office.mp3: Feeling Fem

It's Women's History Month, so we're showing some serious love from home to our favorite female artists. Pass the time at your casa, and share it with your cat, your plant and your friends on FaceTime.

Stay informed on our latest news!

It's Women's History Month, so we're showing some serious love from home to our favorite female artists. Pass the time at your casa, and share it with your cat, your plant and your friends on FaceTime.

When did music become a thing for you?

Music was always a way to feel connected to Lebanon. I was born in Tripoli, in Lebanon, and moved to London when I was six years old. I remember my mum playing Fairuz in the morning, and Umm Kulthum at night. When we’d go for drives in the car together, we’d listen to Wael Kfoury, Najwa Karam, Elissa, Nawal Al Zoghbi…

I was obsessed with Star Academy, this 24-hour Lebanese TV channel kind of like the X Factor, where you’d see singers doing vocal exercises, note reading, music theory. I actually auditioned a couple of times to go on the show when I was younger.

I was also really into performing arts and musical theater like the Rahbani musicals. I would secretly go to ballet at Urdang, a performing arts college near Farringdon, until my dad caught me with my ballet clothes one time and stopped my pocket money. So I never really had the opportunity to explore that side of myself when I was younger.

Would UK sounds play into that, at all?

I didn’t actually know who the Beatles were when I started Music at school. Or Amy Winehouse, Madonna, Destiny’s Child… none of that! I got heavily bullied for it. People weren’t curious about the music I liked, and there wasn’t much room for songs outside of the curriculum anyway.

Okay, wow. I didn’t realize that!

Yeah! This is something that has stayed with me throughout the years. It’s been a constant chase for a community that’s connected by Arabic music.

Did trips to Lebanon ever bring a sense of reconciliation, then?

Sort of. I’d take vocal training classes there over the summers, but I felt limited to a specific style. It was very gendered: the repertoire for men was songs by Zaki Nassif, Nasri Shamseddine and Wadih El Safi. I just wanted to sing Carole Samaha! I was much more drawn to the female sound, the softness and gentleness.

What’s been your approach to learning and growing as a music artist?

I think on the one hand, I’ve often tied my musical talent and ability to qualifications, so I was always chasing this idea of being formally trained in Arabic music, as many traditional artists do. I do really enjoy focusing on traditional Arabic singing, for the way it highlights the maqams,* and for how long and sophisticated the finished piece turns out. So after I graduated from university, I moved to Lebanon for a longer period of time to start vocal training. I took courses at USEK, the Holy Spirit of Kaslik with Ghada Shbeir, who specializes in Arabic, Syriac, Arameic music and muwashhahat(a poetic form that uses complex rhythms originating from Al Andalus).

But at the same time, I didn’t want to be tied to a certain curriculum that focused exclusively on tarab.** I wanted to learn about pop singers too! I listen to Assala, Sherine… I mean, Haifa Wehbe, one of the most iconic pop singers, got a lot of media backlash at first because she wasn’t technically trained in tarab like most musicians at the time. But that welcomed this era of Arab pop stars like Marwa, Myriam Fares, Nancy Ajram, Nicole Saba, where it became just as much about their image as their musicianship.

*A 24-tone melodic mode system, consisting of microtones, built on a scale of 7 notes.

** Loosely meaning ‘enchantment,’ tarab is a traditional artform that unfolds as a long, stirring musical performance that coaxes the audience into a state of rapture.

So it’s about honoring the old and new, for you?

Yeah, and this is something I’m exploring currently in my own music, embedding maqams into my sound as a way to preserve the culture. There’s an absence of sophisticated maqams in Arabic pop music today. I want to be able to take classical Arabic music but make it my own, as someone who grew up in London, and bridge the identities.

When was the moment you started to view yourself as a music artist, or take your singing seriously?

A few years ago, I went to a Pride of Arabia party in London and it was the first time I felt that being Arab and queer could coexist. What I loved about the community was how we were able to speak in Arabic to each other. Language is so important to me. That — as well as Pxssy Palace — was a space that made it seem more possible that there was an audience for my sound.

There was this one performance I eventually did at a Pride of Arabia show — I wanted to embrace and highlight my femininity with an outfit referencing Haifa Wehbe. I’m so inspired by her as a performer and in terms of what she stood for: freedom. She’s one of those fierce women that stood the test of time despite getting shit in the media. Absolute icon.

At the show, I opened with "Ya Tayeb" by Angham, which I used to sing to my mum when I was younger, then I followed with a muwashah —partly because that’s what I’d gone to Lebanon to learn, but partly as a way of preserving the artform. I also sang an original song that I had written, an acapella. I remember feeling so loved and so supported as an artist; people were surprised, singing along, hugging me. That’s what encouraged me to move to Egypt.

I feel like we’ve both come so far since meeting in Cairo. What were you thinking or hoping that the city would bring, when you first made the move?

I remember I’d gathered a list of people to reach out to before arriving but had no idea what I was doing at the time. I just knew that I had some songs, I wanted to meet producers — three months and then I’m out. That three months turned into two years.

How do you feel that being in Egypt has shaped your sound?

So many ways! I’ve been lucky enough to take Oud classes with Hazem Shaheen, one of the most prominent independent artists in the Arab world, and I’ve attended Sufi zar performances…. I’ve also been practicing Tagweed and Talawat (learning the maqam through Sheikhs reading the Quran). I always wanted to take this and embed it into my own music.

I’d also say being here has guided my interest in music for healing. I took up classes with Mohammed Antar, an Egyptian ney (flute) player and specialist in the maqam tuning system, where we went through each of the different maqams. The approach was also from a spiritual healing perspective: what sensation or emotion does each maqam evoke? That resonated with me. I always talk of music being very emotional, deep, raw. A lot of the songs I’ve written are about heartbreak and abandonment.

Is that where the interest in maqams stems from?

Yeah. I always say that I want my music and performances to offer an opportunity for people not to be ashamed of feeling sad, or vulnerable, or angry, and to sit with those emotions instead. To offer an optimism within music and find strength in that. I feel like in today’s world we need more of the things that ground us.

So I was drawn to the maqams because I wanted to explore how certain sounds could evoke certain emotions. I’ve been researching Arabic, Turkish and Persian maqam systems, and I’ve noticed the western twelve temperaments scale is so limited in comparison.

At the traditional music events, classes, and sessions you’ve attended in Cairo, the spaces also tend to be quite socially traditional and conservative, right?

Definitely.

What’s that been like?

What was challenging about meeting people in those spaces was that I always didn’t feel 100% comfortable or safe, but those were the spaces I needed to be in to get the musical insights I was looking for. I had to do a lot of compromising.

What’s been the biggest challenge?

I’d say financing everything has been a big limitation, as someone from a working class background. Finding funding bodies that offer support, getting into the studio…Y’all out there if you’re reading this, Venmo me!

Period! Send the dollar this way. But yeah, that can be the biggest barrier to getting things off the ground. Other than that, do you feel that Cairo lends itself well to music-making?

Yes for a lot of the experiences I mentioned above, but there are still gaps that create a struggle for artists. Spaces to perform and jam in the city are limited. It’s been hard to find other musicians to collaborate with and just make music! I love watching other musicians in action and witnessing the process of making music.

Finding the right producer to work with was also a struggle.

How come?

Most of them wanted to create this fusion of Arabic music embedded into western composition, but I wanted to highlight the maqam systems in my music and sing in Arabic. Producers I sent demos to were like, “This is great, we love your voice, we could take it in an electronic, upbeat direction….” And I’d be like, “No, I want people to cry! I want people to focus on the oud, qanun, the ney.” I didn’t want a quick, 2 minute song. That’s not what I wanted to do.

What made Ahmed Diaa [the producer of your debut single] the right fit?

With a lot of the other producers, I’d been struggling to find someone I felt comfortable and safe with, you know, where I wouldn’t need to minimize myself and could have creative control. With Ahmed, the first time we met up, we sat for a bit and chilled, and I met his fiancé, which was a nice ice breaker. It just felt really comfortable. He was very validating and positive.

Ahmed also has a sophisticated language around Arabic music and repertoire and understood the style I was going for. A lot of the producers I’d come across didn’t have the skill-set of highlighting maqams and transitions within Arabic pop music. I brought him a few tracks I’d prepared, then we narrowed it down to this track Aqd El Hob. Recording-wise, it was really smooth: he started putting chords on it, and I felt okay to tell him what I liked and didn’t like. He’s definitely someone I’d want to work with again.

Tell me more about Aqd El Hob.

I wrote Aqd El Hob (“Contract of love”) a few years ago in London. It’s about someone I was with, and things didn’t end in the best way… The song is about not being afraid of telling someone that you love them even if that feeling is or isn’t reciprocated. Being honest and vulnerable despite the outcome.

Instrumentally, I try to follow the takht. In Arabic music, the four main instruments that you perform with are the ney (flute), the qanun, the kamanja (violin), and the riq (like a tambourine) and the darabukkah (percussion). I wanted more strings than percussion on this track.

I feel like it’s a good introduction: it sets the scene for the themes I’ll be talking about in my EP, and it’s raw and concise. I wanted to write in a literal and simple way, directly from my experience without it being super cringe.

Excited for it to be released. You’ve got such a beautiful voice.

Thank you! Yeah, I’m excited to release it and see how it’ll be received, see it build an audience receptive to this sound. Also hoping it resonates with other musicians and producers for future collaborations.

On that foreign beach in Spain, El Perro Del Mar was born — the alter ego of Sarah Assbring, dark, dynamic, and a liberating enigma that has spanned over two decades. This artistic endeavor has carried her to international recognition through world tours and, as of February 16th, 2024, to her eighth studio album — Big Anonymous. However, the artist's personal odyssey, in tandem with El Perro Del Mar, might be considered an even greater feat.

Assbring exists in an industry which no longer seems to cater exclusively to her kind of venture. I prefer not to simply label her among other musicians. It's not that her craft doesn't embody music, but rather because — in an era broadening not just who can create but how creation is perceived — her sonic landscape transcends the confines of traditional music.

To make music has become an endeavor too worn, the model too depleted, cluttered with empty clickbait titles and transient TikTok tunes — appearances devoid of essence. Assbring's sound, in contrast, is essence embodied. Thus, El Perro del Mar is an artist who, like those creatives truly deserving of the title, sees no form of expression as urgent as their chosen medium. For Assbring, that medium is her soundscape.

With Big Anonymous, an album of ten tracks originally composed for a performance at Stockholm's Royal Dramatic Theatre, she extends an invitation to us. Not merely into the realm of El Perro Del Mar, nor solely into the world of Sarah Assbring, but into the depths of ourselves. Through "dialogues with the dead," reflections on morality and mortality, manifestations of guilt and grief, and searches for harmony and honesty, she hands us the keys to our own internal portal. But she won't open it for us — that task is ours alone to undertake.

How is Stockholm these days?

Really dark and cold. This winter has been mega bleak.

As all of the Scandinavian winters tend to be…

Right. But for some reason this one has been extra heavy. And schizophrenic.

I’ve been hearing about that, from my grandma. She’s the only one I’m talking to from back home. And the weather is the only thing that's happening in her life. Perhaps the winter feels extra dark this year in regards to the world?

Definitely. You wake up and it's dark outside. You open the newspaper, and suddenly it’s dark inside as well. It’s immersive.

A dark place is a good place to be anonymous, one can lurk in the shadows. Would you tell us about the name of the album – Big Anonymous – if that doesn't completely contradict the concept behind it, expose it, that is…

It’s always about intuition I think, and this title came to me immediately once I started working with the material. Once something finds its way to you so early on in the process, it usually means that it's something you should stay true to.

In regards to the theme of the album itself, it deals with a lot of abstractions — not only death, not only grief, but a plentitude of depths, and so the title is my way of trying to embody everything that goes behind it. Yet it still feels too big to comprehend or put a label on.

I read it as the fear of becoming anonymous after our own passing.

In my experience, it applies equally to the people that I’ve lost — the fact that they’re eventually becoming anonymous, which is such a terrible thing–but also, as you mentioned, when you grasp the fact that eventually death, and therefore anonymity, is coming for you, too.

At the same time, at least outspokenly, a lot of people cry out for “anonymity,” today, wishing there was a way to delete the data. Do you think that “to be anonymous” holds value?

That’s a different type of anonymity. What the album expresses is rather this endless enigma, the “nothing-but” anonymity; the fact that that’s eventually all there is. It’s about existential nothingness, really.

Which can be such a liberating force, too. I mean ask Sartre, he’s the one who told me. Have you made peace with the idea of death?

I have understood that there is no life without death, and thereby, finally, been able to acknowledge that likewise there’s no death without life.

That’s it. Pretty sure you just put the whole soundscape down in words.

The album, while being very melancholic, simultaneously puts you in such a state of relief. Kiss of Death certainly feels like a good sonic example of such — starts of hunting, terrifying, but when the presence of death finally catches up with you, it's no longer scary, it's not a stab in the back: it's a kiss. Reminiscent of how meaninglessness is being addressed in existential philosophy.

That's a nice note. Doing this album has been such an important journey for me, and Kiss of Death was really the final destination. I was coming to terms with feelings of grief and guilt and fully accepting, almost embracing, my own ceasing. I realized that I can’t change any of the things or traumas I’ve been through, however, I am fully capable of changing my perception and perspective of them.

I have this mark on me, now I choose to see it as something beautiful. I can choose the stance of having loved and having felt love for the people that are now gone. And me remembering them is also proof of love. It boils down to perception–possibly cultural values as well–and rethinking requires that we let go of our fear. We should aim to be brave enough to question what events should be attached to what emotions.

How did you let go of your fear?

Writing this album provided me with a tool, something to carve with. I think of it as poetry, and it’s been a healing process; a way to understand myself on a spectrum I haven’t quite dared to explore before. Until I wrote this album, that is.

On a non-conventional level? It takes some, several detours to realize that even language — what we use to understand our selves — are just generalizations, thus to go deep we need to go beyond words.

That goes for how we’re told to treat or react to death as well. I can only truly speak of the Western, Scandinavian perspective, where we really have furthered ourselves from the idea of death. That creates some tangled agonies, some of which probably won’t come back to haunt you until later in life, which seems fine, but later, once they do, we’re not sure what they are or how to deal with them. It’s weird. But that's what and why I want to talk about–what I would like this album to navigate through–emotions of grief, guilt.

That’s a therapeutic approach: the methods of sound. Sound transcends words, and therefore puts us in closer contact with truth, at least according to Nietzsche, or perhaps I’m just damaged by professor Dodd. But let’s talk about guilt for a second, I read that you felt guilty for being alive while others aren’t?

I did. But then I finally asked myself the right questions, even though they came at the wrong time. By writing these “constructed dialogues”, the lyrics, I was able to transcend into a place of being forgiven. It's very frightening to be vulnerable, but once you reach a certain point where you start dreaming about things, having nightmares, waking up to the feeling of being haunted, then you have to deal with what might have felt impossible at first.

I’m not trying to make it sound easy, I mean it's very frightening to be vulnerable, but once you reach a certain point where you start dreaming about things, having nightmares, waking up to the feeling of being haunted, then you have to deal with what might have felt impossible at first.

Looking outside of yourself can really help as well. I mean everybody has, or has had, experiences with “darker,” feelings, whatever that really implies. What I find interesting is how we so rarely touch upon them, it’s like we’re all so afraid that we’re going to bring up bad memories,

“Weigh down the mood?”

— exactly. And so we stop talking about them, pretending like they don’t exist, arguing that “the word is already so heavy,” without realizing that when we suppress these emotions we’re actually adding weight, as opposed to once we dare to talk about them, that's when weight is released. It's almost illogical. But I believe that it’s important to keep asking questions without finding a definite answer.

In short, it's been a very personal intimate journey, but at the same time, it's also been a very social, bonding, experience.

What about that experience? Tell us about what it was like to create music for a performative setting like Dramaten [The Royal Dramatic Theater].

I was freely commissioned, permitted to do whatever I wanted to, and it certainly felt like the right time, and the absolut perfect place. Dramated being a stage for spoken drama, I approached the project as a performance rather than “I’m going to make an album and put on a concert.” So performance became the starting point, which is obviously very different from how I usually create, this allowed the music to go places it never could have reached if it weren't for the idea of stage.

In the studio it's just the microphone and you, what's the main ingredient when you compose for a performance?

Movement, sound, choreography, lyrics–I’m pretty sure I had all of these factors equally considered in my mind, which probably sounds chaotic, but it wasn’t. I felt like I found a very natural place which allowed me to be filterless; the dancers, the stage and the design removed the pressure of me as the vocal point, which made it that much easier. I could be 100% personal and still make it nonpersonal.

The commission opened a different door to what felt like endless opportunities, but I think of the album that came out of it as a very separate thing. The performance was a performance, and the album is an entity in itself, it’s not stage music, even though they’re both rather melancholic.

What about it?

Well, I'm very drawn to melancholy. I think it is a big part of me, always has been, and is always going to be. The type of melancholy that does not leave you feeling low, but leaves you feeling thankful, blessed about having feelings, just emotionally richer. That’s the ambition of the album; to embrace the emotions of life. Saying that out loud makes it sound cheesy…

The quote in itself sounds corny, indeed, but once put in relation to your tracks it becomes something completely different. I think when people want to celebrate life they usually plug in, I don't know, Stayin’ Alive with Bee Gees?

That’s just me. I would never, ever, cheer myself up with “happy music.” It just doesn't work. It's what it is. I'm the kind of person who prefers to watch a horror movie instead of a comedy to make myself feel better.

Because on some level the horror feels more honest?

Because I like to be shaken up a little. Every now and then I tend to go too much, and perhaps too far, into the darkness of existence, and then the horror is a great way for me to wake myself up, to realize “what the fuck! you have this beautiful life, and it's right in front of you, and it's happening right now... and eventually it is going to come to an end, even for you, my dear…”

Better get out there and celebrate. Are you a believer in the afterlife?

I am not.

What about the film, you’ve been in music since 03 but this is your debut in terms of working with visuals, does it function as an extension of the Dramaten performance? The performance-the album-the film: the non religious holy trinity?

My desire to film goes way back, but the performance in 2019 opened the door, then it slowly progressed from there. I work closely with my stylist, who's also an art director, Nicole Walker, she also played a key role at Dramaten. Once the performance was done and the album recorded, she and I discussed what it would be like to push the project further, it got us both excited about doing a film. A movie felt like the right medium, and she sure is the right partner – the one you don't have to say more than a few words to, for she already understands your vision.

We wanted to find a way to make the viewers uncomfortable, to go places one usually avoids, consciously put pressure on where it hurts. And to me, doing that means going via horror.

I don't feel like you’re the type of artist who sends people off to the uncomfortable for the sake of being uncomfortable, but rather “I want you to discover something of yourself, please go dwell in this feeling and see where it brings you.”

Exactly. It's not for the entertainment of being horrific. The movie is supposed to be an equally therapeutic experience.

You mentioned earlier that you carry this mark on you, whereas in the film, one of my favorite sequences is when we see you biting yourself in the arm, again and again — is there any chance these two have a resemblance?

Exactly, that's the mark. It symbolizes one of my most vivid childhood memories. I was at a funeral, probably my first one ever, around five-six years old, finding it so difficult when looking at all of the adults around me who were really holding it together in order to not cry. It was such a bizarre scene to my childhood eyes. I remember finding their behavior so strange and foreign, but still I did the same – I swallowed my tears and left feeling affectionate and sincerely sad. My first reaction to keep it together that day was to bite myself in the arm. I did so almost unconsciously, but it stopped the tears.

Today, I view the mark as a symbolic translation of our modern day -disease, the result of an innocent child’s behavior who naively adopts the pattern of her surroundings, while our social environment leaves us feeling rather numb. It's no longer common to give ourselves time for grief, we diminish our minds – it's a scary path.

One that we can wake up from if we dare to acknowledge its existence? If so, I’m planning on dwelling in it, on 28th of March, at ca 8PM, on 233 Butler Street, New York, to be exact.

It’s going to be so special to see people perceive the album live. Maybe we can meet up when I'm in New York.

Tickets on you? Red wine on me.

His latest release, “Radio,” is sung like a confession, and compared to the rest of his discography, it’s pretty stripped down. With lyrics like “Almost seven days away from one week sober,” and “I never needed you, please come over,” “Radio” is his most vulnerable song to date — and maybe not all we'll be seeing of him in the near future. We sat down with Malice K to talk about Vegas, furries, and how much he likes doing interviews.

The first time I speak to Alex, he asks if I’m from New York, and I’m a bit of an asshole so I make him guess. He guesses Canada, and I ask if there’s anything about me that feels particularly Canadian. He says it was one guess that was as good as any. I tell him I’m from Ohio.

Alexander Konschuh— I like Ohio — you guys all eat white bread, it’s great.

office— And you’re from Olympia? How’s that? Did that have any impact on how you make music?

Definitely. There’s a lot of music history and culture from there, but you can’t really build a career as a musician there. I mean, you can be a musician and figure it out, but it’s not like New York, where there are a lot of investors or labels or music venues where you can play and make your own way. When I was growing up, I was just around a lot of people who liked to play, and they were just obsessed with music because they were musicians.

But there wasn’t anybody that had an alter ego or stage name or anything. It was all pretty laid back. And that was pretty lame. It took me a long time to feel comfortable pursuing a musical career and having an alter ego and stuff, because growing up, it was pretty shunned. Everyone would be like, “I just play, man” [laughs] But I got a lot of time to just learn and appreciate music, playing without having any aspirations of it becoming something. I think a lot of people will move to New York or LA with this aspiration of becoming this musician-person. And they start there rather than just figuring out how they play.

I read Carrie Brownstein’s biography, and she was talking about Olympia being the place to be for musicians, but she was also a different type of musician than you.

And that was a couple of generations back for me. But it’s true, in a sense. I got the leftovers from that era — a lot of house shows and house venues, but no bar venues or anything, just different houses all over Olympia. And so many bands loved coming through Olympia because they’d get to play these really fun house shows. Being a musician, it’s a good place to be, but trying to make money or have a career as a musician, that’s a different story.

How’d you come up with “Malice K?”

I was a teenager doing some traveling with some friends and we were in Arizona or somewhere in the desert. And everybody was giving each other nicknames, but nobody game me one [laughs] So I had to just pick my own. I was wearing this poncho the whole time — it was the only outfit I wore that whole trip. And my last name is Konschuh, which kind of rhymes with “poncho,” and Alex sort of rhymes with “malice,” so I was Malice Poncho for a while. There was a weird couple-year period where everyone just called me Poncho because of that. But when I decided to put out music, I just changed the poncho part to “K.”

What brought you to the desert?

I wasn’t really going to high school anymore, so it was just something to do. All of my friends were driving down there, they had a roommate that ran away, and they were going to retrieve her from Las Vegas, so I went and it was really fun. She actually didn’t want to come back, but I got some good partying in — tried the slot machine, won like, five cents [laughs]

We had to ask for gas the whole way there, because nobody had any money. We had to go and ask people for five bucks or gas, I didn’t know it was going to be like that at all. But my friends picked me and this other guy’s girlfriend to be a pretend couple, because I was the most trustworthy, or we were the least disarming or least scary-looking. I think they thought, if we were the ones asking, it wouldn’t be an immediate “no.” Maybe they had an eye for those things, because we did make it to Vegas.

Did you have a musical upbringing?

Yeah, my parents were always really interested in music. They cared about it a lot. And I was kind of surprised — my parents were pretty well-educated, but they were teenage parents and stuff, and their backgrounds made it a really cool and rare thing. I had such cool and knowledgeable parents, they always had art books and biographies everywhere, and this huge box of CDs that I would go through and listen to.

They really liked the music that I liked. Growing up with young parents, we’d all be listening to the same music in the car, and they’d be into it. So I was always around music and being influenced by it. And I started playing drums when I was in elementary school, and I’d play at my talent shows or whatever — just solo drums. And then, there was this jazz bar that did open mic nights where we’d go and play. But everything else that I know how to play now, I just kind of taught myself throughout the years. And then one day it all just came together, and I was like, “Well, I should start making songs.”

That’s how it happens. What made you come to New York?

I got a phone call from this record label out here, they were inviting me to try them out, see what they’re about. And I was living in LA before I came here, doing music stuff with this group called Death Proof Inc., which was this artist collective down there. I started the Malice K thing over there. I was building it and then it just got some label attention over here. I’d lost my place in LA while I was visiting Washington but I got a phone call to come visit New York. So I just came out here and figured out how to stay and make it work. And here I am.

When was this?

Recent — around two and a half years ago. I came right when things were opening up again. It was fucking insane [laughs] Every day was like a movie, the most psychotic movie you’ve ever seen. Everybody was out. It felt like the sixties or something. Everyone had kind of acclimated to this life of not working and getting money and drinking every day. So when everyone came out, that’s all you were doing. It was just one big party for months. It was a great time to move.

So “Radio,” your newest single. Break it down for me.

Break it down? It’s a song, and I wrote it, and it’s about feeling hopelessly yourself, and that there’s nothing you can do about it. I assume this is normal for other people, but in my life, I feel that I’m always trying to become something better, or be a better version of myself all the time. And sometimes that’s not necessarily a good thing, and that the things that are your problems are a big part of who you are. Sometimes, wishing that you were better, wanting to be different in a way, it’s kind of not honoring how strange or particular you are as a person.

It’s like, you are yourself, even if that conception of you includes parts you might not like, at least in this present moment. Or am I misinterpreting it?

No, that’s a fair interpretation for sure. When I first came here, and when I first started having fans or people who were looking at me in a certain light, I did a lot of stupid shit. I’d do a show or something, and then I’d just hang out with everyone that came to see the show and get super involved, but it became this whole thing. Being admired, or having to be too familiar with someone too quickly — there was always something about the whole ordeal that made me kind of sick. But I would ignore it because I figured I just needed to get better at that, and that I just needed to learn to enjoy having fans because I’m so lucky to have something like that. And I didn’t realize that I was kind of disrespecting myself, because there’s really no need to try and put myself into that box. That’s what the song’s about — the discomfort that comes with trying to overextend yourself or trying to be outside your comfort zone.

That makes sense. I don’t think we have time to get into parasocial relationships, but people treat you differently. Do you think that separating Malice K from Alex helps you deal with those weird attachments?

I don’t know. I’ve taken a lot of personal distance away from things. I’m trying to create a healthy relationship between what I’m doing and how I’m doing it. Before, I was trying to be at all the parties, trying to have a physical presence and be a full-time performer. And it would work, in terms of people’s engagement or getting attention and stuff like that. But then my work ethic and stuff fell with that, because I couldn’t keep up with going out all the time while also exploring myself and being present with where I’m at in my life. But, as soon as I stepped away from doing that, I saw a huge drop in engagement. And that kind of hurt me a bit, but I’m getting over it.

I’m just not taking all these pictures anymore, and I’m not going out to this party or whatever, so I don’t really have anything to say or post, except for if I drew a picture or if I’m working on a song. I just stopped posting that often. I didn’t post for like, a month, and in that time, my monthly listeners on Spotify dropped by more than half. It dropped forty-something thousand people, who all just stopped listening to what I was doing because I wasn’t keeping my social media presence.

It’s scary how much the Instagram algorithm works, and how the people who are listening to your stuff have to be reminded that you exist.

It’s coming at us so fast.

And there’s a new singer-songwriter every ten minutes.

And Instagram just expects you to compete, which is insane, because it’s not even a music platform. It’s not a platform for anything, it’s just everything at the same time. I just don’t have enough to say for you to think about me in the midst of the million other things happening. And I don’t want to be like, “Oh, I’m eating this” or “I’m doing this” or whatever. Because my Instagram is my portfolio — it’s my website, basically. It’s for what I’ve done and what’s on the way.

If I don’t have anything to say, why would I say something? It feels kind of insane. It’s almost impossible. I’m getting to a point where whatever happens, happens, I guess.

And that’s a healthy distance to maintain because social media is unpredictable.

And they totally censor you. It’s not even a demographic platform — you can’t even consent to what you engage with at all. I’ll post a drawing or something on my story and it’ll get maybe 200 views. And I’m just like, “I’m gonna try something,” and I post a selfie and it gets 2000 views. And I’m just like, “Yo, you just censored my artwork because it didn’t match this algorithmically detected aesthetic that will keep people on the app longer or make them feel a certain way.” What am I going to do? Become an Instagram influencer / model / music, which will definitely jeopardize the other thing that I’m doing? So it’s just like, if you know about me, you know about me and what the fuck ever, it’s not my goddamn problem.

That’s a good way to look at it, because so many people get annoying about trying to establish themselves. Which is fine if that’s the game you wanna play, but a lot of people put themselves in compromising positions just to get clouted.

I’m just trying to invest in my actual future, like Weezer — that’s a band that I would still see. There’s something about them. They just maintained a certain aura about them, like the Pixies. I just think the things you say “no” to are a way bigger investment in the future than just saying “yes” to the demand of the time that you live in. Because someone could be like, “Oh, there’s that really awesome dude. He painted all that stuff, it was really cool.” Or, they could be like, “Oh wait, that’s the guy that’s — I don’t know — the face of Honda” [laughs] Maybe saying “no” to that one thing oculd be a really big investment in your future that’ll end with a napkin you drew on getting into a museum because you didn’t make yourself look like an idiot in a Honda commercial.

Is this you trying to ask for a Honda sponsorship?

I wouldn’t even finish the email, I’d just say yes immediately [laughs]

I’ll pull some strings, send the director of Honda a magazine maybe.

What have you been into lately?

What have I been into? Doing interviews [laughs] I’m just thinking, “Where have I even been? What is there going on?” I’ve just been really into doing interviews, they’re fun. And it’s been feeling good for me to do, because I’m at a point now where I’m just saying things how I would say normally, instead of saying things how I think a musician would say. You know what I mean? I think I have less of an identity wrapped up in what it means to be an artist or a musician. When I first started doing interviews, I’d be nervous, because I’d be thinking, “What if I don’t come across as a musician?” — all this weird existential stuff. But now, I’m at a more comfortable place in my artistic career to where I’m letting go of things like that. And it feels good to talk about myself and be more transparent, more sincere.

I get that, because for a lot of musicians, they have this persona they put out, and if they were all to do interviews as that persona and not let people see their actual selves, it would get really boring, because we wouldn’t be getting anything that we didn’t already see. You know what I mean?

Totally. And there’s a lot of musicians and a lot of things that I’ve felt really loyal to. And I was really enamored with them before coming here and doing what I’ve been doing. But now, I guess I realize how much business sense you have to have. A lot of these artists that I’ve admired, I’ve realized that they made a lot of business decisions and weren’t total psychos, which is so much of the persona of the artist — that’s the way to sell it, because it’s a business made off of the image of this one person that goes to publications or whatever. And I started seeing that once I started treating music more like a job. Once I stopped romanticizing this idea of the artist, felt like it freed me up to do things the way I’m doing them instead of thinking of music like, “Oh, I’m entering this atmosphere,” or “I’m among these types of people.” I’m just alone and desperate and I don’t know what the fuck’s going on [laughs] I’m just trying to be here another year and I’m just making it work.

What's your writing process?

I’ll have a guitar part that I really like, and then I’ll just mumble whatever until I figure out the cadence I want the song to be in, and then I’ll figure out the melody and I’ll just fuck around with it and sometimes somethimgng will happen immediately. But for a lot of the songs I write, if I don’t write it in ten, maybe twenty minutes max, it usually won’t be a good song. Every time I pick up a guitar to play, I’m just trying to find the moment where that happens.

Because when I’m being honest and in a regular conversation, I’m not thinking about what I’m going to say, I’m just talking. And I think it’s music or art that does the same thing, that doesn’t happen often, but where you can just say whatever and have it fit and match the parameters of the melody and the structure of the wording that you want to use. It’s all about doing that every day until something happens, and then knowing when to move on so you don’t get bored.

I have a shit ton of different songs or half songs or quarter songs, or these riffs that I’ll just shuffle through. I’ll just pick up the guitar and go through everything that I have. And most of the time, nothing happens. Maybe once every couple months, I can be honest with myself and have it match a melody that feels catchy. Because I don’t have a band. It’s just me.

Did “Radio” happen in 10 minutes?

The lyrics did. It happened super fast and felt really good. I felt guilty about how honest I was being with myself, thinking, “I’m not supposed to say that,” [laughs] It was a really good feeling.

You’re a little nervous about putting something out because it feels like you’re naked in it.

Oh, that’s good. Yeah.

I hear you're playing a show in London?

Yeah, anybody can come to London. It’s a free show, zero dollars.

You just have to fly to London

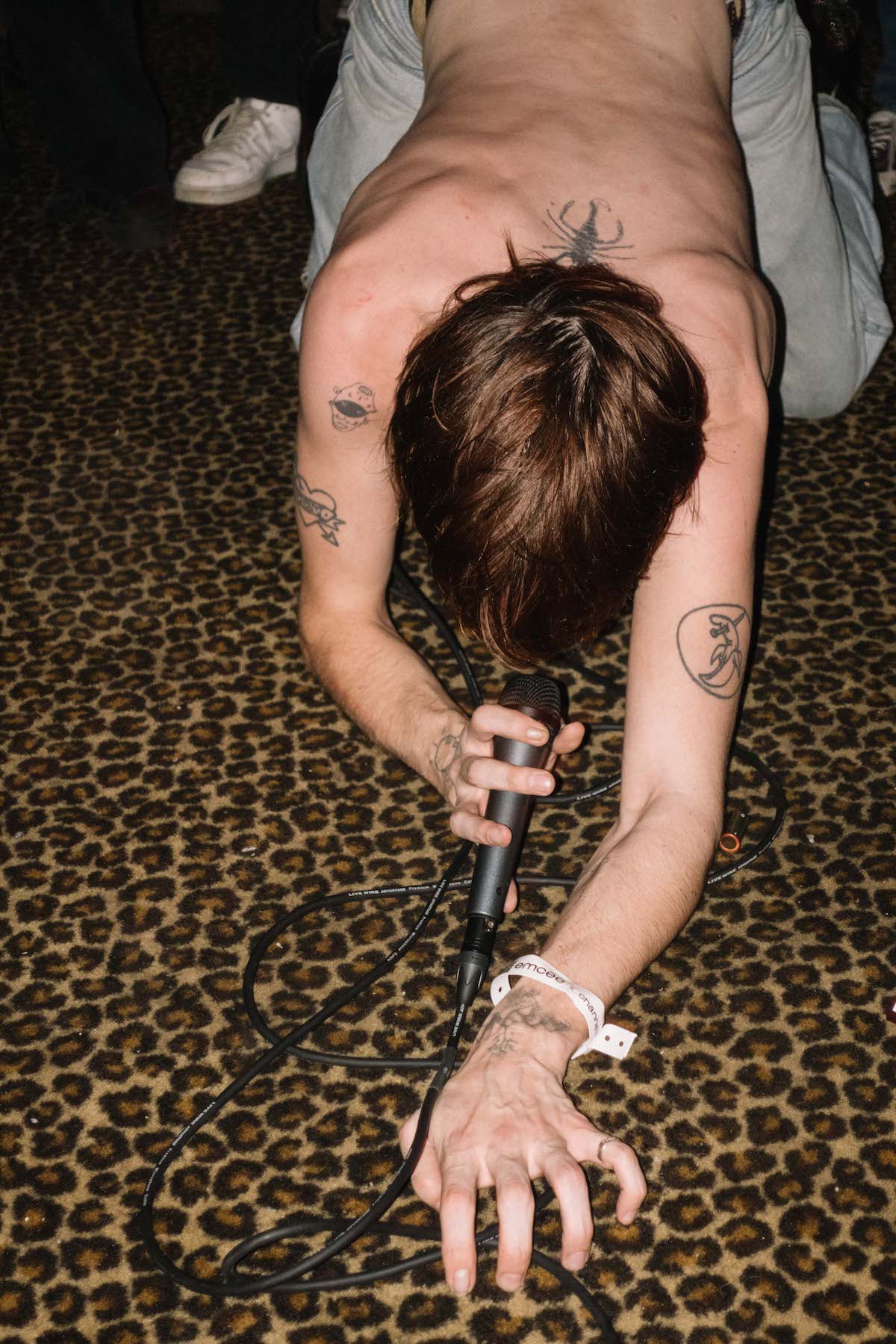

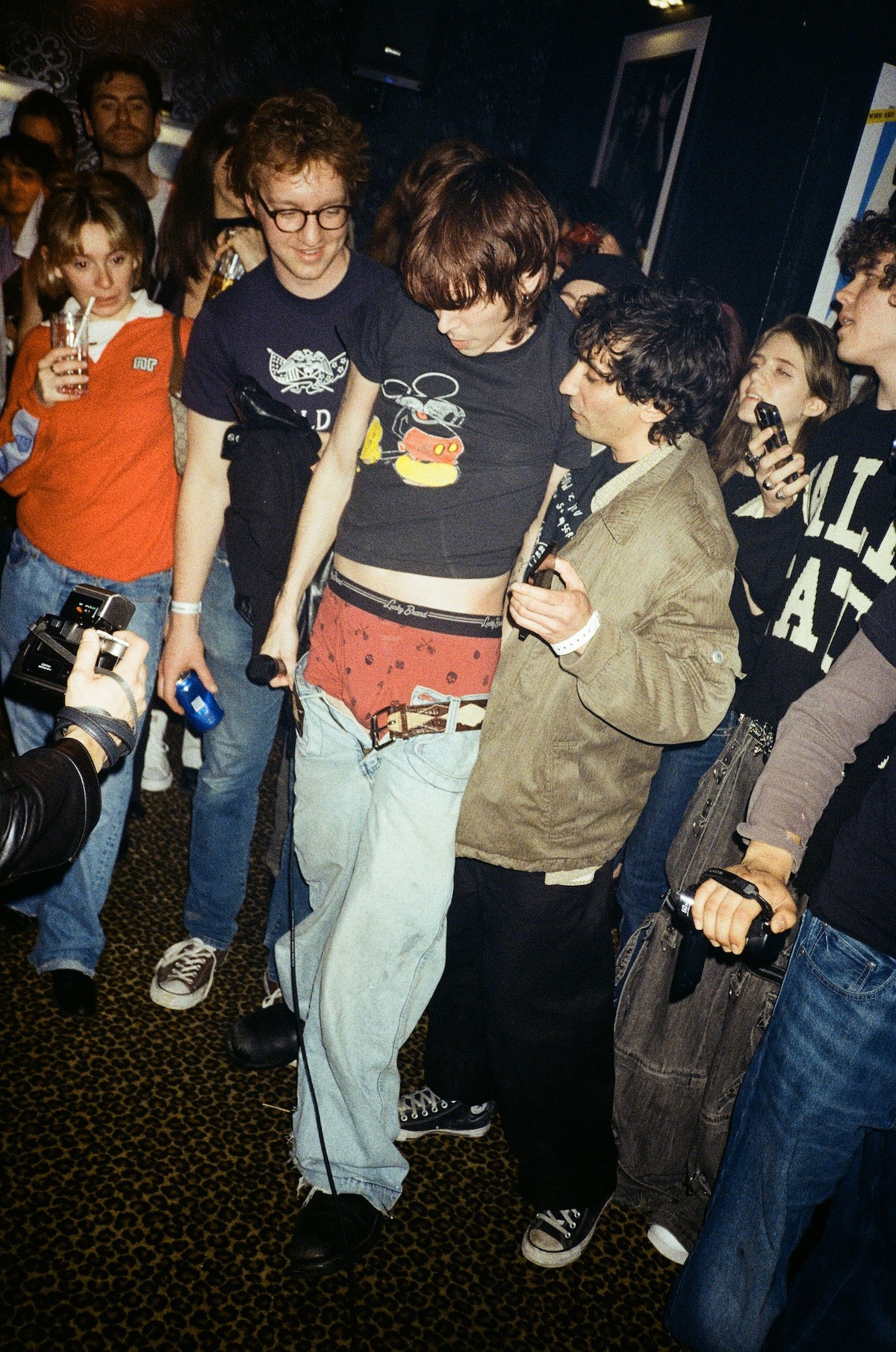

[laughs] Maybe this show is just for all the chaps and lasses. My show at Gonzo's was all-ages, so it was a little reckless. My teenage fans are grazy. They go hard.

Kids go crazy. Have you ever been to Trans Pecos?

Yeah.

Once I went and it ended up being this all-ages furry night. I didn’t even realize it was furry night, it was just called “Club Kitten” so I just thought it was a cute name about cats. And I was like, “Hell yeah, I love cats.” And then people showed up in tails and stuff and there were like, fourteen year-old furries there. You love cats, but they love cats. But was a fun night. The furries know how to party.

You’re like, “I didn’t even know this was what I wanted.” I mean, no judgement. I’m not a furry. If you are, you should go undercover for the magazine.

That’s ok. I am also not a furry. I just like Trans Pecos.

I’m gonna write a cross-article about furries in the workplace or something [laughs] but yeah. I got all these younger fans from when I was doing the Deathproof stuff. It was this modern kind of e-boy thing — a real Lil Peep kind of vibe. But they go super hard. The last time I did a New York show with the Deathproof people, I realized that this is probably where my fans are at, because everyone was singing the lyrics. And I couldn’t get off the stage for like, twenty minutes. I was just signing stuff, and I couldn’t stop signing stuff. People gave me their phones, their inhalers, all this stuff. And I was like, “I guess this is where I’m at now.”

So you’re making the show all-ages because you want more inhalers.

No! I didn’t keep them. I don’t want your inhalers.