Oscar yi Hou Sets Reality Center Stage

“My first show with James, I’d just graduated college and I was really interested in academia and theory,” yi Hou told me over Zoom. He was preparing to unveil The beat of life, and I was at my boyfriend’s mother’s home in Yuma, on a month-long road trip interviewing strangers before the election. It’s been a whirlwind much like yi Hou’s experience of 2021 and 2022, cranking out art.

“[Academia and theory] heavily informed my practice,” yi Hou told me. “They still do now. But, this was prior to having lived life as an independent adult. As the years passed since graduation, a lot of the theory that I was reading started to be less applicable and less relevant.” Days later, my colleague Dorian Batycka posted an IG story of a classical sculpture from Art Basel Paris with a similar idea: “The fact that no one can (or wants to) make this anymore points to a wider problem: that art has become so obsessed with concept/theory (and money) over basic form.”

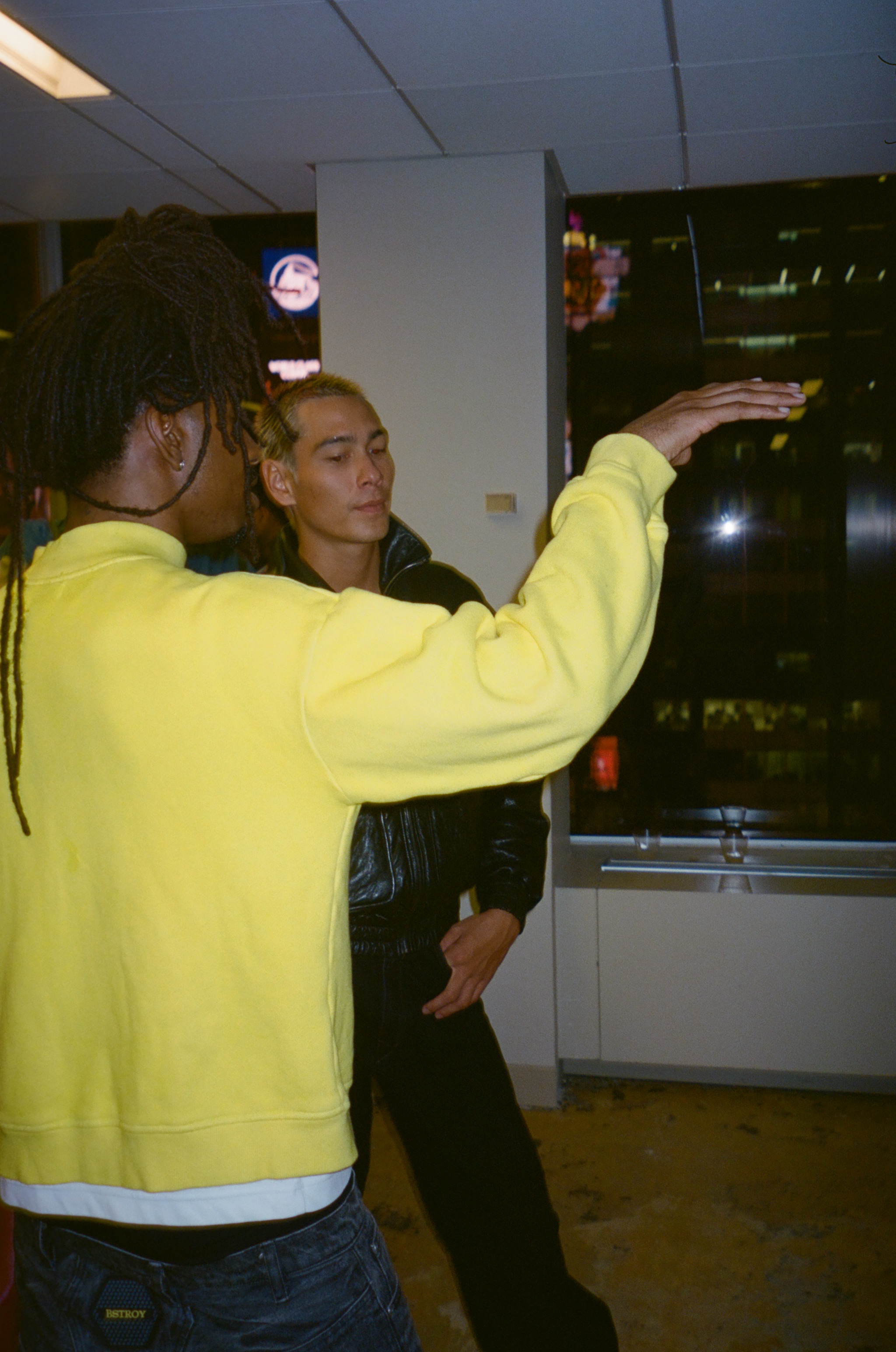

Thus, yi Hou is now drawing from daily existence — from “nightlife and putting myself out there,” he said. “Having a lot of sex with a lot of different people. At least for gay men or queer men, that is a great way to make friends.” The title of his new show once again draws from a poem he wrote. It evokes police violence and music alike by referencing the thrum of a heart in a chest.

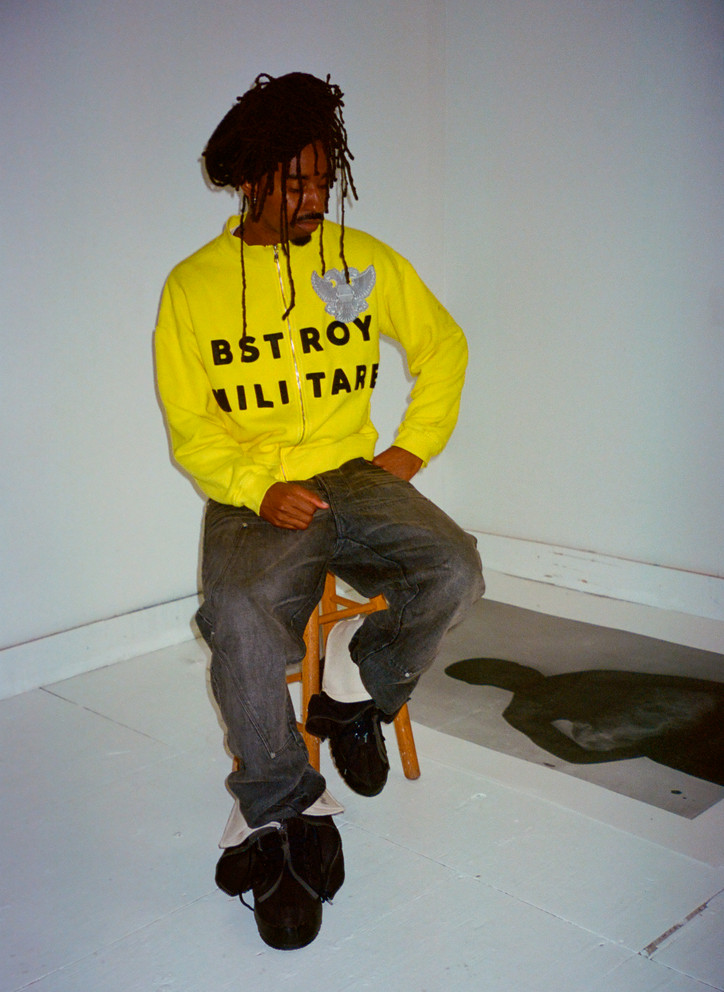

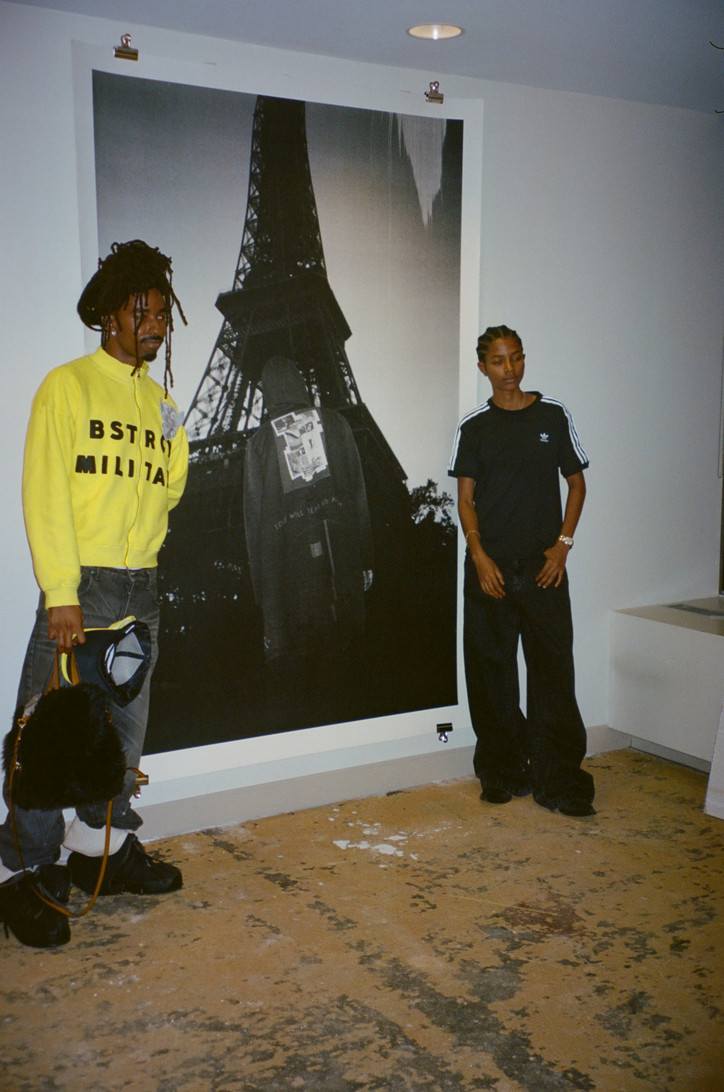

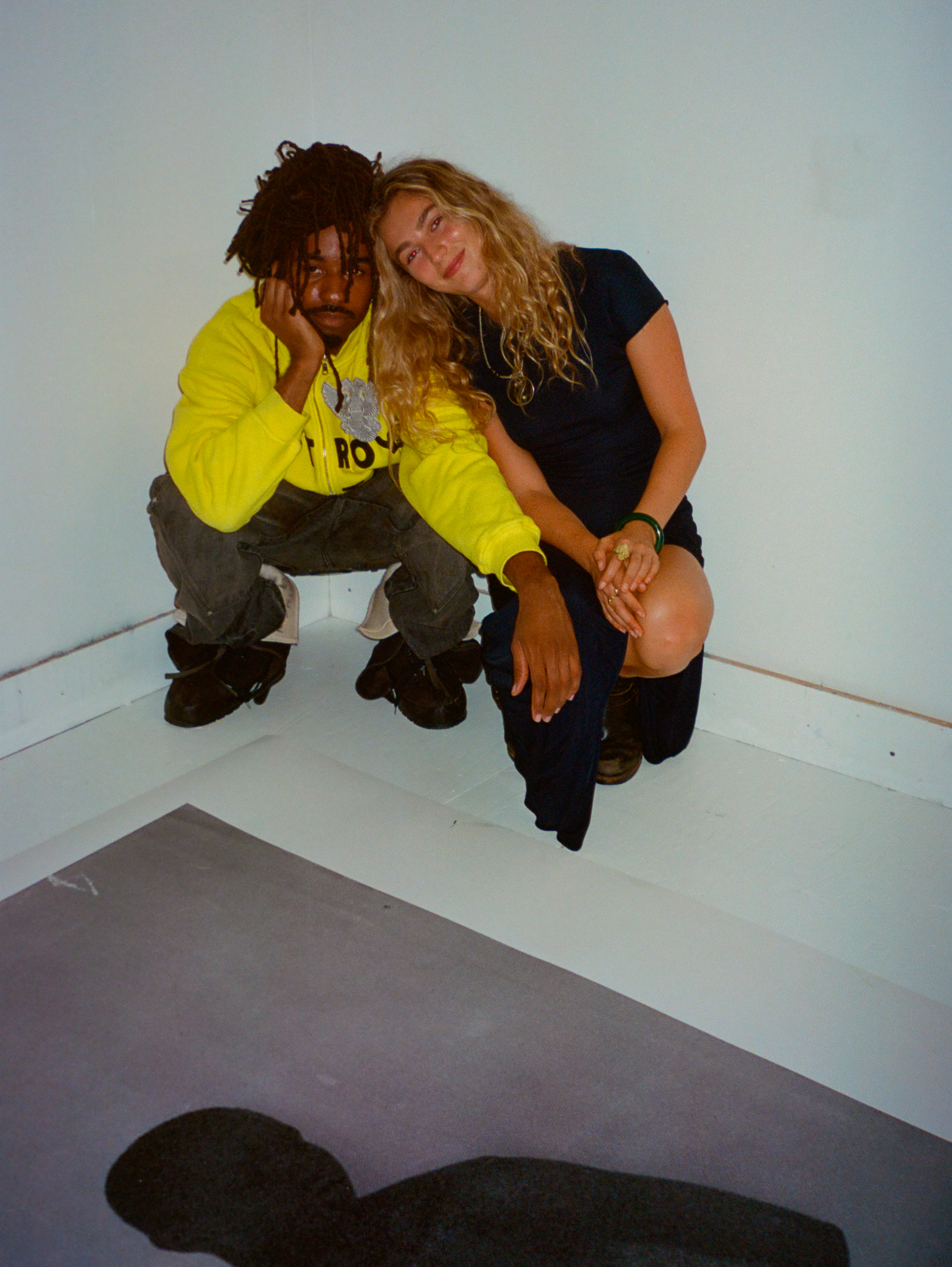

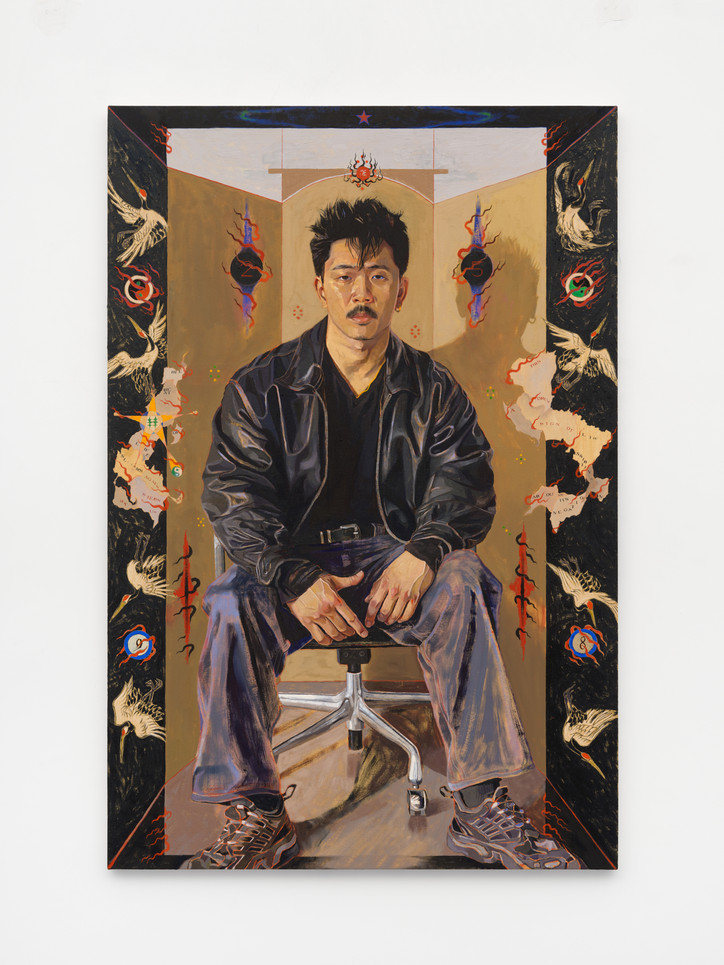

Birds of a Feather aka: Chinatown Gangsters, 2024.

The show itself simulates that sensation. For the first time, yi Hou presents several scales across The beat of life, which oscillates like a pulse between small, close-cropped busts of compatriots like yi Hou’s boyfriend, and larger arrangements like Birds of a Feather aka: Chinatown Gangsters (2024), which depicts yi Hou alongside artists Amanda Ba and Sasha Gordon. (Perhaps he’s angling for a Deitch show, too.) Across sizes, yi Hou amalgamates oils with gouache, graphite, and more. Yet, these works bear new marks of maturity, like the honesty of discerning one’s strengths and the power of saying less, a confident refusal to explain further.

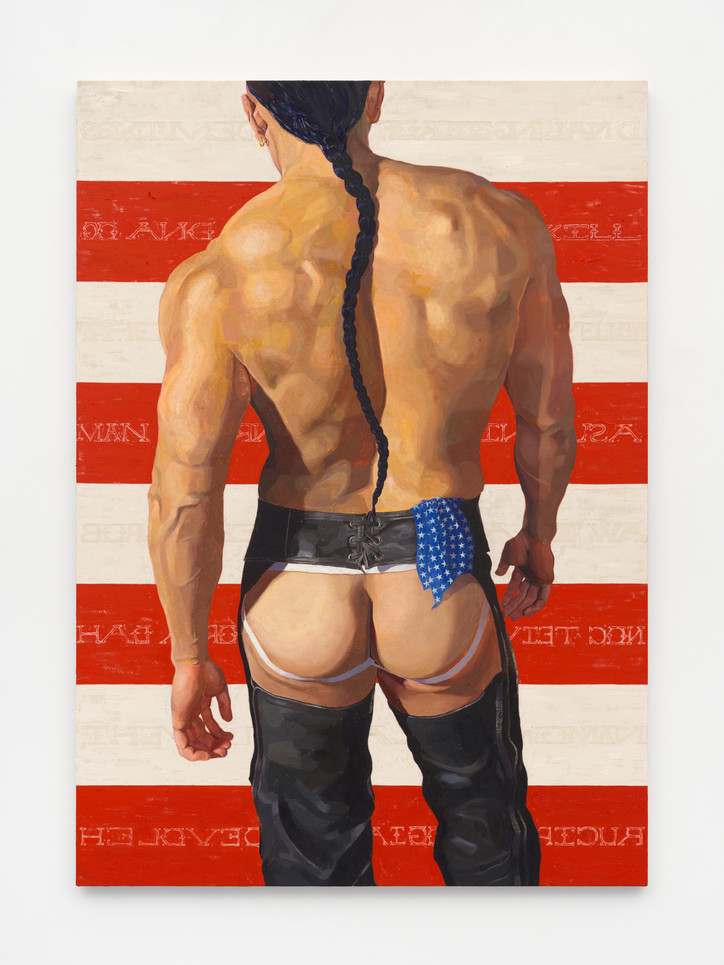

Orange and magenta still flash throughout yi Hou’s linework, but rather than sculpting figures from many maximalist flat blocks of color, yi Hou has spent time tenderly rendering flesh and fabric true to life. Supple cheeks exposed via rich assless chaps greet guests entering The beat of life from Coolieisms, aka: Born in the USA (Go and Kill the Yellow Man) (2023-24) — a painting named after Bruce Springsteen’s famous hit. Obama used the song to counter birther conspiracies, while Trump plays the pithy American critique patriotically at his rallies.

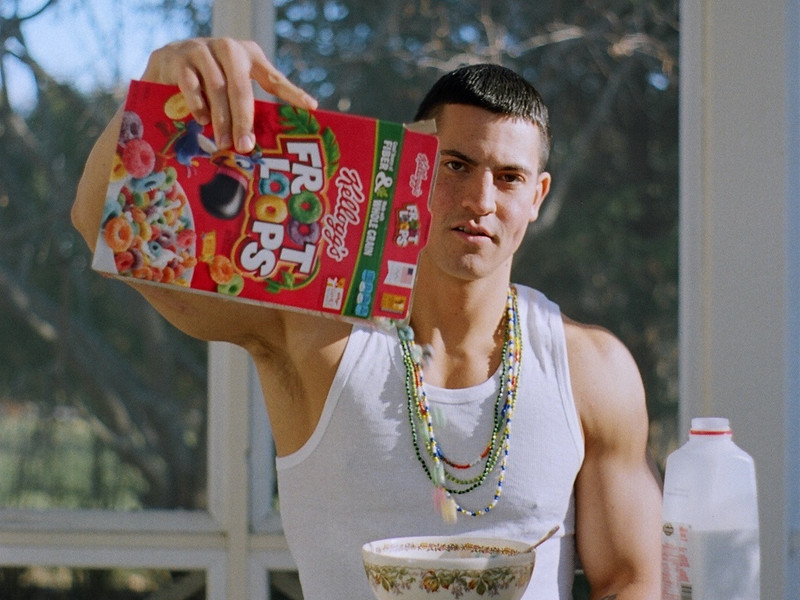

Coolieisms, aka: Born in the USA (Go and Kill the Yellow Man), 2023-2024.

This initial artwork hails from yi Hou’s ongoing Coolieisms series, which reclaims a 19th-century slur for exploited Chinese rail laborers by depicting Asian figures in the trappings of Americana.

“Was there a leather daddy back in the 1800s working in the mines?” yi Hou mused. “Probably not.” In Coolieisms, though, he uses his own visage and imagined characters to forge fictions that highlight stereotypes about Asianness, masculinity, heteronormative culture, and more.

Yi Hou has previously spoken about the paradox of representation, that newfound art world fixation. Representation isn’t necessarily action, but it’s necessary for an equitable society. “It can be a burden to think about these things, but it's also quite generative,” yi Hou added. Symbols carry historical meanings, while also offering canvases for each viewer’s projections. They’re ephemeral, but spark material impacts. There’s a chilling reality, after all, to rooms full of people singing “Go and kill the yellow man,” regardless of which politician might be playing it.

The Coolieisms series was once the one place yi Hou exercised license. “I was interested in the ethics of portraiture and trying to not commit any symbolic violence to another person through a painting,” he recalled. “As I got older, I was like, ‘wait, none of my sitters give a shit about that.’”

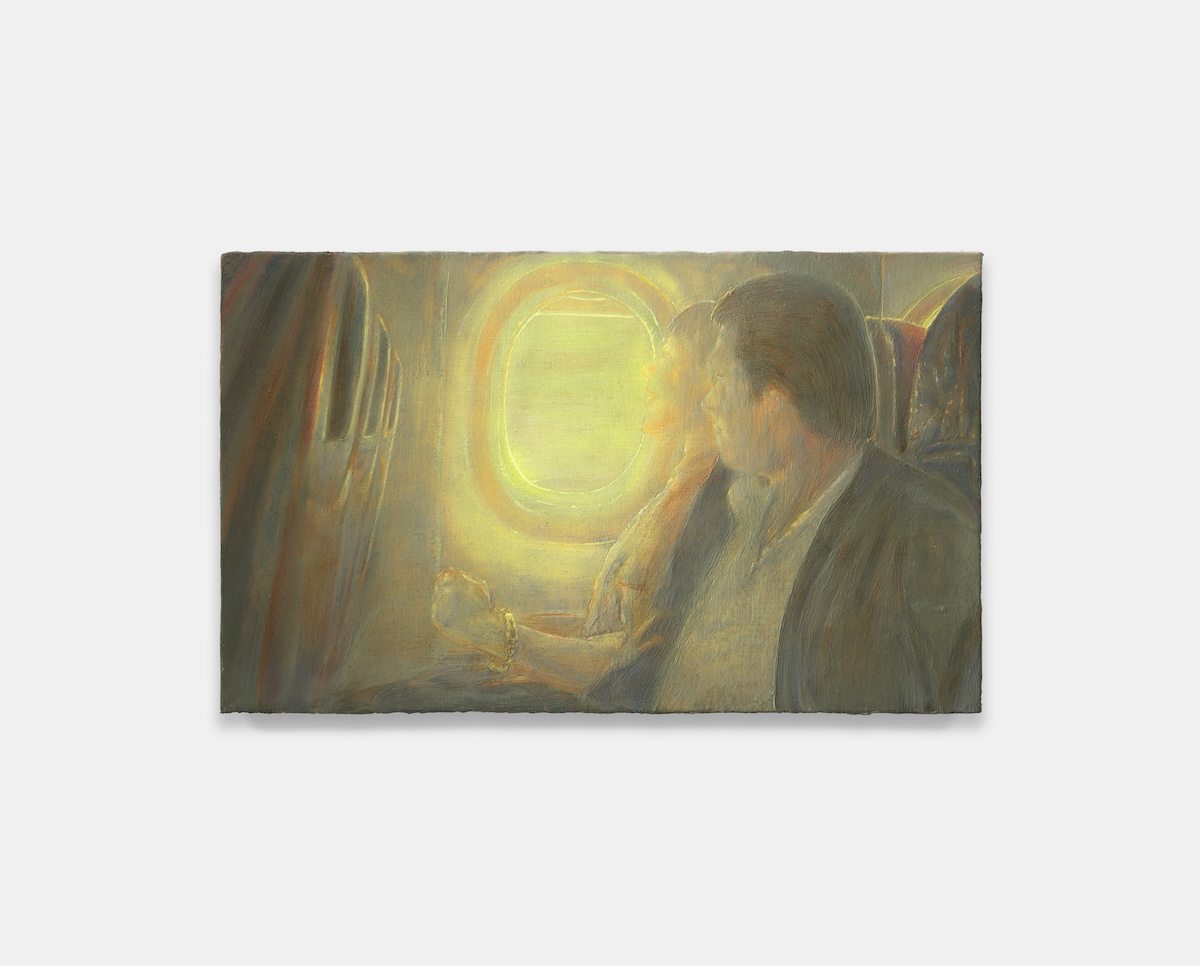

Symbols offered a sort of camouflage that enhanced while encrypting meaning. They’re active here, too. Yi Hou’s use of the color wheel proves somewhat new, but he’s harnessed sheriff’s stars and yin-yang signs before. “I've been interested in opacity and obscurity, generating mystery or opacity through these symbols,” he said of his compositions. “Because I've talked so much about them, they're a bit transparent now.” In another interview, yi Hou noted that sometimes indirect communications convey more. Thus, he’s set such icons ablaze in works like Self-portrait (25), aka: The beat of life (2024), “to further obfuscate the meaning behind them.”

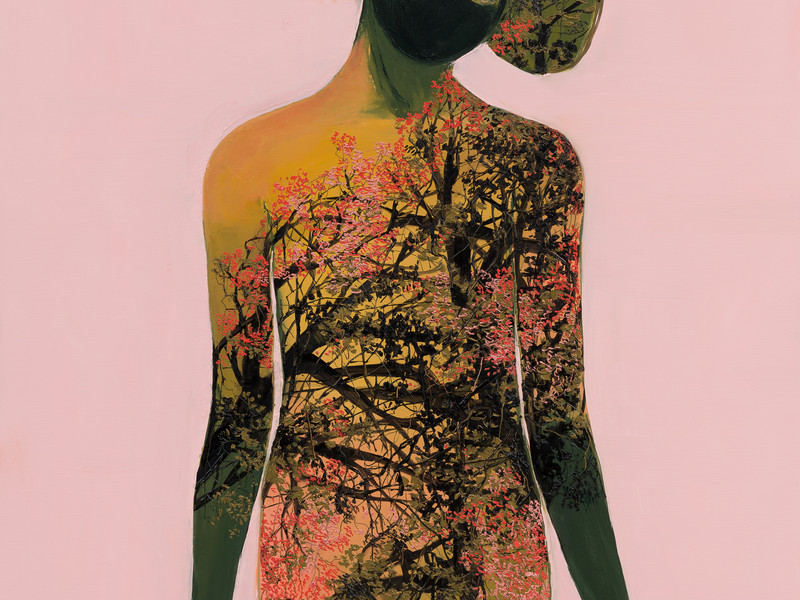

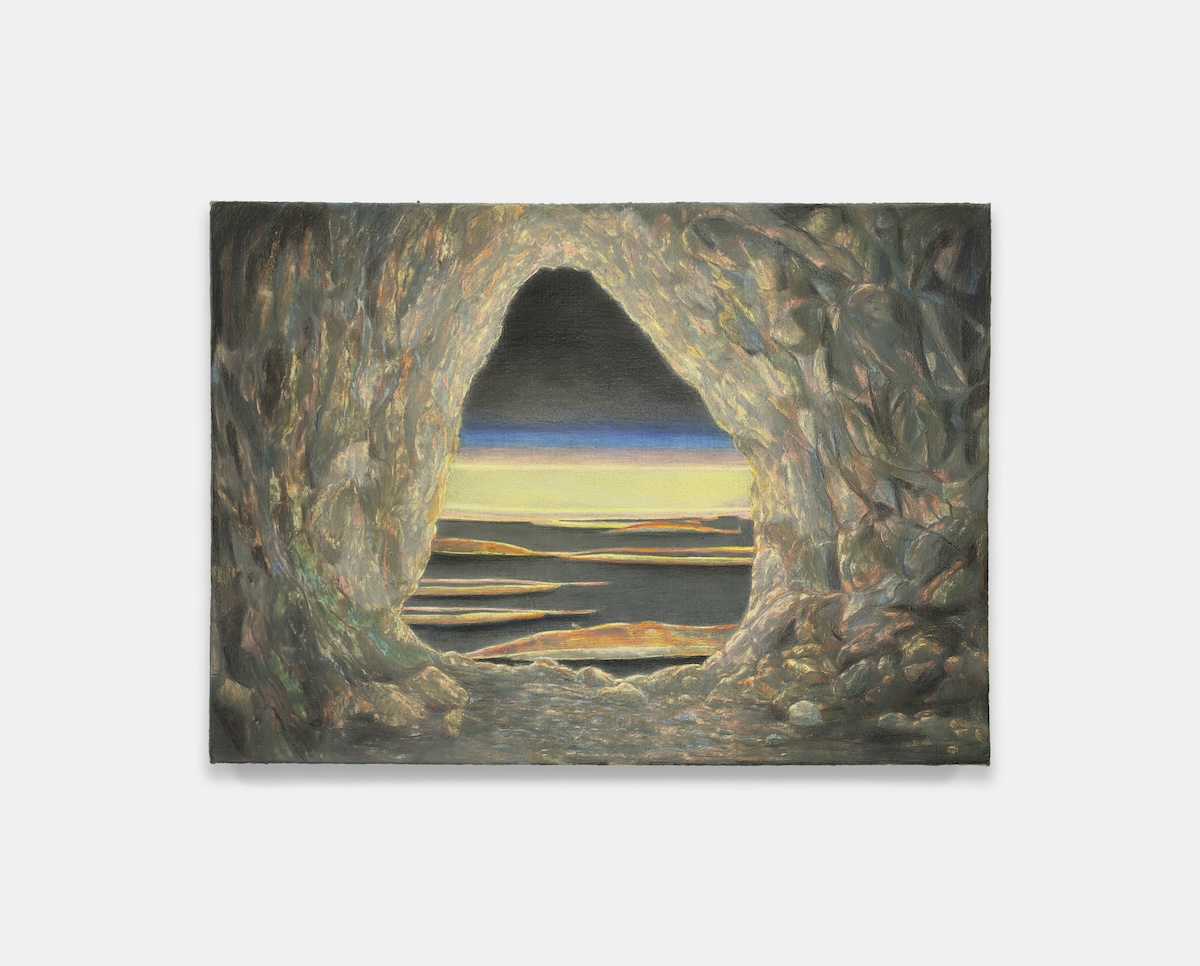

Sailor Moon Rising aka: Pacific Passenger, 2023.

Even the show’s environmental elements carry palimpsest connotations. Cranes soar throughout that same self-portrait — in China, they symbolize longevity and luck, but these birds feature prominently, too, in the murals across Alamosa, CO, where the birds pause for a month or so each fall during their annual migration. Maybe the Navy man seated beside the sunflowers in Sailor Moon Rising aka: Pacific Passenger (2023) just likes those flowers, or perhaps he’s optimistic, as they’d allude. Or, maybe he’s from Kansas, where they adorn state highway signs.

Yi Hou’s affinity for the Beat poets first attracted him to America. He has yet to travel the country himself, though. Maybe he’s better off. We’ve met many people out here who espouse their open-mindedness without demonstrating it. One man in Iowa told me about his gay friends, but called protestors “thugs.” Americans appear inept at estimating themselves, but art actually does expand horizons. Another man in Idaho said that while discussing “On The Road” with a friend, he was shocked to learn there’s gay sex involved. “I’ll be damned,” he said upon a return read.

Exposure is the answer to the biases still dogging America. Maybe representation isn’t the final solution, but it’s a good start — one that yi Hou is evidently mastering. “I can actually refuse any kind of closed meaning or thesis in whatever I make,” he said. “That's what I was doing with this body of work — the work inherently has a kind of politics and thinking behind it, but I feel it was less didactic and a lot more free.” Seeing alone has its power. The beat of life is an exercise in it.

The beat of life is on view at James Fuentes until November 16, 2024.