The Seriousness of The Soul: Reginald Sylvester II

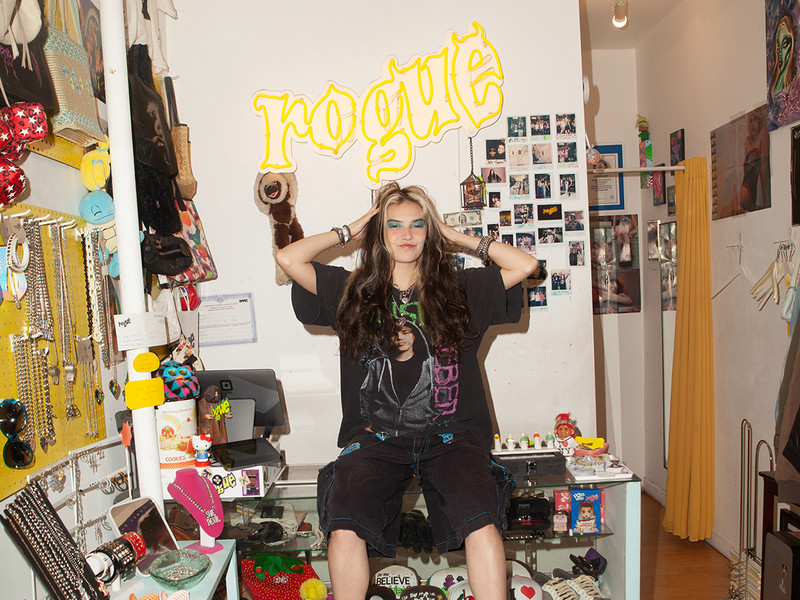

(Above) Hat and sweater by LOEWE, vest by JACQUEMUS

Inside that space, Sylvester has recently finished his latest series—aptly referred to as his ‘Soul Vs. Flesh’ paintings—a sort of culmination of his career thus far. The works are sprawling, lawless pieces that touch on religion and historical trauma in a way that’s true to Reggie’s own understanding and engagement with the idea. But there’s also an undeniable and inherent beauty, from the color palette to the controlled mania of his strokes. It’s a concept that both Mack and Sylvester can relate to—one they discuss openly in the latter’s studio—that as Black artists and creatives in our societal landscape, they fight to summon meaning from their scars.

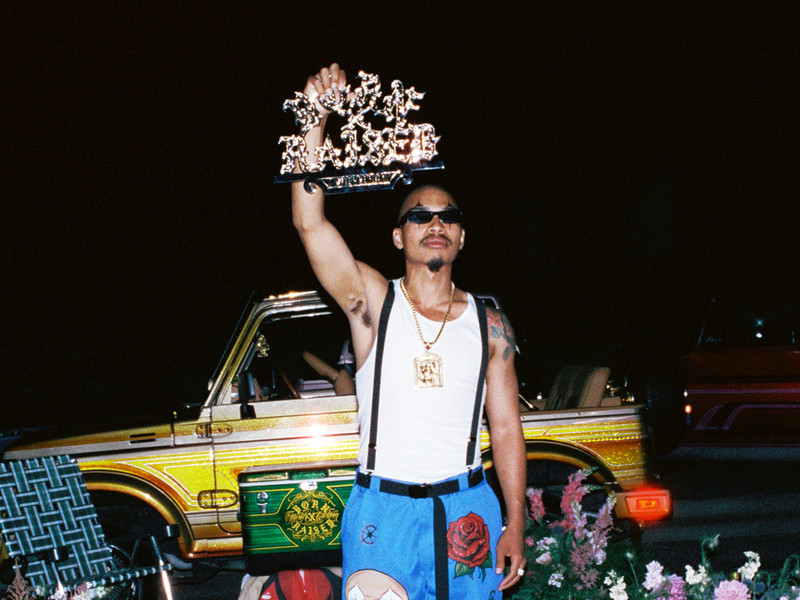

Left - Coat by COMME DES GARÇONS HOMME PLUS, shorts by LOEWE, shoes by CLARKS (Reginald’s own).

Right - Hat by NIKE, glasses by RETROSUPERFUTURE, shirt by MARTINE ROSE, belt and pants by A.P.C., shoes by CLARKS (Reginald’s own).

ERIC N. MACK—Did you go to museums as a kid?

REGINALD SYLVESTER II—I didn’t go to museums at all—I wasn’t versed in art as a child. The only reference point I could really make was my father. He was a graphic designer and typographer. So, I would see him sign-painting and taking comic strips and blowing them up tenfold and repainting them, and just always creating and working with his hands. When I think about the palettes my dad worked in—black, white and green, and yellow—and now looking at some of the paintings around here, those are the colors that I am naturally drawn to when I’m just selecting and going in.

EM—I hate this question, but how did you begin this series? Did you have a conceptual or emotional space that you wanted to project as you were painting?

RS—I really just picked up where I left off. My last exhibition, in my opinion, wasn’t my strongest. So, when I stepped back into the studio, I knew there was going to be a big change, and I knew I still wanted to use the totality of the figure, but I wanted to get to these abstract pictures, and I didn’t necessarily know how. My basic process is to build and take away. I just kept editing myself and editing myself, and I came to realize, ‘Well, actually let me go back into the exhibition that I felt was my strongest,’ and that was the show I had in Milan, The Rise and Fall of the People at Fondazione Stelline. And the strongest work I had in that show was actually made from less—less colors of paint, less materials. In that show, the figuration was a lot more elusive. So I started to use the exhibition as a basis to further investigate and explore.

As I started to do that, I started to actually be more judgmental and pick apart parts of the painting that I felt were weak, and parts of the painting that I felt were the strongest. I would pick those—whether it was a corner or a center area—and I would take that area and expand on it into the next piece.

Slowly but surely, I started to see this relation with these war-like, abstract figures I was making, between where I was in my life at the time. These last 10 months I’d say, has been me just really battling with myself on the things that I’ve been reading and interacting with through scriptures in the Bible and how I’m living my life. And that gave the work its meaning and context. That, and me deciding I wanted to use less of the figure and be more suggestive. The more I suggested, and the more that it alluded to these more abstract pictures, the more confident I really got with my hands.

EM—Totally. So, there’s a palette, and reducing a palette produces some of the terms. But also, there’s an interesting contradiction where there’s the reduction of the palette, but then they’re these maximalist overall paintings.

RS—What started to happen was, once I started to get more confident with my hand, I got more confident in covering the full surface of the work. And also the decision-making became stretched out. I made a lot of those earlier paintings with a more simple palette, and in one sitting. But these vertical, more abstract pictures, I actually started to live with them a lot longer, and it would take a lot more energy out of me too. But definitely, the reduction has always helped me evolve in some weird way. Making work with less has always helped me push to get to that next place. It’s very strange, because the works that are in the exhibition—those were made in sessions, and now I’m back to a place where they’re made at once. I guess that’s me being more confident and understanding my hand. I think it also has something to do with how I came up with the title of the show, Nemesis, because I felt like it tied into the idea of the soul versus the flesh, the spirit and the physical, and that we are our own biggest enemy, in some way, shape or form. That’s just been my life, man—these trials and tribulations, and painting really just allows my spirit to speak about the internal battle I’ve been having, and also the struggle that our people have been having as well, because I feel like we’re all connected. It’s all just a big chain gang.

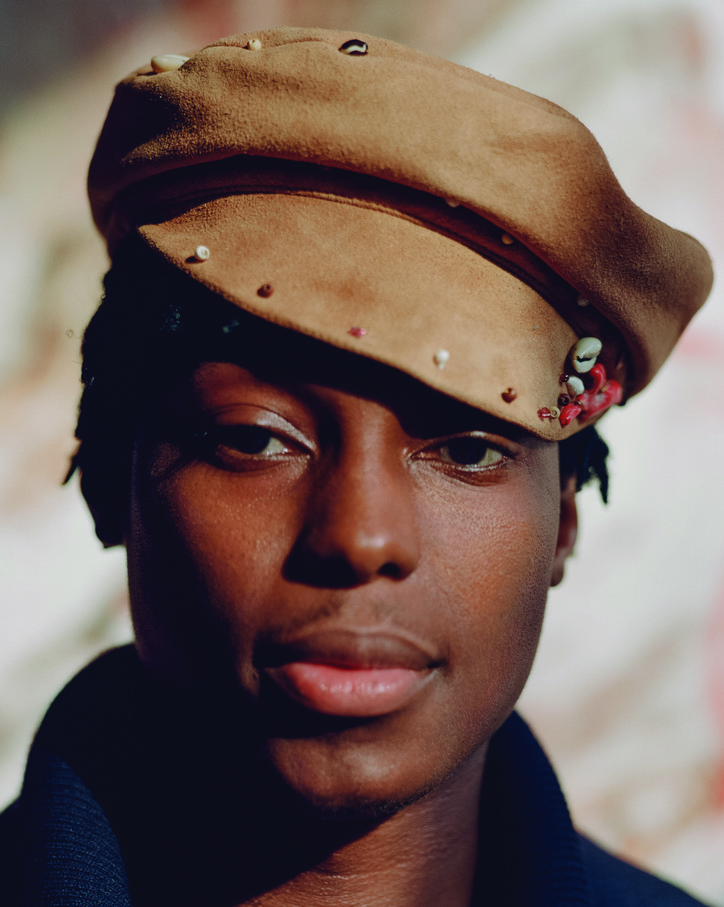

Left - Hat and jacket WALES BONNER.

Right - Sweater and pants by LOEWE, shoes by MARTINE ROSE.

EM—That brings me to my next question: Can you speak to your intended viewership? Who is the intended audience for these paintings, this exhibition? I love thinking about your work having come so much from your father’s, and I imagine he would be somebody on your list.

RS—Yo, hugely man. Hugely. Me and my pops, it’s so great, because I feel like when you’re a kid, you idolize your father, and then you go through this—at least, for me, I went through this stage where I resented him in a weird way and held this grudge against him deep down. Now, the conversations we have are so in tune with the work and so in tune with how we as a people are being treated around the world, and just the systematic barriers that are set up against us, and that have been so detrimental and so influential to the world.

RS—Overall, my introduction to abstract painting has been through the abstract expressionists that lived and worked in New York. But to be honest, the more I’ve educated myself and the more I’ve learned, I get hungrier and hungrier for more painters that are representative of who I am, and my background and where I come from. I’ve always wanted to be a representation of my tribe—our tribe—through abstract painting, and I just never necessarily knew how to get there, and I didn’t necessarily have the knowledge of the forefathers before me that were doing it. I’m just now starting to find out about Raymond Saunders, and Jack Whitten. Or even—

EM—[Robert] Colescott, or—

RS—[David] Hammons—all these guys.

EM—Gilliam.

RS—Yeah, Sam Gilliam. I’m so novice in this area and this range, but I know that I’m speaking to somebody that spoke before me that looks like me. Because I want to speak to the Black and Brown person living our experience through abstract painting. I know I’m not the first to do it—I know I’m not the only one doing it right now—but it hasn’t been necessarily celebrated. So, I don’t want to leave anybody out, but when I think about these works, they’re spiritually meant for Black and Brown men and women. That being said, they can still be relevant for every other race and every other person on this planet.

EM—It doesn’t diminish that. It’s just that these images need to connect to the people that they’re about, and Black folk need to be remembered and celebrated.

RS—Yeah. When I’m making this work, I’m listening to “American Dreamin’” by Jay-Z or “So Many Tears” by ‘Pac, and I listen to those records because they almost touch on, not so much the trauma, but the lack of that we have in society. And I’m thinking about the state of our people. Some of us might be good, but the majority of us are not, and I try to lock myself into that emotion in order to get in touch with my own pain, and to touch on the pain of others that look like us. I hope that by trapping myself in those emotions, and reflecting those vibrations onto the surface, I can facilitate the means for people to pick up on that when we come face to face with the work.

EM—I feel like there’s a basis of trauma, and a lot of people would say that that would be the pressure that would produce a diamond. But I think there is, in spite of it all, the traumas of today and yesterday as they were directed to African American folk, Black folk of the world, Brown folk of the world, the importance of focusing on structuring aesthetic, thinking about beauty, being allowed to produce and find something of beauty made out of—

RS—Made out of pain.

EM—And coming from nothing but aspiration and intention, which identifies that maybe there is no such thing as a deficit. It’s not about a deficit or an emptiness, but a kind of beautiful potential. I remember years ago watching this Philip Guston interview, where he talks about having ghosts in his studio space, and in his images, and it being a process of the works exorcising the ghosts in his paintings. And when the ghosts leave, he’s left with himself—and that’s the connection to the works that he finds most meaningful. So, I guess it’s a question about influence, about the anxiety of influence— the ‘there’s nothing new under the sun’ train of thought, on which I beg to differ, especially with us. But…are there ghosts in your studio?

RS—You know what, yeah. Because I’ve definitely been speaking to Max[imillian William] like, “Yo bro.” When I’m in the studio, I know my painting forefathers, or even some of those original mark-makers that were us, that I may not even know about yet, I feel like they’re with me. From a de Kooning or a Twombly to a Jean-Michel [Basquiat], or maybe some ancient forefathers—we all have that connection. But as far as influence, I feel like the career that I’ve had so far with painting, I’ve always been critiqued on influence. “It looks like this, it looks like that. He’s trying to be this, he’s trying to do that.” But really—

EM—That’s anybody.

RS—That’s anybody! You fight through the influences in order to find your true self, which kind of reminds me of what you’re saying with Guston—maybe those ghosts were his influences hovering over him until he painted his way through to get to something that was truly left—himself. I feel like I’ve been battling to get to that, and I’m just now being able to get to that space, because now, when I’m going into my work, I’m not necessarily thinking about my painting forefathers from their imagery. I’m more so thinking about them from their perspective and from the life experiences they had in order to make the work that they made.

EM—Right. Like a kinship.

RS—Exactly. And I’m more hungry for that now too, now that I have a better understanding of my own practice. Do you feel the same?

EM—Yeah, definitely. Unfortunately, the difficulty with that question and the reason I say it with some hesitation, is because I think it’s been used as a means of critical dismissal of young Black artists historically.

RS—Say it again!

Left - Glasses by RETROSUPERFUTURE, jacket by CARHARTT WIP, shirt by MARTINE ROSE, shorts by JACQUEMUS, socks by UNIQLO, shoes by NIKE x SACAI, hat Reginald’s own.

Right - Hat and jacket by WALES BONNER, pants by CARHARTT WIP, shoes by CLARKS (Reginald's own).

EM—For people who refuse to criticize the work, they tend to talk about what it looks like or how it’s already there, how it’s already a part of a conversation, which ends up negotiating on meaning in the market rather than meaning in the artistry books. There was a Jerry Saltz article reviewing the [Whitney] Biennial, and he just scooped up four to five of my peers, Biennial Black artists, and just talked about them as riffing off of Rauschenberg. I also remember going back and reading early reviews of Sam Gilliam’s work, where they completely slammed him as being parody—that’s the worst of all. Our history is an image, and the after-effects are so much more complex than an LOL. But people—it seems like they tend to try to disengage the bomb.

RS—It’s funny you say that, because Roberta Smith made a comment about my work, referring to it as a Basquiat- Picasso fusion, and I felt like that was just lazy. When I hear you say that about Gilliam, or even your peers at the Biennial—listen, my biggest thing with that whole shit is we’re the original mark-makers. But all these artists that aren’t of color, like Picasso, get praised for taking away from things that we originally made, and it’s labeled as great. Or even the abstract expressionist movement—their work was called aggressive. It was considered to be manly in a good way, then Jean-Michel hits the scene and he’s primal. Why can’t it just be aggressive or manly work too?

EM—But it’s also really all about resilience and pushing through those barriers.

RS—Do you feel the fact that Gilliam and Whitten, and the other OG from London—

EM—Bowling. Frank Bowling. And Norman Lewis.

RS—Yeah, all those guys. Do you think that them getting the respect they’re getting now, do you think it will make it a little easier on us? Or do you think they’ll always try to disengage? Because that’s my biggest thing with this body of work that I’m making. I’m like, ‘What can you say now? I sat out a year and a half, I didn’t just keep making the shit that I was making, I pushed my limits as far as I could push them. Are you going to disengage?’ I mean, they put you and your peers in the Biennial. Are they going to continue?

EM—Well, just the framework of a show like the Biennial and how people experience it—where there are 70 or something artists—there are these quick judgments and quick distinctions. But they are making those judgments and distinctions within the institution of the Whitney. So it’s like, no matter what you’re going to say, somebody’s going to review the show and be able to speak to either the individual identity of the works or the meaning. But the fact is, all of these references I’m thinking about—Guston, Gilliam, all of these OGs that are now running up on this bluechip establishment, people that we’ve always known, like Betye Saar and Faith Ringgold—there has been this intense suppression or marginalization of these voices, and now it’s being celebrated and brought into a new light.

RS—At the end of the day, it’s about being relentless in our practice—to just keep going. At the end of the day, great work speaks.

EM—That reminds me, this might be a leap, but how does fashion relate to your life and practice?

RS—I’m really influenced by fashion just because I want to be fresh. But on the other end of that, I think of how I’ve been able to speak to fashion in the sense that I’ve always been interested in textures and colors and fabric, and I think when I started to make paintings on canvas—especially on stretch canvas—it almost felt like I was working in a way in which maybe a seamstress might be working with a piece of fabric. Because you have that freedom of folding and stitching and moving things—that freedom with the form of the fabric. Definitely my favorite brands would be Comme des Garçons and Margiela—those are two brands that I see influenced by the medium of paint, and when I think about Rei [Kawakubo], I’ve always just loved her approach—it’s very radical, in a sense.

EM—Are you empowered by contemporary fashion? Do you feel like there are designers considering you?

RS—I’m empowered by the camaraderie between fashion and culture. And I’m empowered by that door being kicked in a bit, so that fashion and culture have been able to mesh in a way where it’s more about community, and it’s more welcoming—even the industry is a little bit more open. But when I think about the art world, those barriers are still there. Art spaces and institutions need to continue to open up, because I’ve always felt like—you know the term ‘art imitates life?’ Well, how much of this art is really representational of culture and what’s really going on? In fashion, I think it does—or at least it’s started to—and I just wish that same empowerment would translate to the art world. But I also think that a lot of these fashion houses need to pay attention to more art. It’s happening, but we need—

EM—For the houses to acknowledge what they’re paying attention to.

RS—Yes, and don’t take. Don’t sit here and take, please. Because if you can open the door to street culture and streetwear, you need to open up to these artists that are around you, that you know you’re being inspired by— the artists on your moodboard. I can definitely say that you’re on a whole lot of moodboards, and others like Tschabalala [Self], as well. These houses need to just be like, “Look, these are the artists that are actually creating on a level, give them their due.” Or at least bring them in and don’t act like you’re not noticing what the fuck is going on. Because it’s happening, and if the real art world is taking notice, then you damn sure should be taking notice, too.

EM—Yeah, definitely.

RS—That’s why I haven’t been too pressed to do anything with brands—because I feel like, if that opportunity ever came, I genuinely want to work with somebody that’s making great clothes, but is on the up and up. Somebody I can see more as a peer, or as an extension of what I’m doing. Like, I see what Sam Ross is doing, I see what Kenneth Ize is doing, and that would make more sense than waiting for some big house that’s been ignoring my contemporaries, you know?

Left - Hat by NIKE, glasses by RETROSUPERFUTURE, shirt by MARTINE ROSE, belt and pants by A.P.C., shoes by CLARKS (Reginald’s own).

Right - Sweater and pants by LOEWE, shoes by MARTINE ROSE.

EM—Right. We’ve previously talked about abstraction and faith, which I see as a really concrete link for me. Abstraction as a vehicle for faith, and the relationship between the painting object and the body of the artist—that it brings its own dimensions, unseen structure, resonant beauty, transcendent communication and distinctions in light referring to a physical space that’s also emotional. What do you think?

RS—I believe the definition of faith is evidence of things that are not seen—I probably murdered that, but I’m pretty sure it says something like that in the Scriptures. So, for me, going into abstract painting, there is no evidence of what’s going to come at the end of the journey of making the picture. But that’s the beauty of it: having the faith that you’re going to find that picture, that unconscious image. On a larger scale, it’s about having some type of faith that if I keep these certain laws and these certain commandments, that there is a promise in the end that there’s more than the end. That connection for me—it’s made the Scriptures that much more real, because painting and making abstract pictures has been the tangible evidence of that. You know? Just having the faith to come into the studio every day, to keep putting my emotions, my struggles, and my trials and tribulations on the line in order to build these surfaces. I feel like it’s the same thing, and how I try to live my life—making mistakes, learning from those mistakes and trying not to make the same ones again, so that I can get to the heaven I want to get to. Paintings, even for me, are about honoring Him, because I think the most ultimate gift is to be able to create. That’s what I bring into the studio every day—that’s what motivates the work.

EM—I might have asked you this before, but did you see the Aretha Franklin film, Amazing Grace?

RS—I should have, but I still haven’t watched it.

EM—You have to see it. I bring it up because she was obviously raised in the church, and began to sing in the church, because her father was a preacher. But the documentary functions as this way of her resolving some of the tension between the pop, secular music she sang, and her past and upbringing in a gospel choir. But there’s a part in it where Reverend James Cleveland speaks about the title track, “Amazing Grace,” and the Civil Rights movement, and the riots, and how he didn’t think they would ever experience the beauty, or happiness, that they have. So, there’s still pain, there’s still strife, but there’s this document of Aretha at her best, and I feel like you could definitely connect with it, because emotionally, I connected with it too—just seeing a room full of Black folk witnessing all these different types of aesthetic transcendence.

RS—Yeah, for her to make something or sing something so beautiful in a time that was hectic as hell for us, I think that’s interesting, because I really do feel in my heart that it might be worse now than it was then. I always have this conversation with my mom, and it’s because back then the shit was in our face. So, we as a community grew more tightly knit. But now, those evils are hidden behind so many curtains, and I feel like, if somebody doesn’t like you, you’d rather just know it, versus them secretly feeling some way about you. I was talking to my homie Anthony [Jamari Thomas] about this loud silence. We feel it in the air and we feel it inside, but it’s almost like a dog whistle—like it’s being blown but only certain people can hear it, or maybe only us, as Black and Brown folk, can. And I think that’s why we’re creating at the level we’re creating. It’s important to be aware of the times. I feel like my friends always think, ‘Here Reggie goes again,’ but I do feel like we’re in the last days, and it’s imperative that we touch on the seriousness of the soul, the spirit and where our soul or spirit resonates with the world. There’s a lot of struggling going on right now, but when you look at the majority of that struggle, it’s in our areas, in our countries, in our communities and homelands. But I think that’s Him putting pressure on us, so that we can ultimately turn back to Him in some way. The Civil Rights Movement, the riots and all the things that were happening to us, like being hung on trees—He will afflict us in order to put us in a position to turn to Him, and I feel like that’s happening again now, and I gotta tap into it. —END

Left - Sweater and pants by LOEWE, shoes by MARTINE ROSE.

Right - Hat and jacket to WALES BONNER.