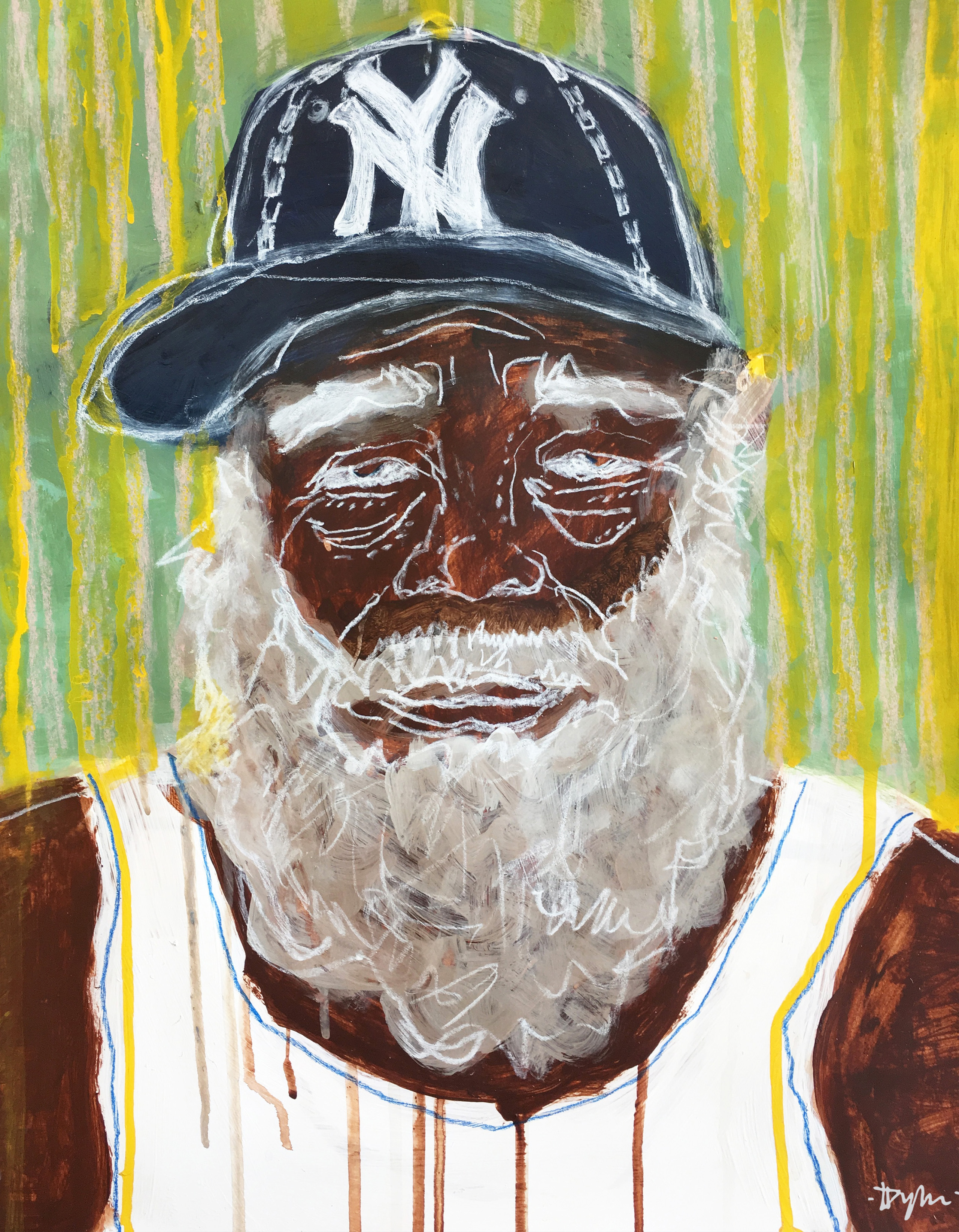

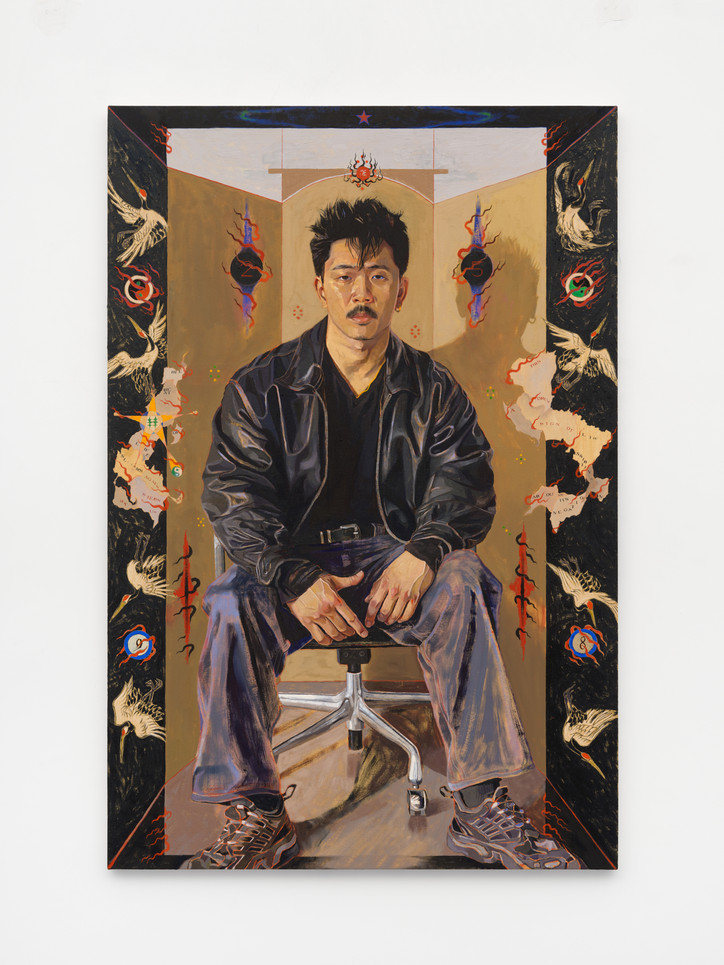

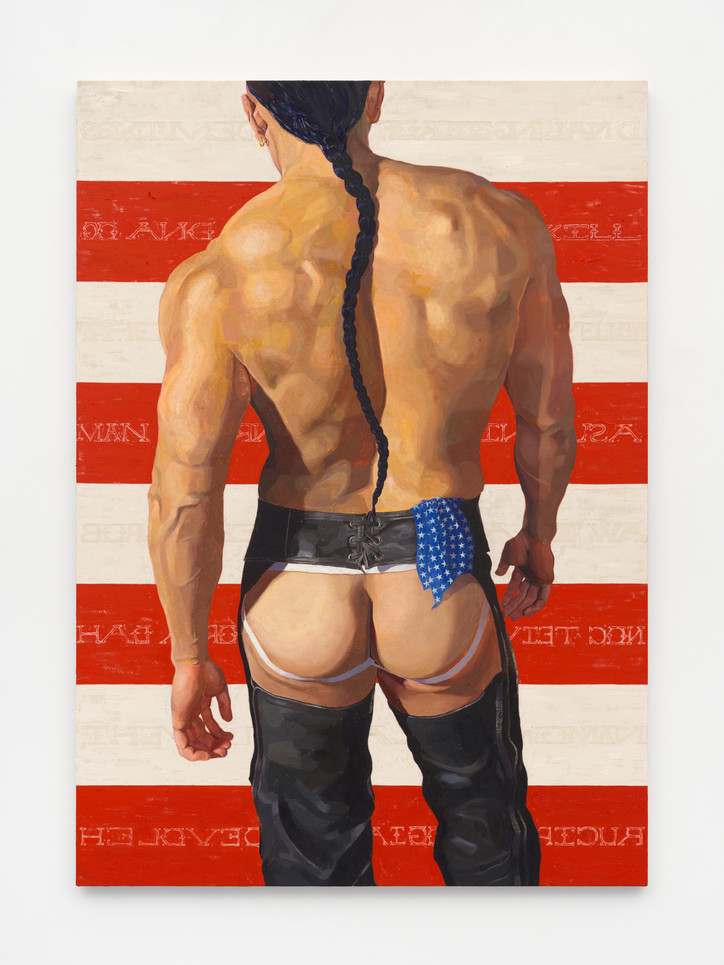

This initial artwork hails from yi Hou’s ongoing Coolieisms series, which reclaims a 19th-century slur for exploited Chinese rail laborers by depicting Asian figures in the trappings of Americana.

“Was there a leather daddy back in the 1800s working in the mines?” yi Hou mused. “Probably not.” In Coolieisms, though, he uses his own visage and imagined characters to forge fictions that highlight stereotypes about Asianness, masculinity, heteronormative culture, and more.

Yi Hou has previously spoken about the paradox of representation, that newfound art world fixation. Representation isn’t necessarily action, but it’s necessary for an equitable society. “It can be a burden to think about these things, but it's also quite generative,” yi Hou added. Symbols carry historical meanings, while also offering canvases for each viewer’s projections. They’re ephemeral, but spark material impacts. There’s a chilling reality, after all, to rooms full of people singing “Go and kill the yellow man,” regardless of which politician might be playing it.

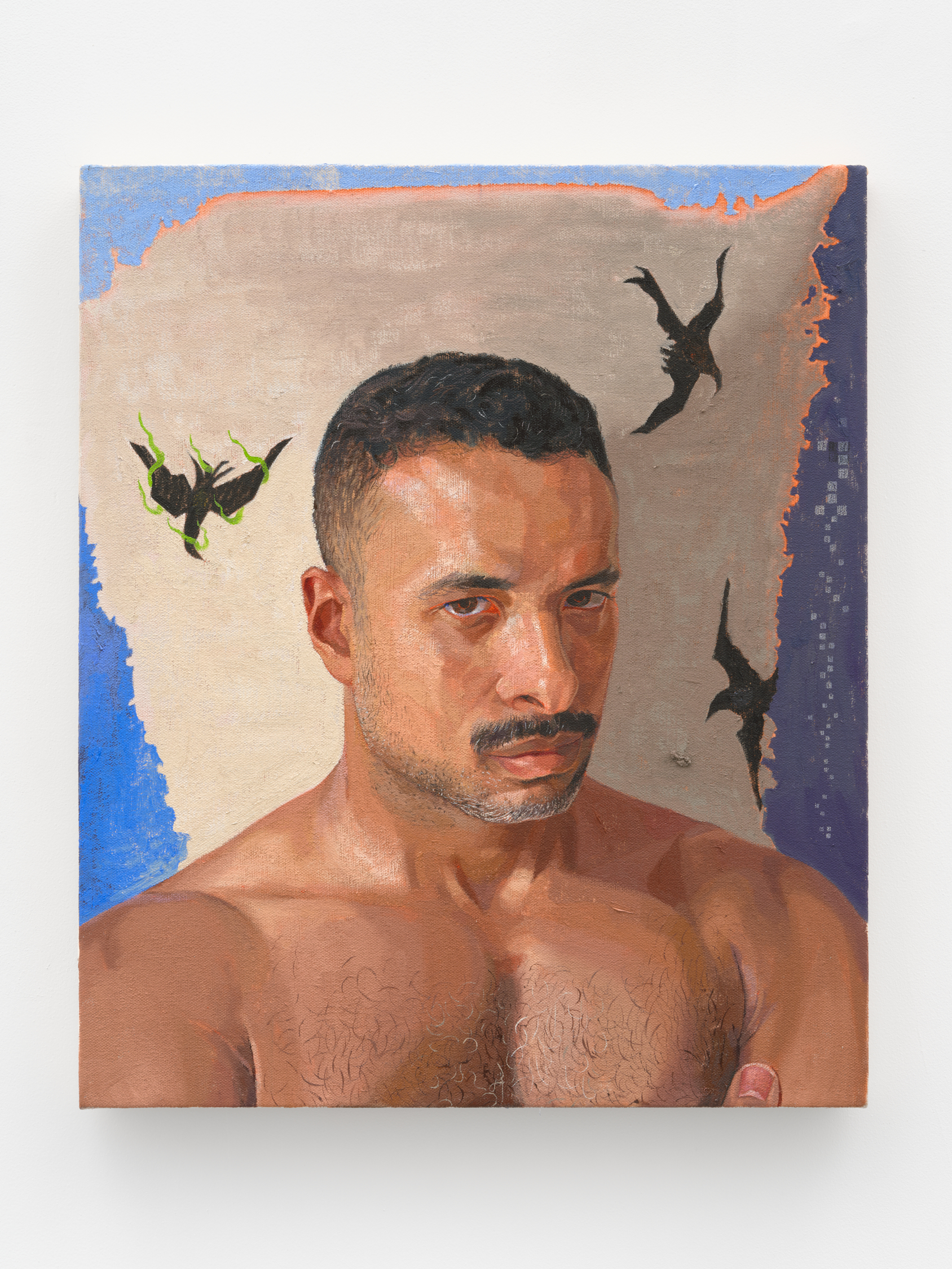

The Coolieisms series was once the one place yi Hou exercised license. “I was interested in the ethics of portraiture and trying to not commit any symbolic violence to another person through a painting,” he recalled. “As I got older, I was like, ‘wait, none of my sitters give a shit about that.’”

Symbols offered a sort of camouflage that enhanced while encrypting meaning. They’re active here, too. Yi Hou’s use of the color wheel proves somewhat new, but he’s harnessed sheriff’s stars and yin-yang signs before. “I've been interested in opacity and obscurity, generating mystery or opacity through these symbols,” he said of his compositions. “Because I've talked so much about them, they're a bit transparent now.” In another interview, yi Hou noted that sometimes indirect communications convey more. Thus, he’s set such icons ablaze in works like Self-portrait (25), aka: The beat of life (2024), “to further obfuscate the meaning behind them.”