Artist Dylan Rose Rheingold experienced the palpable pressures of girlhood in her younger years, often feeling like she was shrinking or altering herself to fit into a mold that was created for an unattainable ideal. Through learning to accept the differences that characterize her, Rose creates space for other women to accept the pieces of themselves that they did not have the strength to before.

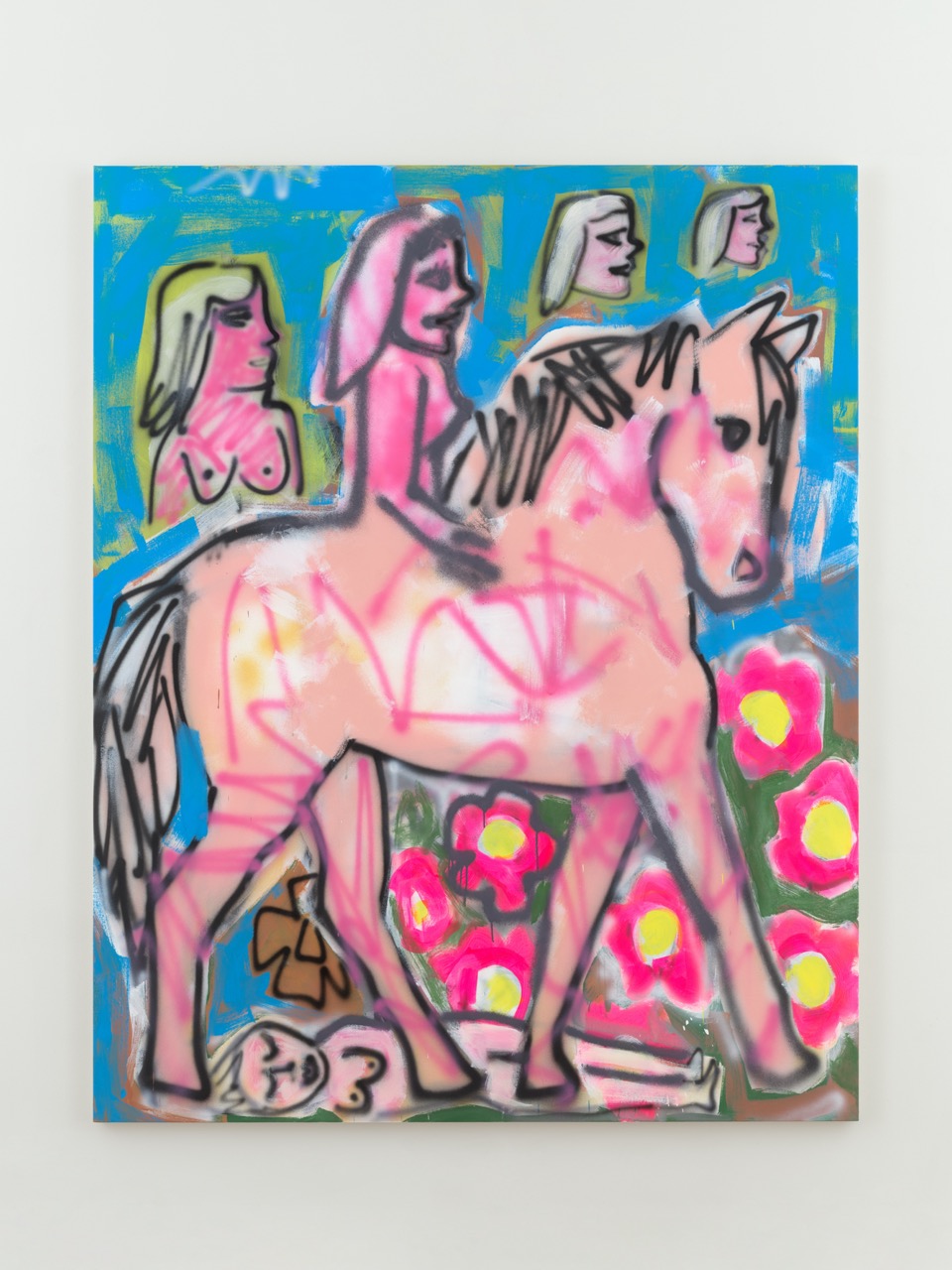

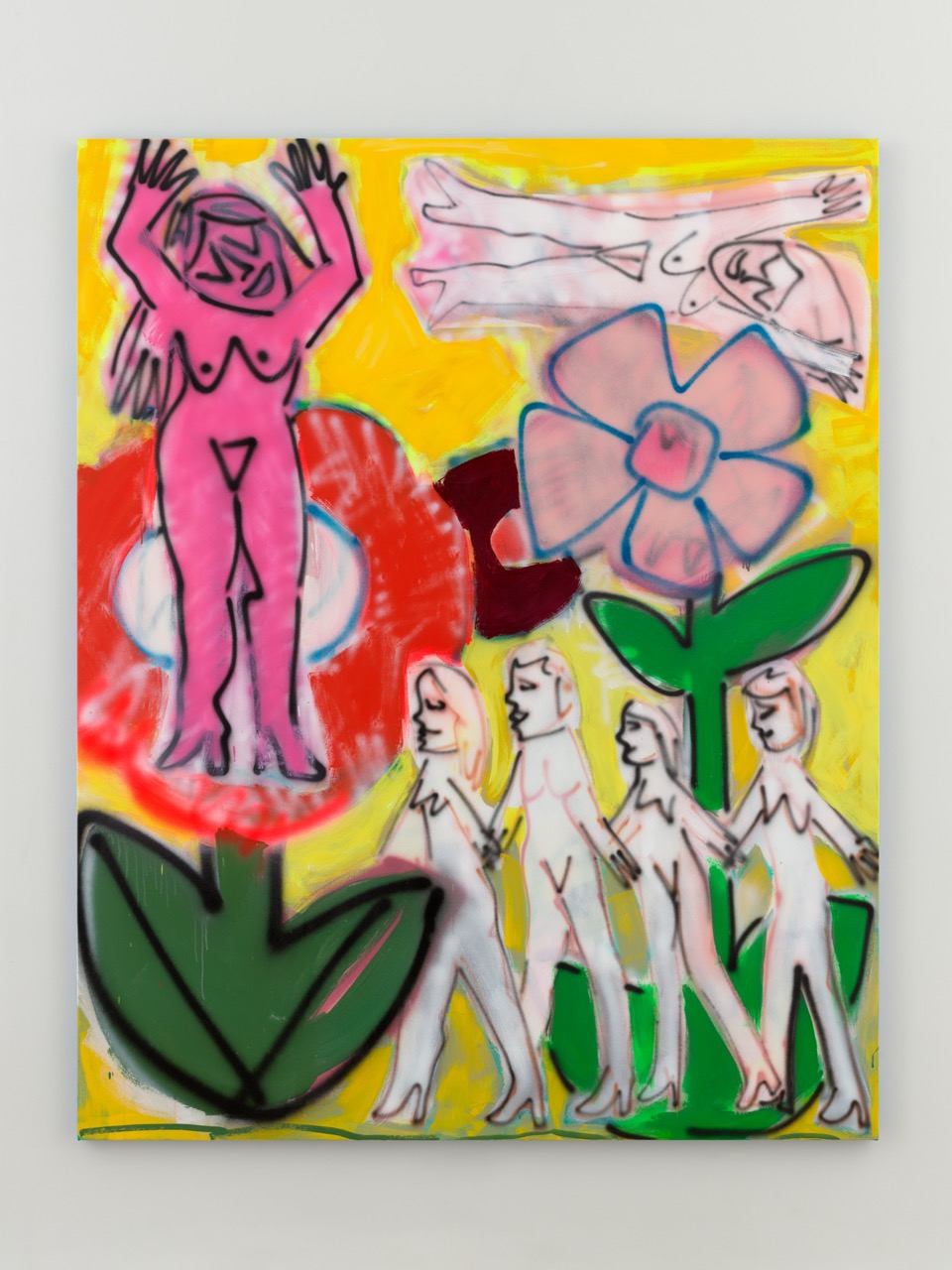

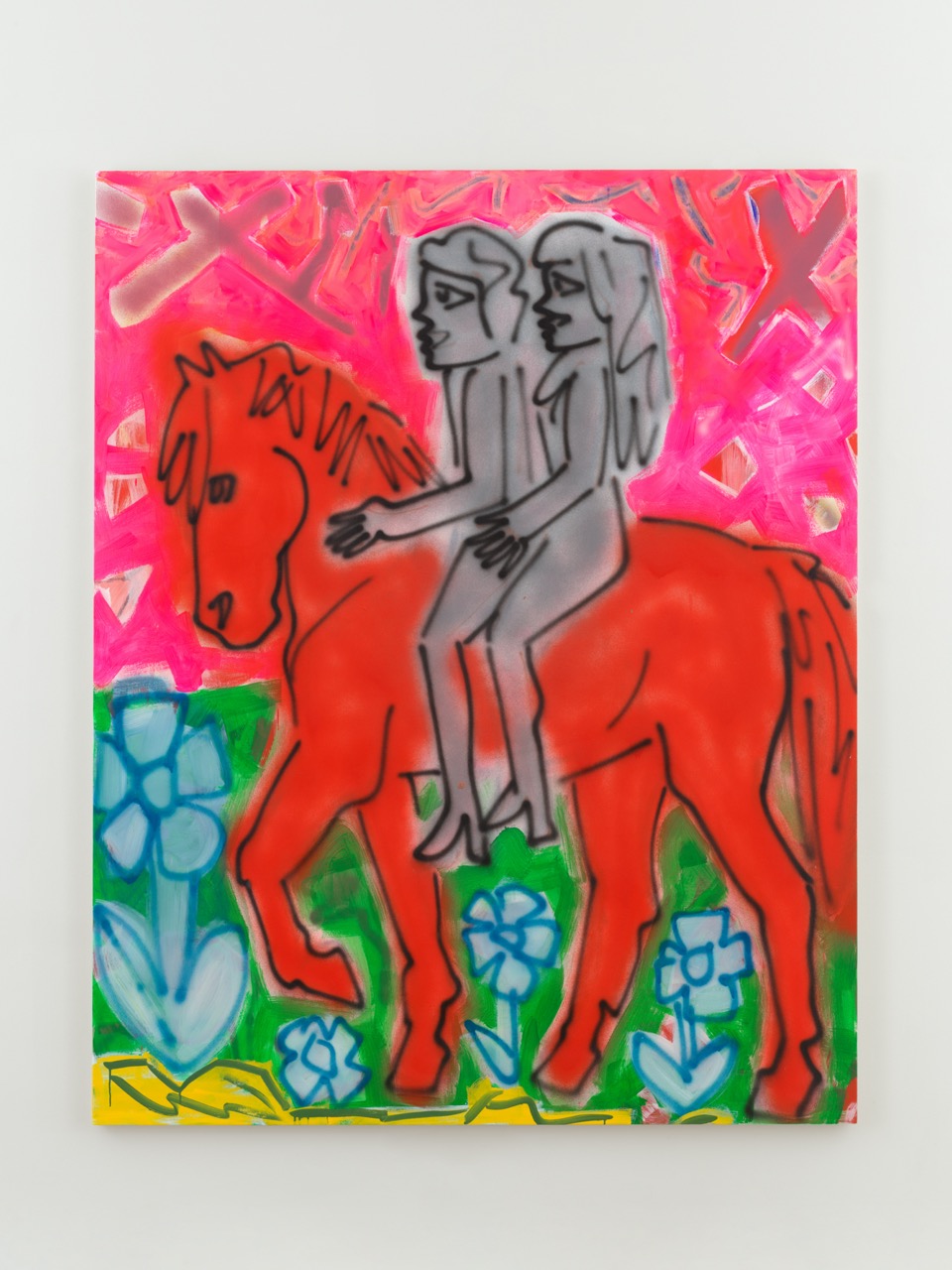

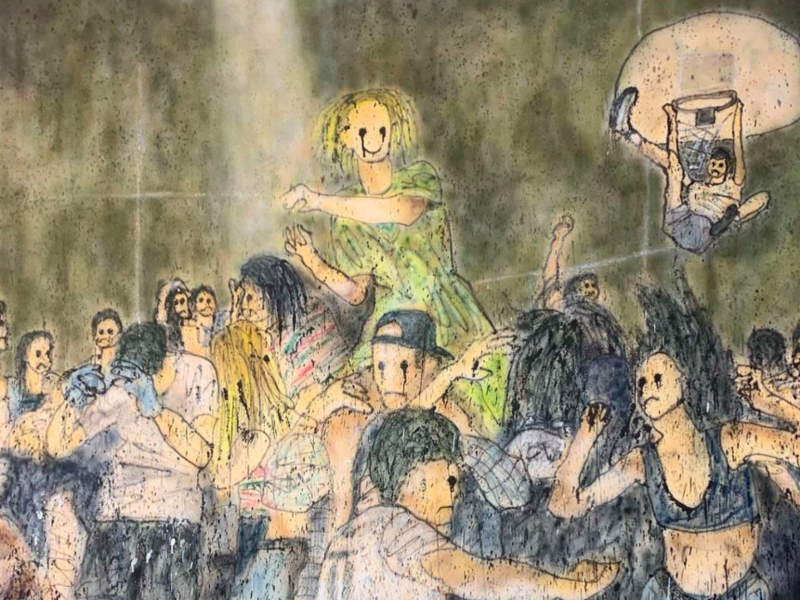

Rheingold’s latest exhibition, Best in Show, now open at M+B, explores the journey of girlhood. Through a series of mixed-media paintings, she conjures nostalgia as she draws from early memories, channeling the notion of competition as she recalls her high school’s color war competitions.

You grew up in a suburb outside of NYC — a child to a Japanese mother and a Jewish-American father. How have you learned to weaponize or reclaim this idea of “otherness” that often arises during adolescence?

Within my adolescence, that idea of 'otherness' wasn't something that I ever pushed away, but it was just something that I felt and I didn't really know how to express. But being submersed in a community that was so insular, there was so much of the same. And if you didn't fit into that box, you stood out. I kind of felt like I was almost floating; not really knowing where I should be. I don't think I ever had a point where I was ashamed or blocking out my origins, but I definitely wasn't as inspired or curious to explore my roots.

You allude to the many preconceived notions embedded within our minds as we mature. Social hierarchies are inevitable, as they allow us to categorize and classify people and their actions. As you’ve matured yourself, how have you unlearned these standards?

I think it's from honestly just putting yourself in a different environment. In college, I made so many friends from different walks of life and I became interested in their history. It made me take a step back and think, 'Whoa, why haven't I really taken the time to think about my own?' I started building this family archive of photos from both my parents’ sides. And I was making a bunch of collages at the time. I was really interested in Rauschenberg's collages — I'm a big fan of him. So I started making these collages and I didn't really have any intention of showing them. It was more just like an exercise for myself. But it really helped inform my voice and my thoughts, and I was able to create these obscure combinations and connections. I kept making these as I started grad school and started looking inward. I realized that what was so attractive about those images and pairing them side by side with both sides of my family was the contrast. I was able to see that otherness as a powerful thing and a cool thing. It's actually cool how different my mom grew up and my dad grew up. This should be celebrated. When you think about art history, American culture, the American dream, and what that actually means, I think it's a lot closer to these diverse families than anything else. I don't think that cookie-cutter mold is representative of the truth.

Your practice blends abstract figuration and surrealism. Why do you choose to portray your thoughts in this way?

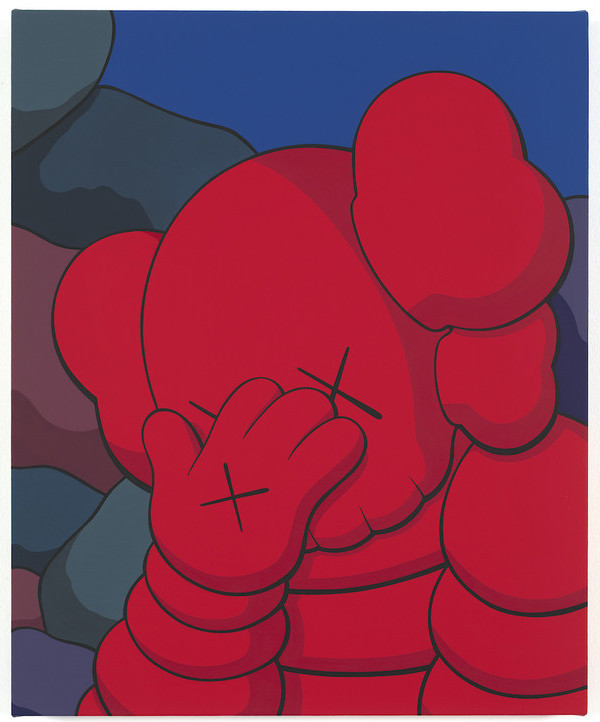

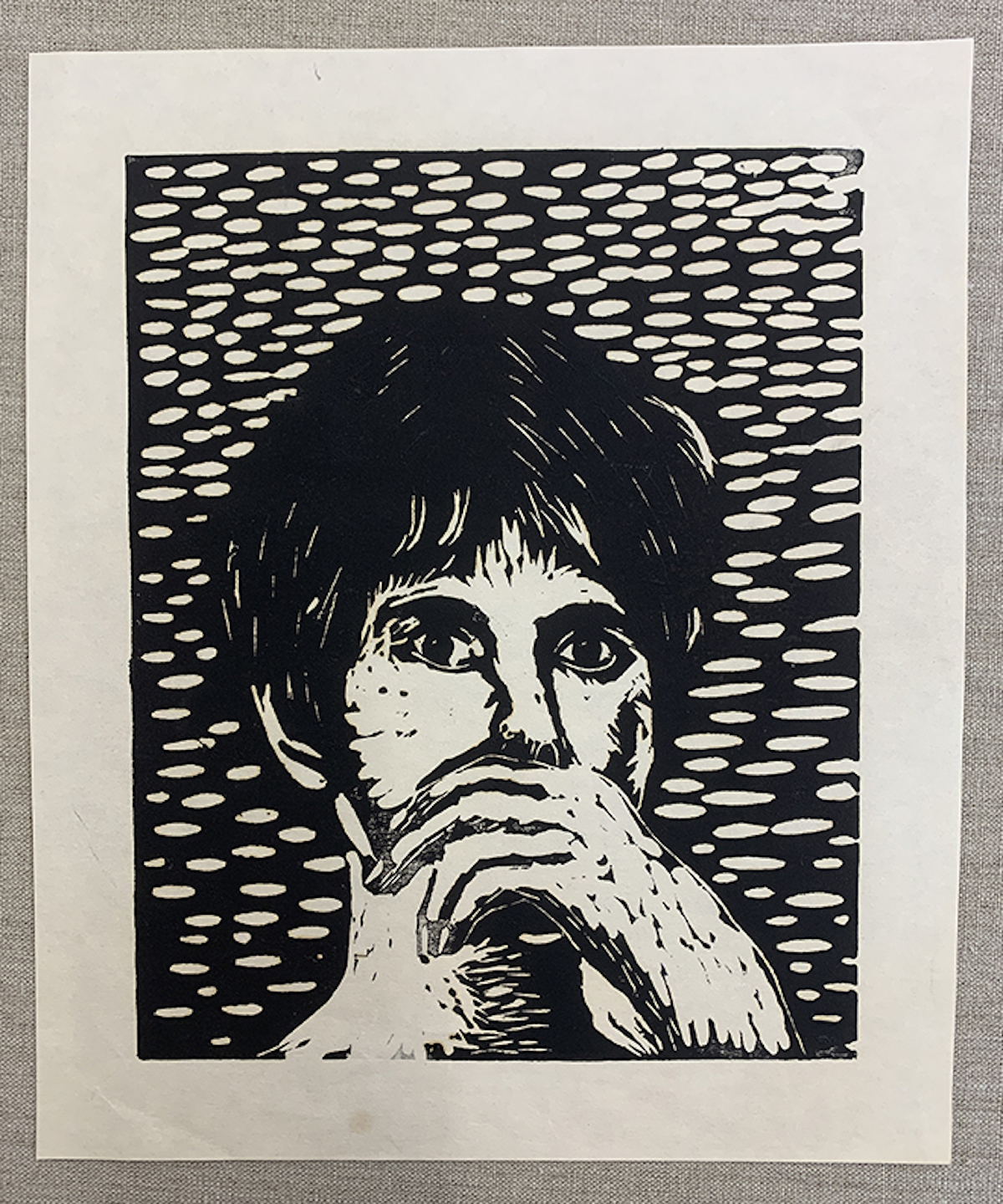

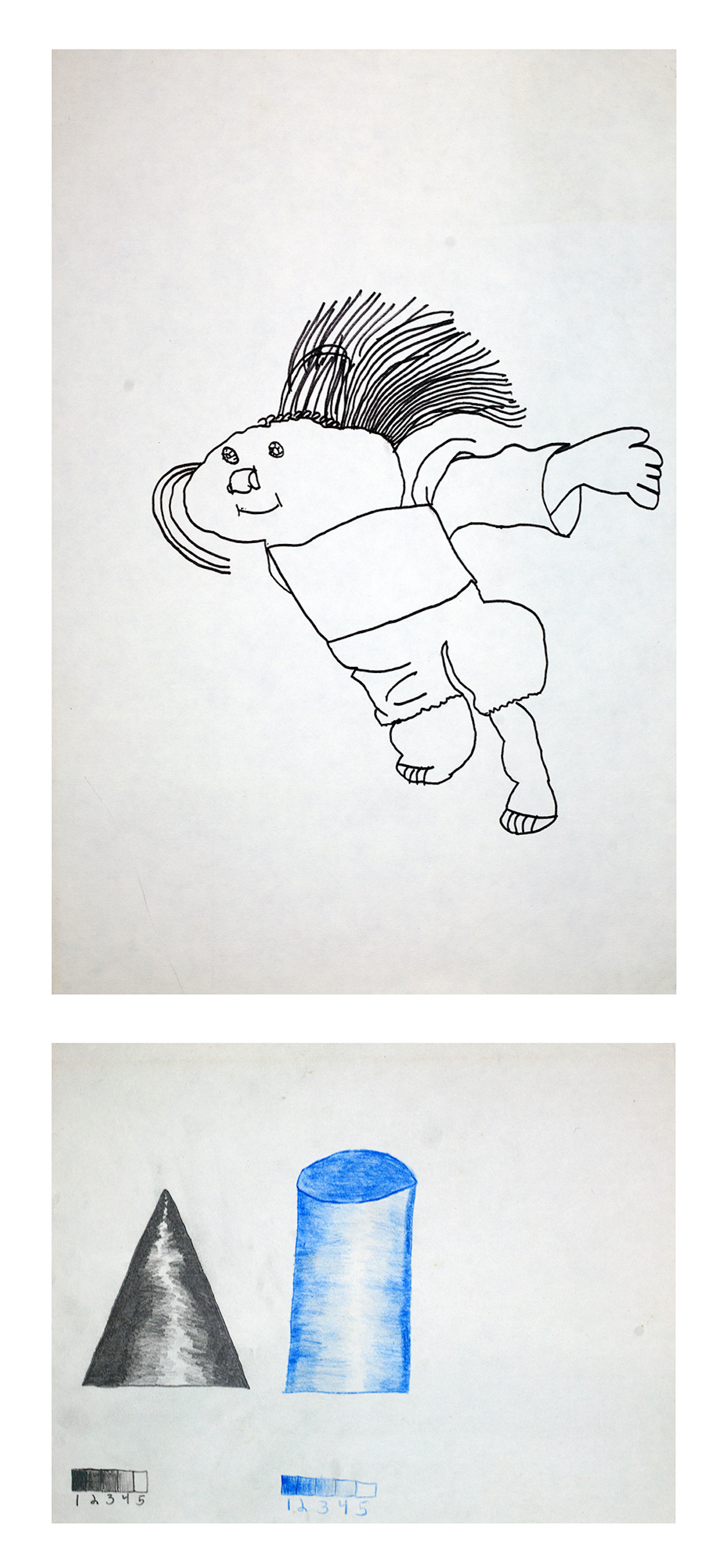

Stylistically, the choices exaggerate certain things and hone in on and celebrate the awkwardness and flaws that we experience at that age. I got my BFA and MFA and I was taught how to draw very traditionally. At the time, I found that to be super frustrating because I was never really interested in realism. Looking back now, I'm really grateful for it because I think it did help me develop my own style. All of the paintings [in this show] are mixed media, so I start with an acrylic base and then I end up layering a lot. But within the layers, I use acrylic and oil stick pretty heavily. For this series, I actually started making my paint for the first time. So most of the dyes are made from pigments and this was my first time experimenting with that. But there's also China marker, there's also regular marker, and even on the dog pile paintings, all of the girls have somewhat chipped nail polish. I actually did use real clear nail polish and glitter on them. And I'm telling you all of this because I think it also plays into what we were just speaking about. Being able to use high-quality pigments and very professional mediums, but mixing those with materials that I think can directly relate to adolescents, in a nostalgic way. Using hints of neon that almost remind you of a highlighter or using a little bit of a crayon and just employing these techniques that aren't traditional.

I know for this exhibition you have chosen a more muted color palette than you usually do and even the space you selected was intentional. Tell me about how this body of work departs from your previous ones.

This was my first time working on a body of work that was made in such a controlled setting, which was very challenging. It's the first time I have a show that's really site-specific. When you walk into the space, I want it to feel like an auditorium or a gymnasium. And the way that it's going to be installed is going to be that half of the space is red and half of the space is blue. This is definitely a bit of a jump for me being that it's a body of work that's all taking place within the same moment in time. Even the way that I made these works was interesting. It may seem a little bit different to my audience, but making them felt the same. It just felt like I was doing a series of studies, which is something that I usually do anyway. I'm just not really exhibiting the studies themselves, so this goes one step further. My last show, which was called Lost in the Dress Up Bin, also drew a lot of parallels from adolescent experiences to adulthood and navigating the space between girlhood and womanhood. I think that the parallels I made between performance and identity in that show are the same concepts I am exploring here. I am examining how women feel like we need to perform or that we subconsciously have an audience. We hold that gaze in so many ways and that affects our identity and how we view ourselves.