Stick with the Winners: F1 Miami

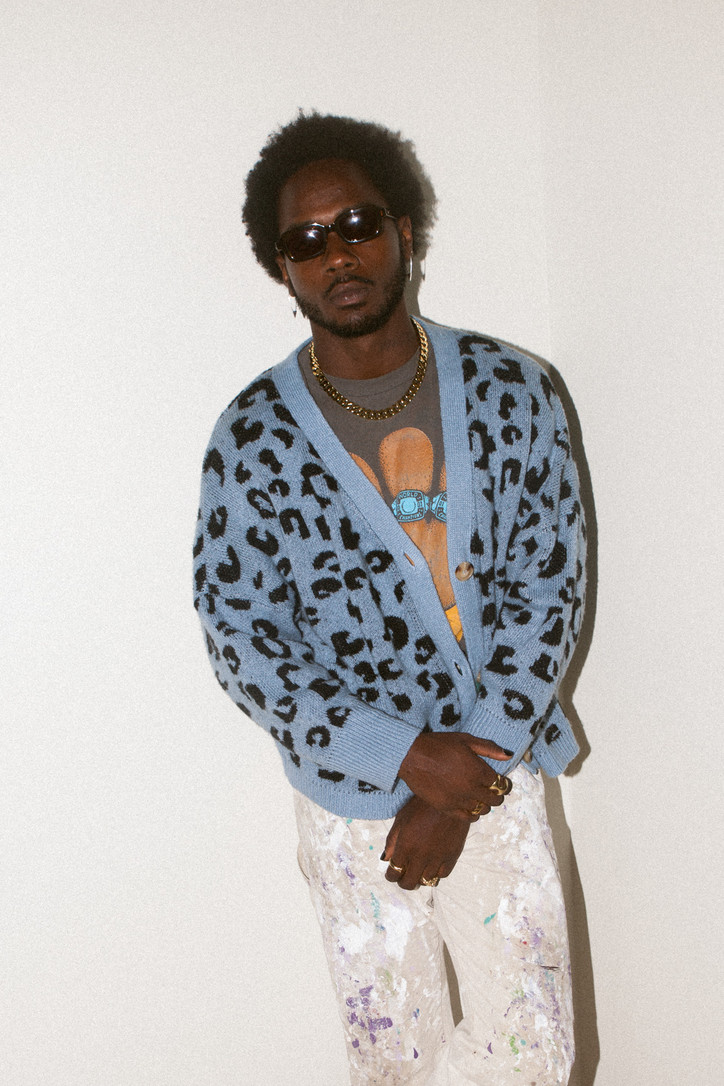

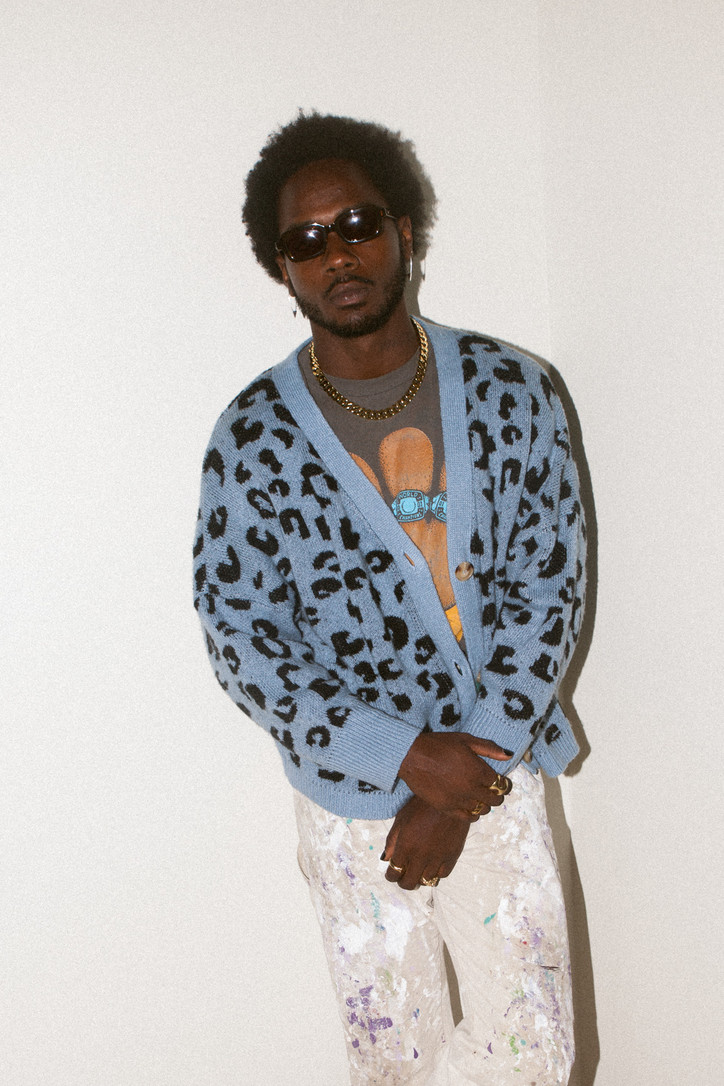

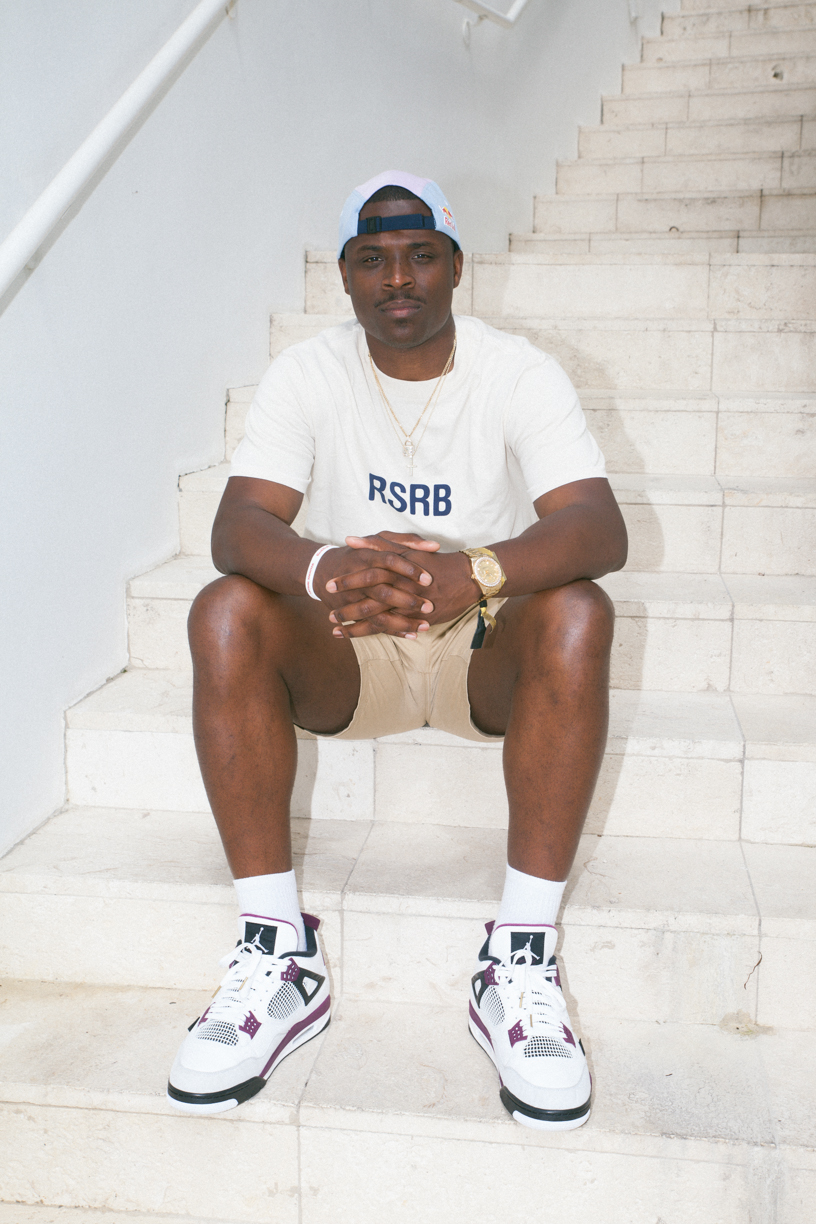

Chanel Tres before his performance at the Faena.

Stay informed on our latest news!

Chanel Tres before his performance at the Faena.

Noomi Rapace — I'm so excited to do this. I've been such a big fan of your work ever since I saw Downloading Nancy on a plane. I was completely destroyed. I watched it again straight away.

Johan Renck — That's funny. I just got an email from one of the producers. They're planning a restored re-release in LA. But same, I'm a huge fan of yours. You’re one of those Swedes who gets it. Always moving and shaking it all over the place in all sorts of ways. Relentless energy. You're like a Svengali; you bring people together, find connections, you know everybody on this planet, and you are a formidable actress.

Simon Rasmussen — Noomi, thank you so much for always being curious and wanting more and never settling for less. That energy is what we need.

NR — Before this call, I was thinking about the three of us. It’s crazy: one Dane and two Swedes who broke out and started something else. Your magazine is one of my favorites. It really digs into all my favorite art fields. I feel like a lot of things today slide into something where that becomes either too pleasing or too vulgar.

JR — I so agree with that. I used to just devour various publications and magazines, always in the world of fashion, culture, and music. It's amazing that you hold that banner up. I fucking miss the days of magazines when you’d go out once a month, buy a bunch, and spend the whole weekend reading, getting inspired and discovering shit. There's been a "death of publications" in a way that has forced almost all of them to become so ridiculously polished and policing and polite. I'm not interested in that at all.

Thank you. Sometimes young people approach me like, oh, Simon, I want to start a magazine, and I'm like, don't. It's not worth it. It's messed up [laughs]. It's a weird time for media. I used to buy at least five or six magazines a month, and that was how I got inspiration and knew what was going on. Honesty, in a sense, we don't need that anymore. It's like this weird thing where, yes, we go to magazines for photography, fashion, and culture, but it's so accessible now. We're caught up in our own speed of entertainment and media.

JR — I get it. What a magazine does is curate cultural output and write about it in depth. My sense is that we don't need them as much because many of the things that are covered in these types of publications are slowly dying. Music is no longer as relevant a carrier of youth culture, same with fashion and so on. Music is bigger now than ever, but it doesn't have that kick that it used to. It's not like people are dressing like their idols or writing their lyrics on walls in the city or anything. The same with fashion. It's like expressing yourself is no longer about fashion to some extent, it's gone past that. There are no rules to break. You can wear whatever the fuck you want, nobody gives a shit.

NR — When you screened Spaceman for me in New York, I was running around doing all these bits and pieces. Then I finally got to sit for two hours in the screening room that you set up and I just got to be in your world for a solid chapter. Those moments when you sit down and read an article, dive into a book or watch a film, become diamonds in me today, more than ever. I've watched your film three times now because it's such a beautiful piece. It feels like it's rooted in a love for traditional cinematic filmmaking, but also is a flirtation with the now. It doesn't rest, it never gets boring. It's not slow cinema, but it kind of feels like slow cinema.

Print magazines remind me of movies. Slow although they might not always be. Not to be nostalgic, but there’s that depth to it that grounds you and you can't help but get emotionally involved.

JR — To me, you're a product of the time you're working in. Any kind of expression you do is always going to be a bit of a protest. I'm very much an antagonist. I don’t follow formulas. If everybody's doing that, I'm doing this. In these days of being overfed with very trite content, the film has gone down in quality so drastically over the past 10-15 years. If you watch a dumb comedy from 2001, you go, Fuck, this is a proper film. Then you watch a serious drama today and you go, What the fuck is this shit? Bad writing, bad directing, bad everything.

NR — Because it's rushed!

JR — It's rushed, but it's also done for the wrong reasons. To me, any art form is ultimately about making people feel things, not think things.

NR — And it's not about being liked either. When everything is done to get as many likes as possible and make the loudest noise, it's akin to shooting ourselves to death because there's just more and more noise and little room to hear. That's one of the strengths of your film; there's a simplicity to it.

JR — Even subconsciously as a creator, you tend to draw from things that are meaningful to you. It's funny that Spaceman and Constellation premiered on the same day. Both films deal with loneliness and fractured relationships. In Spaceman, somebody asked our guy, "Are you the loneliest guy in the universe?" And in Constellation, somebody says, "And right now, this woman is the loneliest person in the universe." You can't help thinking about the fact that there is this increased sense of loneliness in general terms; we're all becoming more and more lonely. The reason both Constellation and Spaceman happened is that there's an identification with these types of sentiments and feelings.

NR — Also, who are we today? Many people don't take the time to reflect and actually look at their lives. The movies are the perfect setup for introspection. Am I living my life?

JR — But in Constellation, there's this profound moment that was much bigger than it's perceived. There's a scene where you're talking to yourself, saying something like, "It's weird how much pleasure I find in hearing when I can't hear any other voices. I'm so happy to just hear my own fucking voice." Do you remember that line?

NR — Yes. Something like talking to myself gives me a sense of comfort, even if it's just my own voice. It's like, "My voice makes me human. It lets me know that I'm still here."

JR — But I wouldn't be surprised if someone did a global poll and found that people are talking to themselves more than they were 15 to 20 years ago. I find myself talking to myself when I'm roaming around.

NR — Simon, do you talk to yourself?

I talk to Siri!

NR — [Laughs] With life it's like, what is success? Like an astronaut that worked so hard for a mission, prepping for years to go up there, and then they're up there. Then it's like, now what? I'm here, and I'm not sharing it with anyone. You can be the most successful star in any kind of field and still find yourself lonely.

JR — You can't share it with anyone. Every time you're away shooting something and you come home, part of you is bubbling with so many new experiences and things you learned, but it's impossible to share that. You know what I mean?

I love that part of what you shared, Noomi. It's a human condition where we're searching for this thing. Being able to make art is beautiful, but it also comes from a place of searching for this thing already there. I don't have to reach the outer galaxies to find out that the one I love was always right next to me. It's the same thing when we're creating things, existentially, it’s not going to make a difference.

JR — I agree with that.

NR — Hanus [in Spaceman] is almost like a modern Yoda because he speaks with thousands of years of wisdom, but almost with a childish belief in something more. Like Alice, in Constellation. Alice and Hanus are the two truth-tellers in our two different projects, reflecting without judgment, being a sobering and innocent eye on something that has gone seriously wrong.

JR — I agree, but the fact is that we're all only here for one reason, and we’ve been programmed for it. To consume. We've been duped into believing that when we're having a great dinner with friends at a restaurant, we're having a meaningful meeting. But what we're really doing is overpaying for a bunch of fucking food — spending money. Over the last 200 years, we've slowly turned into nothing but consumers. There are millions of micro actions in daily life that, if you flip over, you'll see like, yeah, man, it's part of the consumer pattern. That's all it is.

Unfortunately I think it’s just going to get worse. We've only been around for about 50,000 years compared to the 4 billion years of Earth's existence. There's a high chance that we won't exist in 50 years based on our hysterical consumption, and ideological ideas of “progress” and “success”. I sound like some old boomer communist now, but it's just facts.

You don't believe in a second chance? Or a resurrection?

JR — Of humanity? No, I don't. I believe in nature, and we have turned our back on the idea of evolutionary thoughts and on being a species interacting with our environment. I mean, a second chance, we're already past that.

NR — But what is the second chance? I mean, I've gotten so many second chances in life.

JR — Yeah, as an individual, but not as a species.

NR — So if we look at ourselves and the beauty of art… when an artist I love drops an album, I'm like, Whoa, I'm going to stay in this universe. I listen on Spotify, read the lyrics, and I stay there. Sometimes I feel like I've had multiple life chapters, like I can have a second chance and a third. We had this conversation after Lamb in New York. When something is new, I look at myself with fresh eyes. The beauty of life is that it’s constantly changing. Even dark and horrible things can lead you to something.

JR — I don't disagree with any of that on a personal level. But it's about the fact that there's nothing in the bigger scheme that drives towards the betterment of humanity. There are financial interests only. Everybody just wants more, faster, cheaper. I'm sounding bitter, but it's just a stern and factual look on things. All we can do is keep on doing the best we can, find beauty where we can, and find love where we can.

I agree. I'm seeing, feeling, and hearing a shift amongst the generation born after 2000. A punk resistance almost. Now punk is being offline, not having an Instagram account, not giving a fuck about likes.

NR — Totally. I had a conversation with my son about that actually, who's 20. He hates Instagram and he's totally anti-celebrities. That is punk, as you say. There's a lot of hope in that.

JR — I mean, punk in all honor, I love. I grew up in the seventies. I had my own fucking punk band. I would still die on the hill for the Clash.

NR — What was the band called?

JR — I don't even fucking remember, I was 14. But punk unfortunately hasn't had a lasting impact beyond pop culture circles. The ‘70s punk scene didn't change the machinations of the bigger scheme. It didn't change governments, it didn't change laws. It's just a reaction or antithesis to cultural movements. But, punk will always exist in some way or another, and I love it.

I know for sure that a lot of kids have a completely different outlook on being online or offline, which is great. These kids are probably going to be smarter than others and they're probably going to grow up and become something good. But ultimately, it doesn't fucking matter because the bigger machine is going to quench all those kinds of things in order for everybody to get more and cheaper stuff.

NR — But all the responses to Spaceman and Constellation — the strong reactions and the love — suggests that these projects hit some kind of sweet spot in people because they question identity and reflect on life without cynicism. It's interesting because a lot of things are cynical today and still work really well.

Yet, there' are previous generations who have already gone through the circle of cynicism, dealing with mental health issues when it was taboo to say, 'I'm really fucking unhappy.” I feel like it's less taboo to say that now. And as you say Simon, there's this emerging subculture of youth that refuses to be online.

JR — I also see that in artistic expressions, we've built a lot of cynicism over the last couple of years. Even films like Barbie or Poor Things have a cynical aspect to them. I like that there's a movement against that because I'm not so interested in cynicism, and like you say, both Spaceman and Constellation are completely devoid of it.

NR — I feel that your films, whether Downloading Nancy or Chernobyl or Spaceman, have a love for humans that shines through, even in the darkest scenes or moments. I walk away from watching and engaging with your art feeling less lonely. The Chernobyl [disaster] is such a horrible event in human history, yet your masterpiece carries the simple message that we're just humans at the end of the day.

JR — Despite my somewhat gloomy view of the world, I wouldn’t say I’m cynical at all. I'm a humanist. I believe in love and beauty. As an artist, I'm just trying to express myself and be understood. It's a continuous process — sometimes people get it, sometimes they don't. But that's what we're all doing, trying to connect through our expressions. I believe in the human condition, in love, and for the most part, see the good in people.

But we have to remember how weirdly primitive we are. We're a very new species. If it takes an ant 200 million years to learn to live in a colony, just imagine. It's ridiculous. We're still bickering with neighbors, still trying to figure shit out. It's fascinating to think of how we're figuring it out as we go, rather than instinctively or the normal sort of means of any other species figuring things out in a balanced way.

To me, the beauty of life there, in exploring the unknown.

JR — Parenting is a prime example of that. You spend years in school learning about the Battle of Hastings and whatnot, and then suddenly you come home with a baby from the hospital, and it's like, “I don't know one fucking thing about what I'm supposed to do now.” The journey of learning how to deal with it is beautiful.

For me, it's finding out that everything is really simple. Like what Jakub finds out in Spaceman when he's like, “Fuck, it was there all along.” It's the same with parenting and anything else. We don't need all these things. Just be, and you'll be fine.

JR — There's something very simple and sort of pure with that outlook. It is what it is, just be in the now.

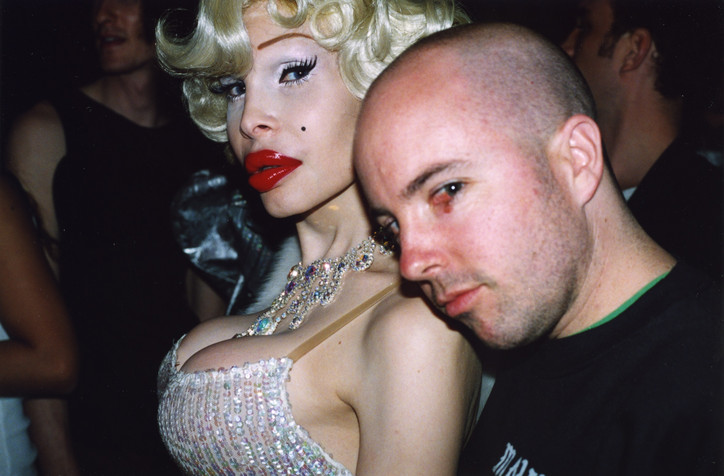

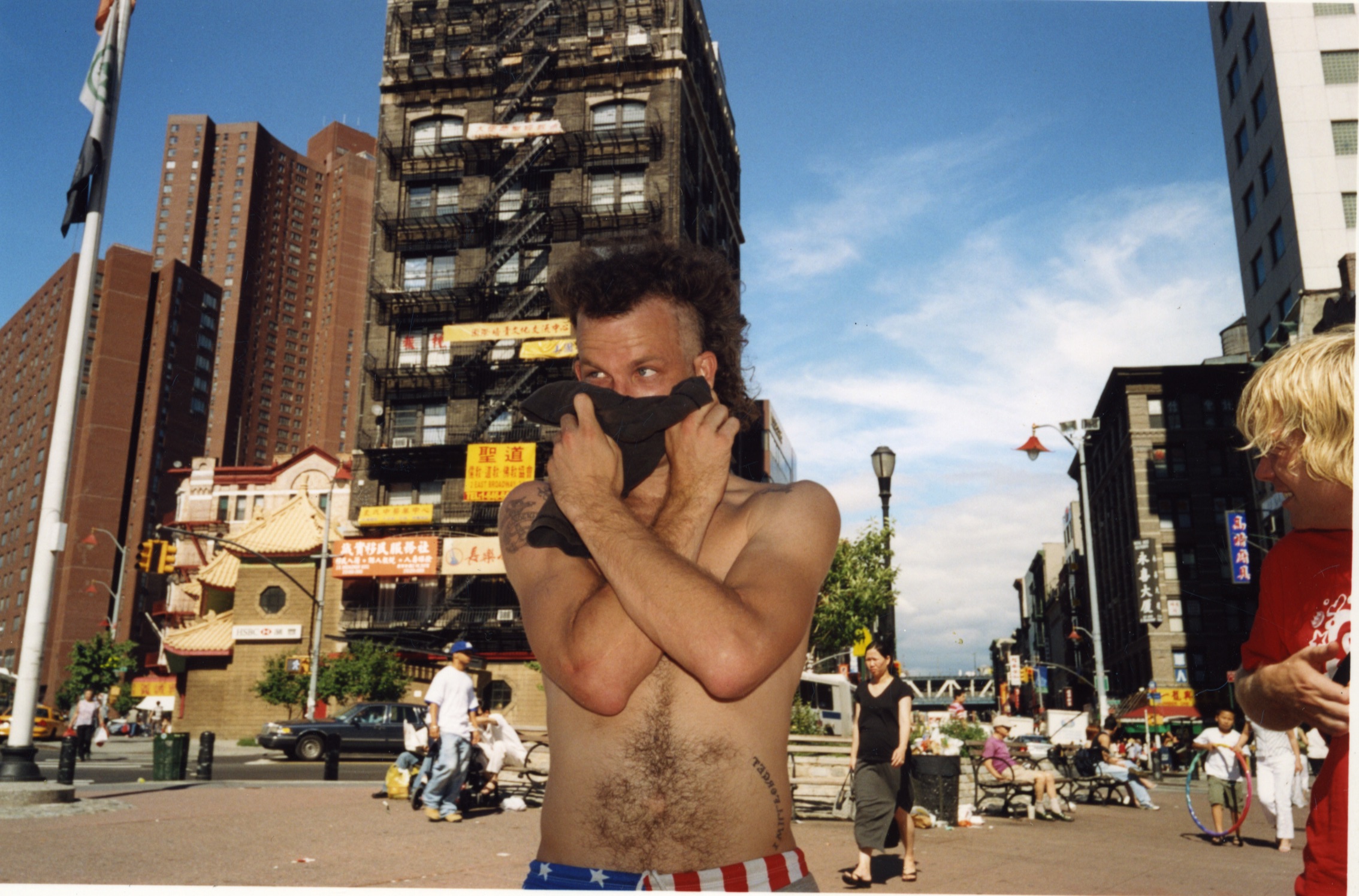

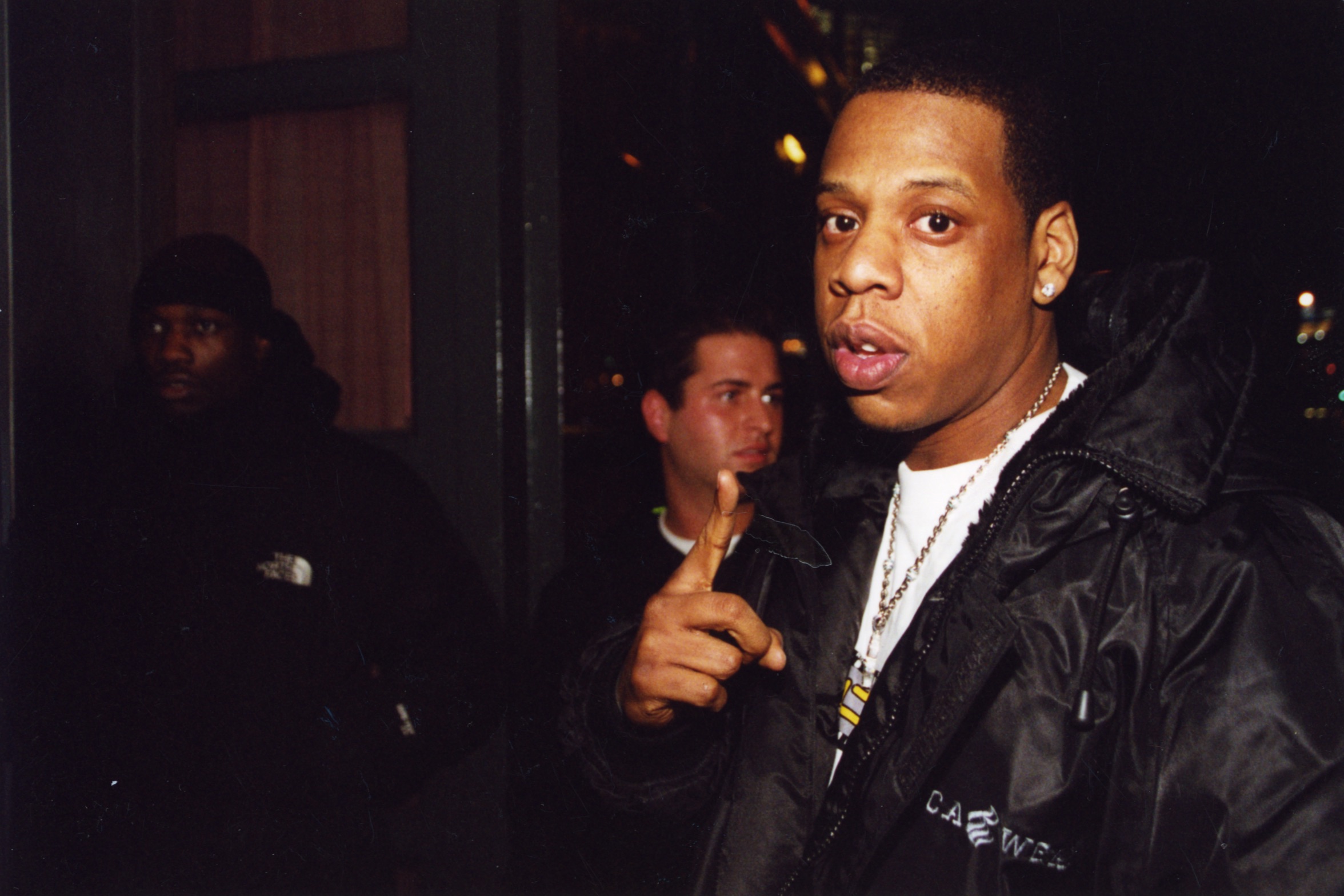

Amanda Lepore

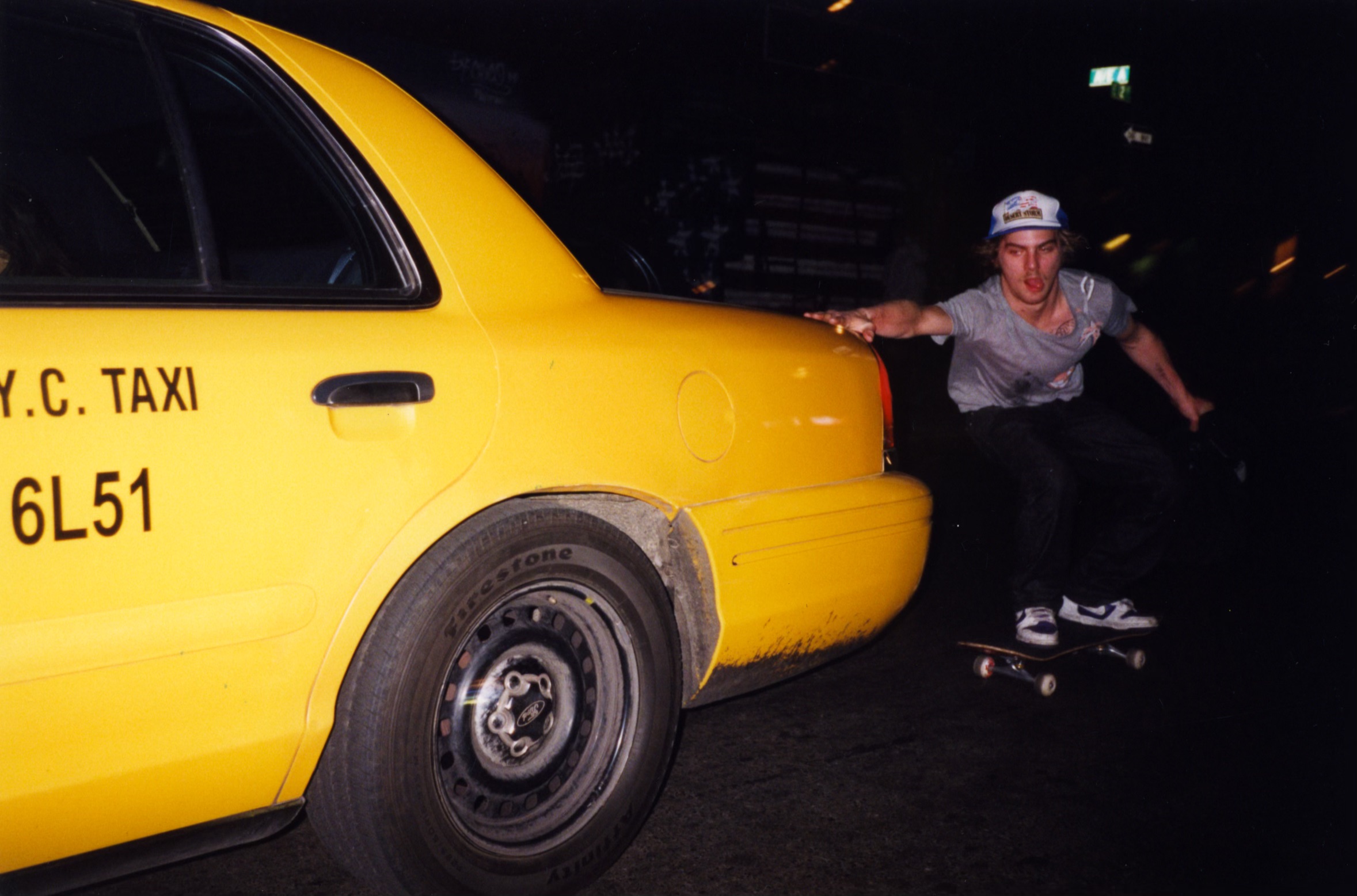

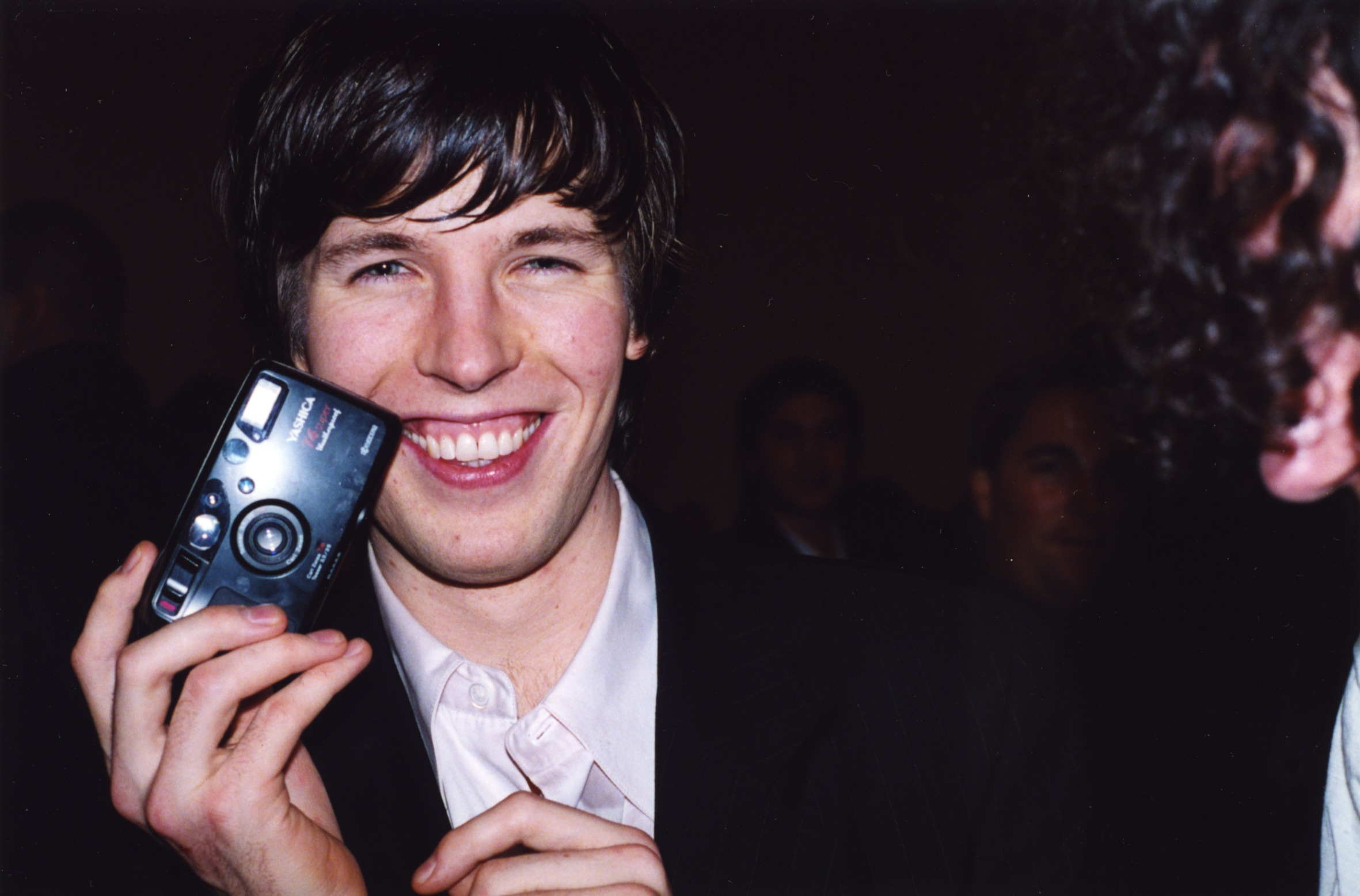

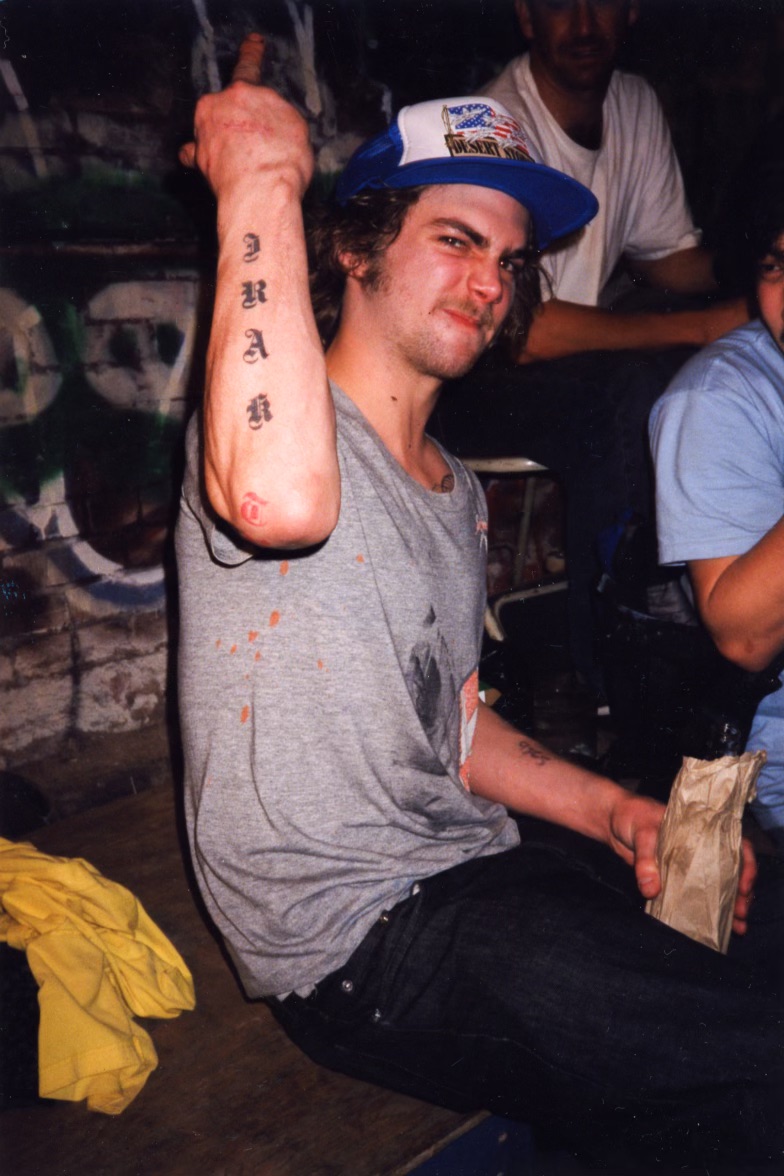

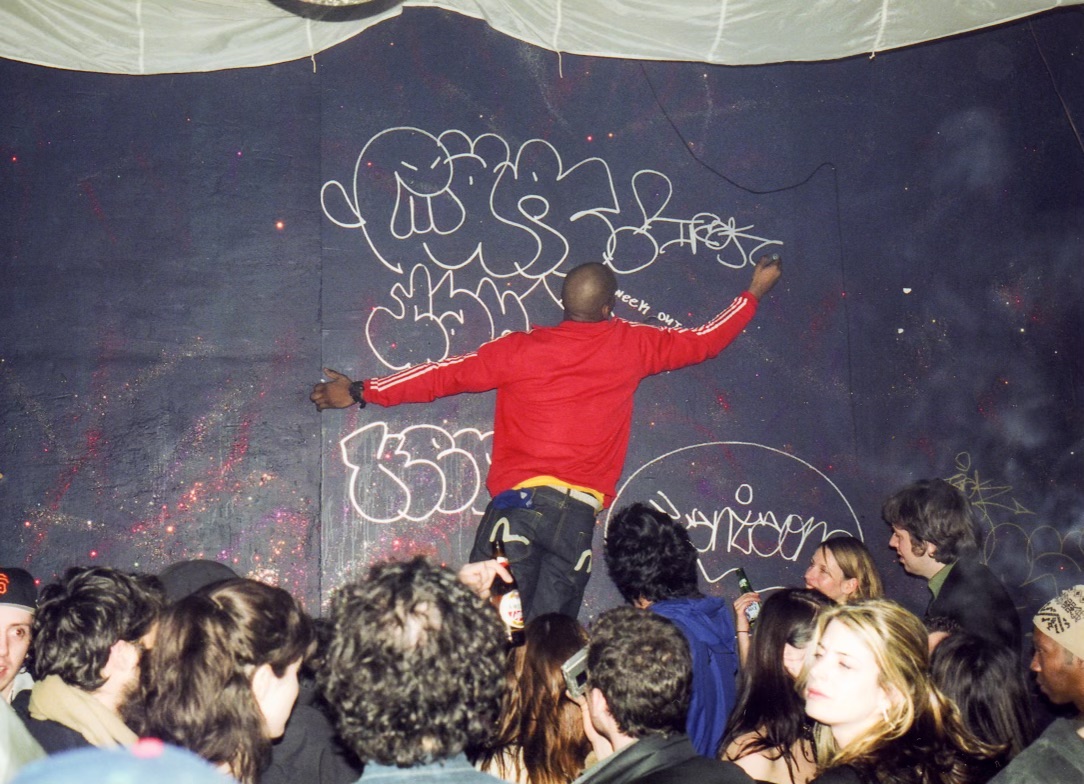

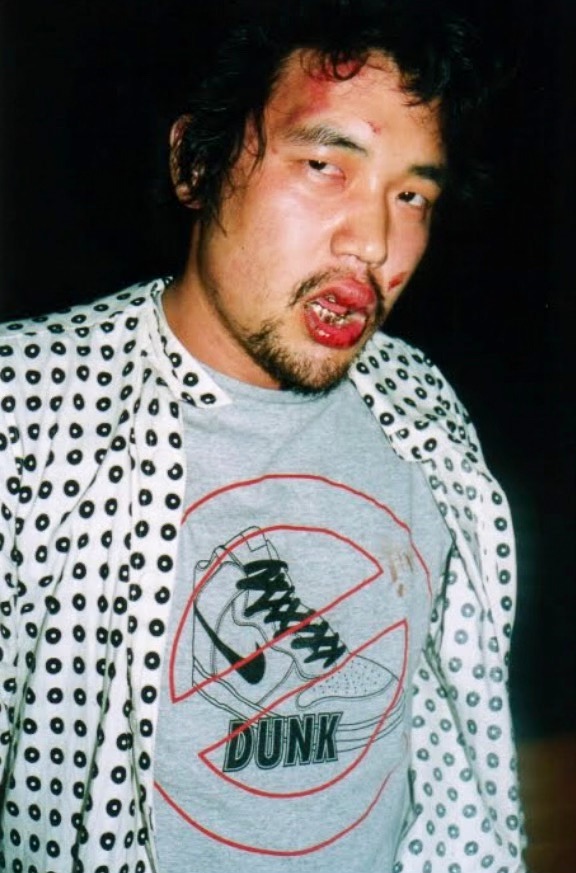

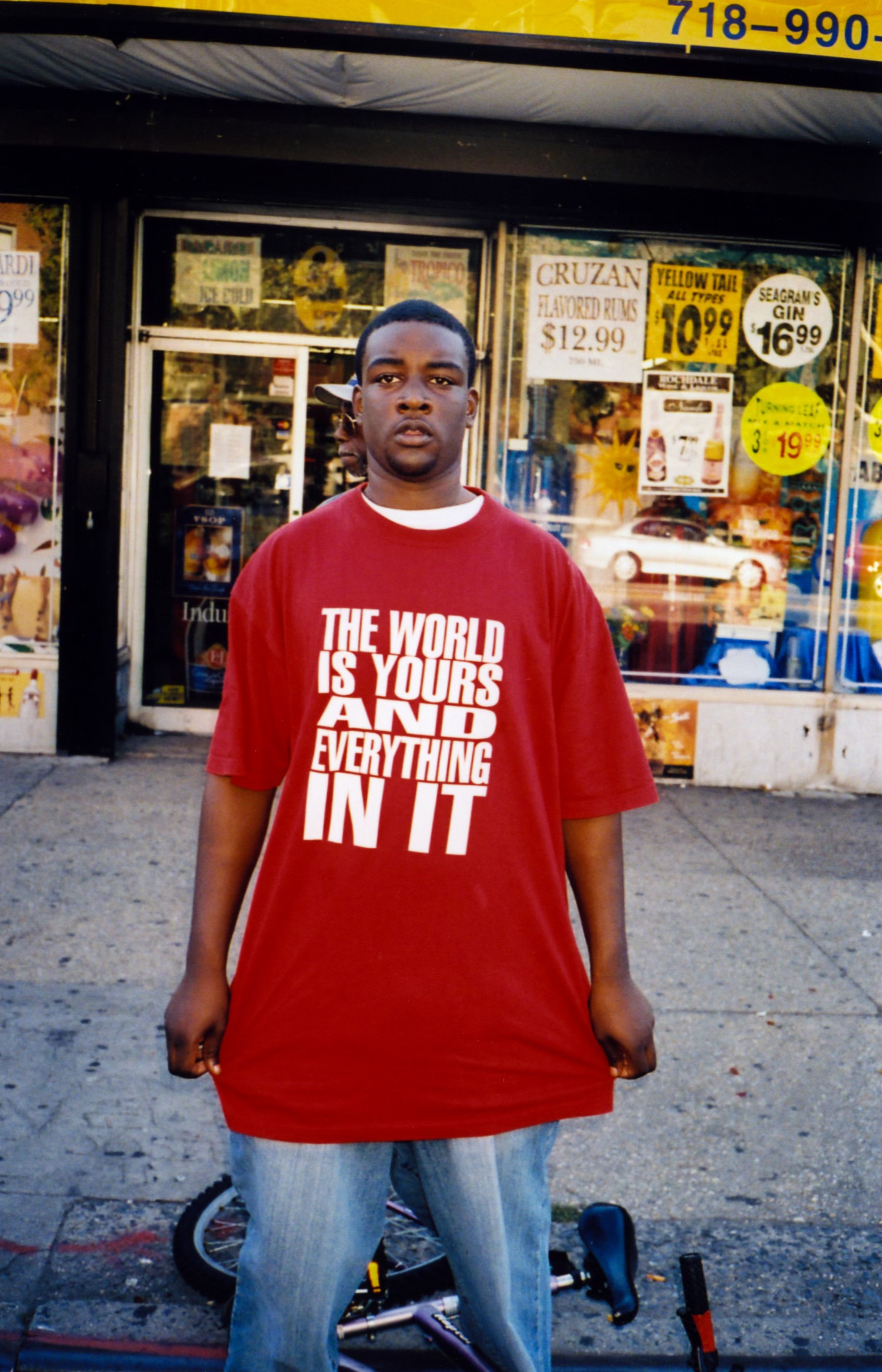

Beyond the exhibition, Alain’s book of the same name, available May 1st, acts as a time capsule, a snapshot of what he and his friends were getting into back then — figuring their lives out, meeting people, making memories and now, reminiscing on what was. Today, walking through Dimes Square where his and his wife’s restaurant, Bacaro, has become a premiere meeting hub for the neighborhood's youth, Alain recognizes that while “it’s such a different world,” the kids are still the same.

“Young people are young people, man. It’s different being older and not really understanding what’s going on. I don’t fully feel like I’m part of it in the same way… but I love it and it seems the same, but one thing I see is it’s more colorful, it’s animated, and everything seems kind of to an extreme that I really love.”

When Bacaro first opened in 2007, there was no Dimes Square. He likens the emergence of the neighborhood to “the beginning of Williamsburg when that kind of popped off and all of a sudden, if you went down Bedford, it was just young people everywhere and everybody was dressing outrageous.” Back then, congregating in Bedford symbolized a communal rejection of Manhattan. What Levitt witnesses in Dimes, a neighborhood that’s become a bit polarizing amongst New Yorkers, is “more or less the same thing” — though the object of its rejection seems yet to be defined.

Perhaps it’s more of an acceptance — of indulgence, of being part of something, of embracing the past, keeping alive this idealized perception of NYC.

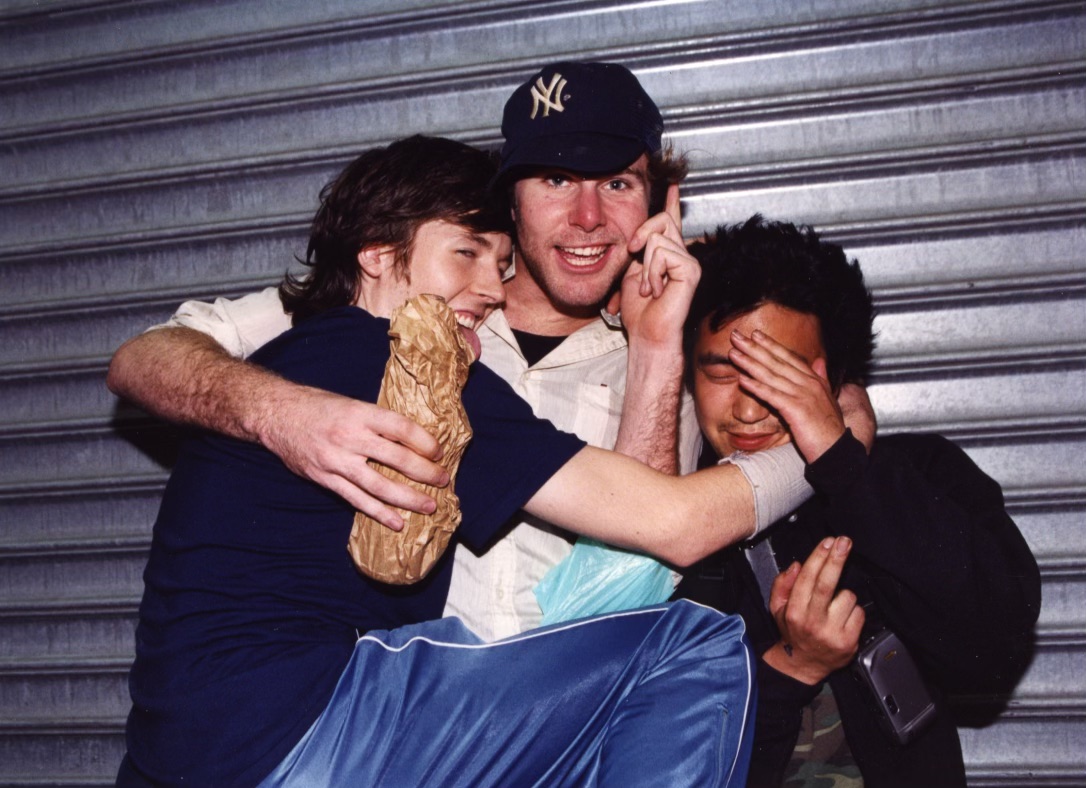

left to right - Ryan McGinley, Dan Colen, Kenji Ukigaya, Dash Snow

When Alain moved out here in the ‘90s, his older sister Danielle gave him a camera. At that time, he didn’t consider himself a photographer. He was just a younger brother emulating his older sister, who was shooting street photography and fashion parties for the Post. Alain recalls “showing up to Max Fish and being gently made fun of for his oversized paparazzi rig.” For his second job, Alain was working as a bar-back at The Cock and The Fat Cock (now known as The Hole), giving him “a front row seat to a wild NY that was quickly being choked out by Mayor Giuliani.”

On one of his first nights, he was assigned to the back room at The Cock, where patrons would do whatever drunk people do in the dark. As a kid “brand new to New York” flashing a light on people, he realized that suddenly, his life was completely different. And it was exciting. “I made more money than I could have ever imagined. I was working minimum wage jobs coming from LA, at movie theaters and all this other shit. In NY, I was able to live off two days a week which gave me room to do everything.”

Eventually, Alain started shooting for Nylon, PAPER, V Magazine, and other publications on his days off. Though they didn’t fully feel like a part of that world, he and his friends (skaters, graffiti artists, ravers) disrupted the fabric of the fashion scene. Reminiscing on some of those moments, he tells us, “Our group would show up at the fashion parties and make our presence known, even though they probably didn’t think we belonged there, that maybe we hadn’t earned it yet.”

left to right - Ryan McGinley, Chloë Sevigny

Then, Alain found his community on the Lower East Side, “Alife by day, Max Fish at night,” and “after starting a bi-weekly party, with Spencer Sweeny, at The Hole," planted his seed in the downtown scene. The world that Levitt found himself navigating in his early years in New York City wasn’t new, it was itself a continuation of the pseudo-renaissance that emerged downtown in the ‘60s and again in the 70s and again in the subsequent decades. “It’s almost like a 10-year cycle and one good thing about New York is that it lets you be young a little longer. We were coming out here thinking about the CBGB’s era.”

And when looking through Alain’s photos, while humming with an inherent sense of nostalgia, it feels as if these images could’ve been taken yesterday. Skateboarding, bands playing one-off shows in dingy music venues, gallery openings that pour out onto the block, it’s all still here, just slightly different. While the internet has made us more connected, and distractions more frequent, much of what was, still is. And for Alain, there’s an innate resilience to this culture of “youth”, a culture somehow driven by a shared dysfunction. “Living in New York is so hard, rents are high, the weather is hard. It can be amazing but you have to put up with all this other bullshit to get the best out of it. You have to be willing to suffer. The people that I knew and the people that I connected to and was around — there was always a certain amount of fucked-up-ness we all shared.”

left to right, Dash Snow, Kunle Martins (Earsnot)

Whether seeking self-discovery in New York City, escaping a toxic family, or generally curious to explore the city’s burgeoning underbelly, people here find their own, often forming surrogate families along the way. Levitt’s book, and the photographs on display at WHAAM! exemplify that family isn’t always clean-cut and you might bond with a person you’d least expect to: on the train, at a bar, laying on the grass at Seward Park, skating at Tompkins, or having a plate of squid ink pasta at Bacaro before heading to Le Dive for some overpriced house wine.

In the most ordinary moments, the greatest ideas and connections can spring to life and this was true even then. “I imagine creativity drives a lot of this,” Levitt says. “There’s a thread that we saw and maybe even idealized New York City to be.” It’s a thread that this generation hasn’t seemed to let go of: “I feel like my book shows our moment of coming into ourselves and now the kids today are doing it themselves. In 20 years, there’ll be a record of their time that the next group of kids will be looking at. It might not be the same, but the roots are.”

From Tim Barber, a former photo editor at Vice who edited the book, to Jesse Pearson, former EIC at Vice, Su Barber (Tim’s sister), Mike Piscitelli from Fucking Awesome and skateboarder Jason Dill, everyone involved in the book “from the editors down to the publisher was there in our circle, and pretty much all in the book too.” To Alain, everyone in the book was of equal significance, whether downtown sweetheart and bigtime starlet Chloe Sevigny or Marc Razo of Max Fish, “a loving, wonderful person who’s been in the downtown scene forever.”

“Some of those people have definitely become legendary, which is awesome,” says Levitt. “But with them, it’s like me, I felt special to be there. I wanted to be with these people and we all had all of these lofty ideas of ourselves that were shattered over time. I think it’s good to break through those delusions of grandeur and get a real sense of what the world is. But at that moment, it was pure. We all thought we were special.” And maybe we still do.

NYC 2000-2005 is on view April 18 - May 25, 2024 at WHAAM! at 15 Elizabeth St # 113, New York, NY 10013.

After guests settled into their seats, the night’s honorees Patricia Arquette and Megan Thee Stallion lauded the organization’s work and the manifold ways it has affected their lives for the better. Overcome with emotion, Megan accepted the Catalyst for Change Award, in recognition of her choice to advocate for bodily freedom and sexual liberation through her platform, and inimitable tracks like Plan B.

“Planned Parenthood has been a leader while abortion rights are under attack. Y’all are the true heroes,” Megan shared in her acceptance speech. “I’ve always known that I have a bigger purpose than just being a musician, and to speak up when people need our help.”

The second of its kind, the gala celebrates the work of the organization while honoring particularly devoted advocates, hosting an auction to raise funds for annual operating costs, and rounding out with an afterparty featuring host Patia of Patia’s Fantasy World, and DJs including Boston Chery and river moon.

“They’ve been there for me and a lot of my friends, especially when I first came to this country and needed healthcare,” Moon said. When the lights went down and guests trickled out onto the street, the event’s urgent appeal was in clear and energizing focus, primed for a productive year ahead.