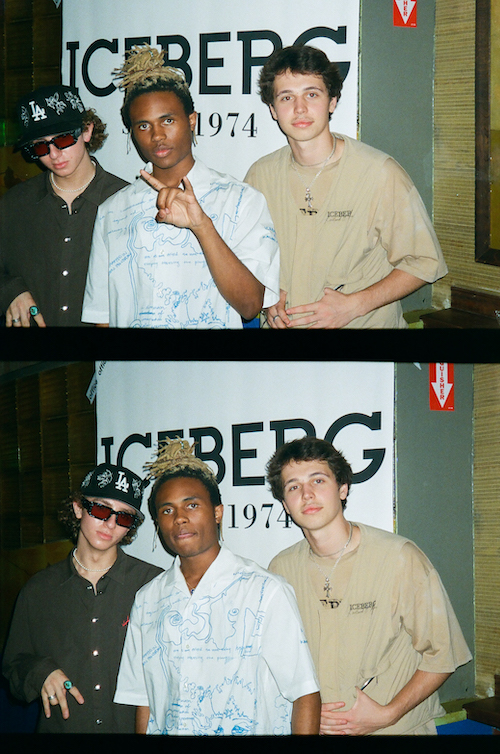

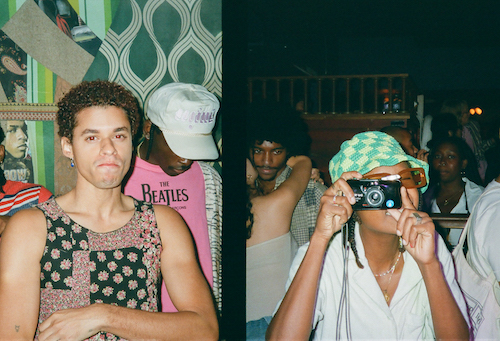

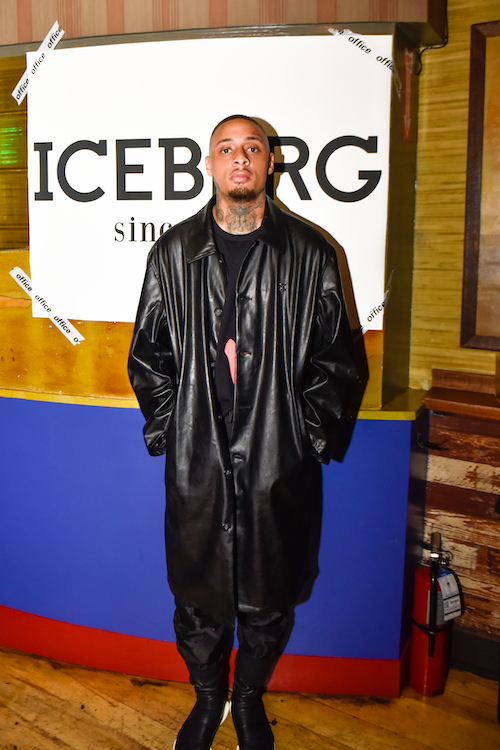

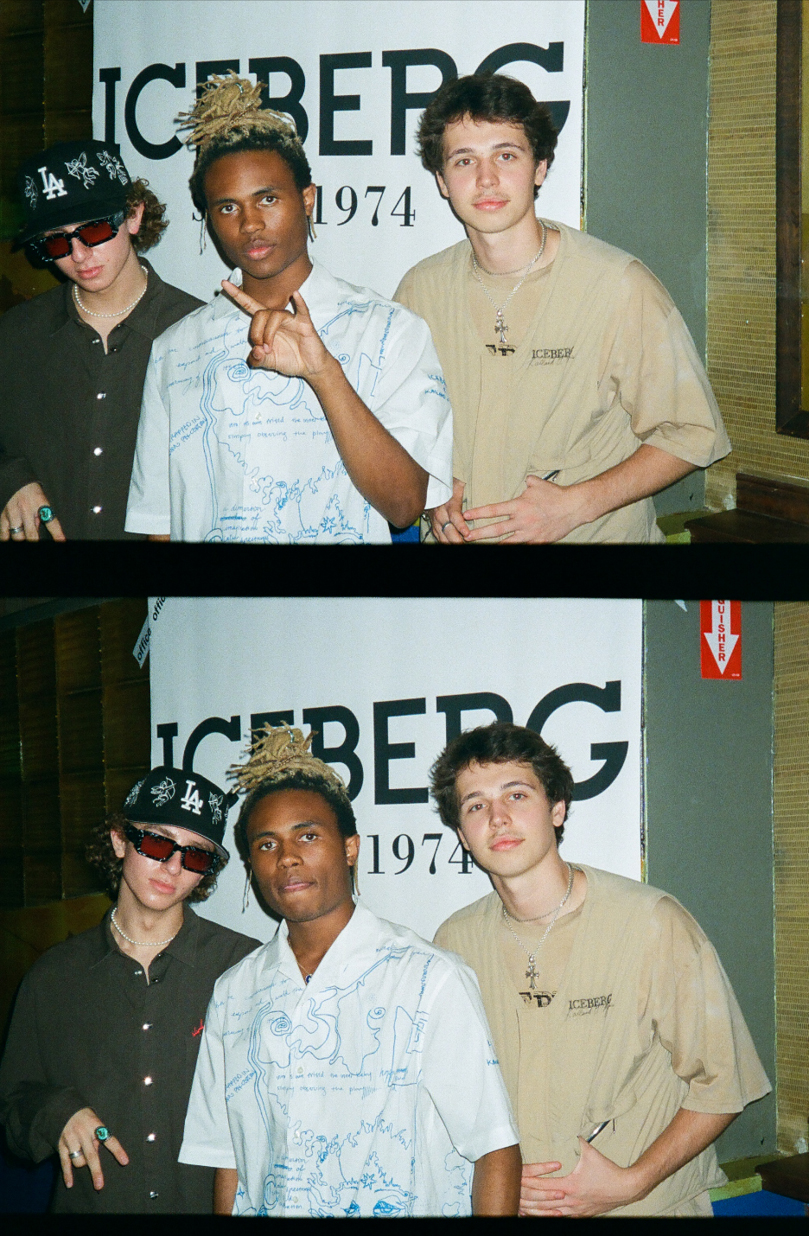

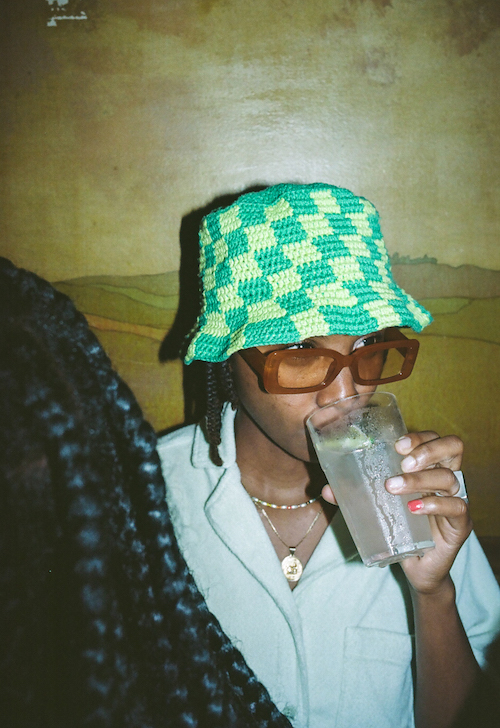

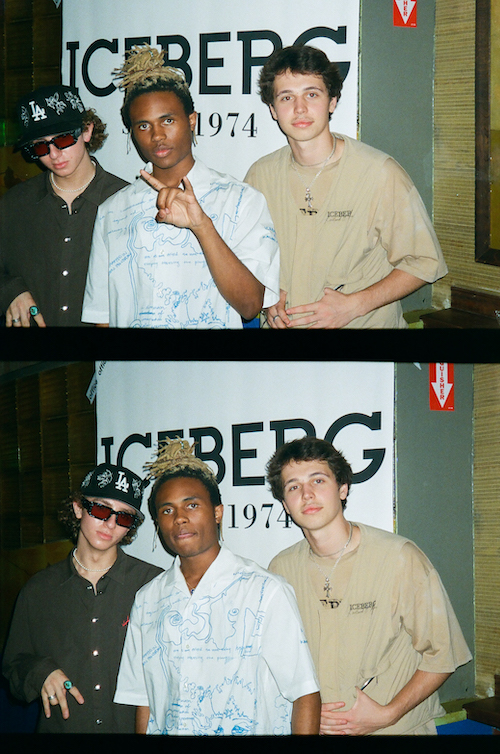

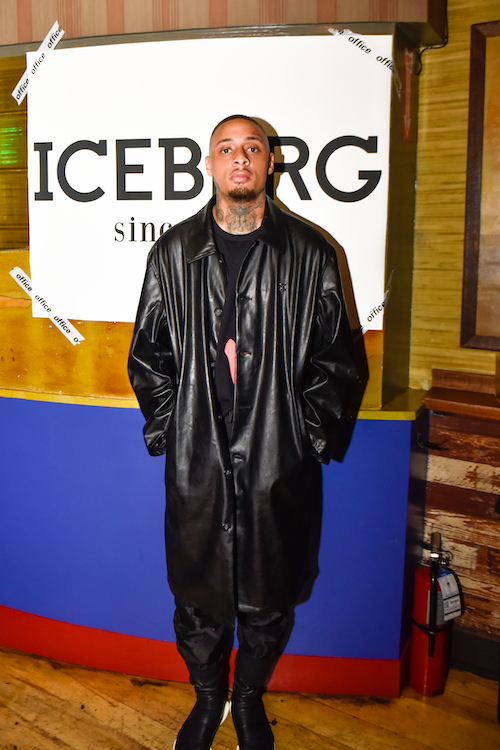

OFFICE MAGAZINE X ICEBERG NYFW PARTY

Stay informed on our latest news!

Mary Lou’s feels like a fever dream in the middle of Palm Beach — what sparked the idea, and how did it all come to life?

My partners and I, whether born here, raised here, or moved here, all eventually found our way through the nightlife scene in New York City. That golden era of NYC nightlife was the inspiration—the one where people danced without ego, DJs played undeniable music, and every kind of person felt welcome—was a huge inspiration for Mary Lou’s. It was nightlife at its best: free, unfiltered, and alive.

Palm Beach always felt like this aspirational world—bright, colorful, and rooted in a lifestyle of leisure and beauty. But for all its affluence and vibrancy, there was never really a venue that matched that energy or gave people a space to fully express it. That contrast always fascinated me, and I felt like it was needed.

Mary Lou’s is meant to be multi-dimensional—a space that doesn’t dictate how you should act, dress, or dance. It’s a choose-your-own-adventure kind of night. Programming is a major part of the magic: live bands, unexpected acts, eclectic DJs, dancers, and rotating performances all working together to create something fresh and unforgettable every time you walk through the door.

But we weren’t in a rush—we wanted the right space. Then we found Berto’s Bait and Tackle, this beautiful octagon of a building with soul in the walls and history in every corner. It felt like it was meant to be.

From there, it was about building the right team. One rooted in trust, pedigree, and a family-like bond. Everyone involved has been a rockstar in their own lane, and honestly, without every single person showing up and putting in the work, none of this would’ve happened. Mary Lou’s is a dream—but it’s one that took a whole lot of hustle to bring to life.

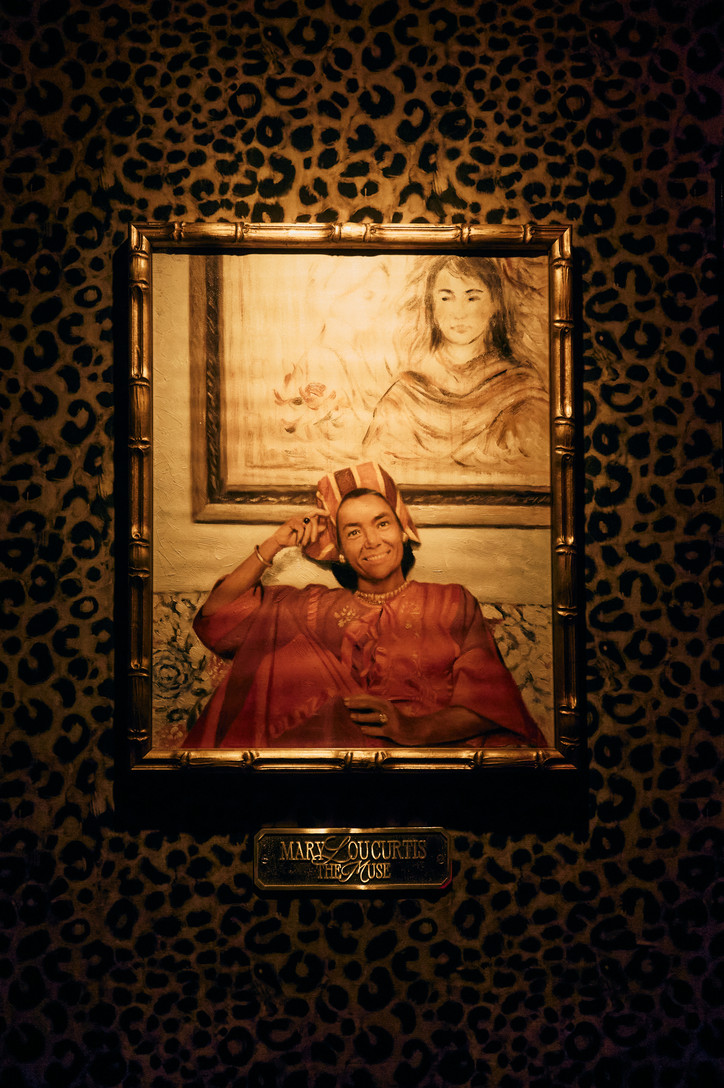

Let’s start with the name. Who is Mary Lou — myth, muse, alter ego?

Mary Lou was my grandmother, but never “grandma”—don’t even think about it. To her family and friends, she was always “Mama” or “Mama Lou.” The term “grandma” felt too old, too traditional, and too far from the vibrant, larger-than-life woman she was.

A celebrated fashion designer and successful entrepreneur, Mary Lou carved her own path in the world of style and retail. She was the founder of La Shack, a bold and beloved fashion brand that expanded to 14 stores nationwide, including a flagship boutique on Palm Beach’s iconic Worth Avenue. Unofficially, she’s even credited with pioneering the now-standard back zipper on women’s skirts and dresses—a small but revolutionary detail that perfectly captures her forward-thinking spirit.

But Mary Lou was so much more than her business success. She was a hostess in the truest sense of the word. Her homes in Locust Valley and Palm Beach were legendary gathering spots, known for unforgettable parties filled with laughter, dancing, and a rotating cast of close friends. She had a unique sense of style that extended beyond her wardrobe into her jewelry, interiors, and every detail of her surroundings. Her presence was magnetic—every room she walked into became brighter, more glamorous, more alive.

Mama Lou has been one of the most profound creative inspirations in my life. But when I set out to create Mary Lou’s, I didn’t want the concept to be about her—I wanted her to serve as the muse. A mythical figure. A spirit that guides the essence of the space. Mary Lou’s is not a tribute, it’s a feeling. It’s energy. It’s flair.

Mary Lou’s is meant to be bigger than life—just like Mama Lou. And that’s exactly how we want you to feel when you step inside.

Palm Beach isn’t exactly known for its nightlife. What made you bet on it as the backdrop for your club fantasy?

Honestly, I always thought it was the perfect backdrop. Palm Beach is affluent, aspirational, and built around a lifestyle of leisure, beauty, and success. The people are vibrant, the colors are bold, the fashion is playful, and there’s an underlying sense of joy in the air. It has this almost mythical energy—think Gatsby by the beach.

It checks every box for the kind of setting that deserves an iconic nightlife experience. The only thing missing was a space that gave people permission to let loose and have fun.

How would you describe the energy of Mary Lou’s on a good night — in three words or less?

In the moment

Who’s showing up to Mary Lou’s right now — and who are you hoping shows up next?

Celebrities, socialites, tastemakers, creatives—people who don’t take themselves too seriously but still appreciate great style, great energy, and a great time. Mary Lou’s is for those who love to have fun, who walk into a room and light it up, who know how to throw a look and hold a conversation. We like it just the way it is—authentic, effortless, and full of life. If you're in the room, you're meant to be there.

What was the hardest part about launching a nightlife space in a town that sleeps early and dresses conservatively?

I think that’s a bit of a misconception. Palm Beach doesn’t necessarily sleep early—it just likes to party in private. The nights are long here, they just tend to unfold behind the gates of beautiful homes, tucked-away estates, and boats. People go out for a great dinner, have a few drinks, and then the real fun kicks in—just not always in public.

What Palm Beach has been missing is a space that invites you to stay out, let loose, and feel completely at ease. Somewhere that blends the charm and elegance of the town with real, unfiltered fun. Trust me, I’ve had plenty of late nights here—it just needed the right stage.

As for the fashion? I welcome it all—bold, conservative, classic, experimental. Palm Beach style is more eclectic than people give it credit for. And to quote Mary Lou herself: “It’s better to be overdressed than underdressed, sweetheart.” That energy lives in everything we do.

Montauk

Nightlife is all about taste. What’s your personal filter for deciding what belongs inside Mary Lou’s and what doesn’t?

One of my favorite quotes is from Rick Rubin: “I don’t know anything, but I trust my taste.” That pretty much sums it up for me.

I approach Mary Lou’s through the lens of a student—of design, of emotion, of experience. I’m constantly observing what moves people, what feels timeless, and what sparks connection. My personal filter is intuitive. It’s about trusting my palate, trusting the feeling something gives you when you walk into a space, hear a sound, see a detail. If it doesn’t elevate the vibe, if it doesn’t spark a little curiosity or joy, it probably doesn’t belong.

Mary Lou’s isn’t built by committee—it’s built from instinct. Taste, for me, is about curation with conviction.

Talk to us about sound. Who’s spinning? Who’s dancing? And what’s the sonic signature of the space?

Mary Lou's is a unique space that is multi-generational. That is not only translated by the crowd in the room but also our sonic identity. Our focus is always on undeniable timeless music -- the kind of music that makes you want to put your phone down, dance and create memories. We focus on a mix of well-known artists like Sofi Tukker, LP Giobbi and the Chainsmokers playing our intimate venue for a once-in-a-Lifetime moment and tight curation of up-and-comers like CASSIMM, Moonlght and Julia Sandstorm so our guest can discover new favorites.

There’s an air of mystery around Mary Lou’s — how do you keep it exclusive without being exclusionary?

The magic of Mary Lou’s is that it feels like a secret—but it’s one we’re always happy to share. We keep things exclusive by keeping them intentional: the energy, the people, the experience. It’s about showing up with curiosity, confidence and a willingness to lean in.

Come curious, come ready, and bring the energy. While we do welcome walk-ins, reservations are always your best bet—especially on weekends when the room fills up fast. Dress like you’re going somewhere worth remembering. Be open. Be bold. Be ready to play.

For visitors, Mary Lou’s is a fresh take on Palm Beach—playful, unexpected, and rooted in a sense of discovery. And for those of us who built it, it’s personal. It’s a place with soul, history, and a little mischief—where everyone’s welcome, as long as they’re ready for a good time.

Paint us a picture: what does a peak moment at Mary Lou’s look like through your eyes?

Disco ball spinning, smiles everywhere. Not a cell phone in sight. People are dancing like no one’s watching—because no one is watching. It’s full release, total freedom. The kind of energy you can’t manufacture.

In my mind, it’s that perfect, surreal moment—Zoe Kravitz casually riding an alligator through the middle of the dance floor. Hands in the air, laughter echoing, every single person completely locked into the now. That’s peak Mary Lou’s. It’s magic, it’s mayhem, and it’s absolutely unforgettable.

Any stories you probably shouldn’t tell us… but will anyway?

We don’t kiss and tell.

Is Mary Lou’s a one-off dream, or the beginning of a bigger world you’re building?

Mary Lou’s has always been the foundation of a much bigger vision. In many ways, it’s the starting point of something new—but also a full-circle moment in the careers of my partners and I that’s been deeply rooted in hospitality, experience, and storytelling. It feels like the first chapter in the middle of the book.

At its core, our mission is simple: to create spaces and moments that make people feel something—that spark joy, connection, and a sense of escape, even if just for a night. Mary Lou’s is the spark, but the world we’re building around it is only just beginning to unfold. Stay tuned.

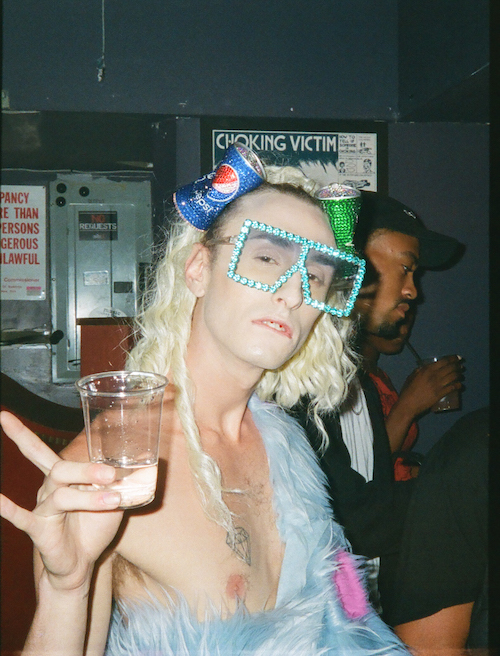

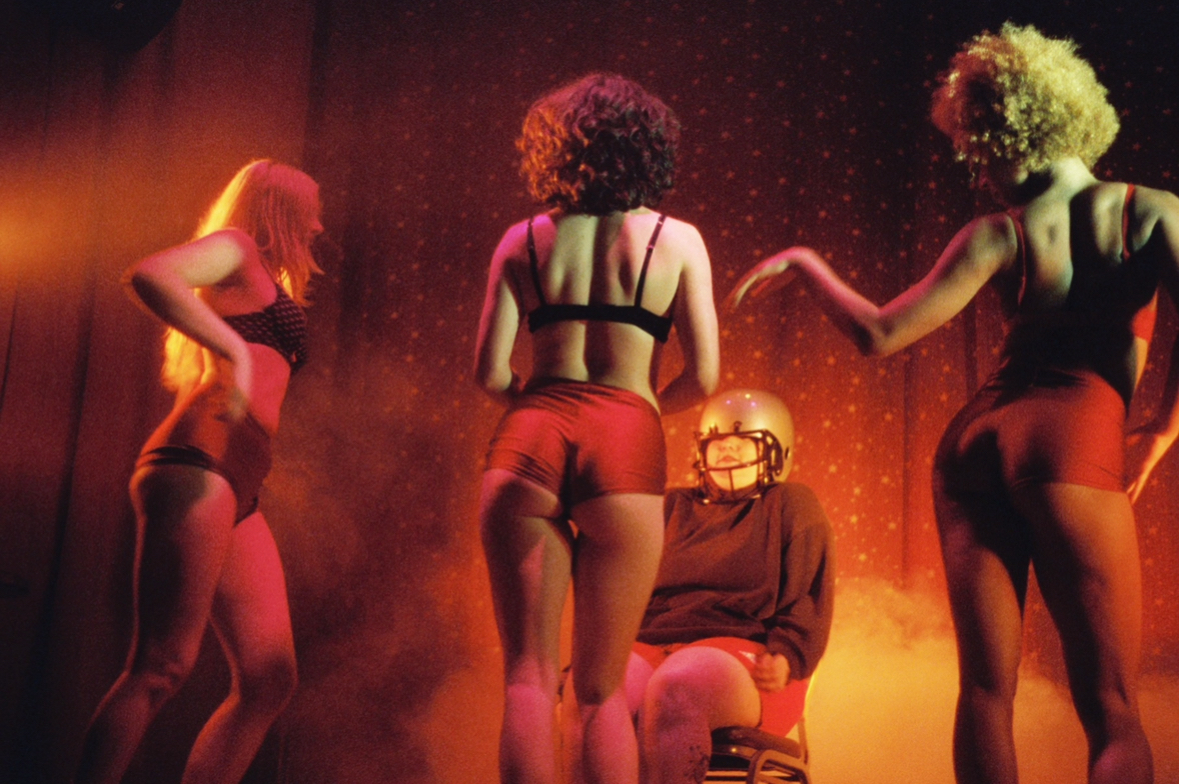

While many have flocked to the Slipper Room since its opening in 1999 to see the remarkable professional performances of dancing, singing, and seduction, I am seated on this Friday night to see a select group of performers who have never been on this stage, or any stage, ever before. This is the Virgin Show, dreamt up by Calder Mansfield, the tattooed brunette performer and bartender, with Faye, the taller and blonder event organizer and second generation of Slipper Room management. “It’s going to be burlesque, singing, stand-up comedy, and poetry, all while taking their clothes off,” Faye tells me while the aerial performer closes out her set. “I’m the organizer, and I still don’t know what to expect!”

As midnight approaches and a late night turns into the early morning, I sit a few rows away from the stage. The older crowd suddenly turns into a younger one as beautiful boys and girls of New York’s downtown slink into the seats and standing room surrounding me. My pen is poised above my mini Moleskine and I pull the tea candle on the round table closer to me. I have no idea what I’m about to witness and I refuse to miss a moment by attempting to take notes on my phone, its blue light penetrating the darkness that signals the show is about to begin.

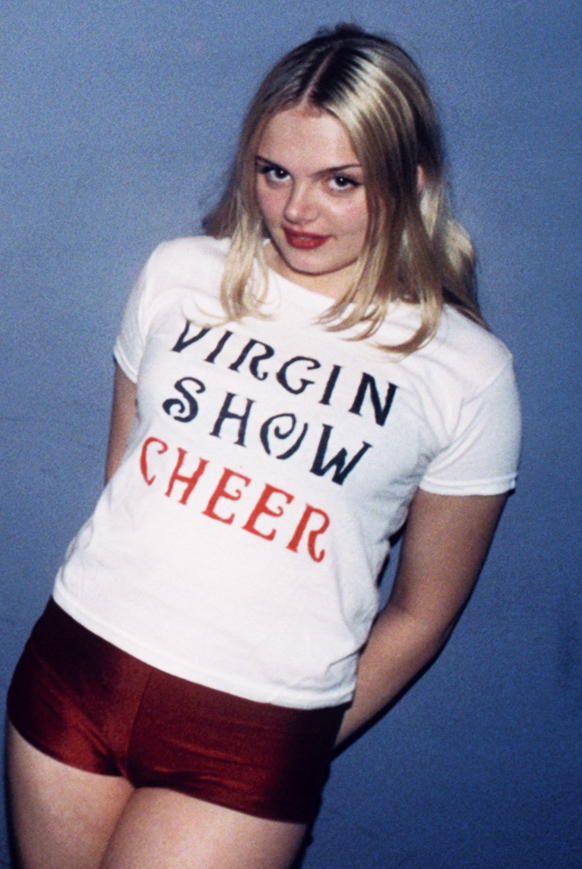

The first character to step in front of the red velvet curtains is Coach Mansfield, Calder Mansfield’s alter ego, wearing a black sweatshirt, red basketball shorts, mismatched gym socks, no shoes, and a football helmet over her head. She barks at the crowd, congratulates the college graduates of 2025, and introduces the Virgin Show before launching into an extraordinary rendition of “Maybe This Time” by Liza Minelli with a slightly more aggressive, modern twist. Her vocals are impressive, demanding, and effortless. Then, the curtains open to the anthem “Everlong” by the Foo Fighters, and Faye and two other dancers surround the coach in a flurry of pom-poms, mini shorts, and “Virgin Show Cheer” t-shirts, breaking into an endearingly choreographed burlesque and cheer routine, twisting, turning, and smiling. Suddenly their shirts are off, and the performance ends with the girls in nothing but thongs, pasties, and pom-poms.

The organizers include a seasoned professional in the line-up to encourage and inspire the newbies. Jenny C’est Quoi, clearly not a virgin to the stage, stands in a graduation cap and gown and towering patent leather platform heels as the red velvet curtains open. Smoke slithers onto the stage behind her as she removes a tube of sunscreen from her gown as a comedic audio warning of sunburn and global warming plays. She lip-syncs, lathers, and strips, combining the themes of graduation, environmental apocalypse, and comedic timing, into a burlesque performance. An expert indeed.

Faye and Mansfield are then joined on stage by comedian and Anora actress Ivy Wolk to play a game they called “Who Has The Most Useless College Degree?” Audience members wave enthusiastically, volunteering themselves and their friends for the educational roast that was bound to ensue. Lined up on stage, one volunteer proudly states that her musical theater degree is the most futile, while other contenders volunteer their fashion design, media studies, and printmaking diplomas as fuel to the fire. Wolk prods each person with unexpected quips. “Have you ever been to rehab?” she asks the printmaker, who responds enthusiastically, “Yes!” Everyone applauds. Faye walks down the line, asking the audience to cheer for the contestant who pleaded the strongest case. Musical theater is declared the winner. The reward? A free drink at the bar.

Next, Charlene ascends the stage with an original poetry reading wearing an orange feather boa, corduroy overalls, and not much else. “Oh my god, I was so nervous,” she confesses to me after the show. Mere minutes before, she had suavely removed her red rubber gloves with her teeth. Despite taking dance classes at the New York School of Burlesque, her heart still pounded as she revealed the most vulnerable parts of herself, her words and her body, to a live audience. “My poetry is about ownership, bodies, and sexuality,” she explains. Involving burlesque elements to her work is a method of pushing herself to new experimental and artistic heights: “It was actually really fun.”

Wolk returns for a final set of in-person shit-posting for which she’s known and loved. In her monotone voice, she hurls ingenious lines at the crowd who are so shocked by her relentless boundary-crossing humor that they can’t help but cry-laugh. Tears stream down my face as she cements her stage presence as something between a brain-rotted middle schooler who lacks social awareness and two gorgeous sports cars wrecked on the side of a highway: a beautifully obnoxious crime scene where nothing is off limits, from her uneven bangs to her gag reflex, her diagnosed anorexic adulthood to her desire to be dragged beneath the tires of a car. As she comedically violates herself, Wolk remains clothed in her striped turtleneck, leather jacket, and jeans. In contrast to the previous performers who bare all, Wolk confirms that the stage is first and foremost meant for a creative expression no matter how many garments a performer chooses to wear.

To culminate the show is Lady Lump, reclined on a beach chaise while wearing a leopard-print bra and underwear, lacey blue garters, and microbangs. She flirts with the inflatable alligator pool toy in the chair next to her, peeling off her lace gloves and seductively rolling in the imaginary sand. By the end of the show, I had seen cheerleader strip routines, confessional poetry, stand-up comedy, and a satisfactory number of rhinestone pasties. The Virgin Show defines contemporary burlesque: It is an exciting homage to classic raunchy performance while appealing to the modern desire for an intersection of sex and smarts.

Faye feeds the fire of her family’s legacy by inspiring burlesque in younger generations via her Virgin Shows. “I was so fortunate to grow up in this space,” she tells me backstage. “There’s an energy here that I want everybody to experience.” Her parents opened Slipper Room at the turn of the century, yet their stories of New York span much further back. Faye repeats an old story from her mother of a derelict, rusted boat turned underground club many decades before. “It would get so hot in the summer that the boat’s metal would sweat, so it would sort of rain inside of the boat. I hear stories like that and they’re so authentic, so carefree,” she explains. “I’m trying to create a space where everybody feels like they’re dancing in that boat rain. Where nothing matters, they can just watch this [show] and be captivated by it.” She yearns for the old New York, as do I, whose artists and performers transformed the city into the magnetic metropolis that lured me and many others from across the country and around the world. But Veronica was raised here, nurtured by the downtown noise and grit that grant her vision the natural edge that most people spend a lifetime developing. While she loves her parent’s tales, now she’s driven to create stories for the next generation.

At the core of the Virgin Show’s ethos is creative release and celebration. Mansfield started at the Slipper Room three years ago and loved the idea of burlesque, yet felt unsure whether the stage was for her. “When I first started working at Slipper Room, I was at a really weird place with my body. I didn’t feel beautiful in it, and I didn’t feel comfortable in it,” she confesses. But that changed when she saw the diversity of bodies on stage. “Seeing dancers built like me and who look like me just changed something. I would leave every night with this sexy pep in my step. I value that feeling and I’m so grateful for that feeling. I want to share that.” The beauty of burlesque relies on a performer’s body, but more so on the raw vulnerability and confidence it takes to simply do it. “If you have the balls to get up on stage and pour your heart out, you’re welcome here and we want to make space for you,” Faye exclaims backstage as the performers re-dress and wave their goodbyes.

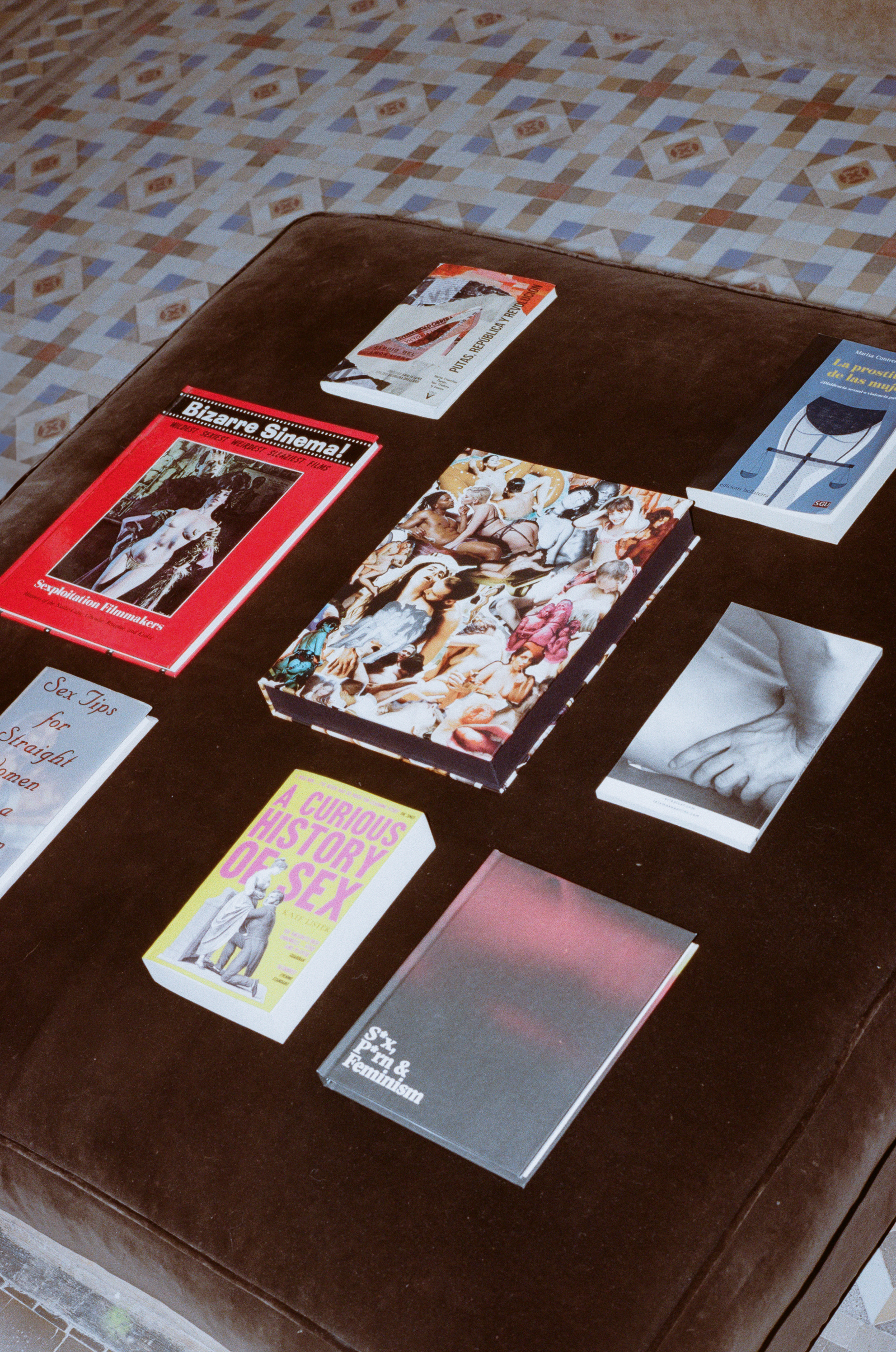

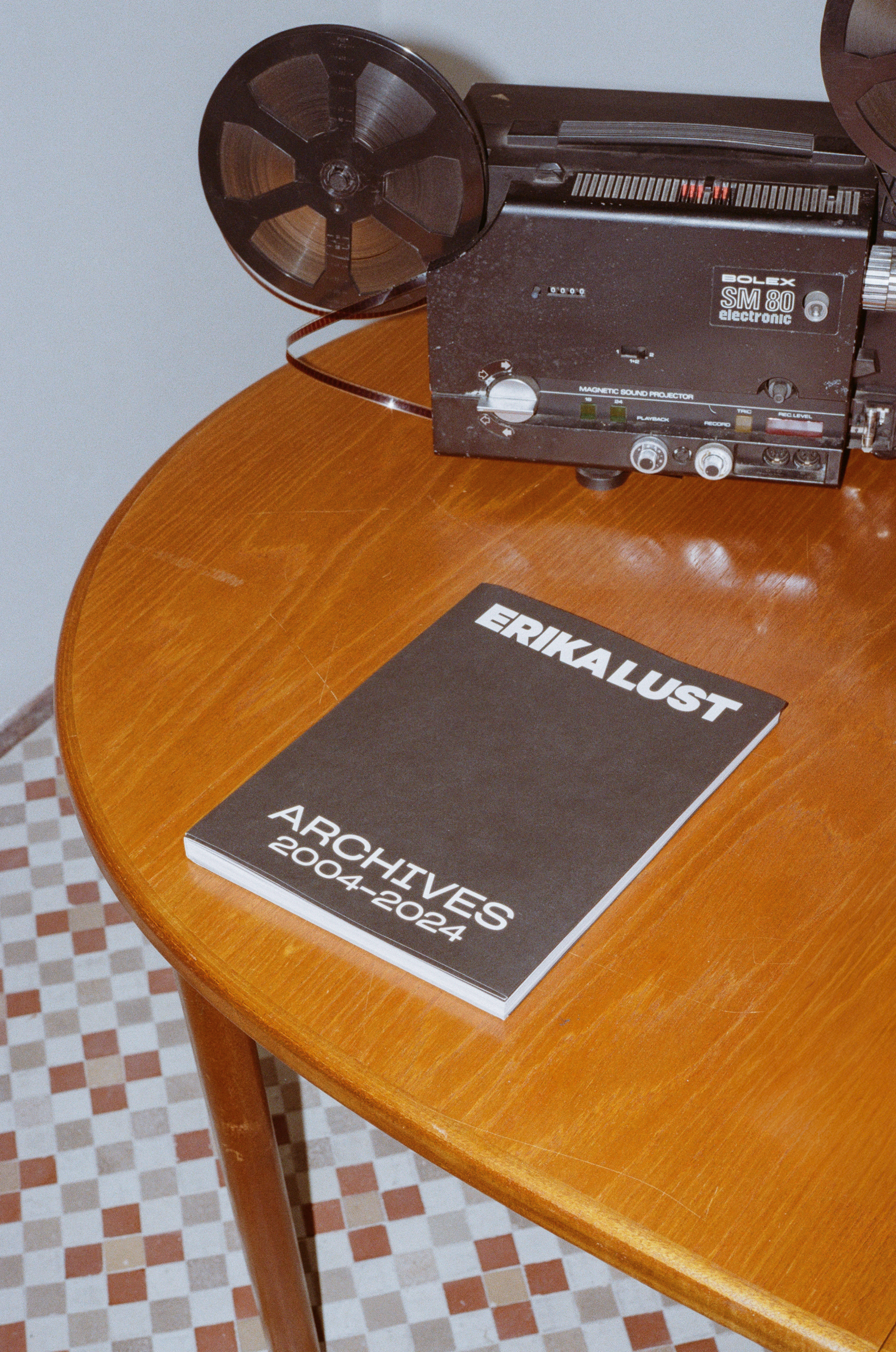

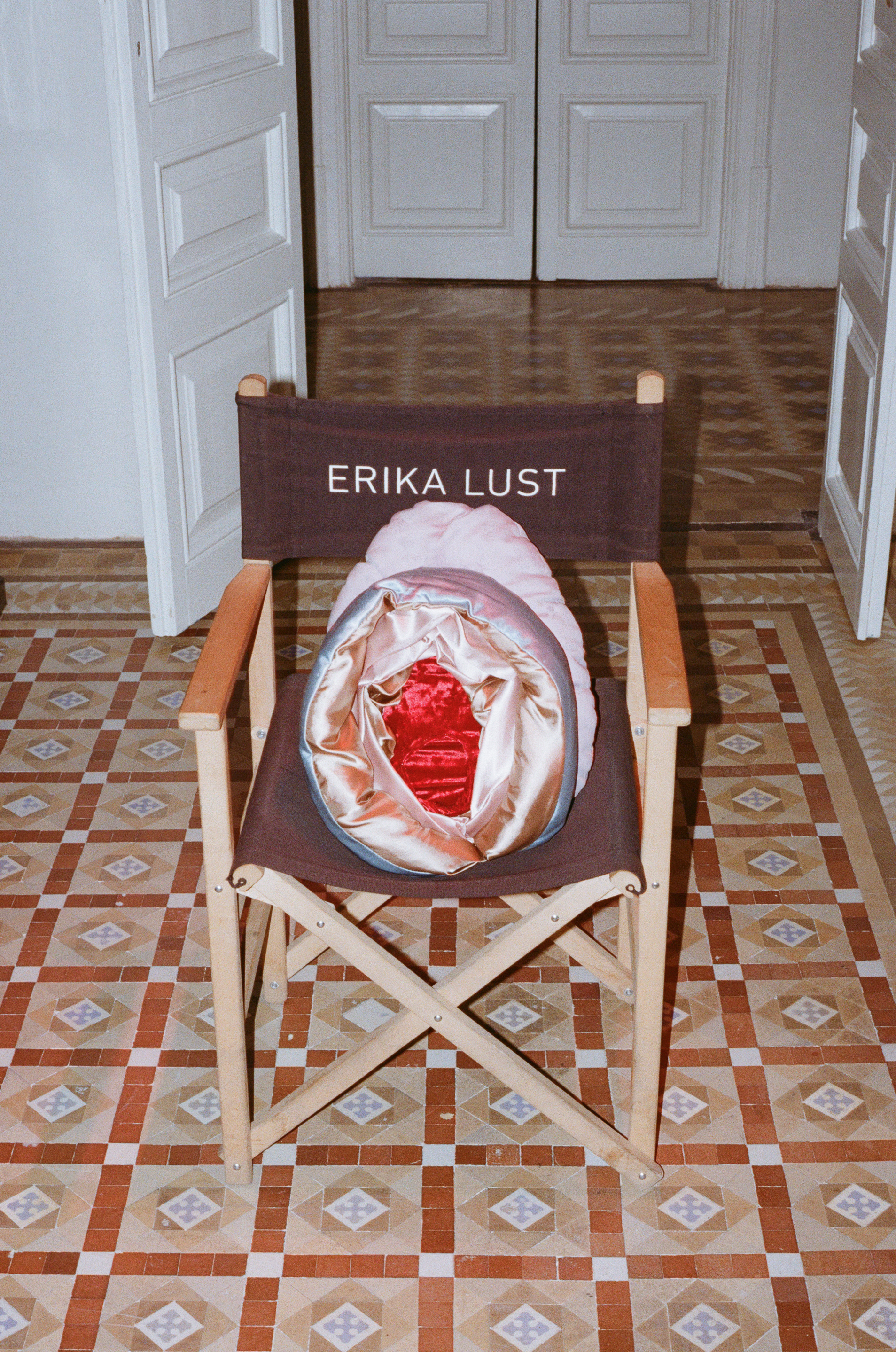

The concept of the salon experience is not a new one. Looking back to almost a century ago, Gertrude Stein would throw exclusive parties in her apartment for surrealist luminaries and in doing so provided them with a space for open dialogue. At the iconic 27 rue de Fleurus in Paris, a free-flowing exchange of ideas was made possible through a collaborative and curious spirit. Boasting some impressive names such as Henri Matisse and Ernest Hemingway, the guest list was habitually stacked with unique characters who were not shy to observe the female form. In an effort to continue that legacy, introducing the Lust Salon experience emphasizes the importance of these in-person spaces.

The following day, I got a private tour of Lust Production’s office space and it’s no surprise that risks were taken with the interior design. The office is located in a sprawling sun-lit apartment in L’Eixample that used to house a notably opulent Spanish family. It might look a tad different now considering the erotic photographs spread across the walls and the clever addition of a phallic-shaped bottle opener making its way into the communal kitchen. Her personal office is situated in the old master bedroom where a small chapel was attached so the previous tenants could always be close to their faith. Today, in its place, stands her dimly lit masturbation room including a fluffy bed and oversized plaid dildo pillow. Definitely unorthodox, but that’s what we love about her.

A couple of hours before the event and tucked away in a crowded café in Barcelona, I was able to start a dialogue with Erika, getting to know more about her and what she hopes these salons will bring to the cultural landscape. The event was the first in what will be a series of intimate gatherings across cities manufactured to bring everything Erika Lust stands for into collective, in-person spaces. She’s a very inspiring person to have a conversation with, especially because of her rare openness in a world of increased censorship.

Is there an era of porn before the contemporary age that you are particularly inspired by?

I think that it depends on how we choose to define porn because if we talk about just explicit sex, it can go even further back to Ars Erotica which comes from all cultures. It comes from Kama Sutra and Shunga and has been around since forever. But then if we think about what people normally recognize as porn today, it's photography or video, right? They don't think about art as porn. They don't think about paintings. They don't think about literature as porn even though audio-erotica is starting to become more of a thing.

But the movies of the 60s and the 70s, they were movies. They were done by filmmakers, by artists, by people who somehow had this perspective that was reacting to a very conservative culture. They were showing a more liberal way of living through their films. If you look at their films, they were shot cinematically, they had some kind of narrative, they had visuals that were quite impressive for the times and were even played in big theaters.

Isn't that crazy? Today, they would never...

I mean, we've done it. We've done shows in big theaters to bring the films out there and get the audiences to look at the work from a whole different perspective. We wanted to bring it into the communal experience instead of just, you know, yourself [alone] in the bathroom with your mobile phone [laughs].

[laughs] Yep. The salon is another way of doing that because it brings those visuals into a shared space with other people. What do you think that means today?

I think it means a lot. It's very, very interesting to bring it back because this was part of the world before technology started to isolate us and make us into these robots that are connecting, not with the person we're sitting in front of, but through our mobiles. It's quite absurd, actually, and it's really necessary to create these spaces where people are not on their phones, but they are looking into each other's eyes and communicating. They are speaking with an open heart, trying not to be afraid of saying something wrong and being judged.

We need to be very aware of the censorship that we are committing towards ourselves. I think it's dangerous. It stops the free flow of energy, thought and communication. But you only dare to do it if you feel safe. If you don't feel safe, you're not going to say what you really think so we need to create spaces where we feel safe to talk. Spaces where we feel inspired and connected.The experience of shared pornography has existed for quite a while but mostly in the experience of heterosexual, white, rich cis men in bordels [brothels]. That's where they started to share those kinds of images and part of why that particular group still feels so entitled to their pleasure, to their entertainment, to everybody serving their sexuality.

So how do you feel that something like the salon or even your series on guided masturbation

[After Hours by Erika Lust] can help people feel more comfortable or represented?

It's similar to the films. Somehow, it's showing a different narrative where you feel that you can have an active role. Especially from a female point of view, women are not reduced to a beautiful object or to someone who will just serve the other person. It's a place where we can see ourselves portrayed in a way that makes us feel more whole, more real, more us.

Just take a moment with the erotica or these sessions to relax. The world is so fast- paced that taking a little time for yourself is almost revolutionary. This is something that I see a lot with women who are in relationships, especially women who are living with cis men. They tend to disconnect from their own sexuality and start to see it as something that they only do with their partner. But I honestly think that it's very important, even if you are in a relationship, to keep being your own person and keep that relationship to your own sexuality. If you lose that, it's gonna have an effect on your power and self-worth.

I mean, in cis relationships so much revolves around the male point of view of things, no matter how amazing men can be. The systems are built around us, promoting that.

I think that women tend to adapt much more than men when they go into a relationship.

Do you see your audience as being mostly women?

When I think about my audience I always picture it being female and diverse. I picture my friends. But then the reality is that when I look at the numbers, it's not exactly the truth. We have around 60% male subscribers which is kind of surprising because we are associated with porn for women. It's quite interesting to see that what we do interests men and I think it has a lot to do with how masculinity is changing.There are many more men opening up to a new way of understanding sexuality and are very curious about the female point of view.

I do know that many of those subscribers are couples so it might be a man's credit card because we all know that they are used more to pay online. I mean look at women, it's been five minutes since we've been allowed to have a bank account, a job, or our own economy. When we look at our social media followers, it’s a different story. That’s 90% women [and queer people].

For the salons, what inspired you and the team to do these in-person events?

Events have always been a part of this [Erika Lust] since we started. We've done events all over. In Silver Lake [Los Angeles], we had a big screen and invited lots of people to come and watch our films. We've done many events at Soho Houses around the world because they are friendly with our kind of cinema, you know [smiles]?

We're always trying to get into more cultural spaces. But this time around, what we are starting today here in Barcelona, is a smaller, more intimate circle where we can touch on subjects like pleasure, pornography, and filmmaking. We're inviting more local artists and the plan is to bring them to New York and to London and to Paris and tour around a little bit.

Wow. So a tour with the same group artists in each city. What kind of artists do you feel like are most important?

I'm a huge fan of dance. My little sister was a classical ballerina when she was younger and I love it. I love dance. From the time she was six years old she would dance six days a week at the theater and I would have tickets to all of the shows so I've seen everything. Many of my films even have dance teams in them...everything from salsa to alternative. Dance is about being in our bodies which is something which is something I struggle with quite a lot.

We all tend to compare ourselves to our sisters and brothers, right? I always felt clumsy and my parents told me I was the brain and she was the body. I was good in school and she was the dancer. So then when I wanted to do theater my mom said, "It's enough with one artist in the family." And here I am.

Here we are now. You did not listen to her. Little did she know.