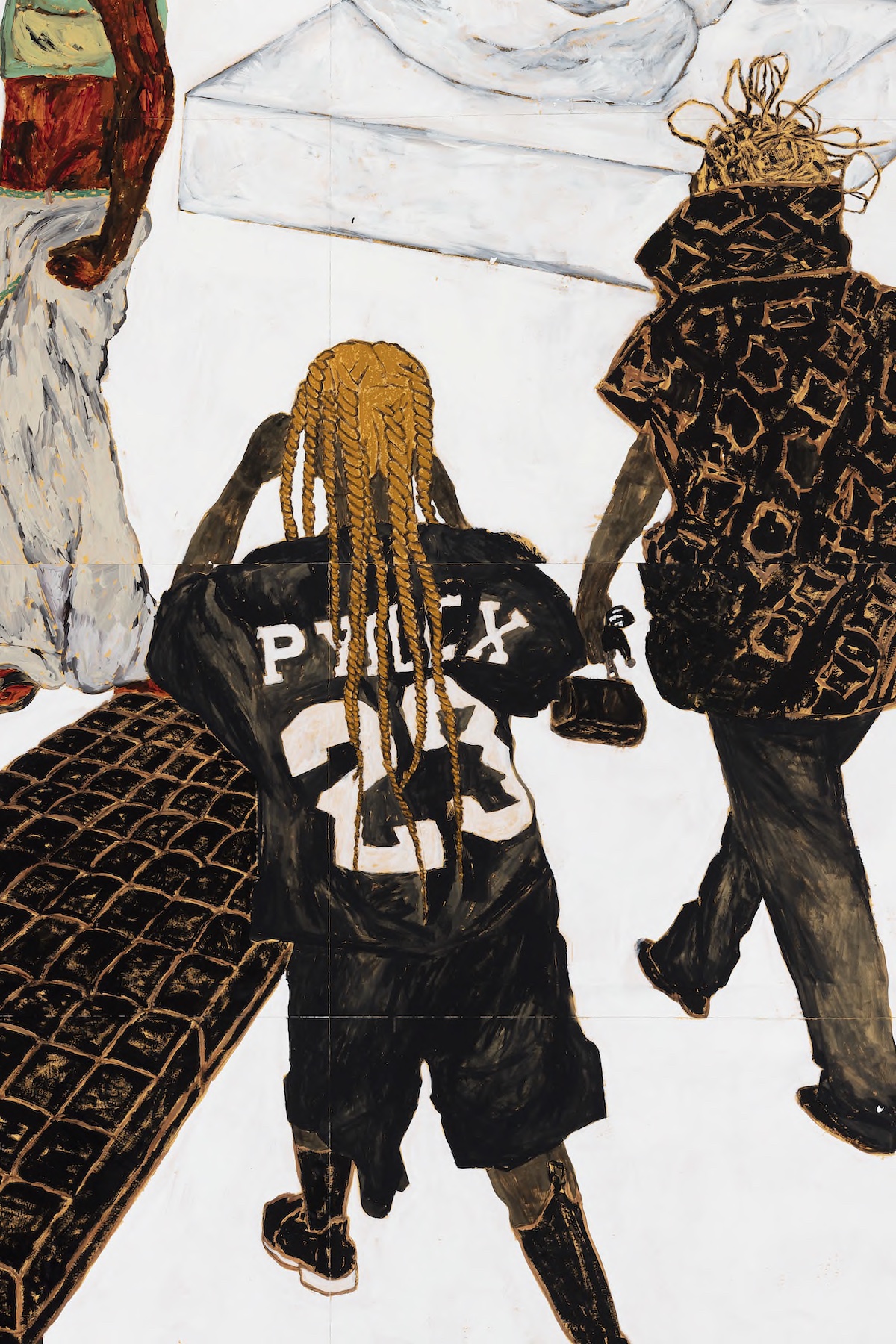

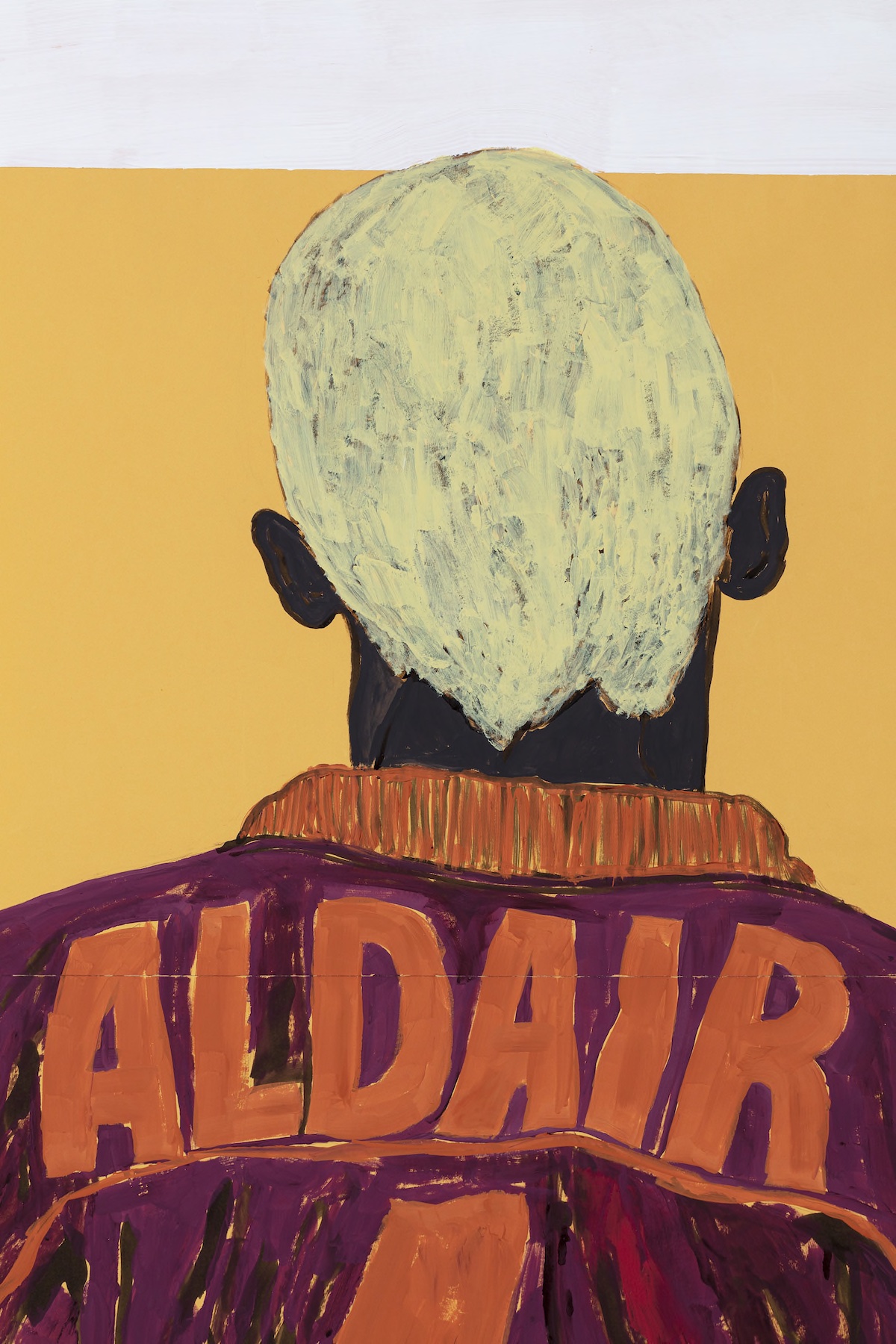

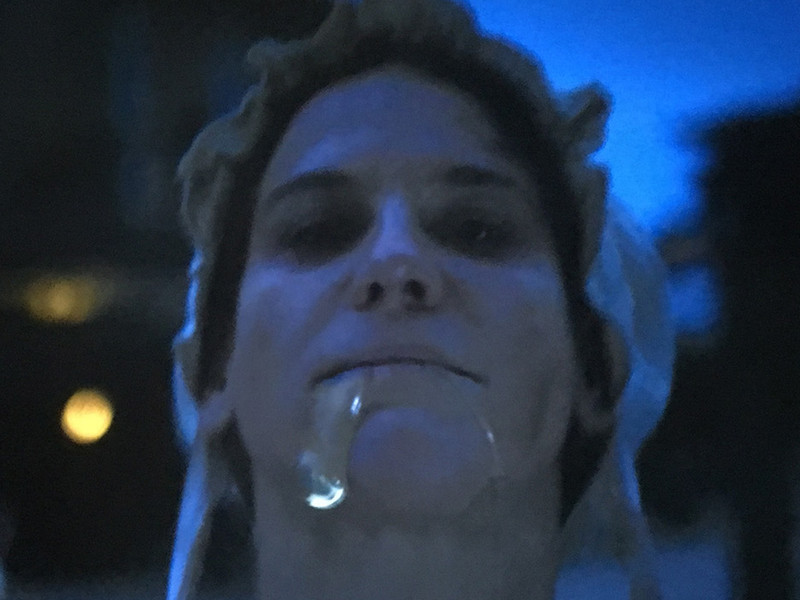

It is highly apparent that you make an effort to remain grounded in, legible, and accessible to your communities at home in Rocinha and across Brazil. In addition, you are very intentional in finding ways to activate your work with physical demonstrations such as "Rolezinho" or "Descoloração global." I love how these elements of performance art/art activism exist as a conceptual extension of your paintings, the Rolezinho mirroring your New Power paintings that place black bodies into elite art institutions, and your Descoloração performance piece complimenting the figures in your artworks which have bleached blonde hair and pay homage to the popularity of that hairstyle in Rocinha culture. Please tell me about your process of adding these physical demonstrations into your practice, and how these demonstrations are an outgrowth of what I perceive to be an interest of yours in art activism.

MA— I am not an activist, but an artist.

Activism is what’s expected from a black person, it’s a stereotypical label that applies in the case of a strong black person, who thinks, makes demands, questions, competes, is strategic, and knows how to position him or herself. I think that all these attributes are also part of the makeup of a good artist, so it is important that I have them. Being an artist is a luxury, it is superfluous, and from a social point of view, when successful, it is a divinity; it is the light, the profession that confers a status of the highest prestige. That's why it's so hard for me to remain only in this place of an artist, which is not customary. The word “activist” helps to better define and encompass my place as a black person, so it is necessary to complement my status as an artist as a means of putting my mind at ease, an aid for me to come to grips with my exclusive position. All of this sounds to me like people saying: "Why is that black guy just idle, doing these meaningless things? That's a thing for white people, that black guy should be struggling to lift his people out of the misery that we have set up for them forever." In other words, being black is to be miserable when one is down, and then, once one rises up, one has to continue the struggle, maintain the "activism." There are only these two places for people like me, misery or struggle, never just idleness, plenty of leisure for the thoughtful spirit.

I must reject this label of artistic activism because I want to fully enjoy all the benefits of being an artist in society. Being an artist is synonymous with freedom, craziness, senselessness, and just idleness. These are the attributes I want for myself. I don't want commitment. I want the idleness. I want to not have to do anything. I want the lack of any practical purpose, which is the most valuable thing that art has to offer, especially in a world where we must have a “why” to everything, where everything has to work; I want to have no usefulness. I don't want to be an example, I don't want to fight for everything, including for my own survival. I want to be able to contradict myself, I want to be negligent and still be forgiven like white people are.

Don’t demand activism from me, I am an artist. Art is unknown, questioning, with no commitment to objectivity, it is not exact. And yet it is a behavior, a posture and the artist’s place is on the fence, maintaining a state of permanent questioning.

What I'm saying here is related to the previous answer about the Garden of Eden that I painted in the work Me dê a maçã [Give Me the Apple]. I want to eat the forbidden fruit. Let me sin. Sin is the food of life.

As an artist, you are not one to shy away from institutional critique. You are acutely aware of the history of exclusion and the hypocritical nature of art institutions that use the work of Black artists as a band-aid to histories of oppression and discrimination, in some cases enacted by said institutions. Recently you had a dispute with the Inhotim Institute where you asked for one of your works to be removed from a group show of 33 artists that was created to be shown in alignment with the “Dia da Consciência Negra," declared a National Holiday in Brazil in 2017. Why is it vital that you use your platform to speak truth to power, and how do moments like these help to create pathways to a more inclusive and equitable art world? How do you walk the line between honoring your belief system, and navigating an art world where power is skewed toward the institutions, and speaking up too much can get you labeled as an angry "black who attacks"?

MA— We could say that this stance of mine is only possible as my work’s growing in potential and I become each day more relevant in the scene. But since the beginning, I have been laying claim to my career steps and negotiating them with autonomy, and I've already had several confrontations with art agents and institutions because of it. Of course, at the beginning no one listens to you, and it makes sense that they wouldn't, when you haven't proven yourself yet. In other words, in the games of power, vanity and money that sustain the art circuit, you only gain a voice once you have generated credit in that system. And that's what I have been doing – just look at the amount of credit I have garnered for my name and work in recent years. Why are they still unable to accept my size and relevance? There are no precedents for my case. If you analyze my accomplishments and résumé, you won't find parallels, even among white artists, in terms of my performance in the professional art circuit, in such a short span of time. And my work’s excellency, my ethics, and my stance as a professional artist are the basis for making my objections.