Real Slick, Jack: Psyche Organic Arrives in New York

Shop Psyche Organic at Happier Grocery and Dimes. Coming soon to @citarellagourmetmarket @unionmarket @gourmetgarage @deciccos @fairwaymarket plus many more.

Stay informed on our latest news!

Shop Psyche Organic at Happier Grocery and Dimes. Coming soon to @citarellagourmetmarket @unionmarket @gourmetgarage @deciccos @fairwaymarket plus many more.

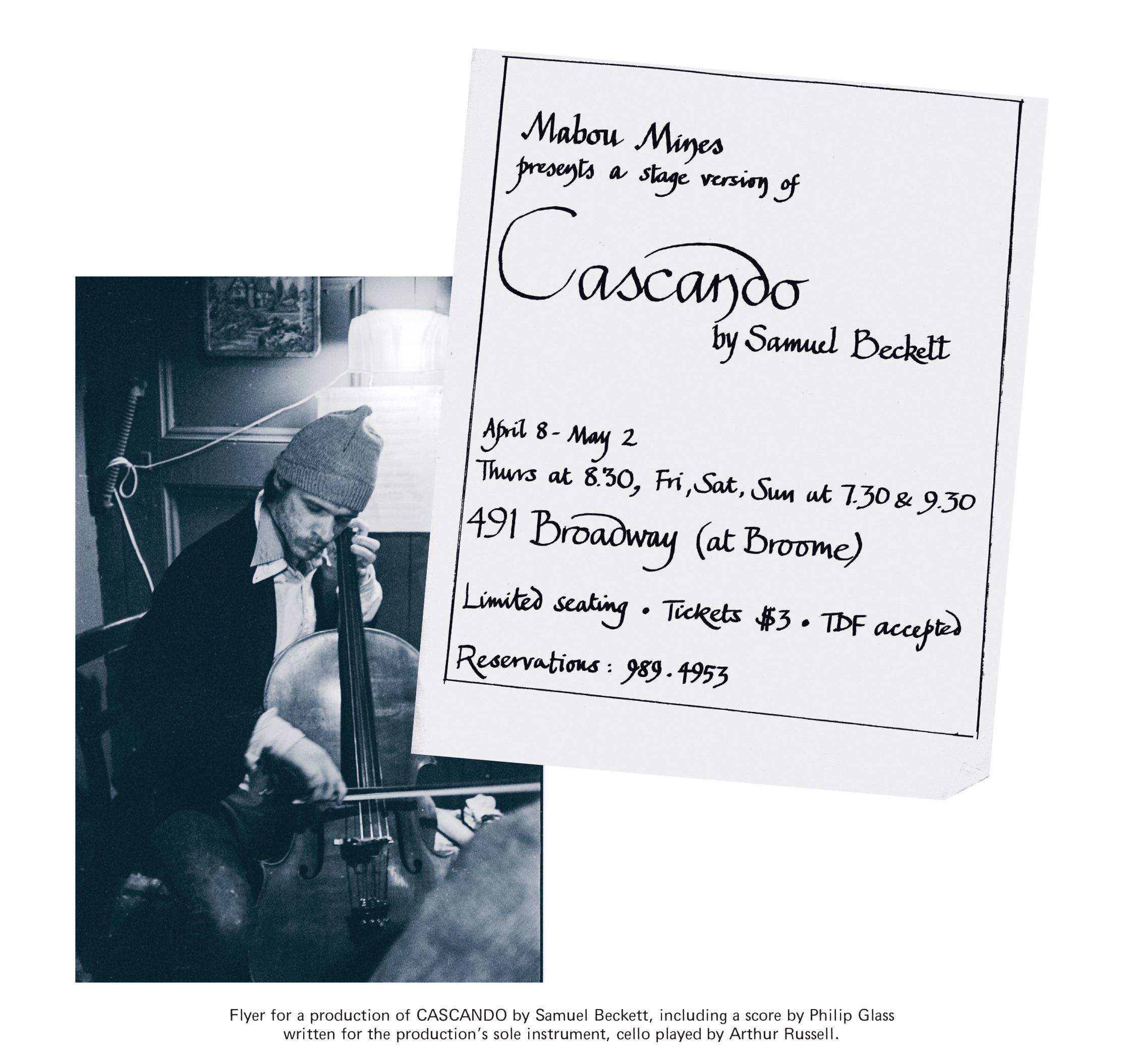

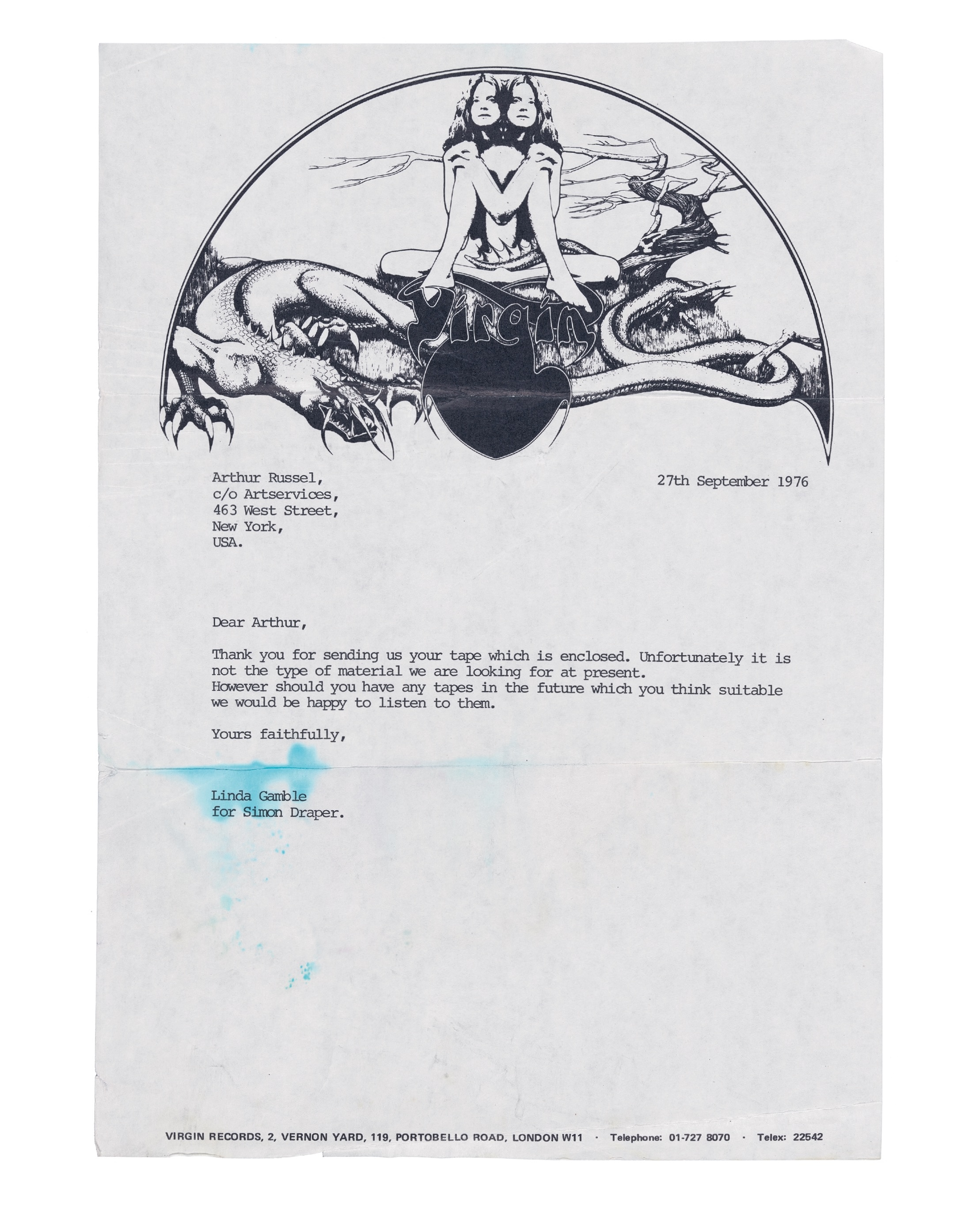

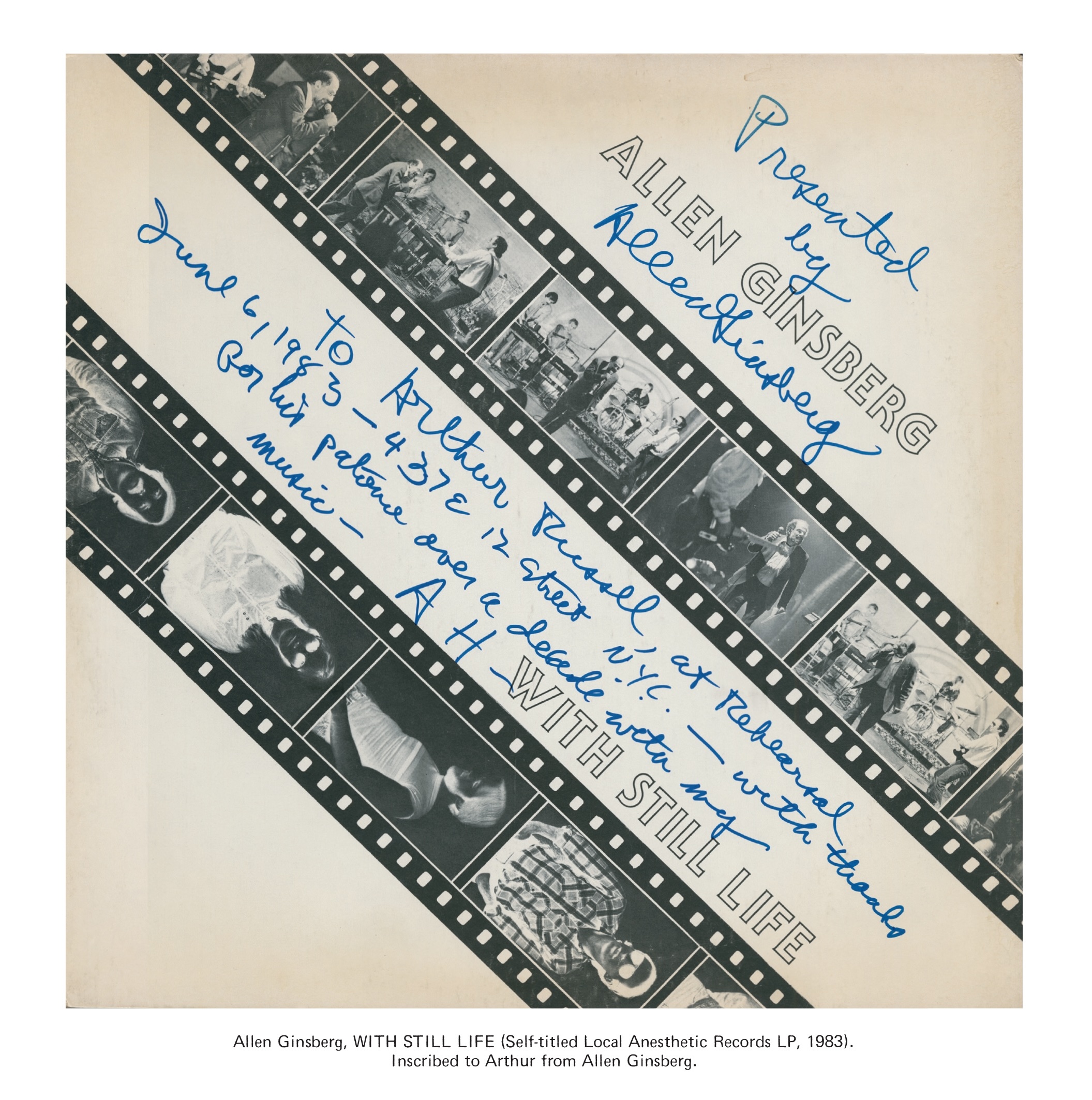

His work has been universally appreciated, sampled by the likes of Kanye West and Blood Orange and featured in the works of Philip Glass and Allen Ginsberg. In a way, his creative practice summoned multiple versions of himself through space and time. With most of his work being released posthumously, Arthur Russell’s identity somehow belongs to each individual listener. His work is often discussed more as a projection than as his own perspective.

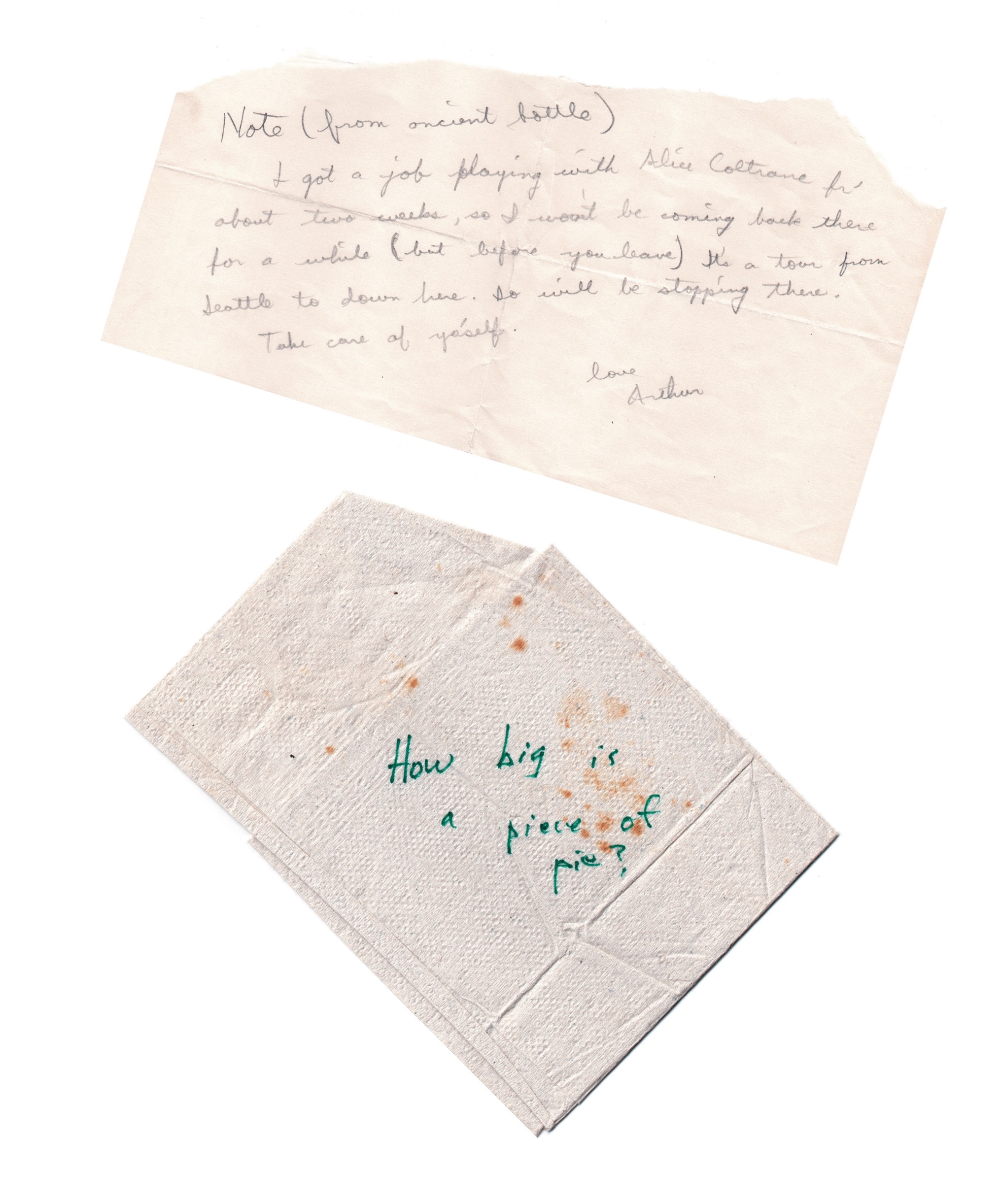

Richard King’s new book Travels Over Feeling: Arthur Russell, a Life, guides us through the legacy that Arthur Russell left behind. Pieced together with clues of brilliance, the book explores the genius of his ephemerality and the spirit behind his creativity. In an attempt to bring Arthur Russell’s words to life, the book comprises multimedia pieces such as notes, posters, and even grocery lists archived in the New York Public Library.

Why Arthur Russell as the subject for your book?

I’ve absolutely loved his music, and I don’t think I know many people who quite like his music. Most people who have heard of him, love him. In the case of Arthur, people don’t dislike him, they just haven't known about him. His music has come out largely after his death. There’s an element that we can make him whoever we want him to be. He was relentless and unable to finish anything which only showed his genius. He can’t help but be mysterious, but I wanted to know if it was possible to present Arthur on his own terms rather than project onto him. I think it’s very hard when there’s so little existing material to not project a version of Arthur that we want. His music is so remarkable that it’s a human response to create Arthur into this Guardian Angel like character. One dangerous projection is that he was some kind of martyr because of how he died. I wanted to see if the archive could present Arthur in his own words. I wanted to try and bring him a little bit closer to the sidewalk than this sort of celestial figure.

Everyone you interviewed seemed to have their own perspective on him. I felt like I was reading a documentary script the way it was visually portrayed. I found it so fascinating that at one point his sister said she learned so much more about him after he died through his friends. Could you talk about the conversations you had with his sister?

There are photographs of both his sisters in the studio with Arthur when he’s dying and stricken with HIV AIDS. There are several family photographs of him on holiday with his family. He participated in family life. However, Kate suggests that he was very absent even when he was physically present. He didn’t talk about his sexuality to his parents until he was ill. He had also run away from home, so I assume there was a lot of difficulty for him in working out where he stood in terms of what a family was.

I think for Kate and for the rest of the family there are a couple of things going on. One is that their father was just so happy that towards the end of his life he saw Arthur have success in the way that Arthur hadn’t when he was alive. He saw the music getting the recognition that he knew his son had craved. I think the other thing that happened was through the revival of Arthur’s music, they got to meet several of his collaborators and close friends. They were able to share with them a similar experience of Arthur's diffidence and social ambiguity, if we call it that. That was sort of comforting as well. “It wasn't just us in the family that didn't always know how to get through to him. It was everyone.” I think that's what Kate's talking about when she says people bring him alive. They partly bring him alive as there's an element of discovery in this mutual experience. One of these defining qualities included not being brilliant at communicating.

It seems like he had a really big community of musicians that he was constantly working with in the East Village. What was it like connecting with musicians who were part of his scene and maybe other characters that you met along the way?

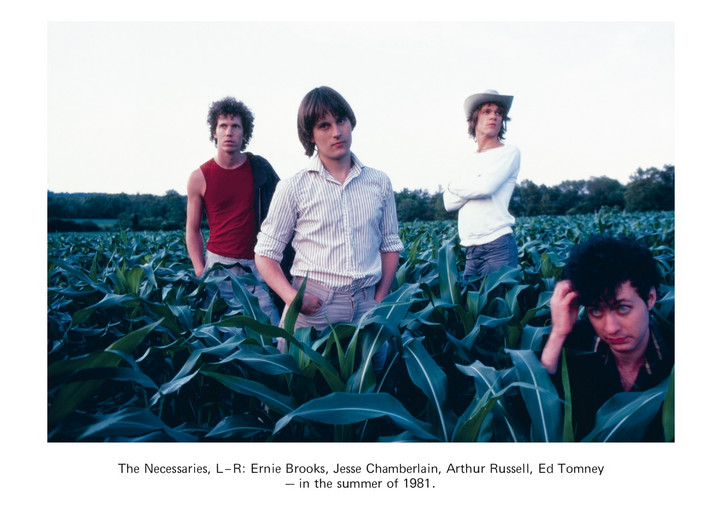

All of them were really remarkable people. I think some of them were maybe a little worn out of talking about Arthur. What was really rewarding for me and perhaps, to a degree for them was I was able to show them elements of the archive on screen. We could talk about the memories in front of us. I could talk about playing specific shows or chord charts. It allowed people to remember certain aspects of their relationship with Arthur, but it kind of made everything a little more specific as well. It brought me to sort of reorientate Arthur away from the myth through his daily life. For a lot of them, they could take care of their overheads by playing three shows a week or 10 shows a month in New York. Was that work kind of mutual aid, making 50 bucks of an evening, or was it a self supporting, shared creativity? I think it depends on what day of the week I was and what mood everyone was in.

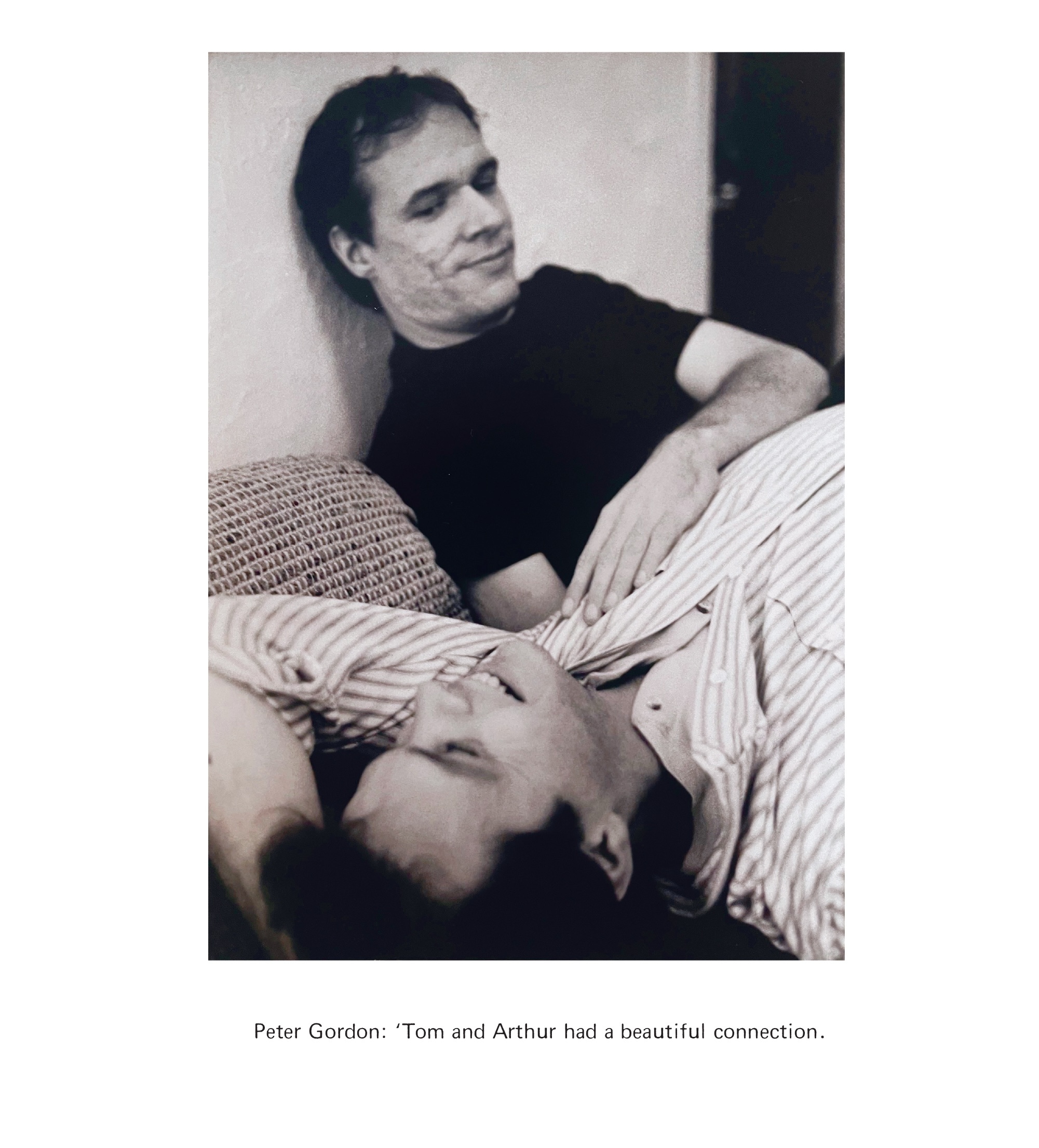

I remember reading in the book that Peter Gordon says they’d pass the same $50 to each other.

Exactly. It was easy to get work in Manhattan at the time in commercial music because they’re all obviously incredibly talented musicians. Arthur was different. He didn’t have a day job. Superficially, one might think that meant he was a bohemian, lazy guy who waited for the music to come, but nothing could be further from the truth. His colleagues said that he had a more pronounced work rate than any of them. He would be happy to live in penury, but he’d work on his music sometimes 18 hours a day. There was an element of them just playing together to get by I think as well. I showed Peter Gordon a setlist and he said, “Gosh, I saw that writing and chords too many times. We rarely followed what we wrote down. It was often quite chaotic.” Since they’re all really talented they knew what to play.

Referencing back to pieces from the archive seemed like an intense process. What was it like organizing the book?

I went to the archive four times, and each time it was about a week long trip, so I spent probably about a month in it. Each time I went I took a crazy amount of photos. I think by the time I'd worked out what had to go into telling the story I was trying to tell, it kind of developed its own internal logic. I spoke to most people three or four times. There were things that could be revealed about each element of his life that hadn't been revealed, so I didn't want to rush through his childhood or dwell on his death. When he released “Go Bang”, and “Is All Over My Face” he was also writing pop songs and writing an opera. Although that happened in 80 and 81, I didn't want 80 and 81 to not just be about The Loft, Paradise Garage and this mythical downtown New York, you know?

Yeah definitely. Speaking of his dance music, there seems to be a lot of synchronicity between Disco music and Indian music because of the drones and consciousness raising properties. Were there any other moments in the archive where his New Age experience came out or where he would use meditation in his notes?

When it comes to World of Echo, the phrasing and singing, but Arthur had singing lessons and his voice is extraordinary in World of Echo. He got to that place with his voice by breathing in his Buddhist practices. The idea of World of Echo itself is that we’re always changing and always the same. There’s a consciousness in World of Echo that feels almost divine. People seem to be drawn to this sense of secular prayer, and I think his music is a safe place for young people. In the book, he makes one last trip to the ocean to meet with his old Buddhist teacher, and his teacher refuses him. That level of rejection felt incredibly difficult for him. So in that sense, it feels like a presence in his identity. If I had wanted to I could’ve explored more about his practice, but I thought it would be anecdotal. People want him to be in the footage of Keith Haring's birthday at the Paradise Garage or at John Lennon’s apartment when he died, but I didn’t want to speculate how he could’ve been in the past.

What was it like seeing things from conception to end? From an idea to a fully developed piece?

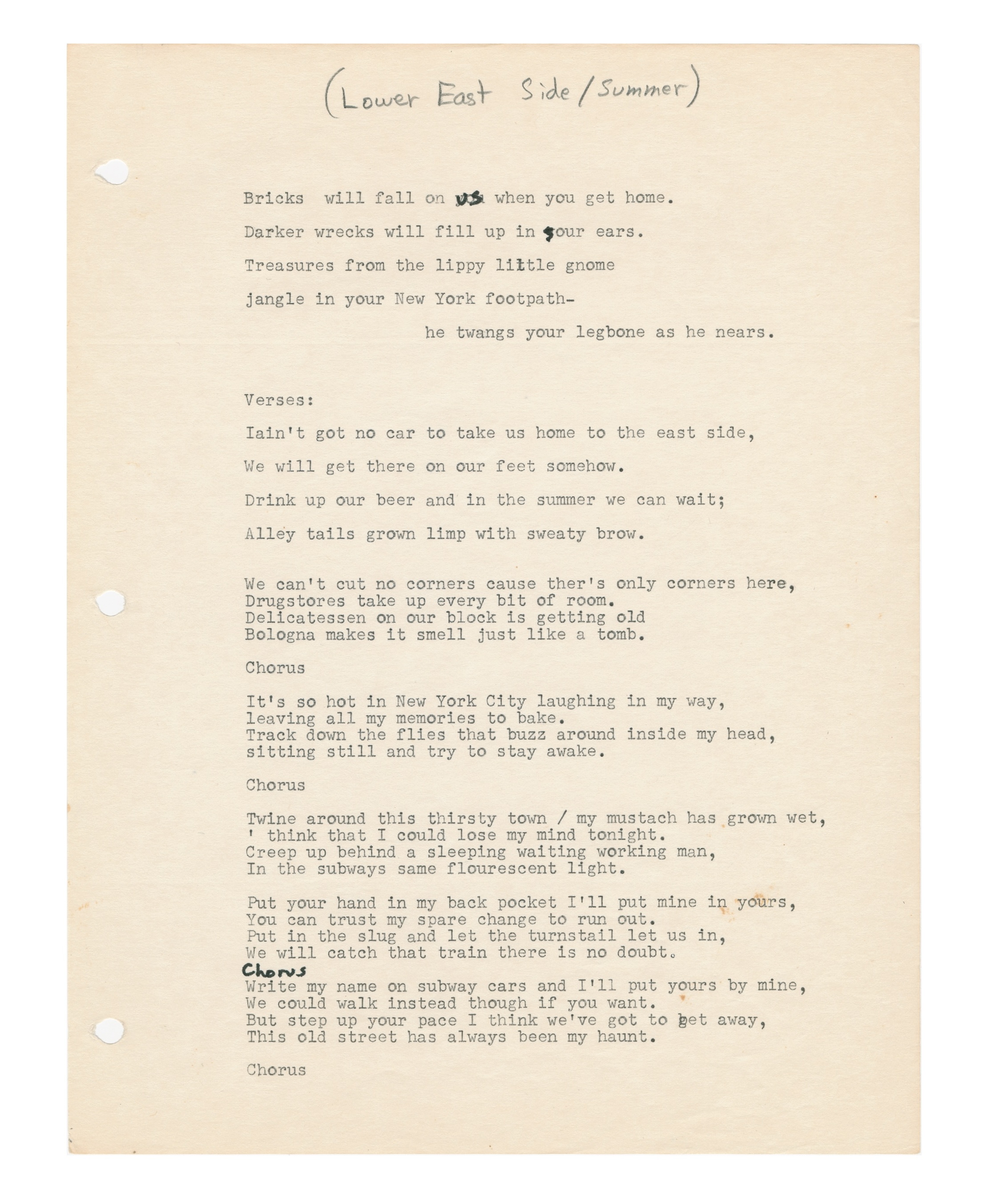

I never saw anything as a finished song. There were two moments where he’s frustrated and wrote snarky stuff like “my dick is big.” You can just tell he’s really bored. Two of my favorite songs are “Keeping Up” and “Wild Combination” and I included a work in progress of “Wild Combination” to show its development. I feel like the composition of the song was often more rigorous and challenging than the lyrics. There’s one about East Village in the Summer, and it’s so evocative. Nobody had seen it before, and as I was reading it, I could imagine him singing it. There were no cross-outs and no edits, so I think part of his talent was always to conceive of something.

Is there anything that you learned from his creative process? Any patterns you noticed?

He worked incredibly hard. He embodied that talent is enough. He always had a pen and paper in his pocket. I think the thing I learned most of all is how unbelievably open minded he was when it came to being creative. I got an enormous amount of peace from him. He was frustrated constantly, but there was incredible peace when it came to his own work. I imagined myself in his apartment, and even spoke to Lucy about what it would’ve been like to be living there during his time.

Speaking of Lucy, I was kind of jealous when she said her NYC apartment was only $150 a month.

It was dirty, cheap to live, and the city was full of exciting people. Magic happens when a group of people don’t have to worry about money and live in a big city.

We’re all heart eyes for Girl Dick. Blair Broll looked like Envy Adams if she were gayer, which is pretty hard to do. We start off with some party ethnography: “Where my bisexuals at?” An earth-shattering cheer. “Where my gay men at?” A loud and surprisingly low ‘woo.’ “So there are some tops in the crowd,” observes Broll. “Where?” asks a guest. I hope they found the top(s) they were looking for. “I want everyone licking nipples and getting sexy tonight,” orders Broll. By the first song, the keys player has their ass entirely out and is thrusting while playing. A fan has already made mouth contact with Broll’s boobs. Nice.

After their set someone asks for my number. It’s funny how different people hit on me — girls have their friends compliment me. Boys yell at me across the street and laugh about it with their friends. I guess queerness is about multiplicity. I end up leaving the queer art museum performance to go play beer pong (and win). Multiplicity.

The Voluptuous Horror of Karen Black rolls up in latex, pink suits, gingham, and their signature massive wigs. Painted red and green with black teeth, Kembra Pfahler flings pairs of underwear into an eager crowd with arms outstretched, seeking salvation in flying pantyhose. Voluptuous Horror’s fans sing along reflexively. At the end of their set, Pfahler sprinkles an unspecified white powder on us. Conveniently, inside the exhibition, the Bronx Móvil harm reduction table has Pride-themed “safer sniff kits,” complete with condoms, rainbow straws, a plastic cutting board, and fentanyl test strips.

Harm reduction is an inherently queer political action — not queer in the sense of sexuality, but queer in the sense that it functions outside of mainstream institutions. When cops and politicians refuse to take care of us, we take care of ourselves. In Gary Indiana’s Horse Crazy, a character speaks of AIDS and claims that the only safe sex “is if one person jerks off at one end of the room and someone else jerks off at the other, both trying to hit the same spot in the middle of the floor.” In a queer aesthetics class, we learned that there’s no such thing as safe sex, only safer sex. The same can be said about drugs. Public health rhetoric that criminalizes drug usage as a crisis that needs to be solved fatally overlooks the reality of drug use. The “stop using drugs” argument is eerily reminiscent of the “stop having sex” argument. There’s no contact without risk.

Something Blair said at the end of Girl Dick’s set stuck with me — while many of us can celebrate Pride by getting drunk and making out with strangers, we must remember that Pride is political. We must continue to organize, in joy and rage, for and around those in Palestine, many of whom may not have the capacity to celebrate Pride during genocide. The argument isn't that we must be constantly solemn, or that we must forego celebrations, but that we must also channel constructive energy to ensure Pride becomes a lived reality for everyone. It’s a catchy phrase — “Pride was a riot.” Perhaps it’s time we live it.

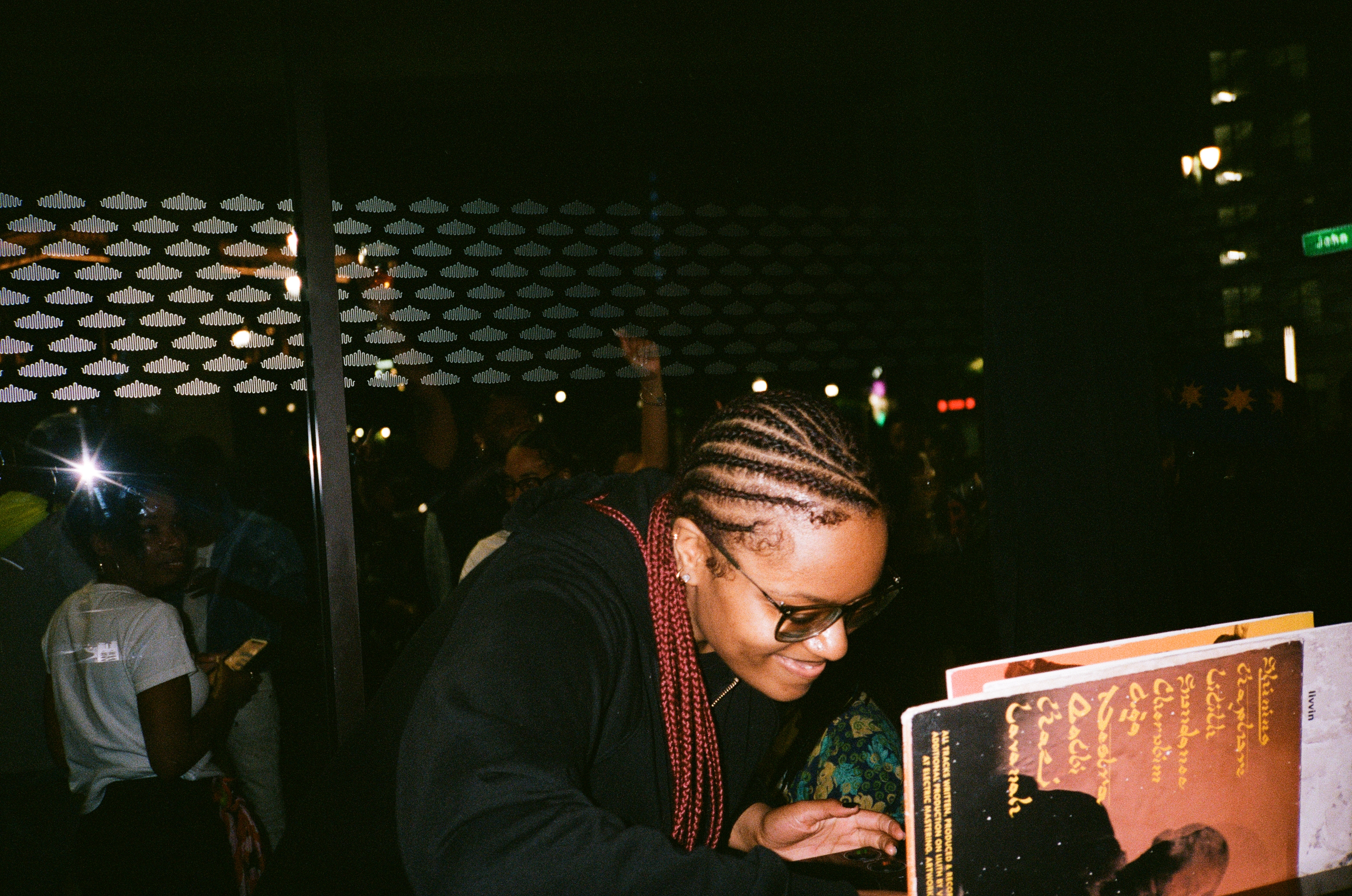

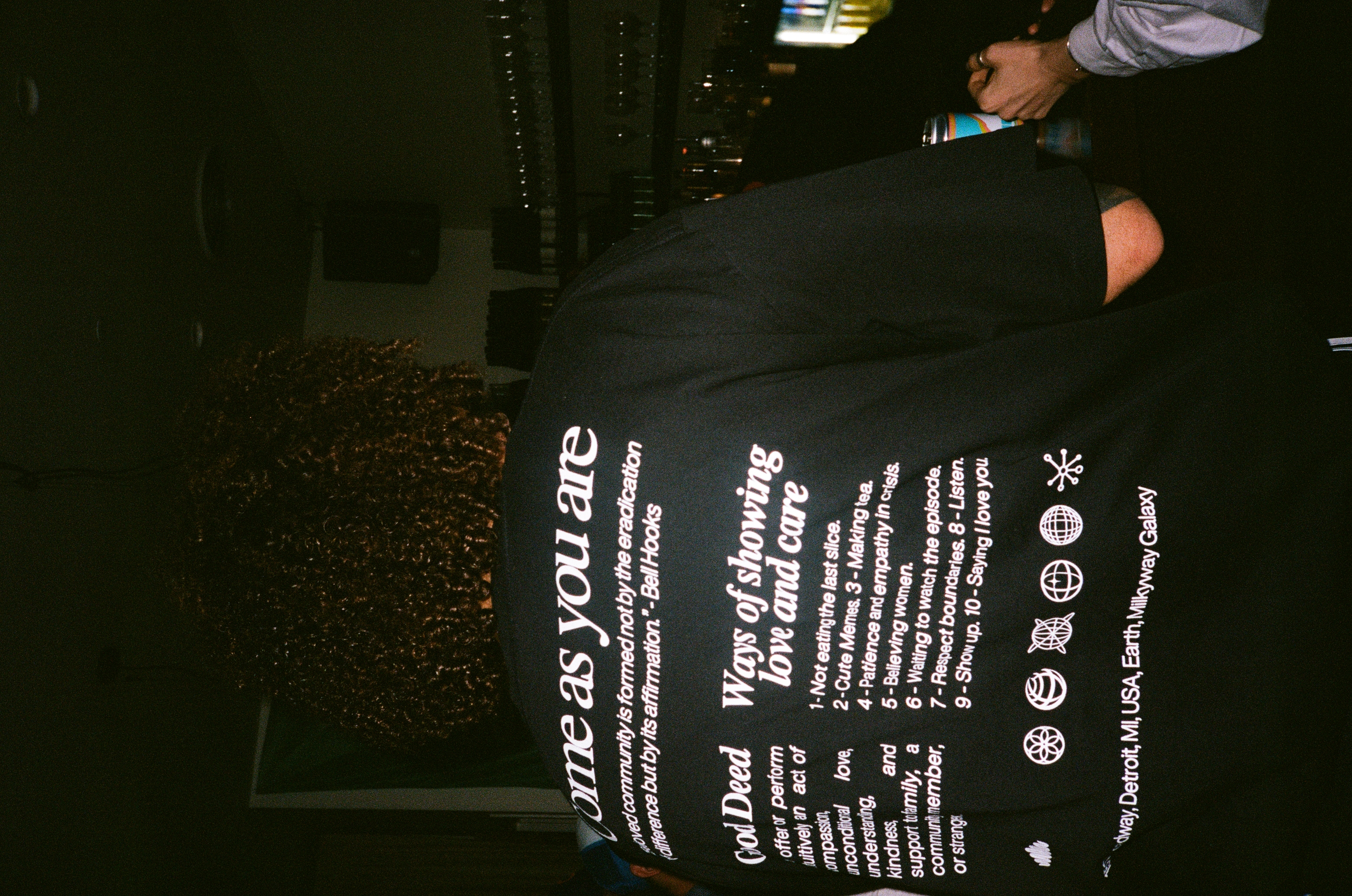

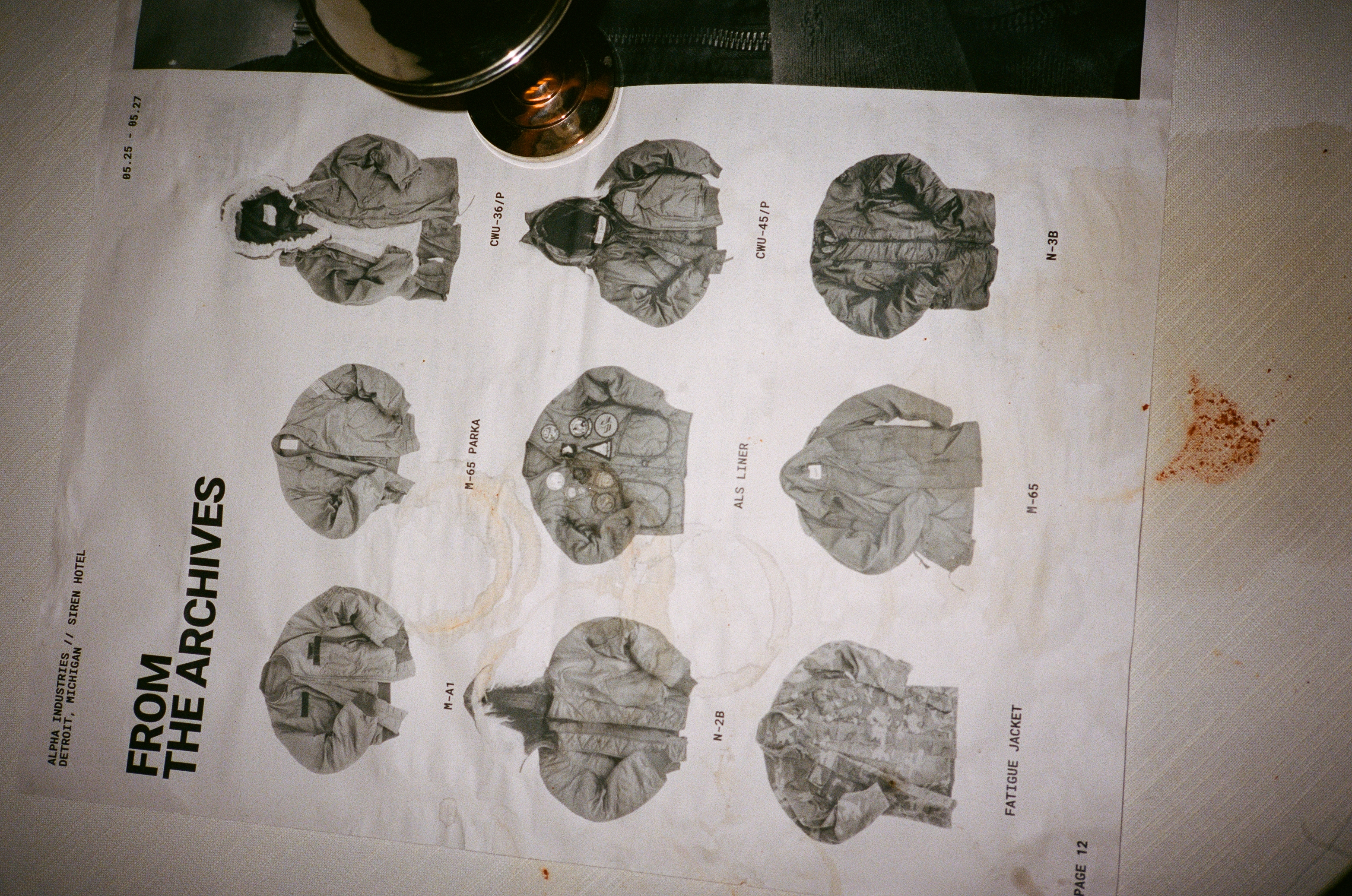

Alpha Industries kicked off the weekend at the hotel’s Ash Bar with a private reception offering food, drinks and DJ sets from WHODAT and Kyle Hall. As midnight approached and it began to wind down, guests made their way next door to the equally notable Paramita, a record store and bar that brought people together all weekend to meet, drink and dance.

Across the four days, guests and visitors were able to shop from a pop-up experience offering exclusive apparel, accessories and commemorative products. Additionally, Alpha hosted a gifting suite in one of the hotel rooms for talent, guests, and friends of the brand to grab a few pieces from Alpha’s collaboration archive, as well as styles from their most current seasonal collection. Amongst the pieces was their iconic MA-1 flight jacket — a garment celebrating its 60th anniversary who’s origin story began as a practical and functional garment for pilots in the United States Air Force and Military but was uniquely adopted in the 70’s and 80’s as an emblem of youth culture.

The parallels between Detroit's music scene and Alpha Industries' cultural impact are unmistakable. Techno music was once considered the epitome of counterculture and an underground convergence of music, art, and fashion; the same subcultures that embraced Alpha Industries as a staple brand in the rave scene — worn by punks, skaters, and hip-hop artists.

Take a look around Detroit and Movement Festival below.