Check out the photos and interviews below.

Stay informed on our latest news!

Stay informed on our latest news!

Check out the photos and interviews below.

A short introduction of your origin and ethnic/cultural background:

I was born and raised in New York City. My father is a fourth-generation Italian American from the Bronx, but he's originally from Sicily and Naples. My mother was born and lives in Taiwan. They met in New York while she was getting her masters in dance, and they both participated in an interpretive dance piece by a mutual friend.

What type of work do you do in the creative industry?

I am a creative director. Three years ago, I started the book series FAR–NEAR, aimed at broadening perspectives of Asia through image, person, idea and history to unlearn the inherent dominative mode. We feature artists, photographers, writers and other creatives from Turkey to Japan.

How does your identity influence the type of work you do?

I've always felt like an outsider-insider to both the Caucasian world and the Asian world. It's made me doubly more interested in interactions across boundaries, and ensuring that any commercial or creative project, for that matter, is informed and reaches deeper than the surface.

How has your family/community responded to your path?

My father has been very supportive throughout my life to reach for something creatively driven, though I chose my own path, which is what I do today.

What are some of the challenges you face being a creative in NYC?

In some cases, whether it is because I am a female, physically identify as a person of color, or if it's just because I'm relatively soft spoken, I've had to push hard to get my voice heard. Sometimes it has taken more than several times of my repeating the same concerns over a concept or a project or a casting, before it is taken seriously. I think it's important for everyone to listen to what each other has to say, and to understand that some people have more jurisdiction over certain topics based on first-person experiences.

What are some aspects of the industry you would like to see evolve?

I would like to see people reach farther than skin deep. It's disheartening to see commercials or mainstream media representation, even niche representation, settle for stereotypes to "fight stereotypes" or keep people in boxes without them realizing it. One day, I hope we can express ourselves and have the opportunities to control and explore our own representation across different media—not just be a face, but also a voice, a person.

A short introduction of your origin and ethnic/cultural background:

I was raised in Ann Arbor, Michigan. My mom is Chinese Malaysian (from Teluk Intan), and my dad is African American (from Memphis, TN).

What type of work do you do in the creative industry?

I am a photographer and a creative. By creative, I mean that a lot of my work history is in working with brands on the ideation, writing, and creative execution of their advertising work with supporting roles in art direction and film direction.

How does your identity influence the type of work you do?

I don't think our identity can be stripped from anything that we do.

How has your family/community responded to your path?

I had a lot of trouble in school growing up, and I was very unhappy. I know that a lot of my teachers and peers didn't understand what I wanted, because I didn't either. I was really distracted and destructive, even though my life maintained a lot of structure thanks to my parents, their resources, and especially because I was able to maintain a life as a high-level competitive athlete. But I think there was certainly a point where my family kind of put their hands up and were like, "Whatever happens, happens. We've done everything we can for her." I am so lucky that I was able to grab onto my support system and what was left of my dreams or inner motivations and pull myself into a place of happiness, inspiration, and productivity. I could not have done that if my parents did not emotionally support me through those really dark years. I truly think that not just my immediate family, but my community that I grew up with as well is relieved just to see me do something that is right for me, that I've found any sort of success or ease with, and that makes me happy. This path is very different than what my parents have done with their lives or probably hoped their kids would do, but I know they're proud just to see me be okay.

What are some of the challenges you face being a creative in NYC?

Lack of time, lack of financial resources. Sometimes I feel that there's too much pressure to go out, meet people, and be social, and I find it quite distracting from my purpose. The lack of time and money mean that it's impossible to dedicate yourself to your own education about your medium, to make the bad work in order to get to the better work, or to really spend time with your community. I have spent the last five years in a full-time job while also building my career as a photographer, and that has really vacuum sealed my life from any sort of freedom to fuck up or push myself and my work. I find that really tough. I don't want to make images that look exactly like the images my peers are making, but when you're using social media as your inspiration outlet, because it's so fast and so accessible, it happens. I find the biggest gift I can give myself is time doing nothing. As a full-time freelancer now [as of one week before the quarantine started], I can decide to give myself that.

What are some aspects of the industry you would like to see evolve?

First and foremost, I would like the industry to be more conducive to peer-to-peer education and support. I don't mean that we need any more panel discussions—just that I hope we can take more time to talk with one another as fellow artists even if we're all basically competing for the same jobs. It is so crucial to have someone you can go to and be vulnerable with your questions about how to do things, for critique, and for some praise at times too. It is embedded deep within me that encouraging and celebrating others is a keyto your own happiness and fruitfulness.

Secondly, I want more Black, Latinx, and Southeast Asian female photographers, designers, directors, DPs, producers, and writers in general. We need more of us, ASAP. To that point, I think it can be easy to feel like things are really changing, becoming more diverse. But in reality, the people who are most praised, given the most serious accolades/opportunities, and the loudest voices are usually men. And again, I don't necessarily think more branded panels or female-only workspaces is the key to fixing that. I don't know what the answer is, other than just taking note of it and continuing to grind just as hard as we've always had to for half of that attention or regard.

More free classes and education! More true and real pathways for young people of color and low-income people to get into the technical trades on set.

A short introduction of your origin and ethnic/cultural background:

I'm a queer Bangladeshi Muslim femme.

What type of work do you do in the creative industry?

I'm a multidisciplinary artist.

How does your identity influence the type of work you do?

It seeps into everything I do. How I perceive the world, how I process it—and therefore how I synthesize my thoughts into my work. Everything that I've experienced I've sublimated into storytelling, and in that sense I feel like a healer as well. Art making is a form of healing—it's processing what can't be spoken into language that can be understood en masse.

How has your family/community responded to your path?

It took them a long time to come around, but I was pretty adamant about what I needed to do with my life. I've always had a vision of wanting to make the world better; writing is a way of accessing this for me.

What are some of the challenges you face being a creative in NYC?

Class. NYC is a hard city, and it's not really built for people that aren't inherently wealthy. I have many privileges, but familial wealth or stability is not one of them. And so I've sometimes found it really hard to thrive, especially as an artist, and also as someone that likes nice things. Not enough people talk about the cost of living in a city like NYC. That's something that's been apparent to me ever since I moved here more than a decade ago... I spent a few years in between in Montreal, which is known for being super affordable, almost like a Berlin, but in North America. Moving back to NYC in 2017 really shocked me because at the time, even despite being in a relationship that gave me a lot of monetary stability, that money was ultimately not my own. After coming out of that relationship early last year, I spent a lot of time flailing and being broke... and now with a pandemic, damn. It's really, in my opinion, shown how class privilege functions and alienates anyone that isn't rich.

What are some aspects of the industry you would like to see evolve?

Honestly? Everything. If we're talking about art spaces, or the writing world, everything is built on nepotism and white supremacy. So those things are fundamentally things that need to change, but that means you have to overhaul everything.

A short introduction of your origin and ethnic/cultural background:

I am a mix, mostly Chinese and a little bit Polynesian. I was adopted from Hunan, China at the age of one and grew up in Massachusetts in a predominantly white community and in a reformed Jewish household. Both my sister and I had a bat mitzvahs and went to Hebrew school every week growing up. It was an unconventional upbringing, but it created who I am and how I see things.

What type of work do you do in the creative industry?

I work in design, mostly clothing, but I've branched out into accessories as well. I mainly create looks that are a mix of ready-to-wear and more runway/statement style pieces in both mens and womenswear. But I think clothes are fluid. If you can fit it, you can wear it. I also take part in supporting fellow Asian artists and female creatives. My friend Shea Stiebler and I graduated in 2019 together, and we are currently working on a project that touches on the aftermath of graduating with a creative degree and the depression/confusion that can come with it. Unfortunately, it is on hold due to the quarantine, but we will be back up and running soon!

How does your identity influence the type of work you do?

My identity shapes my work completely and helps me to explore it further. My earlier work was really about accepting and learning my roots, both in Asian and in European Jewish communities. Growing up was really confusing and frustrating, because I never really felt like I had a space I fit in. I was never REALLY Chinese and never REALLY Jewish, because both cultures had boxes I didn’t necessarily check. So from there I like to make my designs from memories, places, and emotions of the past and also how I feel now, with a much more secure and happy embracement. I strive for my concepts to be intimate to me, yet easily relatable.

How has your family/community responded to your path?

I have an incredibly supportive family, which has been both amazing and lucky. My parents told me and my sister that we were adopted from the moment we could talk. They helped guide us through the muddy and emotional challenges that came with it. My mom really loves how I finally am happy and proud to be Asian, because until I was around 16, I really struggled with and resented it. I never had a problem with being Jewish, it was just about being the only person of color at Hebrew school and my Jewish summer camp. She always hoped I would embrace my physical identity and capacity for beauty, and I have, both in myself and my work. I have channeled it into creating beautiful things.

What are some of the challenges you face being a creative in NYC?

I think for me, I find it’s really hard to be seen. Being seen in NYC is like looking for a piece of glass in a bowl of crushed ice. There are so many people who have the exact same dreams, similar appearance, and just as much passion as you that it is hard to get a chance. I’ve realized a large part of being a creative in a place as diverse as NYC is also being a social butterfly. Connections sometimes get you further than talent and passion here, and it can be unfair. But that just means working harder, putting yourself out there, and taking chances. Not being afraid to get a no, and not being afraid to go for a yes. Due to the huge competition here (especially with other Asian female designers, there are so many of us), I’ve learned to be cognizant and to try to be a more confident and spontaneous me.

What are some aspects of the industry you would like to see evolve?

I would love to see people following up. During school, one of the biggest pet peeves of mine and my friends was loose promises. So many people want to say they support new/young artists, but not that many follow through and reach out. If I met someone at an event or through another platform, and they had more contacts/experience than me, they usually do take a peek at my work and offer their help and a chance to link up sometime. It was amazing to get positive and excited feedback on my work, but then after that, it was more or less just another Instagram follower and quietly liking each other's posts and watching stories. I’ve had some really lucky chances where that first contact did end up in an opportunity, but more people should have that, and it should happen more often. If you’re in a place to help someone else, do it. I’m still very new and young and looking for these chances. Even just sitting down for a coffee and some advice went a long way for me as a creative, and I know it could for others.

A short introduction of your origin and ethnic/cultural background:

My name is Jessica Wu, I'm 25 years old and currently based in New York City. I was born and raised in Orange County, in Southern California, but my parents are both immigrants from Taiwan. I moved to the city in 2012 to attend the Fashion Institute of Technology.

What type of work do you do in the creative industry?

I am the Press Director for the company I co-founded, Peter Do. We started the luxury womenswear brand with Peter and three other close friends two years ago, but we have all known each other for over seven years now. I am also a co-founder and buying director for my store ShopShop. In late 2019, I was given the opportunity from a client to ideate an online store entirely from scratch. My team and I launched an online concept home goods store focused on supporting and highlighting local New York artisans and designers. We are an entirely green business and operate on a sustainable model, using entirely recycled, recyclable, and biodegradable packaging and absolutely no plastic and buying small scale, committing to limited quantities.

In 2018, I started Period Space, a resource for menstrual and reproductive health and a platform for people to openly discuss and destigmatize the conversation around periods. After years of dealing with irregular bleeding and extremely long periods, I realized that the loneliness and shame I felt wasn't unique to myself. The platform is a safe space that encourages menstruators to feel at ease with their own cycles, practice body literacy, and feel comfortable with sharing their experiences. In my free time, I am a freelance model and work primarily with beauty clients and on commercial projects. I would love to explore doing more editorial modeling as the form of expression through styling, beauty, hair, and creative direction is usually more adventurous and interesting.

How does your identity influence the type of work you do?

As a Taiwanese American who grew up in a predominantly white neighborhood for most of my life, I often felt a sense of otherness, coupled with a longing for acceptance. I thought that blending into the background was easier than being singled out for my appearance and my heritage. My initial encounter with the notion of "fashion" in middle school entirely changed my idea about how I could be perceived—that I might be able to stand out for reasons other than my "Asian-ness" was groundbreaking.

The five founding members of Peter Do are all Asian American. Our tight knit relationship is reflective of the importance of the family unit across many Asian cultures. Being able to represent fellow Asian Americans in media is something that I never imagined possible. Over the years, I've had younger Asian girls and women send me uplifting messages about how they personally felt seen after seeing me on a billboard or an online ad. It's been humbling to have the opportunities to be able to be a face for those who feel underrepresented or unrepresented in the media landscape. I hope to continue to receiving opportunities that account for not only my heritage, but my body of work and what I represent as a creative.

We just can't let diversity be a buzzword or art direction requirement anymore.

How has your family/community responded to your path?

My family has always been supportive of my creative endeavors, albeit with a touch of concern and skepticism. I try to put myself into their shoes when I feel misunderstood or not heard, and in almost every situation, I realize that as much as my career and endeavors are new to me, they are things that my parents have never come across in their own lives or among their peers. Their concern stems from unfamiliarity with the field and the reasonable worry for my financial wellbeing in a city like New York. I was immensely lucky to have them support me throughout college and help with rent for 2 years after graduation while I was struggling with freelance styling and production jobs.

Being able to be pursue fashion in New York is an absolutely huge privilege. When I think about the generational difficulties that my family faced and had to endure to "succeed" when they came to America, I am reminded of all that has been afforded to me, beginning with the simple act of their acceptance with my career choice.

What are some of the challenges you face being a creative in NYC?

While I've become entirely accustomed to the fast-paced and competitive environment of NYC, dealing with the stress of balancing multiple pursuits is undoubtedly one of the biggest challenges I face. I have a strong work ethic and like to think that I have great time management, so I make sure that work is done within reason and I don't bite off more than I can chew. But, the deeply ambitious and perhaps overzealous me tests that theory quite often...

While I've been lucky to receive work through social media, I also believe that it's unfortunately an instrument that can encourage dangerous feelings and reinforce the habit of comparing yourself to others. Sometimes I feel instantly uninspired with certain pursuits, because it's hard to dismiss those small voices in the back of my head asking, "Why didn't they choose me?" or "How did they get that?" or "Does any of this matter?" In those moments of self doubt, it can be incredibly hard to step back and realize how much you've achieved. I'm still on a personal journey to diminish the idea of social media validation in my life, so that I can holistically evaluate myself and my career without those unnecessary pressures.

What are some aspects of the industry you would like to see evolve?

I am hoping, especially after the height of this pandemic subsides and especially due to the severe disparities it's revealed, that the fashion industry takes responsibility to address issues like corporate social responsibility, sustainability, ethical wages, and operational transparency. I'd like to see the biggest players implement these practices so that they can lay the groundwork for other companies of varying scale to have something to follow, and for the democratization of such practices to entail their financial accessibility at large.

A short introduction of your origin and ethnic/cultural background:

I’m half Thai. My mother grew up in Bangkok and came to the States as a teenager, and my father is American. I grew up in a multicultural household in the Midwest, and I came to New York shortly after university. I didn’t have the privilege of growing up in a highly diverse community. My mother's family actually opened the first Thai restaurant in my hometown in 1990 if that is any indication of the lack of diversity.

What type of work do you do in the creative industry?

Currently I’m making a living as a fashion stylist. In my personal projects, I’m focusing on sustainability and material value in response to fast fashion and over production.

How does your identity influence the type of work you do?

Like my identity, my artistic practice is neither black or white. I try not to define what I do in words as to not limit myself in modes of creation. Because of my multi-cultural experience, I can’t put myself into one box, and I don’t want to confine my work in that way either. Experimentation, curiosity, and alternative approaches are important to me; I constantly want to learn new things and apply all of this to what I do.

How has your family/community responded to your path?

I am extremely lucky that my family has been so supportive of my pursuit. My father is an architect, and I grew up in a beautiful home, valuing material, design, and sustainability. I think most Asian American households put an intense amount of pressure on their children to be successful. My mother was quite strict when I was younger, and we’ve come to understand each other more over the years, working to realistically uphold traditional Asian values in our untraditional experience.

What are some of the challenges you face being a creative in NYC?

It’s very difficult to be creative in NYC and make a decent living. It’s hard to find balance and continuous tenacity in a highly exploitive system. Many young creatives have expectations on monetary success and visibility. Because we often communicate and share work through various digital platforms, it puts a lot of pressure on the rate that we are producing. I think these pressures disrupt the standard and novelty of the work.

What are some aspects of the industry you would like to see evolve?

I hope creatives can have a larger voice in the industry and dismantle the bureaucracy. I hope collectively we can hold billion dollar corporations accountable for their oppression of communities, cultures, and the environment. As makers and producers, it’s necessary we educate ourselves on supply chains of the industries we’re working in. Especially in fashion. We’re not immune to the destruction and mistreatment that our industries inflict.

A short introduction of your origin and ethnic/cultural background:

I’m half Malaysian and Chinese. My mother’s family is Malaysian, and her grandfather emigrated to China to do business, which eventually was seized during the Cultural Revolution. My parents grew up in rural Guangdong, China. We grew up speaking Hakka (a language I can only speak to Aunties and Grandmas with), and my parents owned two herbal shops in Chinatown; one was on East Broadway, the other on Hester Street. I snuck ginseng root into my snack time and pinched dried mushrooms when I was a kid.

What type of work do you do in the creative industry?

I’m currently marketing in the beauty industry, though I do have my esthetician’s license. Where I am in particular is natural skincare, which emphasizes using plant-based ingredients. Skincare was always a cornerstone in my teenage years, my mom whipping up pearl powder egg white masks to ease my cystic acne.

How does your identity influence the type of work you do?

You take your roots with you. The joy that my parents relish in when they offer herbal remedies is how I feel when I touch skin. My job focuses on the external, though my upbringing was focused on internal

blockages. Nowadays, you see the holistic beauty niche move into Traditional Chinese Medicine, which has never been unique to my family, but it has become sensationalized and even gimmicky. What was

regarded as superstitious and quack magic is now what many non-Asian Americans turn to.

How has your family/community responded to your path?

Beauty wasn’t the path that I chose when I was in college. I was an English Literature major, though I didn’t start to engage with my Asian-American roots until after school. My education was, quite literally, black and white. All my courses were focused on European literature, which was required, and the other half was African American studies. I was able to take maybe two Asian American courses, and they

weren’t even in my major. Where I am now was serendipitous. I worked at a spa during college, enjoyed the facials, but the estheticians I worked with inspired me. They were passionate about healing, nurturing and finding solutions.

What are some of the challenges you face being a creative in NYC?

Balance. It’s hard to turn off when you’re mentally bookmarking “content." What we see on feeds and social are highlight reels, and it’s hard to not feel FOMO. On the other end, it’s just regular people like you

and me creating that sensation.

What are some aspects of the industry you would like to see evolve?

I’d like to see more pro-aging in the beauty industry. We see a lot of anti-aging… fight wrinkles, banish fine lines. It’s a privilege to become wiser, gain more experience, and reinvent yourself 20 times over.

A short introduction of your origin and ethnic/cultural background:

I’m Korean. My parents were born in South Korea and moved to California, which is where I was born. I grew up in the Bay Area and am from Palo Alto. As a child, I went to Korean school every Saturday. I mostly remember practicing to write journal entries in Korean and my favorite: learning traditional folk dances using feathered fans and long pieces of fabric.

What type of work do you do in the creative industry?

For industry jobs, I've done mostly artist assisting and design assisting jobs, but currently I work at the Simone Rocha store. It’s a change of pace, very calm and quiet. There’s a Louise Bourgeois sculpture hanging from the ceiling next to another one of her pieces, "Lullaby." There’s a Rauschenberg greeting you at the door along with a sculpture made by bees. In my free time, I like to craft, paint, sew, make food sculptures or anything that my calls to me.

How does your identity influence the type of work you do?

My identity has everything to do with the type of work I do. My experience of growing up bilingual has informed so much of who I am, visually and mentally. It allows me to think in two different languages and have dual base reference points for everything. There are words and expressions for things in Korean that simply aren't translatable to English, and that space of void really inspires me.

How has your family/community responded to your path?

My family has always supported me learning the arts and has always provided avenues for that as a child, whether that be through musical lessons or art classes. I think they may have viewed it more as an extracurricular rather than a career initially. However, they continue to be supportive of it even though they may not always understand it.

What are some of the challenges you face being a creative in NYC?

I think the biggest challenge of being a creative in NYC is finding a day job that doesn't deplete you of all your energy from pursuing or expressing your own creative desires.

What are some aspects of the industry you would like to see evolve?

An aspect of the industry I'd like to see progress past is this sort of expectation, especially in art and fashion, that people should always work above and beyond for little or no pay. I think it’s important for the narrative around that type of expectation, culture and glorification around overworking yourself under the guise of it being for experience be changed to one of empowerment, for people to know their value and what they in turn deserve for it.

A short introduction of your origin and ethnic/cultural background:

I am part of the Bangladeshi diaspora, rich with a textured history and culture. I also identify as a Sufi Muslim which drives my tenderness and creative Spirit.

What type of work do you do in the creative industry?

I am a writer foremost, but I also understand writing as an immersive experience interwoven with various modes of work including research, travel, and activism.

How does your identity influence the type of work you do?

My layered identity cultivates an intersectional lens to unlearn, imagine, and think with. As a Muslim Bangladeshi American woman, when I write, I first try to find my position in the space. How am I taking up space? Reclaiming space? Am I appropriating any spaces? What identities do I carry that will shape this story? Which voices need to be centered? How will I uplift transnational feminism? Confront structural oppression?

How has your family/community responded to your path?

After some profound self-advocacy, my family for the most part has been supportive of me. Yet, there are days I feel dejected by the uncertainty of being an artist in a world where art is often devalued. My chosen family lovingly supports my reflection process and holds my hands through the journey of Self.

What are some of the challenges you face being a creative in NYC?

So often, Asian American creatives are expected to create art about their descent, while white people are allowed to be multidimensional and exist outside of race. The saliency of Asian-ness is a facet of whiteness, where artists are hyper-racialized, fetishized, othered, and exploited. The rhetoric that reduces the Asian identity as monolithic is disservicing the labor that these creatives are exhibiting. My fear is that our institutions may make space for our work temporarily to appease their quota or pseudo morals, but are not consistently thinking of ways to push for systemic changes.

What are some aspects of the industry you would like to see evolve?

I celebrate the nuances of my art as a multifaceted individual, interwoven with the Asian identity. While the work and portraits of creatives are inherently political, we must look beyond spectacle in order to dismantle stereotypes and challenge the white gaze. New York City has anchored me in many ways by inspiring me with abundant artist communities aiding one another. I hope to see more community empowerment, vulnerability, and growth. I also firmly believe in the power of looking inwards. While I am able to critique aspects of the industry, I also have to challenge myself to envision a new normal and work in solidarity with powerful marginalized identities.

A short introduction of your origin and ethnic/cultural background:

I was born in Canada and grew up in Hong Kong. I went to a local school in HK up until college, when I moved to New York.

What type of work do you do in the creative industry?

My career started out with the goals of being a more traditional illustrator, since that’s what I went to school for. But recently, I’ve decided to shed the label of an “Illustrator” — I think I’ve grown more into just a digital artist, as my working medium continues to expand.

How does your identity influence the type of work you do?

I’m very grateful have spent my formative years in a city like Hong Kong. Visually speaking, the city is so abundant with a rich history of art and subcultures. Even just thinking about simple things—like the city’s urban planning, architecture, food menus—give me a wide mental visual archive to work from. Lately, I’m also realizing just how much Cantonese humor indirectly informs my work. It’s intentionally simple and random.. like the pointlessness is the punchline, paired with very nuanced understanding of the culture. Shaolin Soccer is probably the most mainstream example in the US. Looking back, I realize I often find the “spark" in my work by approaching a topic with a similar sense of absurdity and sneaking in lighthearted personal references occasionally. Sometimes, all it takes is the most elementary surprises to keep people interested!

How has your family/community responded to your path?

Fortunately, both my parents are more on the artistic side, so my immediate family is mostly understanding of my path. As for my extended communities back home, they are still very confused about my career choice, given that I don’t have a straightforward answer when they ask, “So what exactly are you doing in New York”?

What are some of the challenges you face being a creative in NYC?

Not sure if this is specific to NYC, but finding a community was a huge challenge for me for the longest time. It’s lonely being an artist who mostly works alone to begin with. I’m very blessed to have met fellow creatives that I adore and respect a lot. It’s definitely still a slow ongoing process. Perhaps it’s also because there’s just so many creative people in the city—it’s extra precious when you meet people you have a solid mutual understanding with.

What are some aspects of the industry you would like to see evolve?

This is a far more complex topic than I can get into right now, but we should no longer gloss over how the ability to be creative is a huge luxury and privilege in and of itself. It shouldn’t be this way to begin with—cultures like unpaid internships, and lack of resources for young people in the arts further strip away opportunities for individuals who are equally as talented and hardworking than those without the financial and social backings. Overall, I want to see young/vulnerable creatives have their time and talent compensated differently!

A short introduction of your origin and ethnic/cultural background:

I was born in Seoul with dual citizenship during my parents’ Christmas vacation who resided in Texas, where I was raised. Did you catch that? Me neither.

What type of work do you do in the creative industry?

I make clothes, draw, and write. My main trade is fashion, because there, my mediums and musings can fuse together. Professionally, I teach two fashion classes at an arts school in Harlem and work as a pattern maker.

How does your identity influence the type of work you do?

Identity, connection, diaspora, language, gender norms, and utopia are things I always think about. My work is largely inspired by the deconstruction of my bicultural conservative upbringing and my efforts to imagine an expansive future.

How has your family/community responded to your path?

My mother worked tirelessly to provide for me and my brother after our dad passed. She has always supported our endeavors, but my work causes friction, because it challenges the pillars my family stands on: religion and tradition. My communities from RISD and New York remind me that I'm not alone. Weirdo visionaries exist, and we'll see change through.

What are some of the challenges you face being a creative in NYC?

Juggling compromise and time.

What are some aspects of the industry you would like to see evolve?

Fair pay and originality would be great places to start.

The Coronavirus epidemic isn’t the first storm Forgtmenot has weathered. Just three months after its opening in 2012, it was christened by Hurricane Sandy, and despite much of lower Manhattan being flooded, Forgtmenot stayed open. “It was kind of our birth through Sandy,” Tighe says. The bar made it through and even went on to expand in the coming years. It wasn’t apparent then, but the trial with Sandy would foreshadow the business’s resilience.

After Mayor De Blasio declared a city-wide lockdown, Forgtmenot tried to remain open doing deliveries and food-to-go, “but it really wasn't a viable option for us,” says Tighe. It didn’t bring in enough money. At their wits end, but unwilling to give up, the idea for the conversion came to Tighe while he and the owner, Paul Sierros, were sitting at the bar one dreary morning: “We were having a whisky, talking about what we could do, how can we stay open, how can we survive, and we thought, ‘You know, we have the avenues, we have the supply chains for products, why not switch around and do a super market?’" It took less than twenty-four hours to put the plan into action. Working non-stop through the night, Tighe unbolted the furniture from the bar’s floor, built plywood shelves to house the produce, and moved everything they didn’t need to storage, turning Forgtmenot into the FMN General Store.

Aside from the dark wooden bar off to the left of the entrance, the space looks like it could have always been an eccentric, trading post–themed bodega. The old country music that plays over the speakers is the kind that you'd find in a dusty, small town saloon whose patrons order double shots of whiskey. There are knick-knacks, trinkets, and mementos, which all provide scenic camouflage for the goods that are actually for sale: Woven blankets, espadrilles, and vinyl along with the usual perishables and nonperishables. Everything in the store is crammed up next to and stacked on top of everything else: The record crate is next to the Ritz crackers; the flour can be found beside an oil painting of a Doberman. Clutter is an aesthetic here, and it gives one the urge to browse. (Which is safeguarded by a hand-sanitizer station right at the entrance.)

“It was crazy he got it all done in a night,” says Mark Nardelli, friend of the Forgtmenot crew and founder of NYC-based skateboard and apparel brand, 5boro. Nardelli is one of several people who are spread out on the quarter-block space outside of Forgtmenot, drinking, skating, and arguing about soccer. The Forgtmenot community is close-knit, which is why it was particularly devastating that the store had to downsize. “We went from having about seventy employees in total to about ten or fifteen,” Tighe says. “We've had to lay off a lot of people that we've known for years. We're hoping obviously that we can take them back, but it's hard. It's family. We all live in this neighborhood; I've lived in this neighborhood for about twelve years. It's very much a community vibe here.” And Forgtmenot, for some, is very much a home.

“That small stretch of Division Street changed my mother fucking life,” says visual artist and Forgtmenot partner, Adam Lucas. Though he’s established in the downtown art scene now, Lucas was at one point in time slinging chicken and pork sticks from a food truck owned by Abby and Paul Sierros—and loving it. “They were my Big Apple family,” Lucas says, “and when they approached me to partner with them on a small brick and mortar in Chinatown, I agreed (despite being damn near dead broke).”

It seems comaraderie was foundational to Forgtmenot’s beginning. As Lucas recalls with nostalgia, “We built the place ourselves and couldn't afford to hire any employees for months (actually taking turns sleeping in my car parked out front). But damn it all if it wasn't exciting as hell. Food and drinks during the day, art and more drinks at night. Then we'd wake up before sunrise to surf 90th street, followed by a quick drive back to the city to open the restaurant.”

Now, in the face of crisis, it’s apparent that this bond which the founding Forgtmenot members cultivated is being reflected in its patrons. Many of Forgtmenot the Bar’s regulars have become FGM the General Store’s regulars. During our short, ten-minute interview, three different people popped their heads into the store to say hello to Tighe, promising they’d be back after their walks. “For me,” Tighe says, “the Lower East Side and Chinatown are some of the last neighborhoods in the city that still retains their authenticity. They’re still community-oriented. We're indebted to the community here—first of all for supporting us along these eight years, but also for supporting us through this too. Many small businesses, not just bars, aren't going to reopen after this. So our mission is just to stay alive.”

Thanks to Tighe’s resourcefulness, right now the business is operational; the idea of Forgtmenot, still very much alive. Those who used to frequent the place for a drink still can; they’re just served from a cooler on the sidewalk. “I think of us as a small-town trading post,” Tighe says, “where people can stop in for a minute, have a quick chat, and just pop on with their roadie drinks to go,” a method of operation that retains FGM’s close-knit charm. “Are we making anywhere near as much revenue as we would as a bar? Absolutely not,” Tighe says. “But it's keeping our doors open.” And it’s giving the community a chance to support a business it loves.

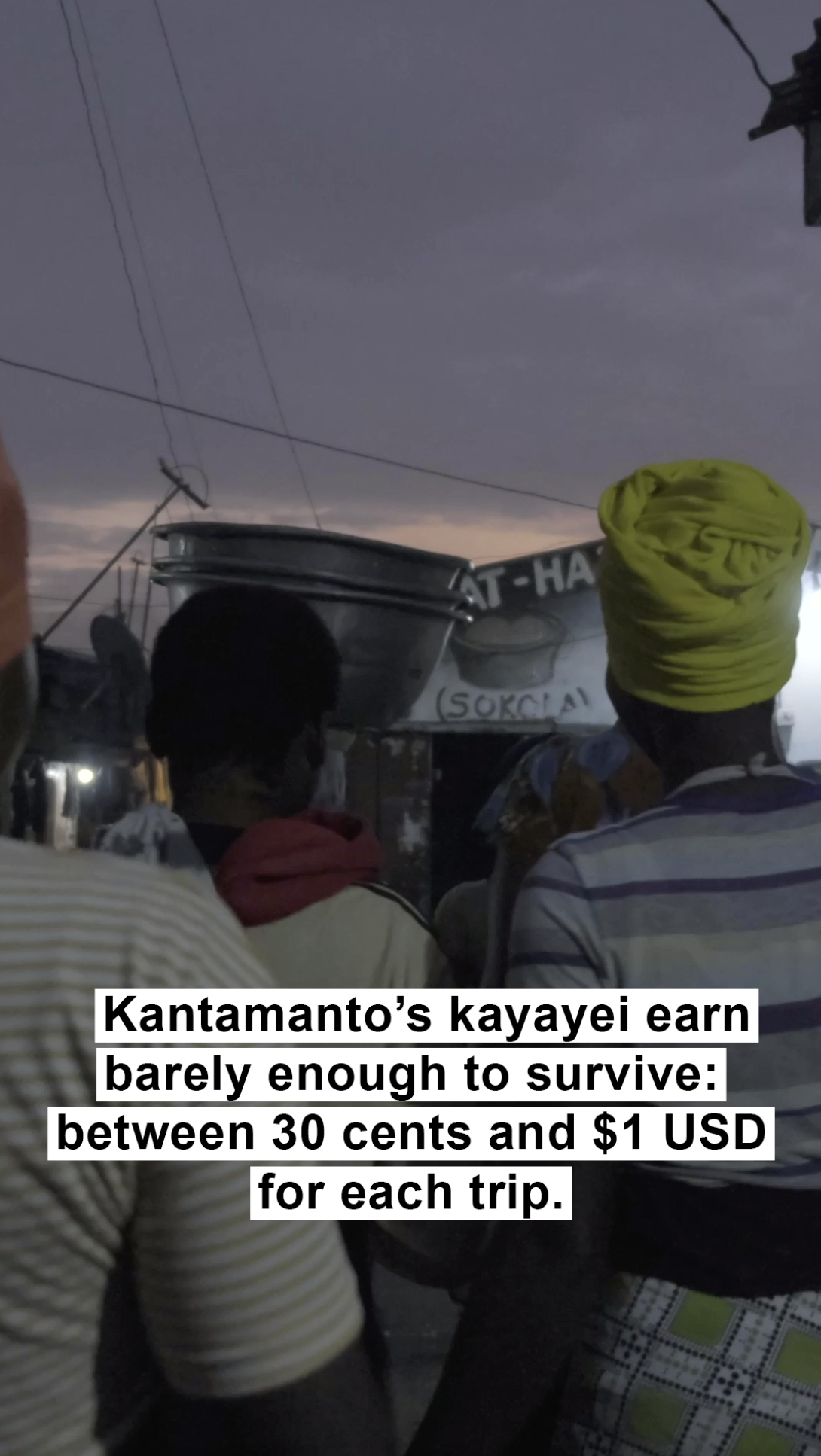

Below are stills from the film to give you a glance into the world of the women fed by an office bag purchase.