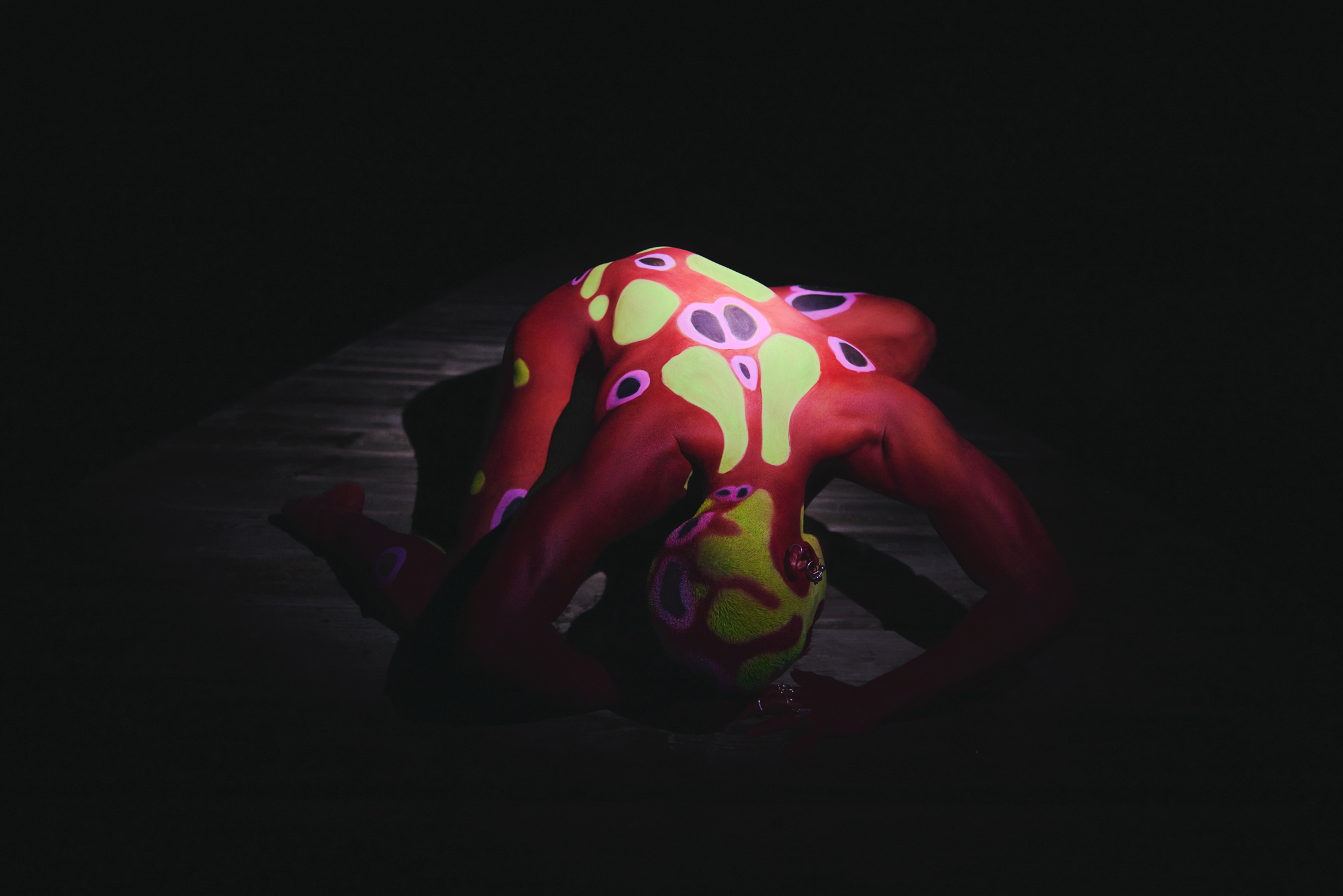

A horizon amidst the chaos.

Yes. Is it progress or is it just curiosity? I don’t know. Theres always a question of: I wonder if that is possible? From this I might say could there be a monochrome? Is there a way in which the uniform color is an opening shot towards creating a monochrome? And that comes from thinking what is the worst thing you could probably do, what is the most dumb and dead thing you could do. Often times I think those are what gives the most fruitful exchanges, because one, monochromes aren’t British really, so that’s already gonna be odd if I do it. And I suppose this is like that too. In this country, many students have painted like that, much more than in Britain I’d say. But having crept toward it through something else, it’s like putting a different flavor in a meal, it has this sort of conundrum to the combination of things it’s trying to do. In some ways it’s like European figuration, Classical figuration, but then it’s sort of also woven into Joan Mitchell via Manet. In a way the game of painting, with the volume of history, is that there’s always a possibility of bringing your enthusiasms together into a surprising combination that allows you to see something new, which is similar to what I said at the start about seeing the gaps. And its abstraction as a language, reducing and subtracting, rather than the art historical idea of progressing from images. But I think progress doesn’t really exist, certainly in terms of painting. I think it’s for all times.

It’s interesting to hear you talk about your works in terms of a genealogy of painting up until this point. To me, trying to digest the breadth of that awe-inspiring history reminds me of the Loren Eiseley essay which inspired your show, in which he chronicles the evolution from mythic notions to the scientific method as two respective means which help us digest and comprehend the awe and phenomena in our world. How did Eiseley’s emphasis on the evolution from mythic to scientific schools of thought — and the essay more generally — inform your work for the show?

I started by liking the title, because it begins with the word “How.” Again it’s about the questions, I could’ve called this show “How," or “How do you make a painting?” Once I dove into the essay, when he was talking about the trend from myth to science, I felt like it mirrored what I was doing. Science is our way of making things more certain around us, and concrete and trade-able as an idea. It’ll say this is why this happens and we all socially understand how science has contributed to our understanding of where we are. But I think that with painting you sort of begin with that, you don’t work towards it, but you begin with that, and it evolves into something that is not made sensible through science — it becomes a private form of mythic thought, in which your reasons why things happen are fictional, and your combination of things can be mythic in terms of hybridized forms, things through time, things influenced by different times and different eras of your own life but also in art history and earth history. So I just liked the idea of working back towards something that was more mythic in the sense that it has in the essay. So one of the things I liked about making these is that they combine things from my own experience that don’t really combine in any other way, a bit like you’re in a life or a thought, a place of flux and incongruent things which only exist for you, until you speak and put them into some sort of order, and the works are the speech. But because it isn’t speech it allows you to join them up how you want, and I think that joining them up into something convincing is like a myth because you want there to be an awe to that. The way I would understand that is thinking about the sublime or nature, where you’re kind of inundated with the volume of it, whether you’re talking about Burke’s sublime or Kant, it’s a complicated and large issue, but what I do know about it is that in a way it’s about the parameters of how you understand something being too big, so you can actually digest and make sensible the thing around you, so there’s a sort of terror involved as well as fascination. And I would say that that’s familiar in this. I’ve sort of set myself into that position because I don’t really rehearse them in any other way. I don’t go into photoshop and cut bits up and put them together, I don’t do collages or drawings. I do little fiddling about things, but when it comes to doing that I’ll look at a bit and take another bit, like listening to music, once it’s come and gone I don’t look at it again, it goes in or it doesn’t, it’s like a moving thing that keeps on going.

I suppose that it’s all about definition, like how am I using the word myth, well I think it would be mystery. And I think that it works when there is some emphatic and convincing way of it being delivered. And I think what I try to do is paint it as though it is an image, with the conviction of having looked at something, but it’s actually based upon having thought something.