A Season in Hell with Sean Pablo

But he isn't. Right as I finish typing out the paragraph you just read in my notes app, the receptionist's glaring side-eye still hot on my face, I get two texts: (1) "Hey there," and (2) "Im at physical therapy." He tells me that he's really sorry, and that he'll be back in 45 minutes. I’m going to have to wait. Waiting isn't one of the first things that come to mind when you think of Sean Pablo. By the time he was 16 years old, he was sponsored by Supreme, Converse and the skater-owned conglomerate Fucking Awesome, after which, still with homework, tests, and a growing newfangled public image to be contended with, he was plucked out of the California State education system by his father to be homeschooled. Homeschooling — in major part because his dad made it a point to surround him with art and art books — fostered an already-existent penchant for creativity that prior public school experiences did little to nourish. Coming up on ten years after his first taste of such visionary autonomy, he runs a berserk all-out fashion brand, makes sparingly-released sad boy guitar music flanked by obsessive fans on SoundCloud, skates with just as much artfulness as he does hardcore flair, and, as of this evening, is looking to lug his legend up from the streets, and into the gallery.

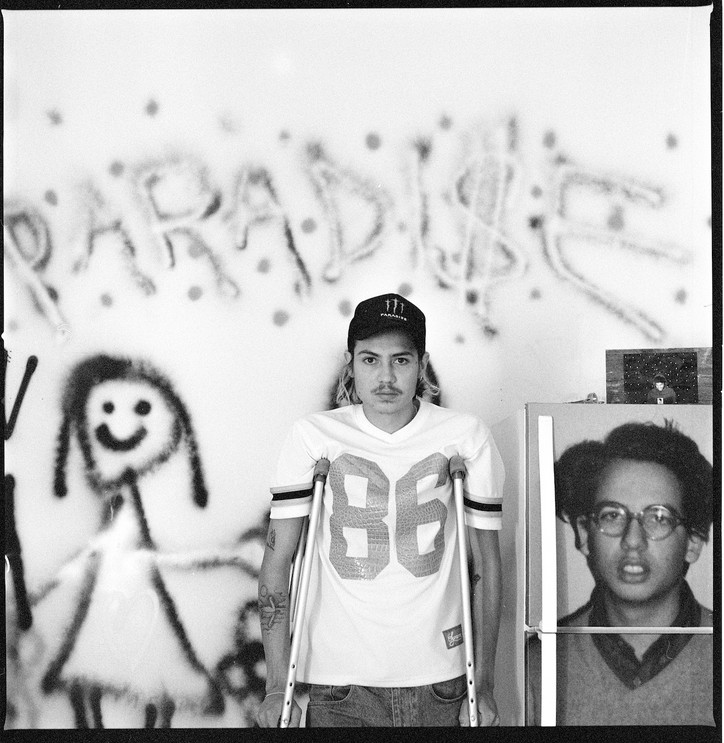

At around half past noon, the grand lobby doors are held ajar by an assistant, and limping his way through them on crutches is Sean, who hesitantly gestures towards me and begins uttering semi-whispered, too-cool-to-be-true apologies for being late. Lanky and aloof, he has the endearingly-awkward air of Joey Ramone, or at least a version of him that grew up in the Instagram era, looked up to XXXTENTACION instead of Iggy Pop, perhaps got his scars from failed tricks, rather than the fists of his bandmates. He’s wearing a light purple Supreme hoodie over a black Monster Energy baseball cap (the word “Monster” is replaced by “Paradise,” his fashion brand), brown-tinted shades, long gray sweatpants, tall white gym socks, and a pair of dress shoes that manage to work surprisingly well with his otherwise-cozy attire. Kinky blonde and black streaks poke out from the many agents anonymizing his face, and as much as it’s obvious to everyone in the room that he’s a star of some sort — though they don’t know for what — he slips into the space like any of the several sociable tourists who filtered in and out of the foyer while I waited, exchanging pleasantries with baristas, and telling seemingly every passerby possible to have a good afternoon. By the time we take adjacent seats in an expansive couch at the room's center, the receptionist doesn’t seem so suspicious anymore.

Sean sets down his crutches. “I have a broken tibia bone, and I got some ligament damage…” he explains. “...From getting hit by a car.” A couple of weeks ago, he was out skating in a parking lot in an Atlanta suburb, when a vehicle came out of nowhere and struck him, badly damaging his leg. This morning has been hectic. He hasn’t had breakfast yet, and his mom, who elicits a charming Forrest-Gump wave from him when she walks by us in the lobby, had to remind him of his physical therapy appointment. He’s ecstatic when a Chick-fil-A delivery man toting two large white plastic bags wanders with searching eyes into the corridor, and for the rest of our interview, he’s apologetically poring over a bowl of macaroni & cheese, accompanied by what I think is a large Sprite. He’s in a constant rotation of taking the shades, hoodie and Paradise cap off and putting them back on again, and he speaks in quiet, distant sentences that feel in equal part genius, stream-of-consciousness, press-shy, and vaguely disinterested. It’s very difficult to distinguish between the four at any given point.

Tonight’s exhibition opening comes at the tail end of two decades spent taking in a slew of rapidly-changing surroundings, boasting the undertakings of an artistic eye incubated amidst what’s probably one of the more interesting come-ups among America's 24 year-olds. He grew up in the fabled Fairfax of Tyler, the Creator and Odd Future, flocking with like-minded skaters, and, at least up to the point of his senior year homeschooling, skipping high school classes to haunt the streets of Los Angeles with friends. Though his mom is an educator herself, she was supportive enough of his creative endeavors to give him the room he needed to grow, and by the time Supreme sought him out — he speculates that fellow skater Sage Elsesser may have put in a good word for him — any inkling of an instance that could have been spent looking back was long gone.

Over his meteoric ascent from scrawny teenage shredder to masterful multi-hyphenate, as life has moved faster and faster, his art has been the chief agent in helping make sense of the ever-growing list of things on his plate. “I’ve always wanted to do a photo exhibition,” he says. “And it makes sense, because I’ve been shooting photos since I was a young kid, so it was always something I wanted to do. It’s crazy that it took a long time. It’s all photos from my past, and it’s about the whole time that I’ve been, like, in the public eye.”

Because of how quiet he is, both in-person and on social media — his Instagram is composed mainly of artsy photos of his homies, with the occasional cryptic billboard or street sign — to some extent, Sean’s image in public perception is chiefly informed by the way he appears in skate clips. It’s terrible journalistic practice to cite tweets in articles, but if there’s any certain one that should be permitted to break the rule in this context, it’s probably one that speculated, in 2019, for two hard-earned likes, the following: “I’ve never heard Sean Pablo’s voice but I assume it sounds like Him from Powerpuff Girls.” (It does not.)

In most skate videos he’s featured in, besides, perhaps, horny old women who declare that he needs to “bring it down the pipe to mommy,” much of the conversation both from and around him is hushed. He skates with a trademark glare, kickflipping somewhat menacingly over unsuspecting garbage cans, all the while maintaining a certain graceful control that makes it all seem imposingly mechanical. “I guess,” he says with a chuckle, asked whether he thinks people may see him as somewhat ominous, “maybe when I’m skating I’m, like, concentrating so hard, so it looks like maybe I make a weird grimace or something.”

It’s an interpretational ambiguity that, come tonight, he’s looking to replicate with his artistic practice. When I ask him what he wants his work at the exhibition to do for other people, it’s one of those moments where you can’t really tell whether his words are the result of genius, a steady stream-of-consciousness, press-shyness, or vague disinterest. But if anything, they're honest. “I don’t know,” he starts. “Hopefully it can convey my life, and the way that I… see stuff. I don’t know, honestly. It’s really hard to say. What I want people to think? I don’t know.”

Sean Pablo’s analogousness to Joey Ramone goes beyond aesthetics and soft-spokenness. His own music — “Maybe a little Lil Peep influence… maybe The Cure… Joy Division maybe… I don’t know, maybe for all those things to get mixed together,” he tells me, when I ask him what a Paradise album might sound like — much like the gangly punk rock pioneer’s late-career solo stuff, rings torrentially, unapologetically emo, and it’s an unmentioned shame that there isn’t more. “You used to be my anti-depressant,” he groans, over layered, ultra-reverbed guitar strums, in his most popular SoundCloud loosie. “Now I be taking antidepressants.” Corny to some, but on-brand for skateboarding’s lanky boy next door: if being hit by cars, missing breakfast, and limping your way back to a hotel to meet pestering journalists was your day-to-day, you’d probably be singing about anti-depressants, too. In trying to explain to him how he’s a lot like Joey Ramone, I trail off mid-sentence, stammering my way through something along the lines of On the outside, you’re both kind of imposing and hardcore, but deep down…

“The greatest person ever,” he concludes, with a boyish grin.

Five hours later, I’m at 17 Allen Street, but it turns out to be the wrong 17 Allen Street, because no matter how much I try to reason with a pair of shop owners adamant that their kitchen hardware store is closing, they look at me like I’m insane when I ask how to get to floor number two, and after about a minute or two of this, they resolve to ignore me — as, in retrospect, I, too, would have — and I’m awkwardly pacing the intersection of Allen and Canal, gesturing towards the closed kitchen hardware shop, annoying strangers with frantic questions about how I’m supposed get to floor two, all the while wondering with dread whether I misread the address on the advertisement. The minutes are counting down to opening time, and out of the throngs of bystanders trudging to and fro along the corner, the ones who have come for the event are somewhat easy to pick out. They’re aimlessly pacing the gallery’s surrounding streets, looking up from their phones at the slightest bit of a hint that the doors might be opening, posturing with crossed arms in ill-executed efforts to appear as if they know what’s going on. An increasing number of kickflips can be heard slapping against sidewalks as the moments pass. Around me, there are about a dozen different variations of beaten-up Adidas Superstars.

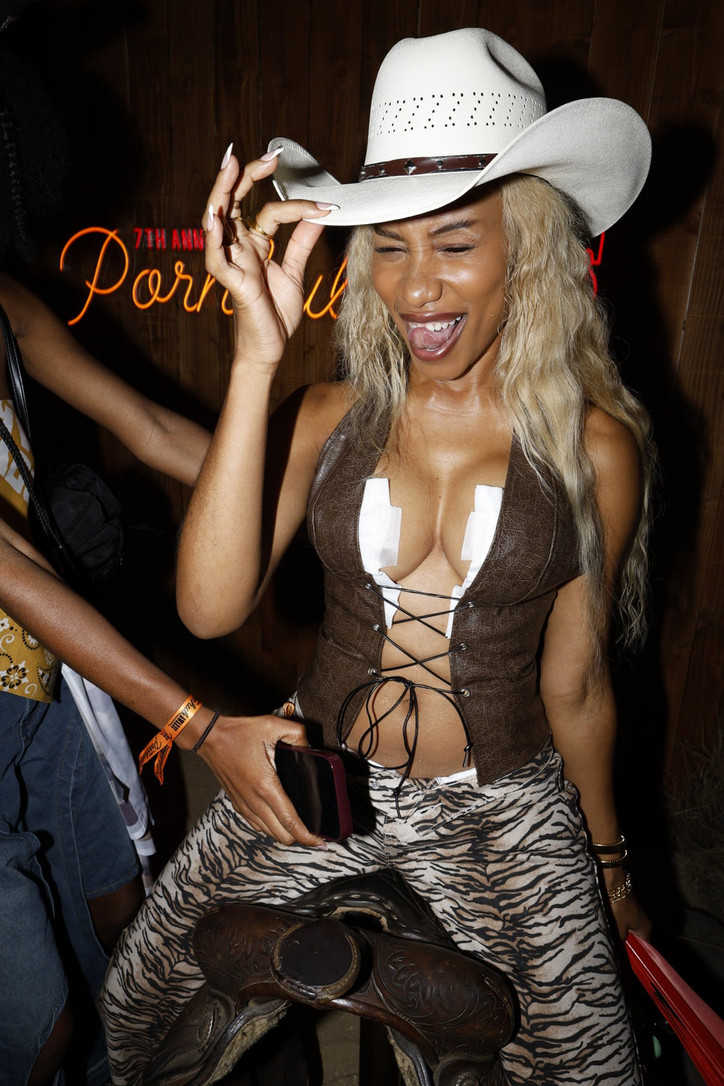

A few minutes after the show’s originally-scheduled start time, a fashionable gallery assistant somehow rocking Adidas track pants with bright purple socks and dress shoes opens the door, but with the caveat that the space isn’t ready yet, and it’s going to be a five to ten minute wait. For anywhere from about half an hour to forty-five minutes, I’m standing against a wall in a small, dingy lobby area, shared with a rotating cast of eager characters who come in, get the apologetic spiel about the show starting late, opt to stick it out in the impromptu waiting room, give up and go outside for fresh air, then repeat the process. It feels a little bit like that one time Kanye announced a surprise make-up concert in this very city, got a bunch of A-list cultural figures to stir up hype about it on Twitter, and then ultimately no-showed. “I saw it on some [Instagram] stories,” one bike rider in blue shorts tells me. “So I was like, ‘Yeah, I gotta come.’”

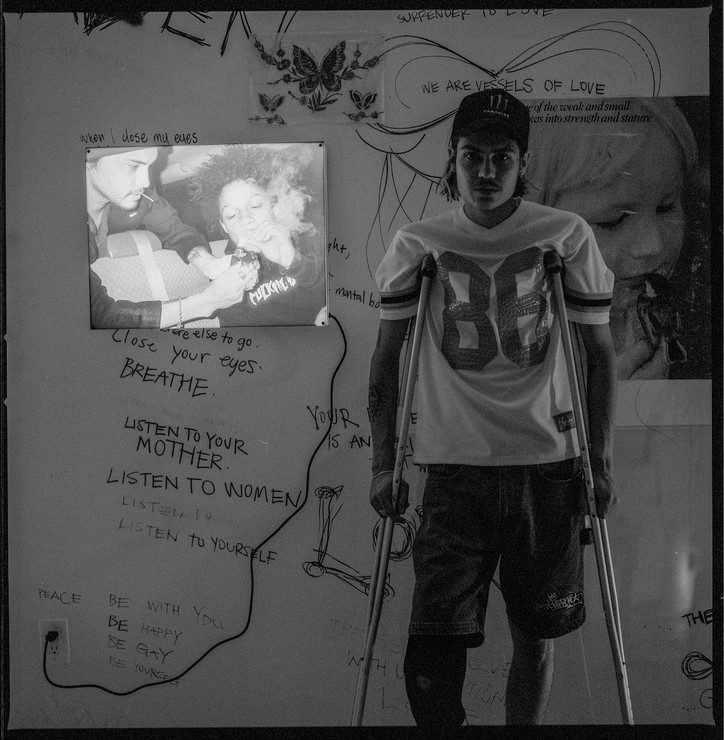

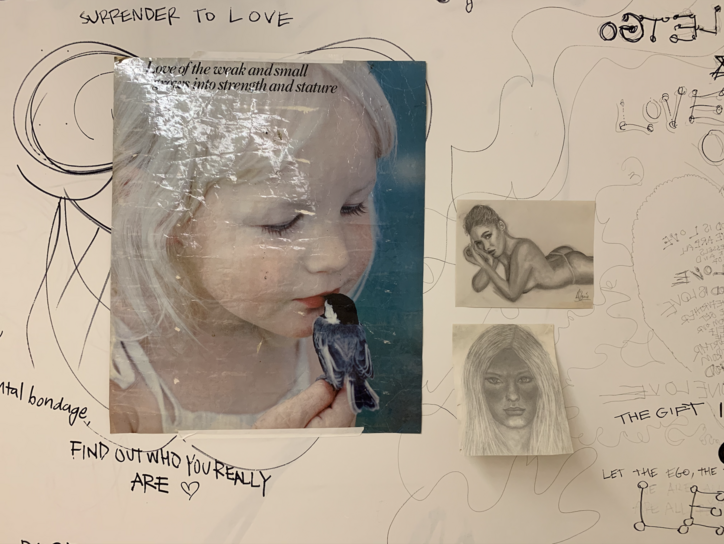

But Sean Pablo is no Kanye, and at about quarter to seven, we’re ushered up a dark stairway, and into a modest-yet-intimate gallery setup that looks a lot like someone gave an emo stoner a full calendar year to decorate a university dorm suite. One entire wall is dedicated to various hand-drawn renderings of women in various stages of nudity, save for the occasional grinning Mickey Mouse or conglomerate of cartoon skulls. Behind an ominous doorway with “ENTER HEAVEN” scrawled just as ominously in thick black spray paint that coats its perimeter, there’s a dark room with a single chair in its center — the kind a grandfather with old-world values and a Wall Street Journal subscription would die in — and on a large sheet that doubles as a makeshift projector screen in the front, a video featuring gyrating men, knives, ambiguous gatherings and motorcycles is on endless repeat. Besides “ENTER HEAVEN,” other scrawlings on the wall, alternating with subtle chaos between spray paint and jagged marker, include “HEAVEN IS ALWAYS HERE AND NOW,” “LISTEN TO YOUR MOTHER,” “LISTEN TO WOMEN,” and “LISTEN TO YOURSELF.” On another wall, under the smiling supervision of a spray-painted penis doodle, prints of photos Sean took of his friends are stationed adjacent to one another, at some points interrupted by larger images illuminated by bright lights that have been installed behind them. A popular corner features three mini-TVs stacked atop one another, each little screen playing cult-evocative footage — Rob Tyner of MC5 falling into crazed mid-song spasms, a televised church service in which parishioners flail around like ragdolls, a gruesome murder scene in a slasher film — that drones with no end, cueing curious visitors to stare, and then awkwardly wander away once they get bored.

Earlier today, back at 9 Orchard, Sean broke down his interplay between Heaven and Hell like this: “I think it’s just the idea of Heaven as a funny kind of motif. And obviously Paradise kind of plays on that. Because with religion, the idea is that this life isn’t important; it’s what’s coming in the afterlife that you should be concerned about, and that’s why you should do this and that. I think you should live in the moment. And appreciate the moment. I’m not saying one thing or another. It’s just however you want to interpret it.”

Tonight at the show, the open-endedness seems only to result in more questions. When, in the aforementioned grandpa-couch-projector-screen room, a pair of loud long-haired 20-somethings let out a boisterous laugh, and one turns to the other and says “This is crazy,” it’s hard to tell whether they’re laughing with the show or at it. The air of the gallery is rife with trepidatious intrigue, and many of its inhabitants seem to have shown up out of curiosity from the slew of large accounts that promoted it on their Instagram stories today. This event seems to be a good portion of the crowd’s first art opening — the biker I spoke to earlier thought it was the premiere of a skate clip — and for the small demographic that appear to have been experienced in this sort of thing, they certainly haven’t been to one informed by Sean Pablo’s inner machinations.

But by the time he arrives, still on crutches, and flanked by gallery workers, it seems like he wouldn't have it any other way. He’s wearing a white Supreme box logo tee, a beaded necklace, dress pants, and the same tall white socks and black dress shoes as before. Puffing on his vape every now and then, he blends in the same way he did in the hotel lobby. Either that, or most people are just scared to talk to him. He poses for a photo here and there, and eager followers, many of which are likely still populating the comments sections of his year-old SoundCloud loosies, nervously encircle him, almost as if to wait their turns to offer anxious, rushed, “congrats dude”s. When I catch him near the corner with the stacked mini-TVs, he doesn’t have any complaints besides the fact that he wishes the audio could be a little louder. I would put a quote here, but whether it’s because his voice is too quiet, the people are too loud, or both, my tape recorder picks up nothing.

Outside, flocks of punkish young adults are dispersed as loosely as they were an hour or so ago, when no one knew whether the show was still happening or not. I spend several minutes tapping a few nonchalant skateboard-toting high schoolers on the shoulders, their disinterest in me only seeming to grow when I ask if they’d be down to answer a few questions about the opening. “It was really interesting,” Michael Mankong, a polite videographer from Brooklyn, tells me. “I watch a lot of their videos from FA and Supreme, and it’s cool to see little photos and Sean’s art. He has it on his Converse sneakers. It’s cool to see it more intimately. [...] I feel inspired to maybe in the future do something like that for myself and my friends.”

The easiest way to gauge how people generally responded to the show is to spend five minutes in the room with the couch and the projector. When I do, everyone is vaguely annoyed at me because, as I realize in retrospect, I happen to be blocking the entrance to a refrigerator containing cold drinks for the taking. The space, much like the stacked TVs, can be conceptually condensed into an experiment in attention spans: one by one, people wander in through the ominous doorway, hesitantly find places for themselves in a haphazard line slinking along the walls, stare, chuckle, stick around until it feels awkward, and file out.

At some point, the fashionable gallery assistant with the purple socks flashes a playful smile behind the chair, and sitting in it is a little girl, no older than five, who is hysterically laughing. She is the only human being present who isn't actively treating the spectacle like a church service. You can’t help but wonder if there’s a certain type of person best fit to appreciate Sean’s art, or, maybe, a right way to react. And by the time the lights are off, the gallery is closed for the night, and the kickflipping high schoolers on the sidewalk have gone home for good, the only applicable prognosis is that, just like celebrities acting in theater, it all depends.