Mythology is central to the series. Where did you draw inspiration from existing folkloric legends, and which symbols and motifs arose from your own experiences in the world?

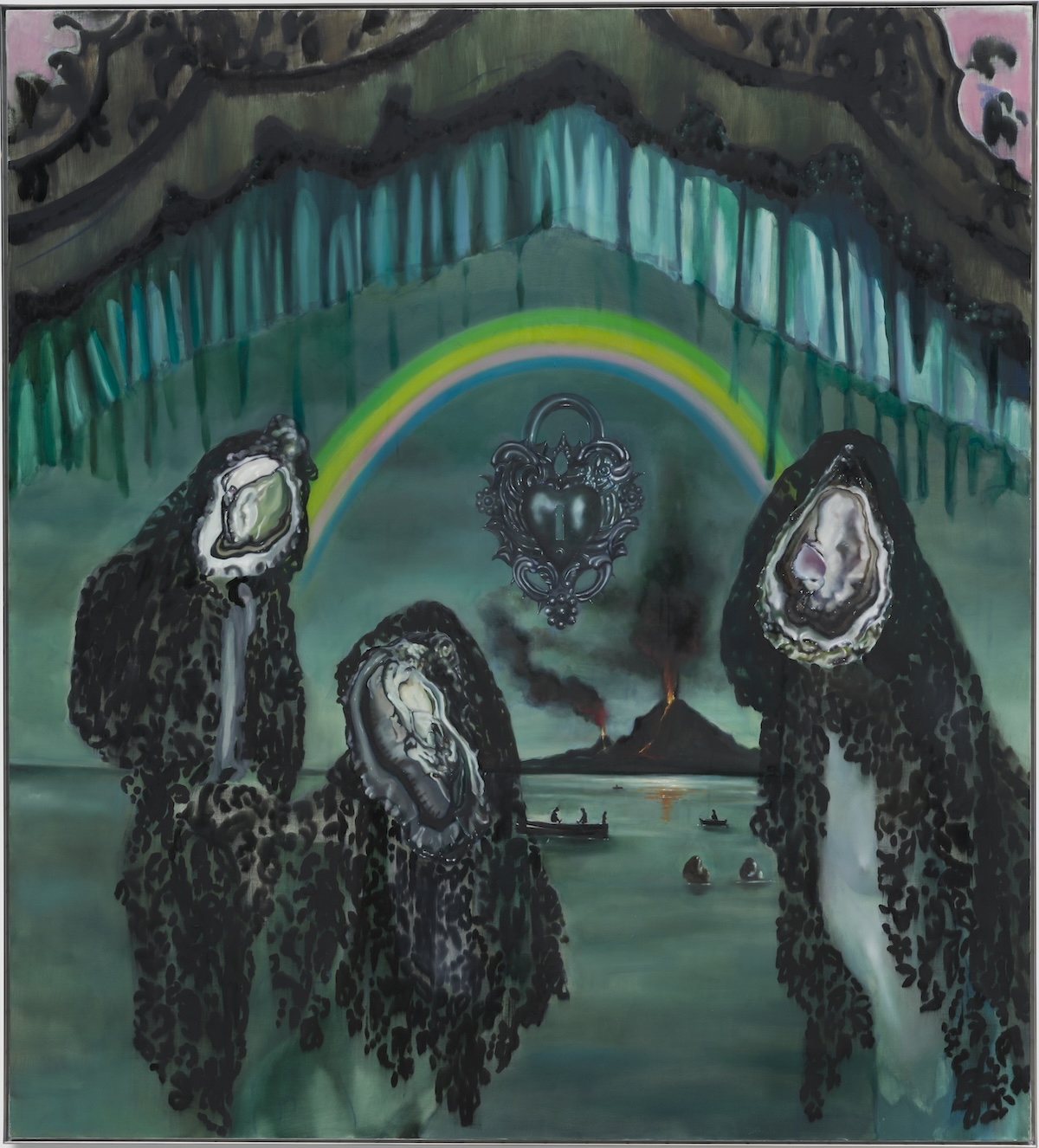

At one point, I was in Greece and I was going to quite a few caves. Some of the most profound, mesmerizing experiences I’ve ever had have been in caves and cenotes. It’s this primal feeling; it’s womb-like, it’s elemental, it’s ancient.

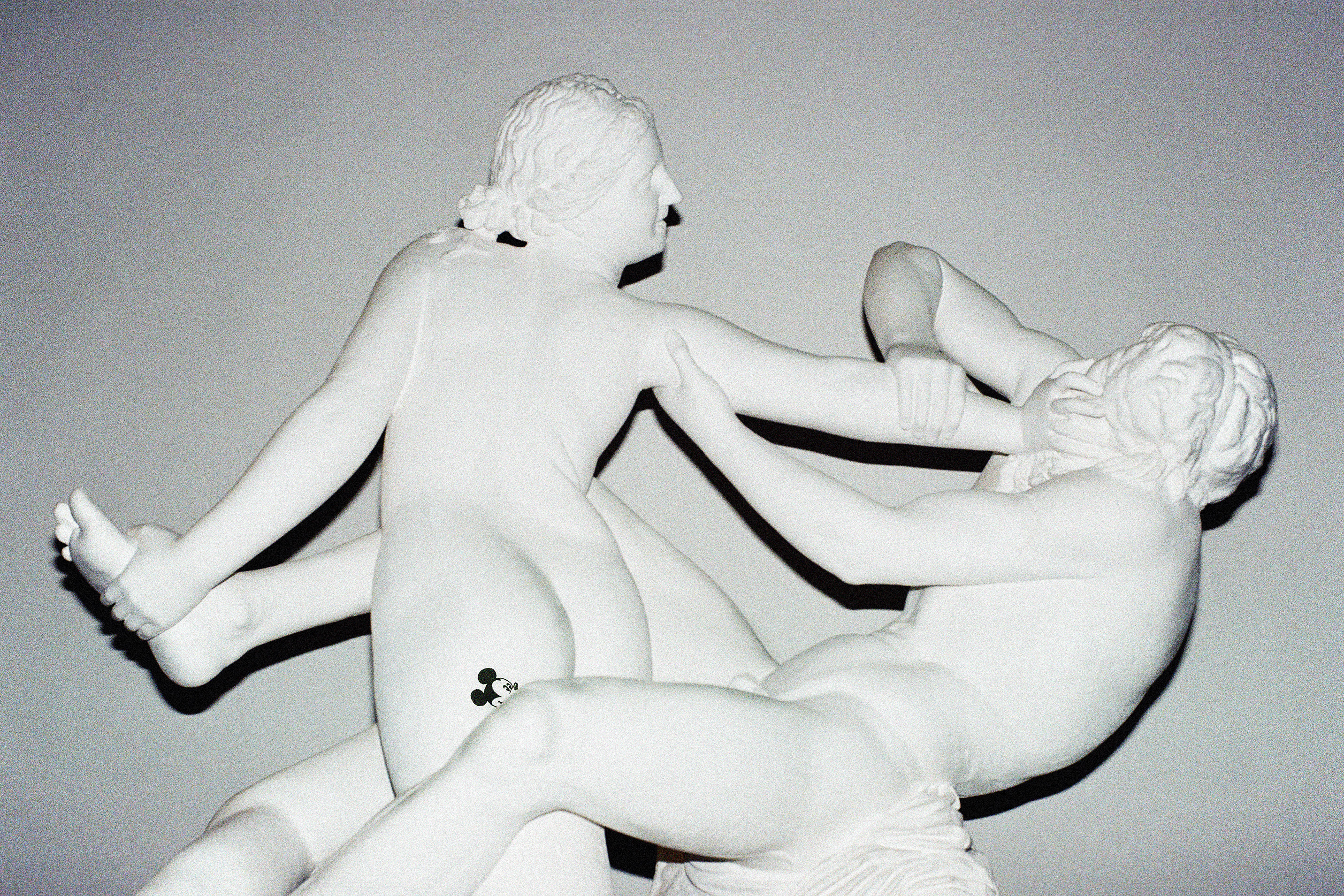

I love this notion of the great return, and I symbolize it with shells, with water, with oysters—which, of course, could be interpreted as female anatomy. It’s like the birth of Aphrodite; it reminds one of coming back to the ocean, to water, to the womb.

Tell me about the books or historical sources that inspired your approach.

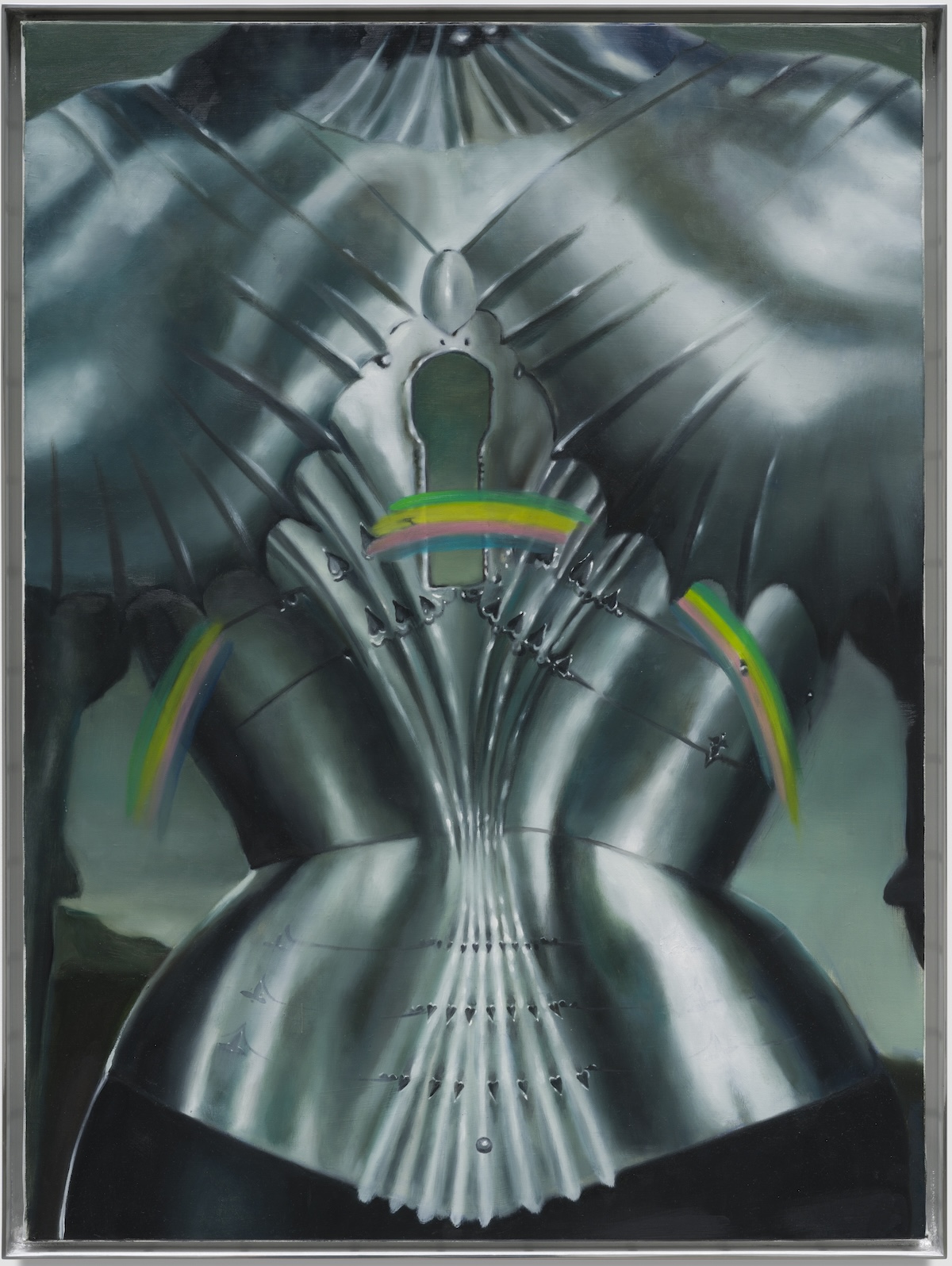

There’s this very large, very old book from 16th-century Germany called the Augsburg Book of Miracles. It’s full of gouache paintings of very surreal apocalyptic scenes. There are comets, there are swarms of locusts, there are strange mythological creatures, there are images where it’s raining flesh and blood, there are rainbows. It just has this sense of mysticism, wonderment, and total unease. Nobody knows who made the book—it’s a mystery.

I also read a book called Medieval Bodies, and learned that in the middle ages, there were a lot of interesting parallels being drawn between human body parts and parts of nature. The lungs are like the wings of a bird, symbolizing flight, breathing, movement, and life force. The nervous system and the brain are like tree roots. It goes back to this kind of external, internal relationship between nature and the human body. So I think that’s also where I got a lot of these motifs of shells and barnacles and metamorphosis.

How much are you consciously crafting these layers of meaning, and how much of the work is free-associative?

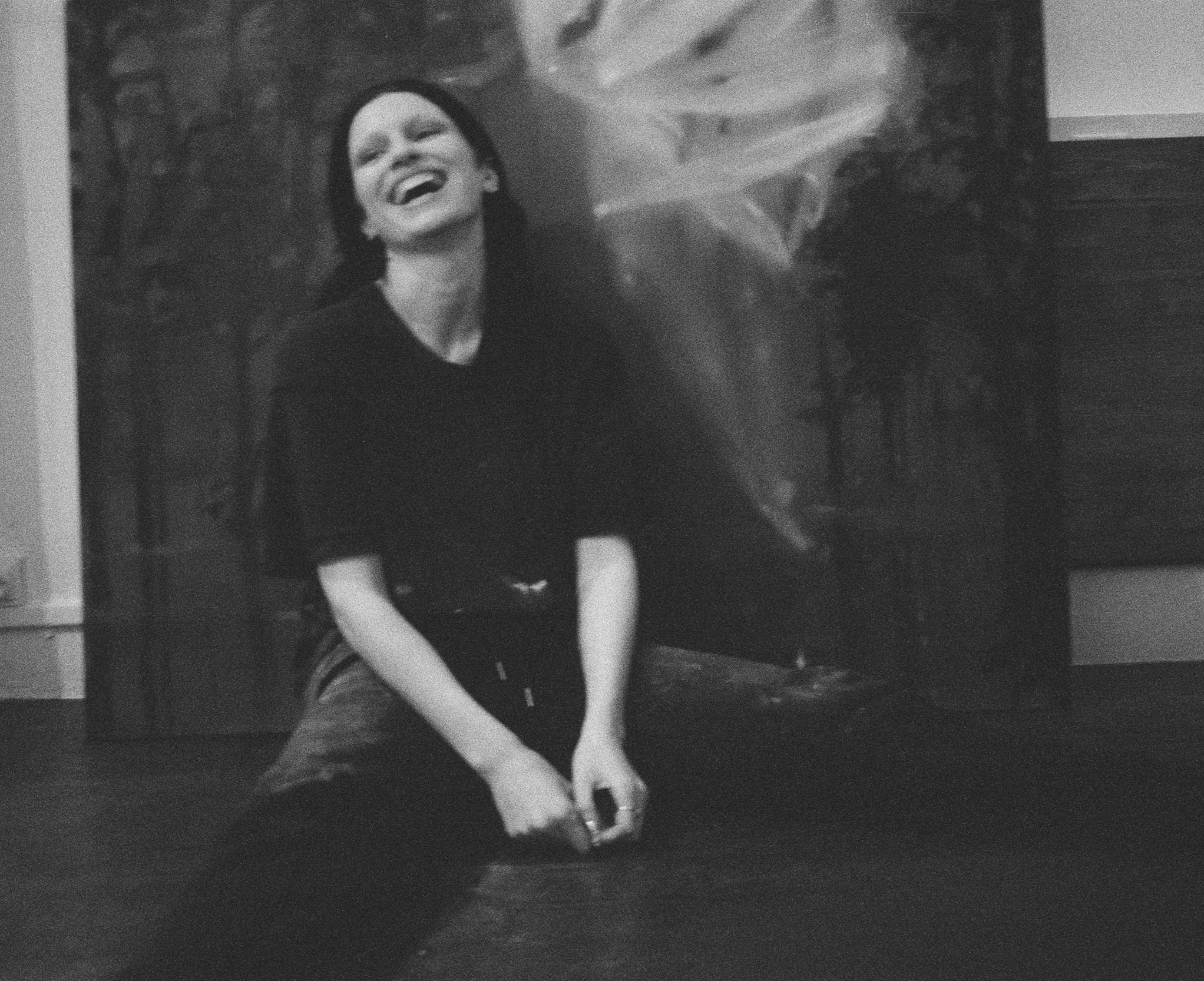

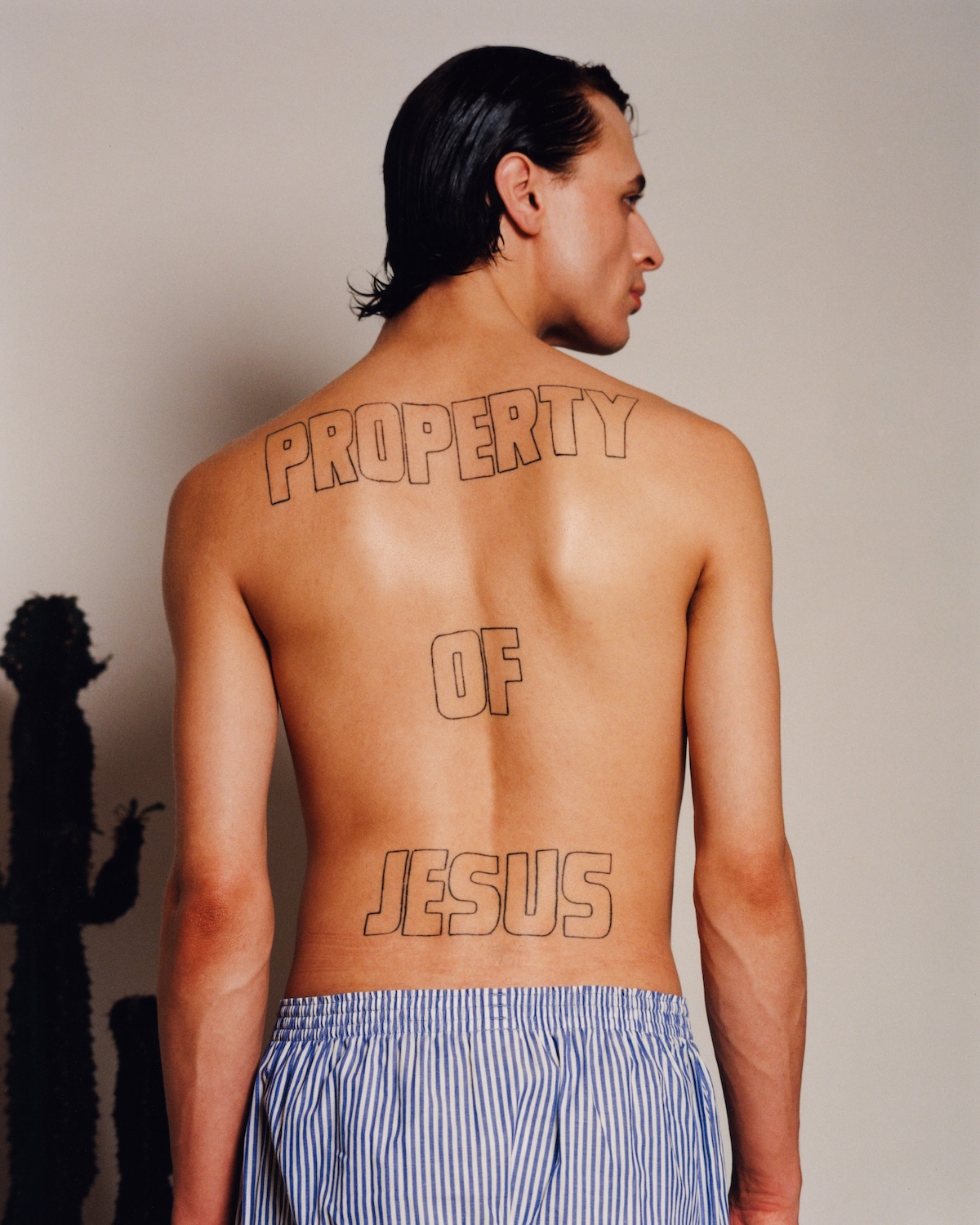

I’ve never wanted to create paintings that make people feel one singular thing. I think it’s fascinating to let people go on their internal journeys with what these symbols might portray for them. There is a meaning behind everything I do, so there are lots of little doorways to open if one pleases. It’s like a secret within a secret.

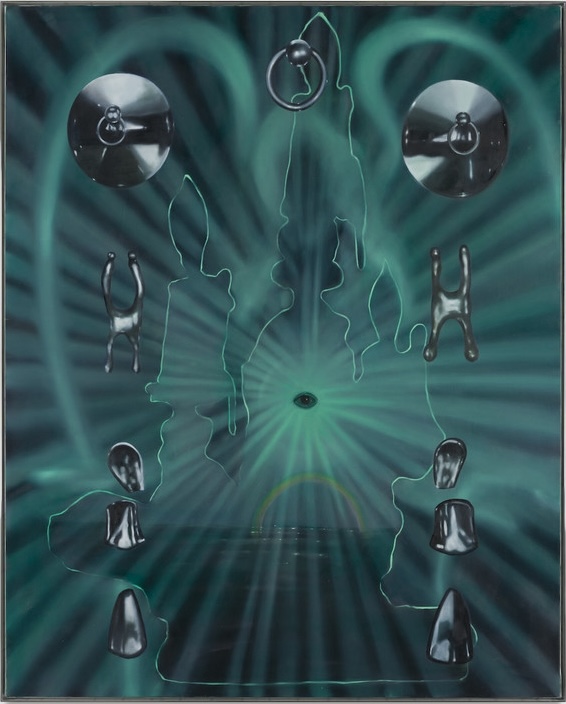

For example, Touching the Vessel, that painting with the silver metalwork, is a reference to Betony Vernon’s jewel tools. To me, the work she does is like a metaphor: she’s making these beautiful objects that allow people to erupt in a sense, to open, to break through. These objects are like a symbol of physical transcendence. So they were a metaphor for orgasm and out-of-body experience. And I love that the same motif that conveys disaster and chaos can also be a symbol of pleasure and transcendence.