quinn Doesn't Want the Cheat Codes

17 years old and making music since long before then, she’s dutifully peppered the internet with opaque tunes wrapped in inconspicuous packages, her scatterbrained sonic experiments separated solely by a smattering of odd monikers. In one SoundCloud loosie she quietly released as “DJ Weird Bitch” three months ago — its self-explanatory title: “dj weird bitch goes to NTS live headquarters and sets off a 7 yottabyte zip bomb on the wifi network” — she oscillates mercilessly between sped-up Japanese city pop sax solos, muddied rap-adjacent chatter, and glitched-out barrages punctuated by nifty transitions. Line that up with her most recent project, an eponymous 30-minute LP that puts mellow vocal performances in conversation with the controlled chaos of far-reaching musical contexts, and what you’re left with is a series of unconnectable dots. But when all is said and done, the dots may never have been meant for connection.

“I like adding shit to the cinematic quinneverse,” she says, poring over a bottle of Poland Spring in a busy internet cafe, as her longtime manager cheerfully nods along. It’s about a half-hour before noon on the Lower East Side, and in another thirty or so minutes, she’ll be headed over to the Good Company — a homely, youth-oriented fashion storefront on Allen Street — for a pop-up event where she’s slated to meet fans of hers in-person for the first time in her life. Come 7 PM, she’ll be in Brooklyn to play her first ever concert at the live music venue Elsewhere, chosen specifically for the intimate, living room-esque artist-to-audience dynamic offered by one of its smaller stages. She speaks with a hushed, gravelly-yet-playful inflection that sounds a little bit like a wise parent explaining why they aren’t angry with you, just disappointed. “I need to, bro,” she continues. “I like there being multiple characters to everything I do. I like people seeing me and being like, ‘Is it you? Or you? Or you? Or you?’ I like the vast discography thing. People hear the most popular song I made, and then they hear the ambient tape I made a year ago, and it’s like, ‘Yo, is this the same person? What the fuck?’”

Today, quinn is, at the very least, recognizable enough for me to spot her. When I arrive at the corner of Grand and Eldridge, she’s flanked by a cheery young group that includes her aforementioned manager Jesse, a lanky Finn Wolfhard doppelganger who makes esoteric music under the name saturn, the creative director of grassroots indie label DeadAir Records — to which she’s been signed since last year — and a few other giddy label-mates. “We’re trying to find this journalist,” she says calmly, scanning the surrounding streets behind ovular wire frames. When I reveal that I am, in fact, the journalist (she misheard my introduction over the chatter and thought I was another collaborator of hers named Sabbath), she tells me between poses for a group BeReal selfie that she’s only been in New York for a matter of hours.

The fast-paced day-to-day — from playing Fortnite and smoking weed with friends under a week ago, to trekking to the Big Apple for the most important 10-hour stretch of her career — is both on-brand, and an ebb she’s had to grow more and more accustomed to since storming into the limelight over the past 24 months. The track that put her onto most listeners’ radars was “i dont want that many friends in the first place,” a hyperactive rap number that sees her brazenly rail against the baggage of dead weight over the course of a whiplash-inducing upward climb like her own. At this point in her career, it registers as a necessary gospel. “If you can’t keep up, then okay,” she says matter-of-factly, midway through speaking on the collective progress-oriented mindset she shares with DeadAir. “We’re all trying to make a living. This is our life. And if it’s not your life, too, then no hard feelings, but we’re cutting you out.”

A military kid with a worldview informed by constant movement, and the unforgiving grind of a musical come-up backgrounded by nights spent on couches and floors, quinn both admits, and has been told by countless others, that she’s wise beyond her years. It’s a trait that will come in handy for the pivotal career junction she finds herself in, signaled in grand fashion by a day like today. At DeadAir, she’s gearing up to officially take on a tinge of increased responsibilities as soon as she’s legally old enough to sign them into action. She’s adamant about maintaining a majority of creative control over her cultural product — something she’ll be able to do more contractually when she turns 18 in December — and, with trust incurred among label peers who respect her for her wisdom, the keys are more or less being handed to her to do just that. “Moving around and being a kid and growing up," she says, "it’s never been too much for me, because it feels like I’ve always had too much on my plate.”

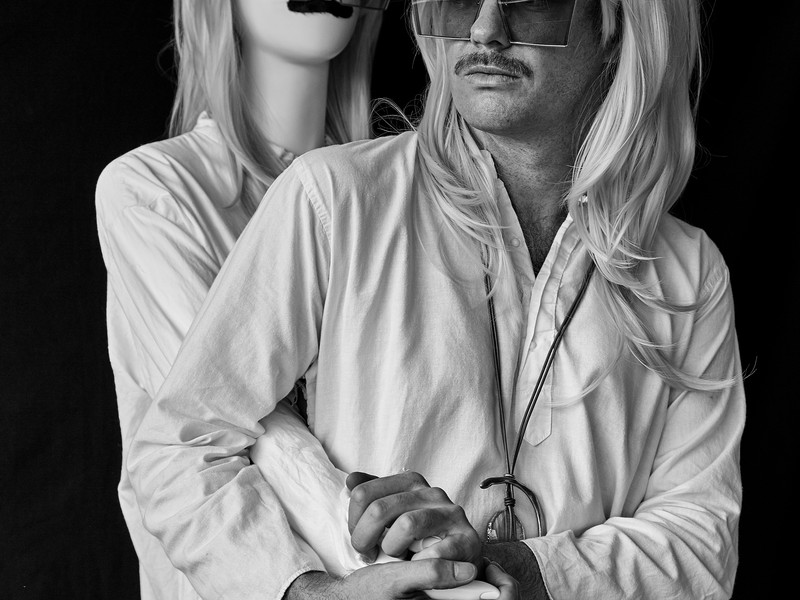

Quinn’s youth never really got to look like that of most other kids — no play-dates, no longtime friends, no sitcom-ready at-home hangouts — but at this stage, the best of both the young and old worlds melded together in her persona are spilling into one another. A matter of days ago, she was in Philadelphia playing the aforementioned Fortnite and smoking the aforementioned weed with friends and label-mates. These moments double as the That 70’s Show-esque blunt sessions she missed out on growing up, and the business meetings there won’t be any shortage of in the foreseeable future. “Shit gets hectic sometimes, but that’s just how we work,” she explains. Her Sopranos-esque spiel is somewhat enlivened by her all-black attire, reigning in an ominous inconspicuity familiar to her music: she’s wearing black leather boots, a pair of black tactical cargo pants, a spiked chain that swings menacingly from one black belt loop to another, and a black headwrap. “We work fast, and we work quietly. When it’s business, it’s all business. None of that drama, none of that family shit. Business comes first, then we worry about everything else. That’s why we rehearse first, then smoke weed and play Fortnite after. You know what I mean?”

This doesn’t mean that family shit isn’t in the equation at some level. Jesse Taconelli, a former music journalist who doubles as quinn’s manager and the founder of DeadAir Records, crossed paths with her through coverage of the local hyperpop scene for a publication he was working with. Much of the groundwork for DeadAir was laid by similar roots, lasting connections stemming from times Taconelli interviewed artists and “wouldn’t want the conversation to stop there.” His discovery of quinn came at the peak of a fertile-yet-futile industry moment in which young, upstart acts would take fairly new genres like hyperpop by storm, then whether due to lack of resolve on their parts, or mishandling on the management level, fizzle out as quickly as they emerged. He split with his job to found his grassroots label in hopes of giving quinn a shot at something better, and, in turn, stumbled upon something better for himself as well.

“I was working as a janitor at a Whole Foods when quinn hired me,” Taconelli says, a second after which quinn instructs me to “put this in the interview.” “When she came back from the hiatus and the cat mother [another of quinn’s several monikers, this one dedicated mostly to jungle] stuff, I just wanted to have a talk, and it changed my life. From being a full-time janitor at a Whole Foods to working with quinn.

“Our first convo was just about shoegaze music,” he continues, as the woman who will go on to save this interview by hunting us down and returning my forgotten tape recorder takes a seat nearby. “My Bloody Valentine was the topic. I could just tell we got along. I asked to hear [quinn’s] record — it was a very early take on Drive-By Lullabies — and the rest was history.”

“I sent him the draft,” quinn adds, “and he agreed to get to work on it, as a team. And yeah, shit was history after that.”

Drive-By Lullabies was quinn’s 2021 DeadAir debut, and its cover — her upper body holding an intricate drum machine in front of her head — quickly became an image seared into the brains of longtime listeners, and soon-to-be fans alike. Much like quinn’s overarching lore writ large, it spread like wildfire, mostly fueled by word-of-mouth. (I was sent an Apple Music link to it by a college friend after a long post-midnight conversation about the Neptunes sparked by getting lost on campus.) In its most streamed track on Spotify, the sinister, rustling PSA “from paris, with love,” she sneers threateningly abrasive mantras into a void studded with trap-infused vampire thriller beats and ominous, click-tracky snares. “You gon’ have to kill me if you want me,” she warns in the song’s first verse, her monotone registering as both numb and a little bit disinterested. The detachment makes her words all the more potent. “Put down your guns, approach me slowly / Black suit, camouflaged, can’t see shit / How you hop up on the wave, but you’re seasick?”

Much of the record banked on this on-edge ethos, a focal point of its messaging being hinged by the anxious sense of someone on the cusp of just as many dangers as triumphs. quinn, its month-old 2022 follow-up, sounds like something a bit closer to the light at the end of the tunnel — it boasts a more polished, less mixtape-ish feel; quinn’s vocals seem to come with ease; it feels like a message from the throne, rather than one from an aggressive contender for it — albeit, for all the ostensible ground gained, it refuses to let go of the rough roots that forged its peaks. Before I got a chance to listen to it in full, the same college friend who introduced me to Drive-By Lullabies sent me a link to “Two Door Tiffany,” the fourth track on the new record. “The way I see it,” she muses in its opening lyrics, “there’s a war inside me / and I don’t go nowhere, I don’t let myself go / So with those words out now, I think I’ll let you know.” Her parting message embodies the vulnerable chord her music has struck with listeners up to now: “This next segment is for anybody who's stressed… Depressed, uh, fuckin', I don't know, hahaha.”

For a while, this was quinn. “I was going through a lot,” she tells me, citing the comfort of her four walls as a reprieve she basked in before she was willing to do things like what she’s gearing up to do today. “I didn’t want to go through that outside of my room. I didn’t want to come here and still be going through some shit and ruin the whole experience. But now I feel like I’m recovering. I’ve been recovering from a very long depression. Now is the perfect time to see that there’s more to life.”

The sentiment wastes little time echoing itself. Upon entering the pleasantly air-conditioned Good Company — after getting lost several times en route, which quinn enjoys, because she’s planning to move out to New York soon and is taking every chance she can get to scope out the city — it doesn’t take long for us to see what exactly the “more to life” she’s talking about looks like. Before the first few awestruck fans enter, the room is occupied by the same cheery bunch from the corner of Grand and Eldridge, with the addition of DeadAir co-founder Billie Bugara, and a few giddy friends intermittently taking the first few group flicks of what will be a long day of “_______ mentioned you in their story” notifications for the phenom at the center of attention.

“She’s been on the label as long as we’ve had the label,” Bugara tells me, midway through a conversation about freelance writing and imposter syndrome. “Actually, the first piece I ever wrote for Complex was about her. It was the ‘Best New Artist’ thing, but it was, like, a blurb. We’ve always been at each other’s sides in a certain way. Because I’m not doing the music stuff like she is, and she’s not doing my stuff, you know? But we can still help each other out. We’ve been on a steady rise.

“When we started the label, it was just like, ‘How could we not have her on it?’,” she continues. “Especially with the trust dynamic and stuff, and how she’s responded to other, major labels. This fit is so perfect for her, and now we’re here.”

Back at Granddaddy’s Cafe, quinn told me that it was her uncle who informed her of “how evil the industry was.” (Before signing to DeadAir, quinn rejected offers from labels including Universal, Interscope, and 300.) “He educated me on that shit, because he’s seen it all happen. He was a DJ back in the 90s, him and my dad, Baltimore club, all that shit. They’re legends, they have no fucking clue. But he taught me the difference between business and a family.”

In the tiny interior of the Good Company, if it isn’t family, it’s hard to tell what else quinn’s DeadAir crew could be. The label’s modest clientele sheet is made up of quinn, the aforementioned esoteric act saturn, and the upstart indie songster Jane Remover. Aside from them, other figures that arrive at the Good Company to share laughs and selfies include the digicore innovator angelus, the concrete-grinned fashion heartthrob Oliver Leone, the Indiana-bred hyperpop scene graduate Midwxst, and the prolific eldia DJ Dazegxd. When followers of quinn’s begin to trickle through the cracked storefront door, and, over the course of the afternoon, the talkative congregation spills out into the surrounding streets, it’s difficult to tell who — from the local high school students nervously encircling their favorite artists to ask for photos, to the fashionable adults befriending each other over conversations about underground music — is on a pedestal, and who isn’t. Much like the modus operandi of her first show in a few hours, the scales are even, and it’s a familial sense that feels nurtured, if not intentional.

“I think it’s definitely a big change,” one local high school student tells me of the new album, “between something she would put out in, say, 2020, versus what she just dropped. You could tell it’s a big shift, whether it be in direction, or stylistic choices. I’d say it’s definitely welcome, because you could see artists that never really change from what they blew up doing, or never really grow. But with quinn, I feel like that versatility and the ability to go from some stupid electronics to some more chill, R&B type shit, makes her a really interesting artist to listen to.”

Another high school student, who goes to a school with mean science teachers in the Bronx, stopped by because he saw the pop-up on quinn’s Instagram story, and is actively deciding whether he will try to persuade his strict dad to let him attend the concert tonight. “quinn got me into Eric[doa], Eric got me into Midwxst, then Midwxst got me into the new wave of hyperpop,” he tells me. “It all started with quinn. quinn opened me up to everything.”

A more literal embodiment of the family-esque dynamic comes when quinn’s brother, an imposing-albeit-chill fellow quinn introduces as “the biggest dude you’ve ever seen,” arrives to the tune of frenzied commotion, hugs, and a large assemblage at the storefront’s window. He took a bus here from Baltimore the second he heard that the event was happening, and plans to get something to eat before biking all the way to Brooklyn for the concert once the pop-up ends (partly because he doesn’t want to risk getting lost on the Subway).

“I watched quinn grow up, man,” he says, toting a joint and leaning against a wall outside. “This been quinn’s dream. So when I heard the show was happening, no matter what I had to do to come up here, I was going to do it.”

quinn’s latest album opens with the mantra “there’s no need to knock the hustle when you kinda are the hustle,” and, one track later, features the triumphant assertion that “I’m in a new place, I’m in a new light / I’m where I’ve always wanted to be.” None of these factors — the hustle, nor the new light — can exist without the other, and for her, it’s a sentiment she’s embodied long enough to speak on from the outside looking in, rather than the dark-shrouded position she long occupied, wondering whether she’d ever get to where she is now. As much success as it’s already wielded, for both herself and DeadAir, the upward climb continues to prove necessary. But at least for now, no level of acclaim can convince quinn to have it any other way. “There’s fun to be found in the grind,” she says. “You stop grinding, that’s when shit’s boring. It’s like having all the cheat codes to the video game. The fuck you gonna do now?

“I mean that,” she continues, segueing to the opening mantra of her new LP. “There’s no need to knock the hustle if you kinda are the hustle. I am the hustle.”

Knocking the hustle often stems from not understanding it, and understanding quinn’s hustle looks like understanding her music. Fear not: if you never happened to understand it in the first place, then that’s great! Because she never wanted you to.