Premiere: “Hold Me” by DeepFaith

Watch “Hold Me” below and keep track of DeepFaith wherever you stream music.

Stay informed on our latest news!

Watch “Hold Me” below and keep track of DeepFaith wherever you stream music.

From social media management and event promotion to web design and curation and so much more, it takes a village to make Level III happen. In addition to co-founders Dennis Franklin and Antony “Ant” Ramirez, the work of the collective is made possible by Will O’Brien and Faith Cheung, as well as Chim Tasie-Amadi and Lilah Beldner (not pictured above).

office joined Level III during one of their radio sets for this shoot, featuring DJs Suavez, Syd, Shekdash, and friends of the collective. Later on, we caught up with Dennis and Ant and discussed the origins of Level III and their hopes for the collective. Read our conversation below.

Brook Aster— How did the two of you meet? What were the early days of Level III like?

Dennis Franklin— We met sophomore year of college. I was in an apartment on 125th Street and Broadway, [living with my friends] Lani and Will. Ant would come over all the time because he knew Lani, and just hang out, but I didn't really interact with him too much because I had three jobs at the time. I don't know if we ever formally had a conversation the whole of sophomore year.

Towards the end of sophomore year and moving into the summer, we had this group chat of all these Black sophomores who were working in finance that summer. We all were working incredibly hard jobs during the week and we wanted to have parties on the weekends. And Ant had the craziest apartment.

Antony Ramirez— Looking back now, it seems unreal. I lived on West 107th Street. The apartment was huge; it had four rooms, we had a big living room and we also had an outside patio. We would clear the living room area, with the couches pushed to the walls, and you could still sit on the couch, but there would be a lot of dancing space. Then we would set up outside and we would invite everybody. That's when Dennis started DJing.

DF— It was incredibly convenient because in my freshman year, I had been rushing this frat on campus and it just didn't materialize. We had all these speakers in the frat house that then got dissolved. We were told to get all this stuff out of the house by June or something. I was like, well, these would be perfect speakers to bring to this kid's apartment, who I'd only met like three times. We went to Guitar Center and bought this $500 amp and went over to his house and put them up on stands in his living room, and I put the DJ booth in the corner. For the first party, we texted this group chat like, tell everybody you know to tell everybody you know.

Did you have any criteria for who could come? Especially given that these parties were at Ant's home.

DF— We had no restrictions on who came. We really didn't care, we just wanted to build the party. It was a full BYOB situation. We probably packed it with 250 people in this basement, but then outside, there was a terrace that had these stadium steps on it. You could have like four levels of people just chatting and when you walked out, it looked like a whole function.

AR— We even had a mini trampoline there. But there was no AC, so we had this massive fan in the corner that would just go left to right, and everybody's sweating, sweating, sweating.

DF— People would just come in waves because they would show up whenever they found out about it. So it started around 10, and I'd start djing and we'd probably end every time around 4a.m. or 5a.m. There'd be waves of the standard friends that we know and then there's this whole community of Nigerians who go from Nigeria to London to New York, and they'd all show up too. Sometimes people leave, and show up again at 2 a.m.

AR— We never had any problems with people that came to these parties. There were never any safety issues. Everybody felt welcome and we were never trying to play the cool guy or be like, you can't come into my party. We welcomed everybody, like please invite your friends! I feel like we had a good grasp of who we were inviting generally. Even the strangers we knew were decently good people. And it was amazing.

We were very consistent with throwing them. Sometimes it would be like 8 p.m. and we'd say, “yo, I think we should do a party again.”

DF— It would always be decided maybe an hour or two before it happened. Then people would come from the Lower East Side all the way up to 107th to go to this party at like 8 or 9 p.m.

AR— I would literally go and buy alcohol with my own money, and I was just happy that everybody was having a good time. We’d throw a party and immediately think about the next one. Then we started thinking about throwing more official events, and we did our first big event in Manhattan.

DF— It was an open bar, and we probably sold 350 tickets to that. And it was l the first club that I had ever played at too. It was an interesting experience because for so many of those people, they had only been to parties that summer in this basement that had no structure to it.

We were like, damn, people really will show out for this! The overall community just wanted to be with each other. You always see the familiar faces, the familiar friend groups and whatnot throughout each event.

I'd be remiss to not mention Jaden as well, who was one of Ant’s roommates at the time who unfortunately passed away the fall after that. He was battling heart cancer, and had heart surgeries every single year pretty much since he was born. He was one of the really core people of that group who would get a lot of people to come to the parties.

About 14 of us went to his funeral in Cincinnati after he passed away in September, and that was a big moment for our larger group recognizing how much of a friendship we had all built. That summer had really changed so many people's lives, and gave a lot of us a sense of connection to the city.

DF— We went abroad to London in senior fall, and that was a pretty impactful experience for me. We were going to all these parties that were just so incredibly well run, but also just musically very vast; people exploring genres that we either had never heard of or had been scared to play for other people in the US. London is just so much of a more open space.

I remember I played at a venue called Dalston Den. The ceiling was probably 8 feet high. I was playing all jungle drum and bass, going in on what my knowledge was of that. People came up to the decks and just started banging on the decks — in a good way, taking their shirts off and just going crazy. There was just a different energy there that we really wanted to be able to embrace in like in New York.

We came back full force that spring. We did our first event called Saturday Sessions, and then another one called Open The Garage. That one was really great — it was first one where we were moving away from an audience of mostly college kids. It was just people who found us and thought the event was cool. From there it was like a pretty easy way to start moving ourselves into more exploratory genres, exploratory DJs.

How did Level III Radio come about? How do you view the importance of curation and platforming other DJs?

AR— We had this great space, and we thought, all right, what can we do with this space that adds to the platform that we already have? Dennis and I, for the most part, have a lot of similar musical interests. But we started asking, what are things that I like? What are the things that he likes? And how can we put those together?

We were coming home from our day jobs and just putting DJs on our TV and sitting there and listening and being like, what do you think about this one? Why do you like this DJ? Why is this DJ better than this other DJ? Why should we have this DJ versus that DJ? We began to see the radio as a platform to put together our musical interests when it comes to the DJ scene in New York specifically, and integrate them in a way where the Level III audience gets to see where Ant, Dennis, and anybody else think the sound in the city is going.

And this episode isn't out yet, but there's this Dominican DJ that we brought on called Fried Platano, and he has a really big following within his community. I’m Dominican, and he played some stuff that I personally hadn't heard before. So I reached out, and he came on and did the radio show, and rocked it. It was amazing. I showed him the song he put me on to, and told him, “I owe you for showing me this because you just brought me into a whole different music scene that I hadn't known about. Thank you for that.”

It's something that I hope that people think when they hear Level III Radio. I hope we’re able to contribute to others what he contributed to us.

DF— Halfmoon BK was the platform that I got started on. Originally the show was just me doing mixes and the like. It would play on Saturday afternoons. I wanted a platform for me to be able to showcase my range of sounds across the board, in a more mellow, low-tempo type of space.

But then I thought about all these DJs in the community that I love to go watch and see perform, or who have done shows for us before. I think that being able to showcase their sound in a controlled environment with our audience was something that a lot of people haven't experienced yet, because we had posted sets from the live events that we had done but in live events DJs will come and they'll obviously try to contour their sound in the middle ground between what they like and what the audience may like. So to me, it wasn't as authentic as they could possibly be. I wanted to be able to give them that platform to be able to just do whatever they wanted to do, and every DJ so far has done that. Almost every set that we've had is completely different genre-wise.

The coolest part for me is that both of us are genuine fans of these DJs. They're not necessarily massive touring DJs, but every single person on there, when they start playing, I'm literally gonna stop everything I'm doing to listen because I think they're one of the best DJs that I personally know. There's so many people who are seriously dedicated to their craft.

And we're very young too compared to the majority of the DJs that have been on the show. We're both 23, and the majority of people who are on there are at least 26 or 27, if not older, so we feel very humbled in those settings. These are pros at their game. I'm learning more from them than they are from us, absolutely.

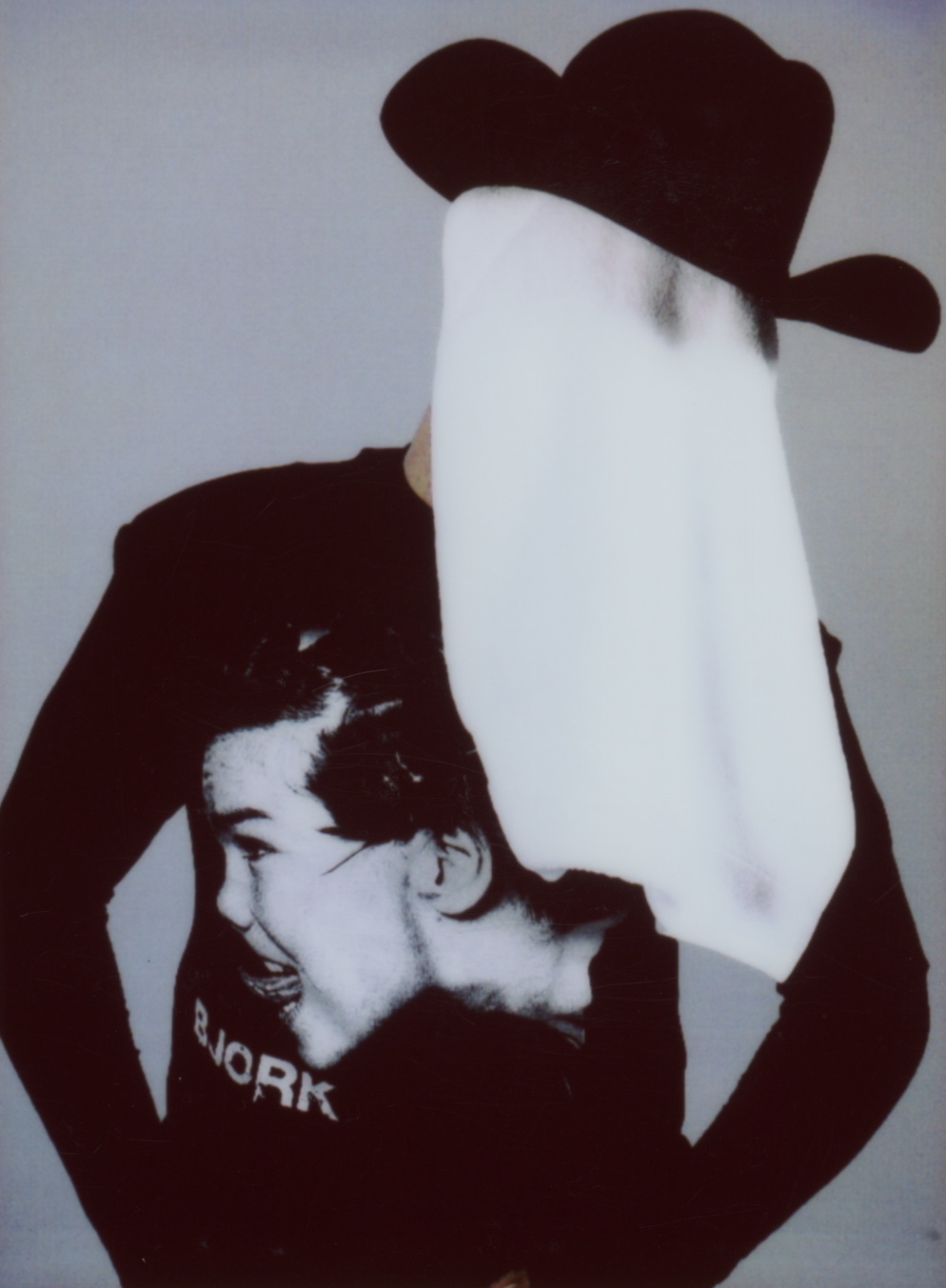

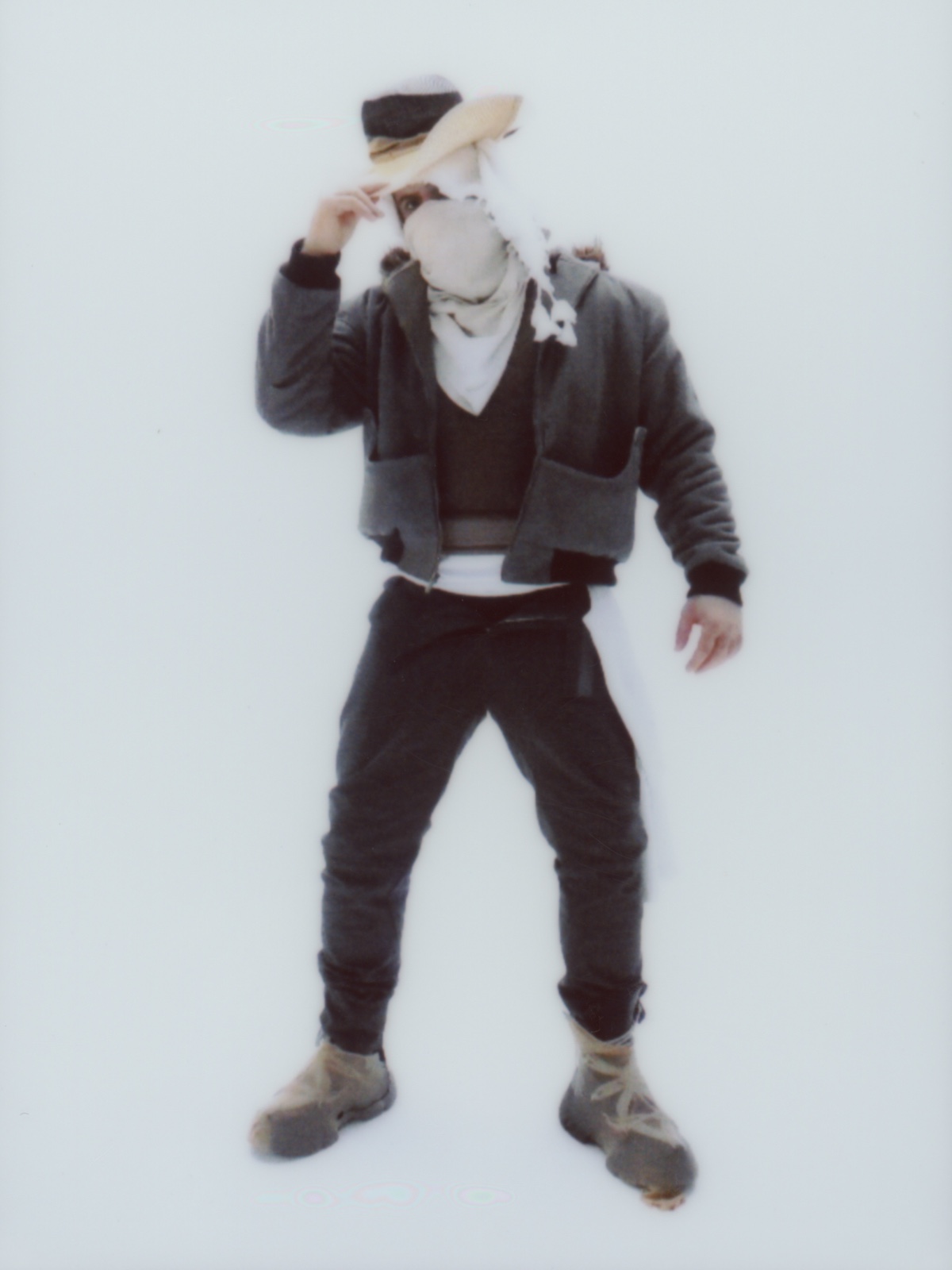

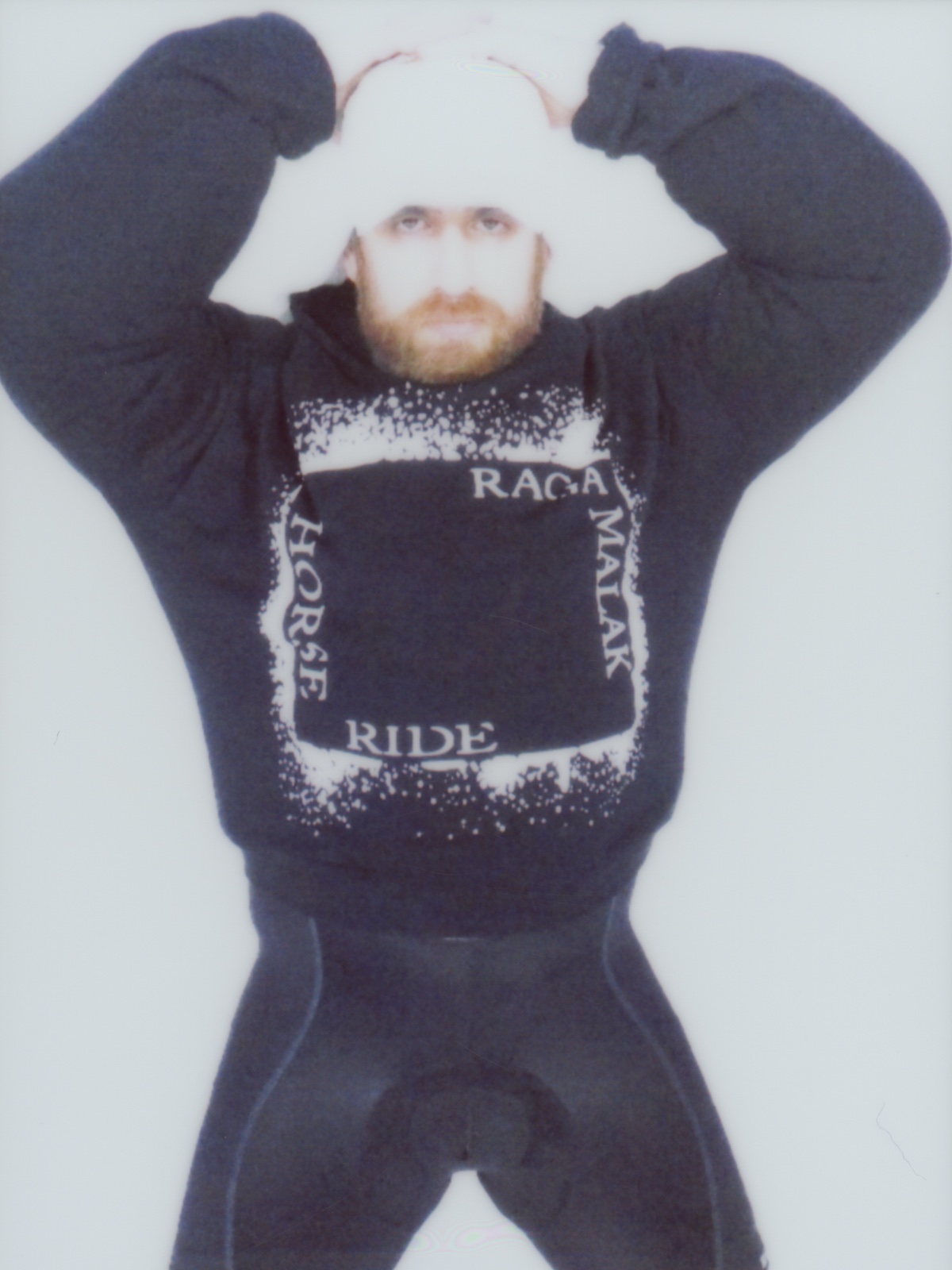

ANDREW wears COWBOY HAT by STETSON, JACKET by CRISIS EVOLVED, TOP by ENTIRE STUDIOS, PANTS by RAGA MALIK, BOOTS by RICK OWENS

[Originally published in office magazine Issue 21, Spring-Summer 2024. Order your copy here.]

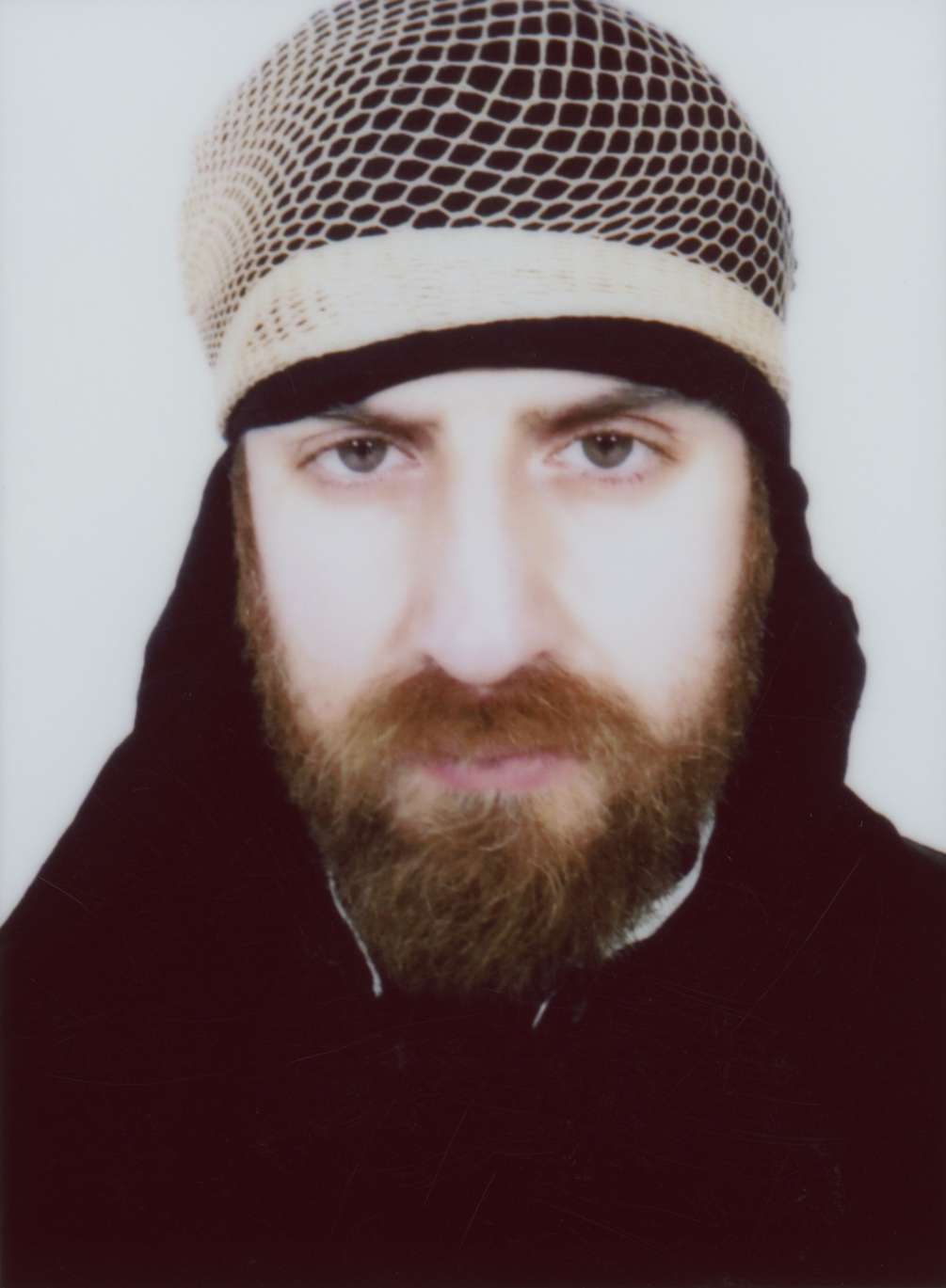

Born and raised in Zahle, Lebanon, Makadsi immigrated to the United States with his family when he was 19 years old and has lived in New York for well over a decade. Though he’s fiercely loyal to the city, he says he has been enjoying the slower pace of Los Angeles, using the extra time to work on producing his own music.

“I’m going to play some original tracks tonight that I produced that I’m really excited about,” he says, a slight smile peeking through his beard. But Makadsi has no plans to release anything at the moment: “If you want to hear it, you’ll have to come to my set.” When we arrive at Paragon, there is already a line of people spilling down the sidewalk. A cursory scan of the crowd reveals the typical Myrtle-Broadway ilk of the 2020s: racially diverse and visibly queer 20-somethings, more than a few steadily puffing away with cigarette in hand, all of them suited up in their Saturday night finest and ready to dance.

Makadsi has an hour to kill before his set, so we head to the “greenroom,” a repurposed room in the back of the venue that, evidently, was once a commercial kitchen. I lean against a deep fryer as Makadsi tells me about his early life in Lebanon. He and his family left the country due to the escalating violence of military conflict, but the memories of his adolescence that Makadsi shares are far from macabre.

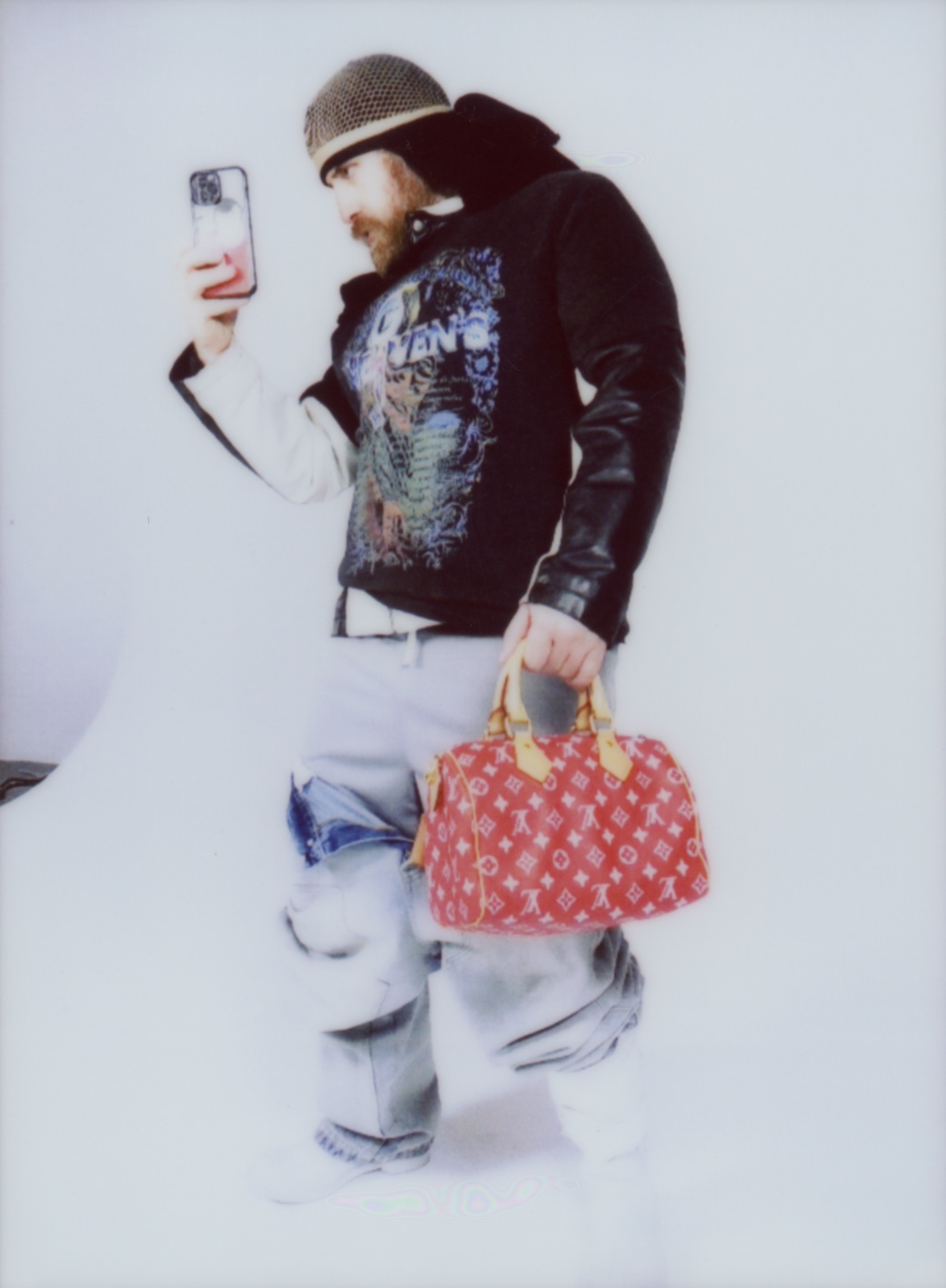

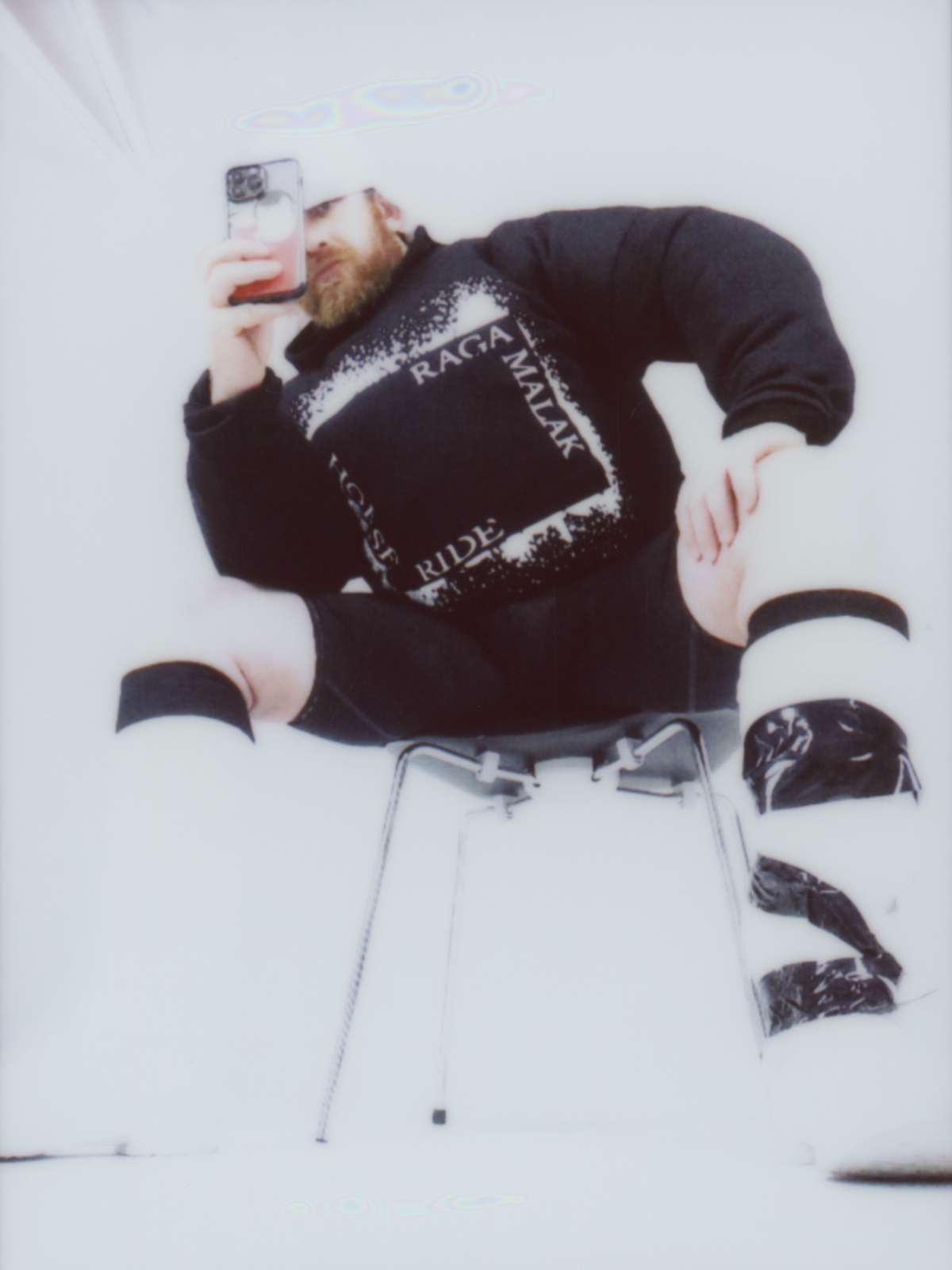

ANDREW wears TOP by BARRAGAN, SHORTS by PRO CLUB, PANTS by PAURA, BOOTS, BAG by LOUIS VUITTON, JACKET and BOOTS are STYLIST’S OWN

“Growing up in Lebanon, we were such party animals,” he reminisces. “We love life. We’ve been through a lot, socially, politically, economically, and we've been through wars. We have that stamina and mentality, that nothing is gonna come between me and my good time. It showed me how raving and activism can go hand in hand.”

He expresses his belief in the power and importance of revelry as a salve for anguish, a salve that is needed in this present moment more than ever. “I think our healing is going to take years,” he says somberly, citing the COVID-19 pandemic, the rising cost of living, recent political upheavals, and our overexposure to news and information among the factors contributing to cultural malaise and a collective feeling of despair. “It’s like we’re in a blender trying to figure out what the fuck is going on. People really need a space where they feel safe and away from the chaos of the world.”

But for Makadsi, the dance floor is not apolitical, and safety is not necessarily synonymous with complete escapism. Early in his set, he plays a mix of “Dammi Falastini” (دمي فلسطيني), a song by Mohammad Assaf that has become a protest anthem of the Palestinian resistance. The lyrics triumphantly repeat “my blood is Palestinian, Palestinian, Palestinian” in Arabic, asserting Assaf’s love for his people and his willingness to sacrifice for his homeland. In May of 2023, the song was temporarily removed from streaming services in what many pro-Palestinian activists condemned as yet another instance of censorship against Palestinian voices.

Makadsi has been vocal on social media about his support for a free Palestine for years. A quick scroll through his current Twitter feed shows a long stream of reposted news and content documenting and condemning the latest rounds of atrocities committed in Gaza since October of 2023 — a “textbook case of genocide,” as described by former top United Nations official Craig Mokhiber and numerous other human rights experts and authorities.

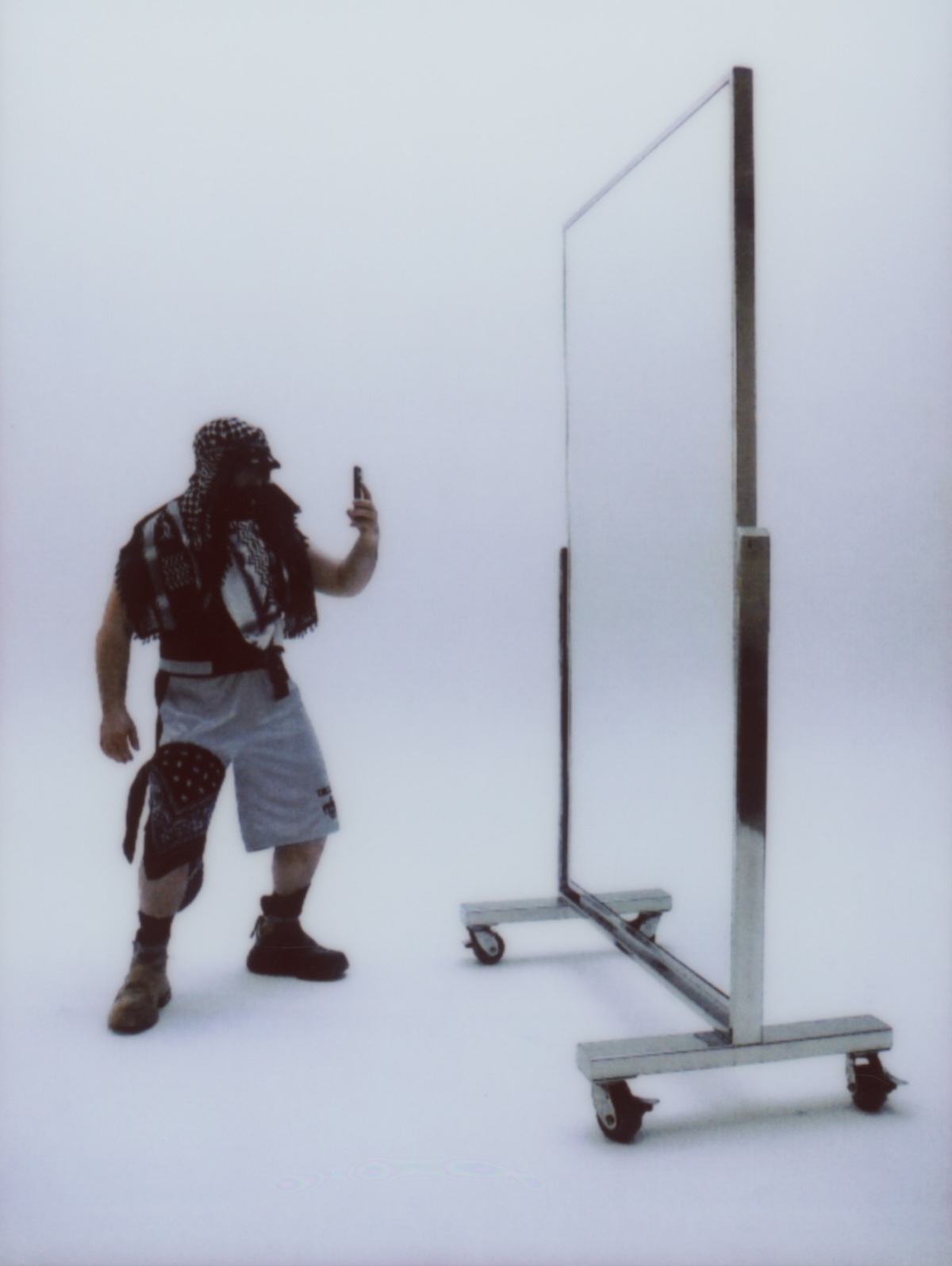

ANDREW wears TANK by RAGA MALIK, SHORTS by RAGA MALIK, BOOTS by RICK OWENS, KEFFIYEH and BANDANA are STYLIST’S OWN

The keffiyeh, a black and white patterned head scarf like the ones shown photographed on Makadsi for this story, is widely known as an emblem of Palestinian resistance and is often worn in the West as an expression of solidarity with the Palestinian people. But before it became a Palestinian political symbol in the 1930s, the keffiyeh was worn by nomadic communities known as the Bedouins, who migrated pastorally and herded camels, goats, and cattle throughout the Levant region and the Arabian peninsula. Inspired by his memories of seeing his father and other Lebanese men wear keffiyehs and cowboy hats to go hunting, Makadsi collaborated with stylist Eddie Lopez Bautista to reconstruct the image of the Bedouin cowboy. The keffiyeh is still familiar and commonplace in Lebanon, and the history of the symbolic garment is intertwined with Makadsi’s heritage.

Including “Dammi Falastini” in his set is Makadsi’s way of channeling the collective energy of the room into a unified will. “Music is such a unique language,” he explains. “Even if you hear a song and you don't understand the lyrics, you can still feel the essence and the spirit of it. I cannot help but react to the world in my art. It’s human instinct. I believe art in general can make an impact on people, but music is so easy because people consume it pretty much daily. You can paint the world you want to see and live in. To be able to deliver these messages and still have people dance — it’s ceremonial. As a group, our vibration is heightened, and we can make even more noise and deliver that energy to a further space.”

For Makadsi, the energy of the people on the dance floor exists in a symbiotic relationship as he plays a set. “I'm very privileged to be interactive with the New York dance floor,” he says. “Its energy is very specific and receiving. I love this scene, what it represents and stands for, and how people show up for each other.” That’s why, despite his breakneck schedule, Makadsi still finds time to go out dancing — “a lot, to be honest” — even on nights when he isn’t playing a set himself. Hearing the wide array of influences and sonic evolutions in the sets of his peers inspires him and keeps his ears sharp. “And it keeps me in touch with my community,” Makadsi says. “Unfortunately in New York and a lot of big American cities, it’s getting more and more expensive and difficult to live. But a lot of the youth still find a way to make it happen and bloom in the city. It’s very inspiring to see how resilient people are. And it's a privilege that sometimes I forget how hard it is, because luckily my parents lived 45 minutes away. I didn’t just drop like a parachute and land in New York.”

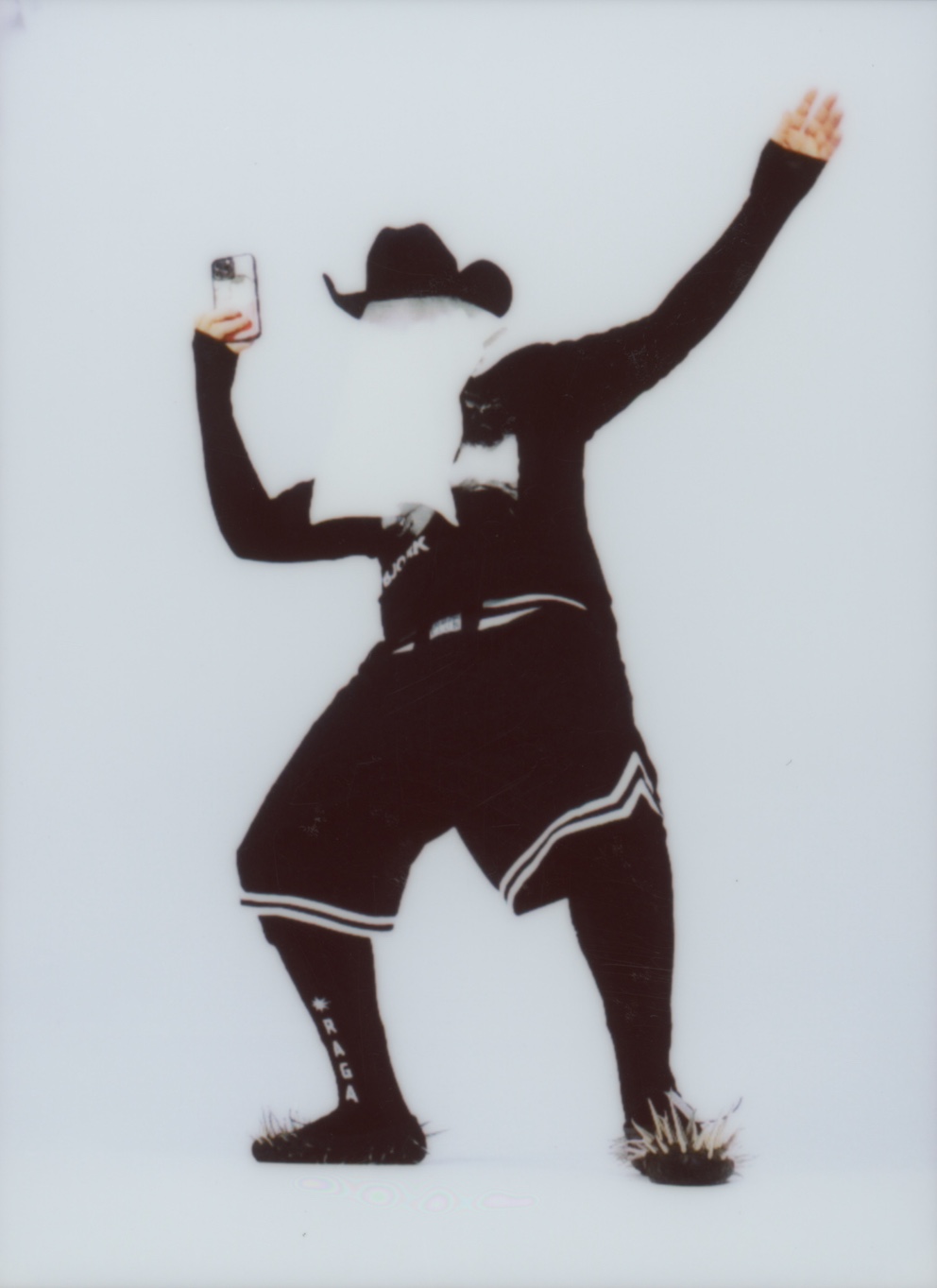

ANDREW wears TOP by FFF, SHORTS by PRO CLUB, SOCKS by RAGA MALIK, CUSTOM SHOES by ASLAN, COWBOY HAT is VINTAGE

After immigrating to the United States, Makadsi’s family settled in New Jersey while he enrolled at the University of Toledo in Ohio. In 2010, he graduated with a degree in Film and TV Broadcasting and moved back in with his parents in Jersey City, with the plan of eventually living in New York once he could find work. “Even when I lived in Jersey City, though,” he admits, “my Facebook still said New York.” Applying to job after job to no avail, Makadsi initially sought work in post-production but found nothing even after he widened his criteria. “The more time passed, the crazier I got,” he tells me. “I was applying to jobs that I knew nothing about, but I was like, ‘I'll figure it out.’ I just needed a call. I was driving limousines to the airport, doing so much unrelated career work.” He took buses into Manhattan for odd jobs and nights out, experiencing the city in small tastes and trying to hold onto hope.

Then one day, after over a year of job searching, Makadsi got a call with an offer for an internship as an assistant editor for a New York Fashion Week documentary. “It was the best way to start, to be honest. I was already in love with fashion, growing up and in college. That was my first stepping stone towards a career.” After that first internship, he was asked back to assist for a different documentary; his work caught the eye of the editor he was assisting, who enlisted Makadsi to help him edit some fashion films.

“With a lot of creative careers, the door is so hard to open,” Makadsi says. “But once it rains, it pours.” He found a full time job as a video editor at a production company, and soon he was working on fashion films of his own at a time when the medium was reaching its peak, building up a portfolio of work for brands such as Chanel and Louis Vuitton and artists including Kanye West and Jay Z. In 2014, Makadsi had the opportunity to work on visuals and video content for Beyoncé and Jay Z’s On The Run Tour. In another snowball effect, he was hired back for another project, and then another; by 2016, he was hired full time as an Art Director by Parkwood Entertainment, the production company and record label founded and chaired by Beyoncé. In 2020, he would take the helm as the Creative Director at Parkwood.

Unsurprisingly, Makadsi becomes reticent when it comes to his world-famous employer. As I anticipated, he says little about his day to day work, cannot divulge any information about her new album or satisfy any of my own random curiosities, and apologetically declines to answer thornier questions about her silence on Palestine. It’s no secret that “B” (as he refers to her) runs a tight ship, but his reluctance to speak about her is rooted more in collaborative courtesy than contract adherence. “That’s her work, that’s her art, and I feel like she should be the one to talk about it,” he says. “As an artist myself, it would be annoying for someone I worked with to go out there and talk about the work and the process.”

However, he does indulge me with one story. Makadsi tells me about the first and only time he visited America with his family as a teenager, a few years before they immigrated. He heard Beyoncé’s “Crazy In Love” playing for the first time in the hotel, and soon after he and his parents received a call from the receptionist with a noise complaint; Makadsi had been blasting the song on repeat. “After I flew back to Lebanon, I ran to the local discotheque like, I need this album. This is what America is listening to. You need to be on this. I was so proud to share my intel with them. There was something about the energy in that song, it took me to a different world. I grew up to her music and artistry and I never, ever thought I would end up working with her in this way.”

ANDREW wears COWBOY HAT, TOP by RAGA MALIK, JACKET by RAGA MALIK, PANTS by PRO CLUB, SNEAKERS by FLEUNER

For teenage Makadsi in the discotheque all those years ago, a creative career felt distant and inaccessible. “I grew up in the middle of nowhere, in a beautiful countryside, and I didn’t have access to information like people do now with social media,” he describes. “I didn't really have a mentor. Growing up, I always wanted to do it all, but I had no idea how to articulate my thoughts and ideas.” However, even without a clear path before him or role models from his community to look up to, Makadsi had a premonition about what his future held. “Based on the instinct in my heart, I would always tell my friends that I would be a director or a music producer,” he recalls. “I didn’t have anything to back it up. Now in the weirdest and most romantic and soulful and organic way, I arrived at that destination that I manifested when I was 14.”

When he started college, he didn’t aspire to or even fully understand what the titles of art director or creative director entailed, but the world-building principles he learned from studying film gave him the foundation for his future role.

“Learning about the mise en scène, and what that means to film — you're creating a world, and each of the design decisions you make all funnel towards a final image. That was the beginning for me, of understanding that all the creative decisions that you make on a project are essential to the big, big idea that you're trying to drive to the finish line.” Similarly, his film education came in handy when Makadsi began to experiment with making his own beats and mixes. “I didn’t necessarily understand that language at all in terms of writing music, and music theory,” he says. “Sound design was my introduction to making music and audio.”

Makadsi had always been a deeply appreciative connoisseur of music, but his journey as a DJ began one weekend in the summer of 2019 when he and a group of friends decided to rent a house in Provincetown, Massachusetts. Makadsi and George Najm, who would later become his manager, arrived a day or two before the rest of their friends, and on their first night out dancing the two decided to go home because they weren’t feeling the music. They hadn't known each other for long yet, but Najm knew that Makadsi had wanted to try his hand at DJing for a long time. “So he and I went to the house, like, let’s just play our own music,” Najm recounts. “He downloaded software on his laptop and started mixing at home — out of the gate, I was like, holy shit. I danced in the living room until four in the morning, just the two of us.” After the rest of their friends arrived, Makadsi played a set for them every night for the remainder of the vacation.

As the two grew closer, Najm began to buy DJ equipment and speakers, throwing parties on rooftops in Williamsburg and at houses on Fire Island so that Makadsi could continue to play. Word began to spread, and Makadsi booked his first gig — a private birthday party in New York — just a week before the COVID-19 lockdown swept the world in March of 2020. Stuck at home with nowhere to go, Makadsi kept playing. “I wanted a distraction from the world. It was my escape mechanism: let's turn the lights off and put some lasers on and DJ,” he describes. “It was definitely a transformative act for me.” The compulsory solitude allowed Makadsi, like so many others, to reexamine his life and work. “I felt that specific side of me that I was neglecting. I was working in film and [creative direction] but I hadn’t really focused on this part of me — the music. So I gave it all the love I have.”

ANDREW wears COWBOY HAT by STETSON, JACKET by CRISIS EVOLVED, TOP by ENTIRE STUDIOS, PANTS by RAGA MALIK, BOOTS by RICK OWENS

Najm sent a few of Makadsi’s mixes to his good friend, stylist and nightlife aficionado Paloma Perez, who moved to New York in 2004 at the personal request of Amanda Lepore and has hosted parties for years, including Unter, The Carry Nation, and Horse Meat Disco.

Perez was immediately impressed. “The talent was palpable,” she says. “I knew that coming out of [the pandemic], there would be new talent to emerge and he was it.” She was so taken by Makadsi’s mix that she broke one of her own personal rules: she asked Nita Aviance, prolific DJ/producer and ½ of The Carry Nation, to listen to the mix as a favor. “Nita is considered an oracle of music — particularly a voice on the sound of Brooklyn queer house music,” Perez explains. “She's not going to pretend to like something. People give me their stuff to pass along all the time, but I’d never done it before — that’s not my job. Nita says, ‘Ok, I’ll listen to it, because I know you wouldn't waste my time.’ And then she hit me back later and she said, ‘This is actually really good.’”

In the meantime, Najm was hatching a plot for a future when partygoers could congregate again. Nightlife at its best can be a carefree, safe space and a site of community building; but Najm knew that for nightlife professionals like promoters and DJs, it can also be intensely competitive and catty — or as Perez puts it: “it’s New-York-fucking-cutthroat-City.” Even in typical times, emerging talents are expected to pay their dues and wait their turn; those expectations would be heightened after the hiatus of lockdown, when even seasoned veterans would be hungry again to return to the booth.

So rather than trying to cozy up to promoters to try and squeeze Makadsi onto lineups at established popular parties, Najm started planning his own. “I didn't want to have to climb that ladder from the ground up,” he says. “[Makadsi] was good enough out of the gate. I could just start this. I just knew it.” Eventually, vaccines were distributed and venues started to open again in the summer of 2021. As soon as indoor events became legal again in New York, Makadsi and Najm threw their first party, presented under the name “FUNCTION.” Perez and her best friend Nirco volunteered to host; Najm discovered his own passion for event production, repurposing skills from his background in interior design and home building to design lighting and fog effects. “People who have lived here for over 15 years were gushing about it,” Najm recalls, “saying how it was one of the best parties they’ve ever been to in New York City.”

“It was just the epitome of fresh,” Perez says. “[Najm] knows how he wants things to look, Makadsi knows how he wants things to sound, but they always leave room for play. And music is the art of play. To honor this thing born out of love — it felt like a karmic investment.” Now that she has known him for a few years, Perez has a theory as to why Makadsi was so inexplicably gifted from the beginning. “He’ll never speak about himself this way because he’s too humble,” Perez tells me. “But as a Buddhist, I don’t believe in luck. I believe in fortune. Fortune is built. It’s earned through your actions. [Makadsi’s] talent is proof that he’s someone that has cultivated a lot of fortune, because of the way he treats people, the way he lives his everyday life.”

ANDREW wears HOODIE by RAGA MALIK, KEFFIYEH and SHORTS are STYLIST’S OWN

FUNCTION threw three more parties before the year was up, beginning to include additional DJs on the lineup with Makadsi. In the years since, their guests have included musician Chloe Bailey and ballroom legend Kevin JZ Prodigy — Kaytranada and Nita Aviance herself (now a friend of Makadsi’s) have also graced the lineup. Najm cut his teeth on talent management and promotion, booking Makadsi for sets at other parties in addition to FUNCTION and using their platform to give other emerging DJs a platform.

As FUNCTION solidified its place in the nightlife landscape, Makadsi was simultaneously hard at work at Parkwood as Beyoncé prepared to roll out her 7th solo studio album. Released in the summer of 2022 as “act i” of a three-act project, the critically acclaimed RENAISSANCE took inspiration from the history of Black queer ballroom, club culture, and house and disco music of the late 20th century. The record-breaking Renaissance World Tour followed in 2023, with 56 stadium shows across 39 cities in Europe and North America for a staggering total of 2.7 million fans. Featuring and sampling iconic figures like Grace Jones, Honey Dijon, Donna Summer, Kevin Aviance, and Kevin JZ Prodigy, the album was already characterized by an affectionate deference to its cultural forebears; the tour presented an opportunity to honor the new vanguard.

“DJs specifically have a big influence on this genre,” Makadsi says. “There’s credit to be given, to DJs that produce, even DJs that don’t — I’ve always been in love with the relationship between the artist, the DJ, the producer, and their contribution to the dance genre from the ‘80s to the ‘90s until now.” Though there were no opening acts officially advertised, Makadsi helped curate a selection of DJs to open for Beyoncé at nearly 40 of the 56 shows on the tour. The openers included the multihyphenate artists Arca and Shygirl, The Carry Nation, an array of FUNCTION alumni including KIA, Leonce, Dee Diggs, and Tory Stiletto, and New York City nightlife favorites such as Goth Jafar, River Moon, and office Issue 21’s very own Memphy. For Makadsi, highlighting the artists at the beating heart of contemporary queer dance music and culture was a no-brainer. “This was the perfect opportunity to share a platform with these talents, and I’m so proud of everyone that came and was part of the show,” he says. “It was just right — it was the obvious thing to do, in a way.” On the last stop of the tour, Makadsi stepped up to the decks himself.

Back at Paragon, I study Makadsi in the booth as he DJs. Watching his hands reminds me of sitting in the front row at a jazz club, close enough to witness as the tide of the room is turned with the improvisational flick of a finger. He never stops moving — always adjusting a knob here, turning up a dial there — and his decisions are entirely spontaneous. “I never stick to a script,” he told me, just before heading to the booth. When the music reaches a particularly ecstatic peak, I hear a wave of cries and shrieks from the audience. Makadsi breaks his unemotive laser focus for a moment with a pleased smile, punctuating each beat with a flourish of his wrist. I peer over the edge of the raised booth and can make out a pair of hands through the fog, reaching out and upwards towards Makadsi and gently trembling in a gesture of praise.

I step back and away from him and close my eyes, relinquishing my role as observer and letting the music overtake me. I think of the car, and Makadsi’s conception of his role as an energy worker; I think of the ancient peoples around the world who danced to heal, to call upon their gods, to bring about rainfall; and then I am not thinking at all, just moving, dancing. I have a long journey back to uptown Manhattan ahead of me, so I had truthfully only planned to stay for the first hour of Makadsi’s set, but before I know it, the lights are turning on to the decrescendo of his last track. It is 4:02am, and I can see the bartenders closing up. On the dance floor, seven dedicated dancers remain, each of them seemingly there on their own. They pay no mind to the sharp fluorescent glare above them, eyes tightly shut, still animated by the music, gyrating and twisting and spinning until the very last note. Outside, it has begun to rain.

The name Opium Angel sounds euphoric, yet mortal — a paradox that seems to capture your sound perfectly. How did you come up with it?

Omari Love— The first two letters of “Opium” are like “OP” for Omari and Pauli, but opium is also a drug that makes people feel really good. Euphoria is a good word, as you said, but it also destroys — that’s the mortal aspect I felt from it.

Pauli Cakes— And in a way it's like dying and coming back to life through ecstasy. Opium makes you feel euphoric, but if you do too much, you die. Then, you reincarnate into the world as an angel. The music isn’t dark, but it talks a lot about existence, deconstructing it, eating the body, bleeding, and then coming back — like the line going flat on a heart monitor. It definitely deals with mortality.

Pauli, as a New York native, how has your upbringing inspired your artistic approach? And Omari, coming from Minnesota, how has your background shaped your music, and what has been the impact of moving to New York?

PC— Growing up in New York, I’ve always been surrounded by different sounds. Music has always been my form of escapism in an overstimulating society. I have a very maximalist approach to sound because, in New York, there's always a million things happening at once. Growing up in the Bronx, I was constantly exposed to diverse music, like dancehall and futuristic Caribbean sounds. These sound bites have always been in my head.

OL— Growing up in Minnesota, there was always this battle between West Coast and East Coast music, but being in the Midwest, I was exposed to both. My dad loved West Coast music, so I grew up listening to a lot of that. For a long time, I didn’t listen to any East Coast rappers because I thought West Coast was the best. Knowing Prince was from Minnesota was also a huge influence — it was so unique, like nothing anyone had heard before, and I wanted that in my music. As I got older, I realized that every place has its own sound, and when I started creating music, I became a sponge to all of it. Moving to New York exposed me to things I didn’t even know existed, like noise music. Seeing artists like Deli Girls and Machine Girl was mind-boggling to me — it was so unconventional and inspiring.

Your EP has a strong political theme, especially on tracks like “Metallic” and “Need to Move.” There was a deep movement-based vibe to the lyrics. Could you expand on those messages a bit?

PC— For “Need to Move,” the line “abolish me, abolish you” comes from deconstructing the self — like, fuck my ego, fuck your ego. It’s about abolishing oneself and others, getting rid of the things that drag us down, like ego and authority. Nothing belongs to us, nothing in this world belongs to anyone — we inherit everything from those who came before us. The song is about abolishing it all and feeling the music, feeling the rage, without being trapped by ego or physical constraints. It’s like, “Fuck me, fuck you, we’re all pieces of shit, so let’s just dance and feel it.” Let’s just dance and move and feel it and not try to exist on some weird moral hierarchy.

OL— The EP was recorded during the time of George Floyd’s death and the protests that followed, which were focused on abolishing the police, the government, and the systems that oppress us. We wanted to engage in movements outside of ego. Whereas now, we’ve become kind of stagnant and almost regressed into this hyper individualistic society that depends on capitalism to move forward. Those songs speak all to that. I wanted to engage in movements outside of ego — to start understanding abolition and deconstruction, we have to abolish ourselves, our egos and unlearn the policing thoughts that live in our minds.

To me, art should be true to the artist while inevitably reflecting the time of the world they live in. I’d say you accomplish that here. What do you want people to learn from listening to your EP?

OL— The most important ideology I have is expression. People should absolutely express themselves and not let that be taken away, watered down, or diluted.

PC— When people listen to our music, I want them to understand that we’re attempting to break down binaries. We don’t care if a song doesn’t sound “professional” or “acceptable.” It’s about deconstructing sound and invoking inspiration and rage in people’s hearts.

OL— My view on expression is rooted in imperfection. That’s incredibly important to me — I’ve accepted that I’m not perfect, and no one I know is. The artists I revere most are fundamentally flawed, and that’s an important aspect of our music. It’s not perfectly mixed because I didn’t go to school for audio engineering — I don’t know music theory. Anyone can make music; you don’t have to be classically trained.

Who inspires you musically, and who did you channel while creating this project?

PC— For “Eat the Body,” the line “eat the body, drink the blood” has a Catholic undertone related to communion in Church and more generally, guilt, but I was also thinking a lot about my own religious and spiritual practices. What sacrifice means to different spirits in order to maintain relationships with them — in Santeria there’s a lot of blood sacrifice for spiritual rebirth, our loved ones, etc., constantly. Listening back to the lyrics, I felt they were very inspired by 5)/5 and my veneration for my ancestors and dead people that I work with and talk to.

OL— My aunts were the first to inspire me to make music — they had a duo called Double Shot, which was gangster rap. Seeing my aunt Tiffany’s home studio was so inspiring to me. Rappers have always been my biggest inspiration, especially in their poetry. There’s a quote from Tupac in an unreleased interview that came out in 2015: “We’re not really rapping; we’re just letting our dead homies tell stories through us.” At first, I didn’t understand it, but the more I made music, the more it made sense. It’s like there’s a collective, ancestral consciousness speaking through us, communicating very important messages.

I think music carries a lot of energy, which is what makes it so relatable — everybody’s felt the same in some way or another. What were some of the perks and challenges of working together?

PC— Everything we do together is a byproduct of our love and individuality, but also our unity. I think that’s really special. We both contribute our unique experiences and perspectives to create something mind-blowing and it never ceases to amaze me. Omari inspires me in every sense, and their production is incredible. Both of us being non-binary and having a deconstructed perspective on sound and music created this sonic bendiness that doesn’t really fit into any one experience, which is such a special advantage to what we do.

OL— Pauli has introduced me to sounds I wouldn’t have tried on my own, which is the cool part about Opium Angel and our collaboration. It’s like raising a child. In the beginning, it didn’t feel like a responsibility; it felt like something that came together naturally. That’s what music and expression are about — it shouldn’t feel like labor; it should feel like expression.

PC— Coming from different musical backgrounds — Omari with production and me with DJing and working with pre-made sounds — sometimes we butt heads because I can be impatient. The musical process takes a lot of patience, as I’ve learned from Omari, and it’s not like a DJ set; it doesn’t work like that.

Both your vocals carry a unique and enticing pitch, and the beat is dense and heavy, yet relatable. Having successfully merged a niche sound with public appeal, what are your end goals for this project, and where do you see yourselves after the release?

PC— I don’t want it to end; I want it to keep going. I want Opium Angel to be part of a larger musical archive that people can reference throughout time, history, and culture. I want the project to grow, and for us to create more bodies of work. Eventually, I’d love for us to have enough resources to record in a proper studio, because right now, everything is recorded on our computer.

OL— I want to continue developing a body of work and dive into more visual aspects, like recording videos and incorporating visuals into our performances. I’d love to perform all over the world, take our project everywhere, and collaborate with other artists.