Red Bull BC One

Stay informed on our latest news!

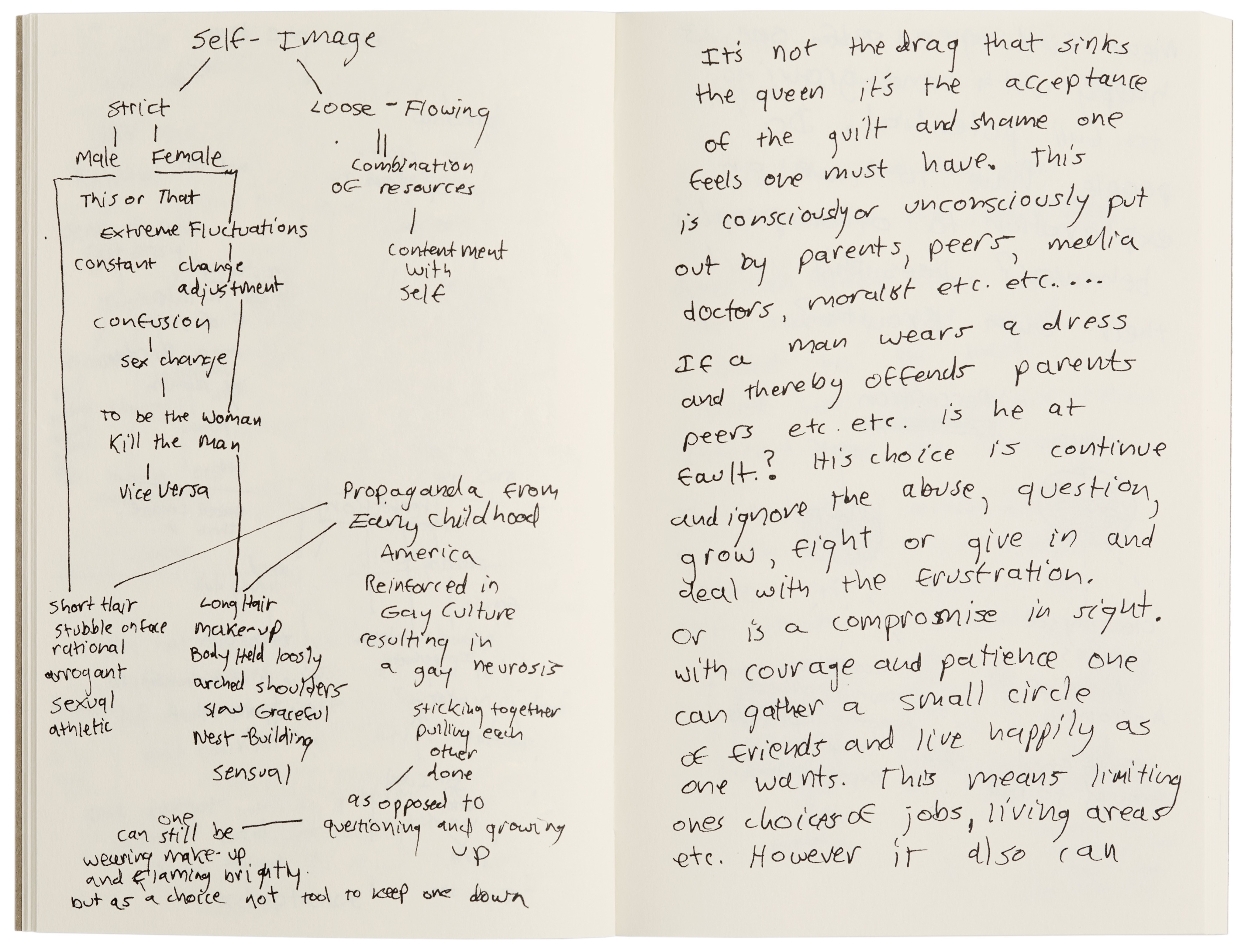

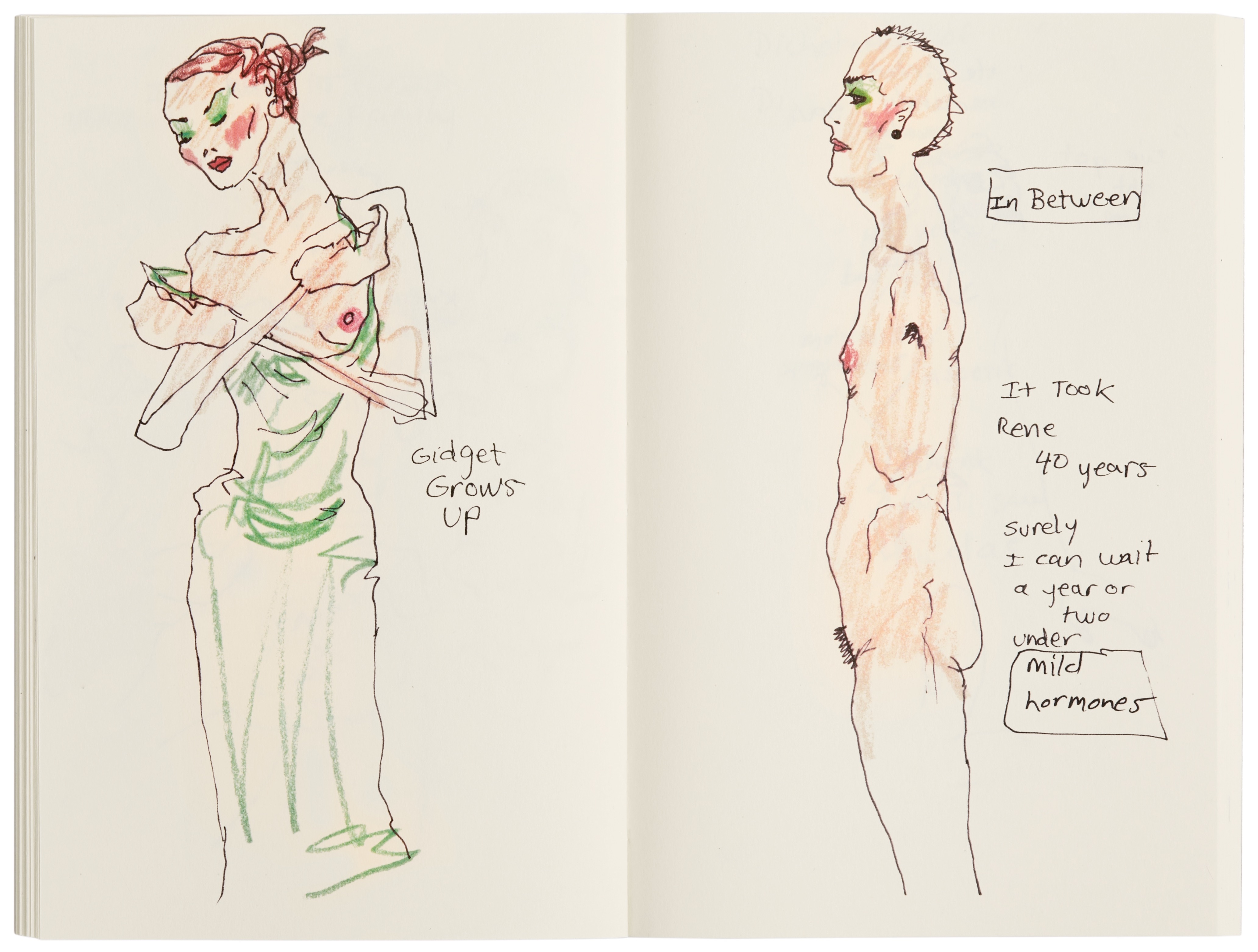

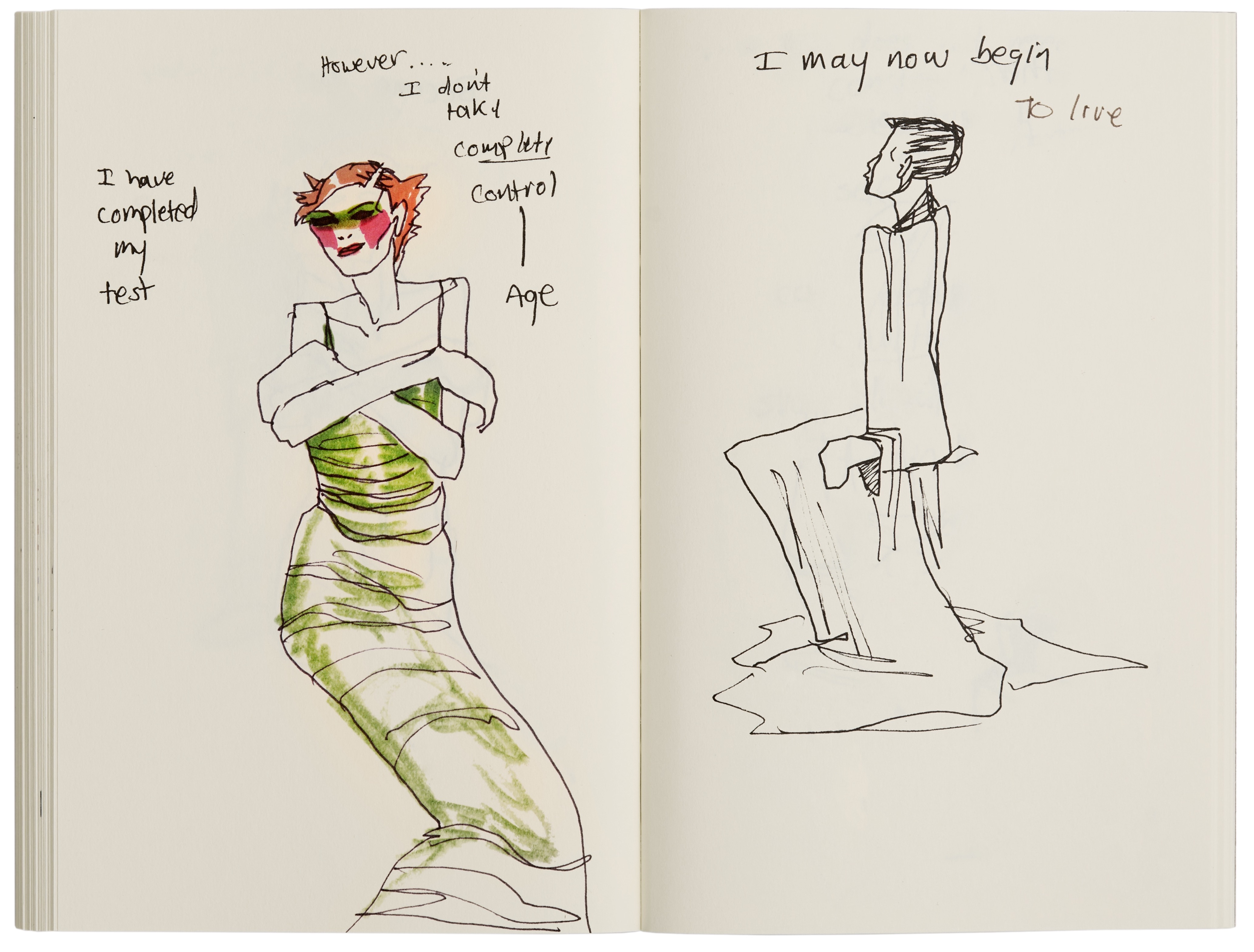

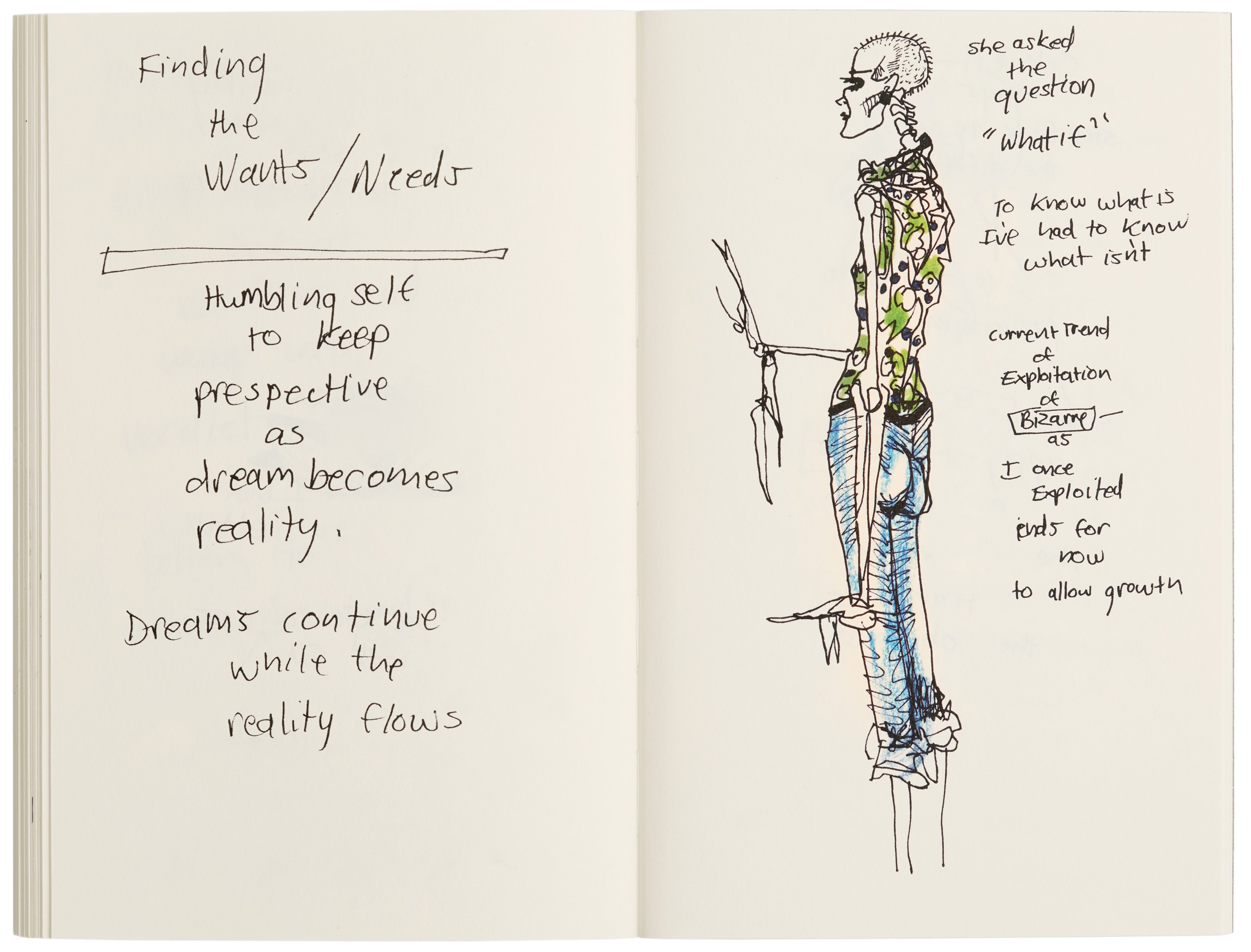

“If you think you have the wrong body, you are always going to think about it,” nineteen year old Greer Lankton pens in her Sketchbook, September 1977. A running theme throughout, we see it questioned and translated through an arrangement of sketches, diagrams, and scattered but mindful musings of a young girl attempting to reconcile with herself. She dives headfirst into deep contemplation of gender, her surroundings, and her inner world. The pages span over two years, beginning just prior to her move to the capital city and leading up to her sex change. In the early stages, she frantically contemplates her body’s inner workings, chronicling her consumption and her battle with asthma in a diary-like fashion. As the journal progresses, it transforms into a collection of etched portraits and depictions of skeletal figures, exploring the possibilities of a social and medical transition.

I initially read Sketchbook, September 1977 in an afternoon or so, unable to look away. Lankton was around the same age as I was when I became distinctly aware of the dissonance between my mind and body, which ultimately led to not only a gendered transition, but an entire shift in my world view once I moved to New York. I felt a tender sense of empathy as she approached the threshold from teenhood to womanhood, a time of whimsy and transformative curiosity. Her youthful longing for clarity resonated with me. Living in a vessel, or “vehicle” as she calls it, lacking a manual is a universal human experience. Yet, reconciling your body and mind as a transexual can be isolating. There were moments when reading her inner dialogue from an era before I was born, rife with heartfelt questions and commentary straight from the privacy of her pen, that left me breathless. How could someone who lived decades ago feel so close? How did she tap into my thoughts?

Many of Lankton's questions can be seen as an expression of her desire for self-preservation, often followed by affirmative sentiments as if she is reassuring herself that it's alright to continue, to survive. She pleads with herself to believe, 'It couldn't be worse than it was... It's worth it.' While contemplating the polarizing commentary and criticism surrounding her life and work, I found this early journal to be a testament to the author's character from a young age. Her pursuit of growth in the name of survival tells the story of a tragically hopeful girl.

Dealing with the unknowns of transitioning, the artist engages in pointed conversation with herself about the proposed material reality intertwined with her gender. Romance, public perception, her relationships and her duties to her body at the cost of becoming… were suddenly tentative to change. Fear of failure and rejection would naturally set in for anyone, and it does. In defiance, she reminds herself gently, “The truth is, I’m alright… there’s nothing to prove.” The latter half of the journal is mostly sketches, exhibiting a medically informed knowledge of the bodily form, nodding to her obsession with the skeleton as we see in the stories she would come to tell in her renowned craft. Lankton seems to showcase depictions of herself in and around many of the drawings, expressive in her continued grappling with what it will take to answer the question of her transsexuality. Nearing the final pages, she states that she will be “free to continue,” and that she has.

This sketchbook provides a prologue to the Greer Lankton the world would come to know. Her legacy has long outlived her in many of her sketches that would later become life-size dolls, inspiring installations filling entire rooms. As I read September 1977, I felt guided by her voice narrating a journey from the metaphysical world into her body, overlooking what would become her actualized form and eventually her life’s work. The detailed insight to the artist’s mind gives way to a sociological and painfully human approach to understanding oneself. “Now that I have a glimpse of self I have caught the glimmer outside of my own body,” she wrote. As her life and career blossomed into a staple presence in the art world of the 80s, we would see many of the fruits of her emotional labor she documented fervently in 1977. This was Greer as she was before her stories were told by others, a girl with the will to transform. I heard her piercing voice as she immortalized herself on the pages, speculation and hearsay falling aside. This was her story.

I’ve said often that transness is a testament to intuition. Led by a profound understanding that our bodies are malleable in nature, we claim agency by assuming the task of evolution. When hearing of Greer Lankton and her work, I was intrigued by the archival documentation of seemingly autobiographical experiences through the crafting of hand-sewn dolls. I saw much of myself in many of them, now with a greater insight into the inspirations of their creator herself. There was an acceptance of her own evolution of body and mind, even if never finished nor always at the same pace. “I will not die, I will become.”

Following the loss of nearly a generation of queer and trans elders in the 80s and 90s, holding her diary feels like an anchor to her humanity, no matter the distance between us. I grew up feeling like the only girl in the world, isolated by my emotions, a belief that was shattered when I met The Dolls. My trans mother once said to me, “You’re not going through anything no one hasn’t gone through before” and it has been a great comfort to me since. Reading Sketchbook, September 1977 reminded me of the same when Lankton wrote above an outline of what seems to be a version of her own face, “I may now begin to live as others have before.”

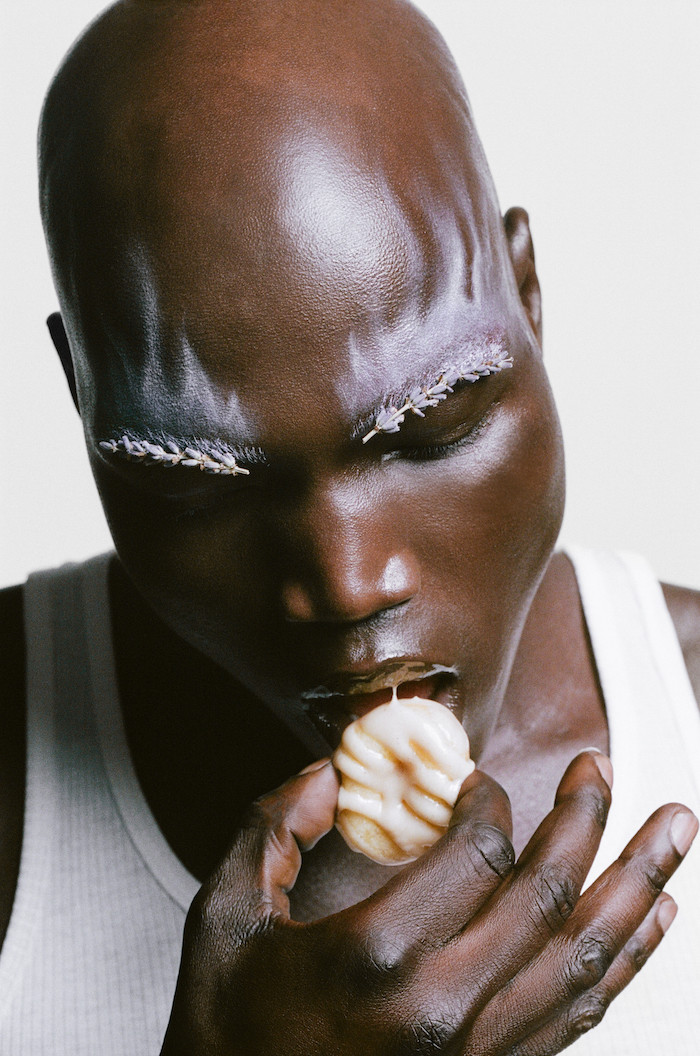

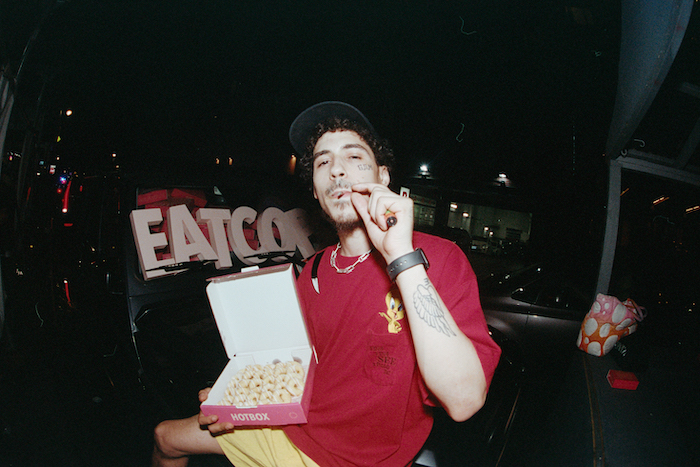

“We believe we're destined to inspire the world around us. We want anyone in fashion, design, or art to look at what we're doing on a creative level and be inspired,” White continues. Aside from purveying delectable mini donuts, which come in two classic cinnamon sugar and sour cream flavors, COPS also champions local creatives within all different scenes — from working with NYC-based spatial designer Christine Espinal on a one-of-ak-kind event installation to Toronto-based designer Spencer Badu for an exclusive uniform collab.

Acting as an artistic outlet for the COPS team, they also introduce one custom weekly flavor, orchestrated in partnership with a food scientist and fine dining chef. “We also worked with another fine-dining chef last year; his name is Brandon Olsen. He curated a bunch of our weekly feature glazes, so the plan is to work with multiple chefs from around the world on different glazes, showcasing their capabilities and their own flavor profiles,” White expands.

Whether they are hotboxing a G Wagon outside of Soho House or curating event installations around the world, COPS is sure to bring the heat no matter what boundary they decide to push next. “Anything can be art if it's placed in the right setting or in the right context — and if the storytelling is right. It's just a matter of romanticizing it. We ultimately want to curate this awesome community of creative connection,” White concludes.

Surrounded by go-getters and artistically-intuned family members, Jordan built his creative foundation in Toronto by dabbling in underground circles. Starting in 2019 through experimenting with art, fashion and styling, he quickly realized music was always an underlying outlet he returned to. Today, he is known for curating global sound spaces for Caribbean and POC youth of all expressions, spanning New York, Miami, Los Angeles, and London. His most recent endeavour was a partnership with photographer Micheal Grant to capture the intricacies of Miami Carnival through the lens of a sound curator, emphasizing the representation of all walks of life. The byproduct of Jordan's music curation is profoundly animated in the photographs through vivid colours, textures, shapes, and spectacles, chronicling the unapologetic essence of Carnival.

How did you emerge into the sound curator space?

I don't like to call myself a DJ and prefer the term sound curator because I create different forms of sound in many different ways. I started interning with fashion brands during New York Fashion Week and saw that many models were also DJs. I wanted to see how I could venture out of fashion and do something more innate, like music, which was around me my entire life. My brothers were promoters and always brought their DJ friends around the house, so I was exposed to the work early on.

I spent a month in October 2019 in one of my friend's houses, which had a full DJ set up, and I would go there after work every day and learn. I don't want to say it was destined to happen, but it was always a facet that was around me.

Tell us how attending Carnival has shaped your experience and development as a sound curator.

Growing up, Soca music was always playing in my house; it's always been around me and backdropped my life. Carnival was a space I attended year after year with my family, and It's a part of who I am and my identity. It feels like home. I love wearing my costume because it takes me back to that feeling I had as a kid.

What one Carnival experience stands out from the rest?

One of my most monumental carnival experiences was a memory of running across the stage and dancing in front of judges at Trinidad's Carnival this year. Being around a group of people and being strongly unified was such a beautiful feeling. We all channelled expression through a costume, no matter your appearance or background. This year, when I crossed the stage, it was our culture's prime time of celebration. Nobody is not smiling; it's a feeling everyone waits for.

When did you and Michael Grant meet, and how did the photography collaboration materialize?

In 2021, I met Michael Grant in Atlanta. I always appreciated his photography work and how he provokingly illuminates the portrayal of the black experience, intersecting class, family, and relationships through subculture. Although we went our separate ways geographically, our hunger to collaborate still lingered. Fast forward to October 2023, we were in the same place at the same time and naturally fell into collaboration.

What did you want to showcase in this project?

I wanted the project to capture Miami's Carnival through the lens of a sound curator. His camera was essentially my eyes. He was capturing moments I wasn't exactly seeing but felt. Across 12 rolls of film, these snippets were happening around me, and I knew they needed to be documented to display the true nature of Carnival. Initially commissioned for two hours, he stayed the whole day, leaving at 10 PM.

Before any photographs were taken, I wanted to emphasize and ensure all forms of blackness and all identities were spotlighted in the carnival space. If Michael saw a guy twerking, I wanted that captured. I desired impactful and vulnerable shots that accurately captured black culture from all experience perspectives. I wanted the uncut and raw parts accentuated because, as a DJ, that’s the parts I stand for.

Why is it essential for you to illustrate Carnival through this perspective, and how does your music shape the experience?

At Carnival, the Caribbean community acts, dresses and maneuvers the space with an energy of celebration. It's a sense of liberation and a space to be ourselves freely. Carnival is the one day of the year where people can exist without limitations, so I'll play the music that ignites that spark and channels who they are. No matter the gender identity or background, you'll see all walks of life dance to the Soca and Dancehall songs I play. I'm creating a sense of unity and celebration through sound that the black community can enjoy.

What does the future of Caribbean sound look like to you?

I see the Caribbean sound expanding worldwide with a very natural growth progression. It's already on that journey, with Caribbean creatives gradually pushing culture in any way they can. In reference to the African community, we've seen how they've been successfully spreading their sound and culture with different forms of regional music. I see exactly this happening to Caribbean sound and culture as well. It's in the hands of Caribbean youth to push this wave, and once people get more acquainted with the sound, Caribbean culture is only going up.