I read that at 28 (nearly how old I am), you laid out all the covers of Dazed you shot, put them on the floor, and thought to yourself, how good your life was. After shooting so many icons, what is it like to revisit those early covers? Does it feel nostalgic? Do you feel more critical of your past work, or mostly proud?

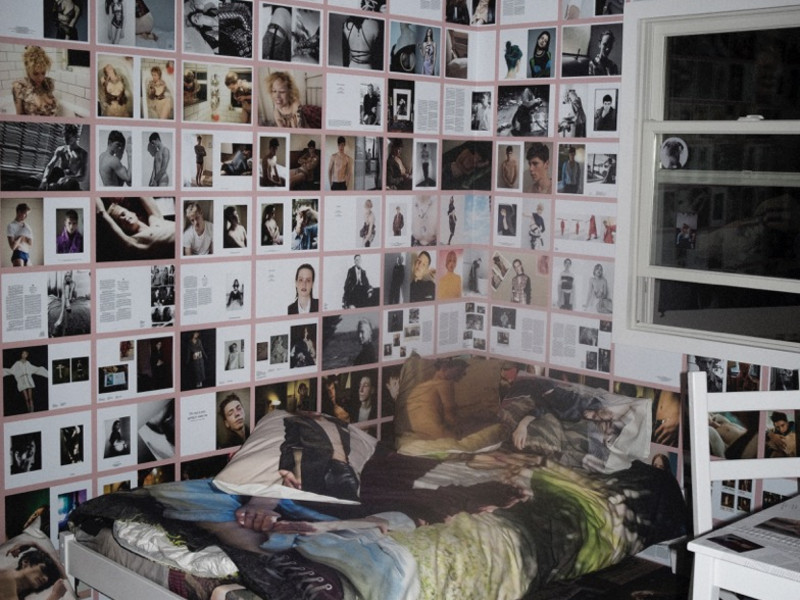

Good question; it changes a little bit. I did a book six years ago about the work from Dazed called Unfashionable. It combined my work in fashion, art and photography. When I looked at that work, it was quite basic technically but I was surprised it included the same themes. The human condition, the manipulation of imagery and media, the idea of taking celebrity and trying to democratize it and make it more accessible. I'm fascinated by the seduction of fashion and trying to make it more human. Those have been the same themes in my work for 35 years. I didn’t think that — until I looked back and went, “Oh God, I'm still banging on about the same stuff.”

Of course, I'm critical. A lot of current work lacks critical thought behind it. I don't mean that just in terms of looking at it and thinking “Is it good or not?” but thinking, “What's the meaning of it in the world?” When critical thought is in the work, you can feel it, \you don't need to ask. It's in your face. I've got that. It's built into me. I'm a 51% positive, 49% critique. You criticize me, I've already done it.

But I've enjoyed putting [the retrospective] together and looking at all the collaborations. I took them for granted then, but now I see how special it was. So many people in the photos or contributing to making the photos came to the show and it was overwhelming to see them all there. I’m not in touch with these people all the time, giving the work credibility beyond me and my relationship to it. I'm frustrated I didn't have a better relationship with some of my collaborators, but that's the arrogance of youth.

What’s it been like interacting with people at the retrospective who haven’t been reading Dazed for the past 20 years? It’s a magazine for youth culture but a lot of 18-25 year olds weren’t even born for these issues. I would love to know what it’s been like for you to witness their reactions to your work.

I have to be honest with you, I haven't really watched people look at it, but I’ve seen the social media response. I use social media to represent my work, not represent me so I'm not constantly on it, being performative. It feels like talking into a vacuum, but it’s been fascinating to see people post about [the retrospective]. People have their favorites and there's something affirming in that. The age range of people reacting to it is broad. I made this work when the magazine was distributed to 5,000 people. By the end of the 90s, we reached millions of people. But by that point, I was drifting away. Dazed was becoming less political and more commercial as a fashion and style magazine. I was more interested in changing things.

What was it like to watch Dazed become something on its own? Do you still feel connected to the magazine?

No, not really. But the ethos now is very similar to the ethos at the start. When we started, myself and Jefferson [Hack] made an agreement that we wouldn't be the editors once we felt like we weren’t the target audience or relating to the target audience anymore. We always said that you should make a magazine for yourself, not for your audience. Then the audience will come, but the minute the audience isn't relating to you, you need to move on. That's why he started AnOther and I started Hunger Magazine.

If you said to them I left because it became commercial, they'd say I was the person that was good at making money and commercialized lots of it. We sold the back cover and I would shoot it. That was completely commercializing but we did it in a unique way nobody had ever done before. Back then we were about creating culture, creating moments, creating what I guess you'd call “breaking the internet.” We were never about reporting or taking photos of culture. We were making it. We started Dazed to be a platform to voice independence, unique thinking and youth. I love it when it still does stuff like that. I'm proud and jealous all at the same time.