Red Bull BC One

Stay informed on our latest news!

There is nothing more truthful than dance. I told a friend this and her response was, “the body doesn’t lie, it can’t.” Unlike the verbal promises we make with the same lips that are capable of lies, when asked to dance, the body exacts freedom. As we instruct legs to swing, the head to surrender and balance to be kept as we spin, the body rescinds function, leaving itself to keep time with rhythmic transcendence.

As (LA)HORDE — comprised of three artists, Marine Brutti, Jonathan Debrouwer and Arthur Harel — comes off of their two-week stint in New York City having presented two works, Room With a View and An Evening With (LA)HORDE: with Lucinda Childs and Lasseindra Ninja, during the Dance Reflections festival by Van Cleef & Arpel, we are reminded of corporeal power, the multiplicities of trust and what the body is capable of.

An air of transgression hangs over the collective as they opt to use dance as a medium to provoke critical thought, showing scenarios synonymous with violence, rapture and rapture through a labyrinth of choreography. The collective was founded in 2013 and the trio speaks not solely through the language of dance but through the combination of a number of contemporary, artistic mediums, weaving them together, an active writhing. Having been appointed the head of the Ballet National de Marseille in France in 2019, their rise to acclaim is a road paved by lived experiences and the connections fostered by constantly reaching, extending the self. office speaks to the collective, asking them to unearth all the nuances and unsheath their weaponized ideals.

Congrats on Room with a View! It sold out both nights and you guys had two nights of the ballet which also sold out. How are you feeling and what does it mean to be showing in New York?

Marine Brutti— It's definitely a big moment for us. We even had our portrait in The New York Times! We've played everywhere in Europe so we know the European scene very well but given our history and the history of the ballet, it's very meaningful and symbolic to be here. New York is a great place for dance and for the arts in general and what we do as contemporary artists varies so while everything is about dance, our medium is multimedia-oriented. It feels like it’s been a longtime coming as we’ve been working on this for six years. I remember after a show we did in 2017 in Montreal, Jonathan and Arthur came to New York to meet with Jay Wegman, the Director of Skirball, to talk about having the show there. We were still kind of new so they were worried that we couldn’t fill the room. Sure, we had garnered press in the European market but coming across the ocean, it was less palpable. We had no clue whether the room would be full or not in New York.

Lindsey Okubo— New York is such a beast in general and when you say it’s symbolic, what is it symbolic of and does that translate to a sense of validation via understanding?

MB— This is where Lucinda Child’s work and postmodern dance started. Even though it's hard to see the similarities between our work and hers, there’s an expression that says, “you have to remember whose shoulder you're standing on.”

AH— She's one of the major artists who has opened so many doors for artists today. What she did at the time created a major revolution because before that dancing outside with sneakers wasn’t acceptable, it wasn’t okay when she did it. What we take for granted today was actually put in place by artists like her so we wanted to go back to the source, to these points of origin. Because of how the system of culture was created in France, she was able to develop her work a lot in Europe and integrate herself into different ballets across many repertoires.

JD— It’s interesting to go back and explore her own work through our company’s body, for the ballet we took on Tempo Vicino and Concerto. We really feel this idea of the community because so much was created here. Even being able to rehearse at the Joyce studio, we also met with Noé Soulier another choreographer who was rehearsing at Trisha Brown’s company at the Judson school. These are all places for us that feel like the big myths of the New York scene and to get in touch with it engenders a really strong feeling.

Take us back to the beginning where you all met. You guys coined the name LA(HORDE) because you were getting these jobs for and with each other, going out to parties, raves, queer raves and absorbing the energy of these communities. Having seen A Room With a View made me think of the power of lived experiences and their respective necessity to engage with understanding.

AH— It's interesting because I read an interview by Miss Kitten and she was reflecting on her first rave party. She was really talking about immersive experiences, where you enter a space and it's very dark, the music pulses with the light and people are dancing completely freely. They don’t care about their social status, whether they dance well or not, whether they're dressed well or not, it's just a space that they thrive in where their bodies feel liberated. This is the first big awakening you can have in these spaces. Now we're used to it because these aesthetics were brought to festivals and it has been capitalized on but these spaces were where you experienced total freedom.

JD— When we came into queer spaces, it wasn’t only about dance it was about building community, exchanging and exploring our bodies in society. We were young and around people who were on these journeys while transitioning and there were all these questions of what it meant to accept your body? How can you change your body so it is closer to what you feel you are? All the deconstruction we were doing around gender, we realized that it wasn’t a linear spectrum but a nebula and all of these questions around the body brought us to keep that kind of knowledge through our work. These are values that we carry that feed into how we produce work, how we care for the dancers, the stories we put on stage.

MB— In terms of how we met, Jonathan and I were in our school together. We were really focused on performance and video and when we got back to Paris, we met with Arthur. He was a bit younger than us and he already had this autodidact kind of vibe and he was taking classes of theater at the conservatoire, or dancing at Centre national de la Danse in Pantin. We were all active in all of these mediums and practices and didn’t have budget to hire assistants so we were just assisting one another and it was really just like a way of learning what support meant.

JD— We shared everything, money, jobs, and it felt like being hunters, bringing the beasts inside of our home and dissecting them together – this is how we organically created a collective. The collective and its values are about more than how things look on paper, you have to consider the inner workings of relationships especially when you’re making art, it has to be harmonious. It’s a moment that came afterwards for us as a realization that it would be complicated to sign everything with our three names and we'll have to build something bigger than us, (LA)HORDE, and we all work for this house. Even the idea of a house was taken from the vogue scene, who took it from the fashion scene, so there was an active circulation. We were very young and maybe not so aware, it was just something we co-opted that became a part of our vocabulary naturally

This understanding is often the foundation for relationships and a sense of closeness as they’re displayed in personal exchanges, nonverbally. When you apply that to something like dance though, you don’t quite know how a person is going to move, what their body will look like in motion as moved by emotion. As you use dance to comment on the world today, how do you and your dancers form an understanding of value/values?

MB— We really think it’s understanding that dancers have a special sensitivity to the world, meaning that they can have a lot of empathy and share experiences. Not all of them go to rave parties, not at all, but somehow when we're in it together and share this vibe and environment, they all thrive through others' experiences. It's really putting your experience in common, you don't have to go through something to especially experience it and this also goes into how we share things with the audience in the end.

AH— We're like okay, if we get through our own journey in the way that is most authentically possible there is going to be an energy felt by the audience. We also have a very multicultural group who have all had different experiences at different schools and have different approaches to culture.

JD— Our idea is not to give a globalized idea of what humans are, it’s how we can actually thrive on our differences, how we can keep what makes us unique and special and the heritage we carry with us to create a common vision.

I know the term “post-internet dance” hangs in the air around you and a new type of culture has emerged that is untethered to any singular geography, demographic, etc. Ironically, it’s more or less ever-shaped by this notion of borrowing or an active exchange of existing cultures by the internet generations. What’s your stance on this?

MB— So first off as I said, we come from three big fields that are dance, cinema, and contemporary art. Contemporary art has this special aspect to it where this community has a tendency to name things very quickly. I do remember, more than a decade ago, that people came up with the term, “post internet art.”

People act that way as language is the first frontier of understanding and to label is an extension of that intent.

MB— Yes and what is interesting in this term is that it was not coined to define an aesthetic, but it defined a new way of working together. Art has always been about community and when you had movements, it was not because everybody decided to be a cubist at the same time, it was because it was just what they were collectively researching.

JD— When post-internet art happened, the notion of communities suddenly became wider because we didn't have to live in the same place, meet in the same bars, go to the same exhibitions, to be part of the conversation. Artist studios were now on their computers, meaning that it was very production oriented.

AH— I remember when we encountered jumpstyle online and we decided to go further into it and contact the people who were doing these videos to try to understand what it was about. We did that on many different topics throughout our research but something clicked with that community because it was fascinating that it was so niche, it wasn’t viral. We also now have entered a time in which there were these recordings of dance that you never had access to before and the archive suddenly became available and people started to share dance online.

JD— This was the tipping point, we’re not talking about the aesthetics of post-internet dance but more about the fact that this was a new movement. We saw this thinking legitimize itself through platforms like YouTube or TikTok where people began to teach themselves in this way.

Thinking back to what we were saying about freedom in club spaces versus dancing on TikTok where you’re fully just hyperaware of how you look while dancing – has created this overhanging self-censorship. Even when you go out now, people aren’t really dancing, they’re bobbing their heads and looking around. How do you encourage people to be and feel free outside of performance?

AH— It's now hard to experience freedom, collectively. Take for example what they do at Berghain, they have special stickers at the door that go over your camera so you can’t film on your phone. Sure they do it in Brooklyn too and it’s not only protecting the security of people who are inside of these places, it’s about the state of mind that you’re in. Your phone becomes just a device to contact other people, it’s not there to document anything and you have to go through this experience by just relying on your body, soul, mind, of course, but not posing for anything, seeing things through a lens that will be shared with the world in hopes of validation.

In my head there is a big difference between dance and a performance space. Of course, you’re performing when you dance but the idea of performance feels like it’s for someone else and dance feels like it’s for you, the individual. Creating space to do so feels idealistic.

MB— I think there are different moments in a dancer's daily life. For example, when we are in the studio writing a new show, this is a moment where the studio is a very big safe space – and safe doesn't mean sterile – we have very challenging moments where we can explore things that are frightening, heartbreaking, joyful and –

Are you doing this via dialogue or just pure movement?

JD— Both, we set up a situation with rules that follow a very simple dynamic of red, orange and green lights. If there is something that becomes stressful, anyone can say orange. If we’re partnering for example and someone comes and bites me, I can go until a certain point and say red, no, you have to release. We did a whole section where people are putting each other's fingers in their mouths in another show and we wanted to experiment with this especially after COVID because we knew a new boundary had been set with our bodies.

AH— Then when we are on stage, there are different aspects of freedom but everything is written. Freedom doesn't mean improvisation but it's more like a feeling the dancers can thrive on to feel free to actually do these movements because the stage is a situation of transgression. Instead of just going there without a foundation, security, vision or writing, we support them with a story so they can experience it.

MB— It’s kind of like being an actor where if they have a good scenario and direction, they know where to look and what they have to do, they can experience within themselves the freedom of interpretation. Sometimes in dance we think that it’s only about placing the arm exactly where it should placed but even when you look at Lucinda’s work where dancers are doing the same movement, there is a way to be fierce when you do it, to be broken when you do it, to be sad, to be bubbly, these things make a difference and each dancer comes with their own ways of engaging their biases.

Things become more singular too for the performance itself because with the cast of dancers you have, you have individual definitions of fear, sadness, what it means to be broken. In a way I imagine your jobs are to figure out what experiences essentially look “good” together. How are you defining transgression; I think of boundaries but to what extent are those subjective?

MB— I think it comes to the notion that our bodies are not utilitarian. It’s not like they’re just supposed to be a work force used to carry your brain from place to place in the name of productivity. We're trying to re-enchant things a bit by instilling the notion that our bodies can have a life of their own and can participate in society by just being art. The true notion that they can exist outside of time, simply to create an image for us to reflect on, to feel stuff through is already a different use for our bodies that isn’t experienced on a daily basis – this is the first notion of freedom.

AH— Because we have this black box that is shared by so many artists, we don't have the full responsibility to answer the philosophical and existential questions of society and we know that others will come into the room and present their own takes – this is the second aspect of freedom.

JD— The third is that because we're here to look at movement, we can experience how collectively we decided to link one situation to another. For example, in A Room With a View, when the dancers are doing the finger, I remember the first time we did it in Paris, people in the audience were very offended. I had not even thought that they would think that it was addressed to them. We were creating an image, they were giving the finger and when you watch an actor doing it in the movie, you don't feel it is addressed to you but because of what we were presenting, the audience felt like we were being aggressive towards them. It's interesting how people get triggered and can be triggered by forms that are actually inoffensive, meaning literally not dangerous for anyone in the room. Especially when we’re addressing social issues like rape and event the #MeToo movement, people were very reluctant to go through this in France even though we're seen as being the land of love and enlightenment, the patriarchy remained strong.

When we show rape on stage, people are like, “oh my God, it's horrible.” I'm like, oh, I would love for you to find it horrible every time a woman is complaining about it. How is it that seeing it when it's faked is more offensive than hearing victims talking about it? People say our portrayals of it play with boundaries but that’s exactly what it is. It’s not that we’re depicting rape and that’s transgression, it’s allowing ourselves to show things that are important questions and concerns of our bodies in society that need to be asked collectively. Even people’s concerns of having children come to see the show, it’s more so about how parents want to open the dialogue after and it’s their responsibility to decide.

If people not ready, don’t bring them. It’s not about whether it’s for them or not, it’s about deciphering it all. Of course, we put trigger warnings, because we know how it could feel for victims of abuse and it's a tight line but we’re exploring it together. We don't have all the answers and or the dancers, it's very triggering as well. They don’t want to be the people they’re depicting but we manage to present it in a way through a narrative so it is clear that their characters are embodiments of the monsters that we’re deconstructing together.

Why dance can get someone so riled up or triggered is perhaps because when you talk about 2-D art for instance, there is this separation from person and form. Some people opt to define a boundary between identity as an individual versus as an artist but with dance, you don’t have the opportunity to do that because it’s your literal body, you are the canvas.

MB— Yeah it’s living art and by definition it depends on people to carry it through. In cinema it’s the same but you have a recording that freezes in time. Right now, we’re reenacting what Lucinda Child put on in the 70s because we carry the flame so that it becomes part of the history of a different generations of dancers. In dance, we have no other solution than to do this. Of course, we can have recordings and we can mimic but the whole experience of space, time and it has to be re-lived, it’s quite special in this way.

One of the things that I wrote while watching A Room with A View was how trust can be a violent act. There’s a nuanced duality to it and you can see it in these dancers. It makes you recontextualize your concept of something.

MB— Right and even for me when I’m watching it I become shy sometimes because I cry a lot. I cry a lot for so many reasons but it’s really about the generosity of what the dancers are able to give because they trust the work. It’s an enormous gift to us, of course it's there for the

audience but I'm still very moved when I see this manifestation of how engaged their bodies are.

AH— They really want the audience to feel what they feel and what they give, they can never get back. The audience gives back by clapping and the moment of clapping is not only saying you did a great job or validating them but it’s more like, thank you. We very rarely see displays of pure selflessness and when we get in touch with this generosity, whenever we touch this movement of grace, it gives me trust in our humanity. We don't let ourselves activate it so often and we live in dynamics that are written around us that don't allow us to be grateful.

Routine is a chain. One on the one hand, you're giving them a space to tell their story but what is your story? How much do you share with them? Is it important for them to know your background so there is some sort of context for the empathy you have for them or is empathy just empathy?

MB— I think it is, I wouldn't know how to identify it but it’s what united us in the beginning. It was really this idea to give. It's rooted in the first project we did with MPAA (Maison des Pratiques Artistiques Amateures) where you go through a series of workshops and after 80 hours of workshops, you present a work. You have a group of 25 people you can create with and you have to deal with everybody's capacity, possibility, and knowledge of movement.

JD— This time we were with senior citizens, one of them was 84, one of them was practically incapable of moving and so we had to ask, how do you meet the other person not halfway, but 99% of the way? We nurtured this idea of care very much and we understood very quickly that it was really an emulation situation meaning that the more you give, the more you take back. It’s an escalation of good. Because our first projects were with these communities and the dancers were never considered to be people that would be at the service of our vision, we had to understand how to propose a vision to enter into dialogue with them. Sometimes they didn’t want to do things and we had to ask ourselves, how do you create consent? How do you work around everyone's personal boundaries? It’s amazing when they then began to process things on their own, it’s when things evolves

For you personally where does that come from in your own life? Everything more or less stems back to one’s concept of home and even you all have created a home within each other. You must have had experiences that were definitive for you.

MB— Well first, we're three. It’s hard to say because it's enacted very differently in each one of us. I try to expand it more than one person’s trauma that brought them to this and we’re not the only ones to do this. There was a tipping point where we felt the world was changing, even though we couldn't know how much, but we were teenagers when the internet became more profusive. I remember when we were students and YouTube became bigger and you could watch people doing everything or literally nothing in their living rooms. Jonathan and I were like, we’re so fucked. We were studying video and this was art, everybody was going to become an artist – which was great and what we want for society but where did we now stand? This is when we decided to make it our subject, to step back and look at what this phenomena was and the implications it would have in our bodies, in our relationships and how it would impact the way we move. There's this quote by Pina Bausch that says, I'm not interested in how people move, but what moves them. We're just very, very, sensitive and sentimental people and we wanted to find shelter because we felt that we needed protection so we created a house that would protect us.

Protect you from what?

AH— I don't know. The world is a pretty brutal place. When you want to show vulnerability, you have to have a good support system to handle the consequences of speaking out for anything. Even though people are fatigued by influencers or TikTokers, there’s a strength to expose oneself everyday doing nonsense. Because of the distance of being behind your screen, it allows people to be abusive or judgmental. We still want to be able to explore without being shamed for exploring.

In these moments of sharing and exploration you kind of see the nuance in things that we think are universal. Dance is a language but the political and social climates and concerns are different in each demographic. Because you’re showing these issues through dance things like violence, it puts you in a vulnerable place because the audience may or may not feel similarly to you about something.

MB— You cannot predict how people are going to be moved by something so we just rely on our own experiences. If it's moving me, it's moving my dancers, it's moving us collectively, I believe it's going to echo in someone else’s mind. You have to trust the process because even though you're not doing it for the audience – the artwork doesn't exist until it meets people's eyes – We are not making a special formula so it will be easy to swallow.

JD— When Kafka wrote Metamorphose, he was talking about his own depression, self hate and how he became a cockroach in a bed. This book was not meant to be a bestseller but the response was crazy because people felt the same, it resonated wider. It's this notion of sharing one experience, one point of view and realizing sometimes people are gonna relate to it because they feel the same, or they don’t, or they don’t have a clue and they’re experiencing it with other people around them that are reacting to it differently. Even though something’s universal, why? Because we all have bodies? The movements don't mean the same thing in different cultures. You can never really know the power of the image but we know where we create from, we know that for some people it will be more foreign but sometimes a wider vision will give you a more narrow statement and vice versa. Universal is not global and the more specific we tend to be, the more universal we can be because we’re talking about true experiences.

And that’s the beauty of art and why they say art is a selfish act, but let it be!

JD— In times of crisis, I feel a renewal to our vow to do what we do because it's hard time to be able to produce images, especially images of violence, on stage. It’s a very big statement today to ask if we can collectively develop our critical vision of the world and I think this is where art stays something special. It's not analyzing a situation or giving you a proper answer of what to stand for, it challenges you because it's like, I'm showing you something, it's not fucking propaganda, but I'm showing one vision of the world as it is and I'm asking you to answer. In the moments where the audience is lit up for the dancers at the end of the show is this moment of exchange, it feels so powerful to have this moment of connection. The new Punk is to be optimistic for the future.

Nihilism has really taken over and it just allows people to think it’s okay to give up. You don't have justice without violence in one way or the other and sure, there are peaceful means to achieve justice, but you're at war with something or the other. You have to fight for the good things too, even more so.

MB— Nihilism is okay when it keeps you thinking. In his Le Corps Utopique, Foucault wrote that the invention of the ship, is the invention of the ship shipwreck. The invention of the 700 people plane, is the invention of the 700 people crash. With every innovation you have it's come down and once you understand that dynamic, it’s not that you’re against evolution, but it’s understanding the inevitable. This is my only answer today: stay critical. The problems we have are collective problems. It's how we bring our critical thinking together to deconstruct these problems and monsters. The internet offered us a way to do this.

To play devil's advocate a little, what is the role of privilege even in having critical thought. Dance is also one of those things where you also need to have a space to do it, it’s not built into our daily lives and while dancing does feel democratic, art feels democratic, in actuality, so many people don’t have the means, let alone the time or headspace to engage with it.

AH— Yes and this is something you have to deal with. The idea of privilege for me and checking your privilege is knowing where you speak from and understanding where you are when you speak out. To check your privilege is not saying that you're not able to talk about anything, it's just to realize where you stand when you do so and what you do with it.

JD— When we took over the ballet, we knew it was a powerhouse and we knew we had to figure out how to give back this power. We had to stay critical of the system we were moving into and not be taken by its power. The maximum amount of time we can stay directors at the ballet is 10 years, it's not ours, it’s a collective tool.

MB— We're taking care of it for the time we're here so it's healthy when someone else comes in with their own vision and changes everything again and that's fine. This idea of privilege is not about shutting anybody up, it’s knowing how to give back from where you are and how you make the world a better place. It’s not done by giving up everything but if you have power, it’s about knowing how to redistribute it.

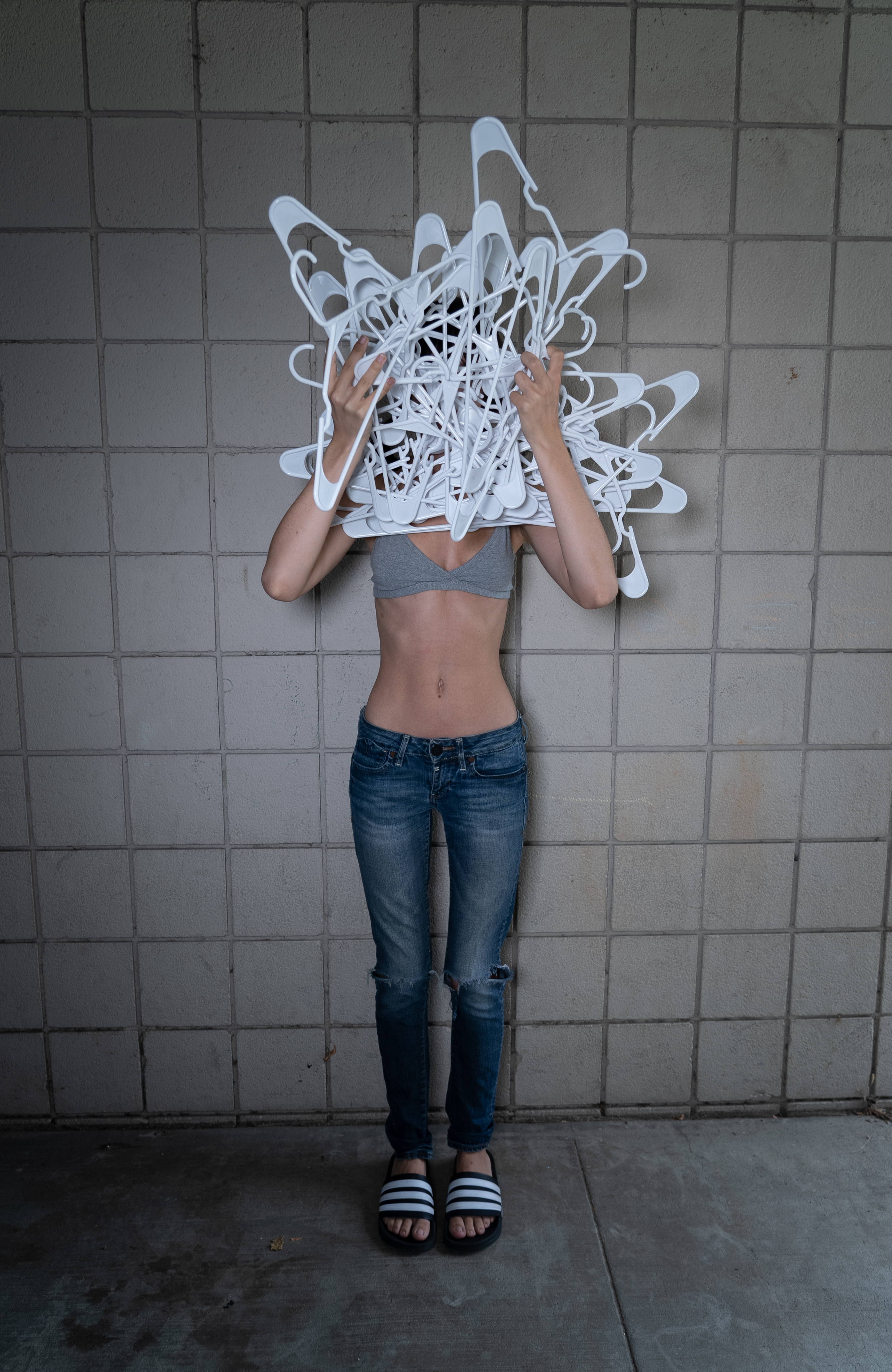

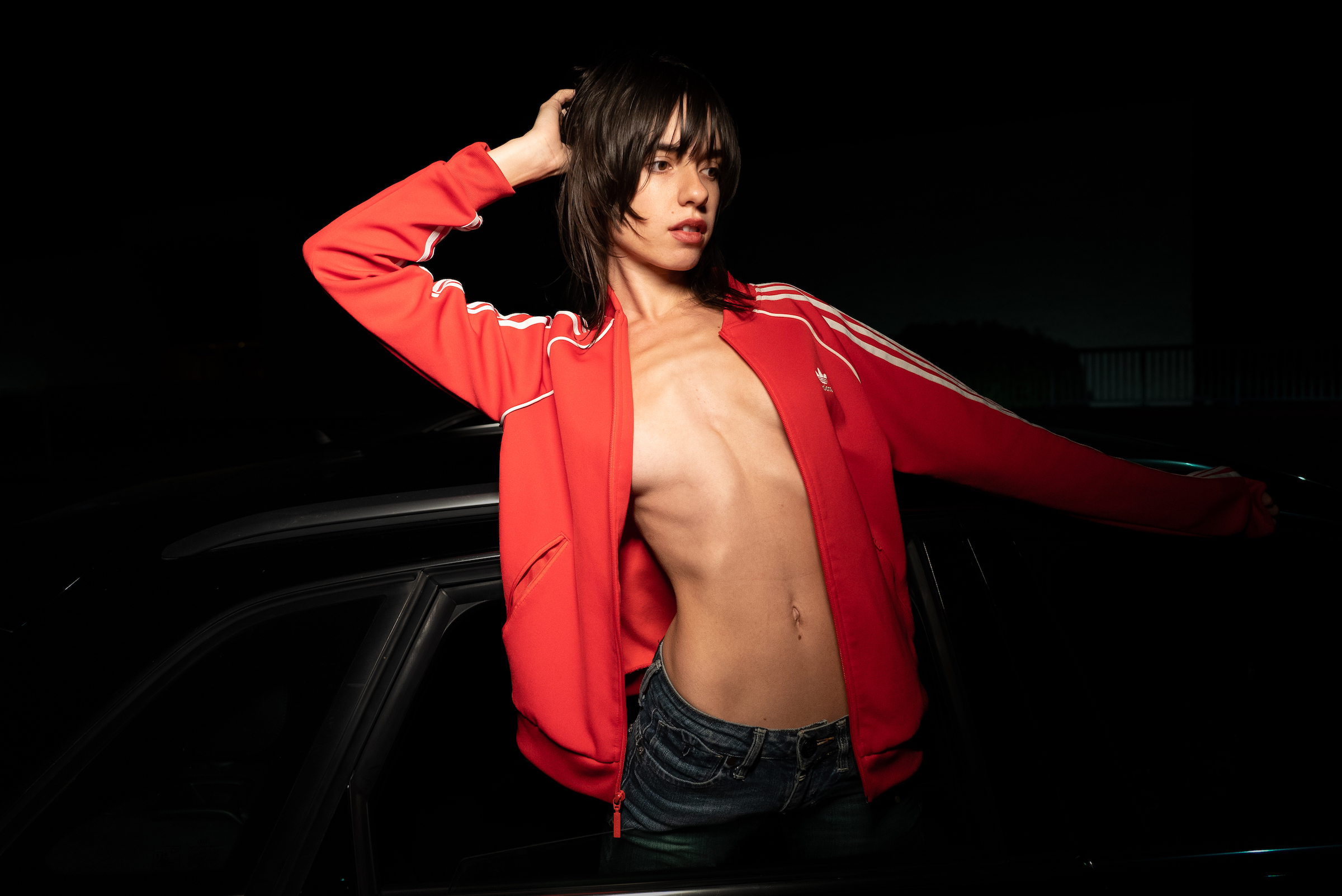

Her selection of subjects is not based on finding those who resemble her; she doesn’t consider herself “moldable” enough. Instead, she’s drawn to people who look like “they could be from anywhere,” with no time or location stamp on them whatsoever.

Ironically, her Instagram account is filled with girls who are almost immediately recognizable — Charli XCX, Emma Chamberlain, Luna Blaise, Chloe Cherry, and Addison Rae to name a few. However, something about Chessa’s lens severs them from their familiar digital identities. Her photographs transcend the immediate recognizability of those verging on the realm of celebrity, offering a kind of invisibility against the objectification femme-identifying people often experience when perceived, especially online.

She reflects on her own digital persona, quipping that “it’s a very weird thing… being a girl in 2023 while also trying to put out art.” There’s a dissonance between these two aspects of her identity, culminating in her instinct to limit how much she showcases images of herself.

Out of Chessa’s 25 Instagram posts, only three include images of her. Of her limited selection of self-portraits, the most recent is an enigmatic photograph of a poster on her bed. On the poster is herself in a black long-sleeve tee and black shorts, posing with a Smart Water Bottle, as if simulating the action of actually laying on her bed with a water bottle. Captionless, there’s no hint or suggestion as to what it could mean, leaving it open to the perception of her audience, which is what happens to her work anyways — being on the internet.

Her photos have even outgrown social media — being featured in magazines and exhibitions — most recently, a cover story with King Kong magazine, and Anonymous gallery’s “Photography Then”, an exhibition curated by K. O. Nnamdie earlier this year. Her contribution to the exhibition portrayed some of the characteristics being brought to the forefront of American image-making currently — a simulation of the past. Chessa’s photography offers a snapshot as to the way in which cultural signifiers are flattened within our screens, rendered contextless and malleable.

Within her work, it’s American references — brands, eras, and iconic moments in pop culture — but rather than capitalizing on what’s trendy, she focuses on what isn’t, the “boring” in our everyday — as in minimal patterns, sportswear, emotionless gestures — enabling the absurd to emerge out of the ordinary.

Like most of us, she’s more comfortable being photographed by a friend, like with these shots Lulu Syracuse took around Los Angeles in the areas they grew up in.

The photos are Lulu's vibe, but also so Chessa's; in them, she could be anyone.

[Originally published in office magazine Issue 20, Fall-Winter 2023. Order your copy here]

What is your ideal office?

My ideal office would be a place with a view. 23 years in the same four walls…. It gets a little boring looking at the same view for that long.

How would your friends and family describe you?

A total ball-breaker.

For you, what is the most sacred place in New York?

The East Village, although day by day it becomes more of a shadow of the place it was when I was growing up.

What is the earliest memory that comes to mind when you think of Fun City?

I grew up in Queens, so my friends and I would sometimes cut school and wander around the city. I was probably 12 or 13 when this happened, but I walked into Fun City just to see what was going on in there because you could hear the machines running from outside. I was abruptly chased out, probably by Jonathan Shaw. All I remember hearing was, “GET THE FUCK OUTTA HERE KID.”

How did you find your way there as an adult?

Fun City found me! I had a couple of friends working there back when the shop was open until 4:00 a.m. I was good for crowd control and talking to drunks at the time.

What was the first tattoo you ever did?

It was a pretty bad chrome sacred heart (which is actually making a comeback).

Do you have a favorite body part to tattoo?

Probably the back — it’s a nice flat canvas.

When was the last time you took a break?

I take breaks all the time since I moved out of New York City. I have really embraced the outdoors through camping and fishing. Simply getting outside is a really good reset button that I wish more people would take advantage of.

What advice would you give your younger self?

Lighten up and don’t be so angry.

Do you have a secret weapon?

If I told you, it wouldn’t be a secret would it?