Stored

The series produces an eerie prediction for what's to come. "A day in summer 2020. Social isolation has become normal. The new disease is called hypochondria," says Roché.

Check out the rest of the series below.

Stay informed on our latest news!

The series produces an eerie prediction for what's to come. "A day in summer 2020. Social isolation has become normal. The new disease is called hypochondria," says Roché.

Check out the rest of the series below.

Read our discussion with curator Carla Fernández below, where the artists discuss control, anonymity, and the necessary risks that should be present in art.

Juan Antonio Olivares— I was really happy to meet you because we both know Carla but our paths had never crossed. I always sensed a mischievous humor in your work, so I was glad to put a face to it.

Kaspar Müller— I recognized your face even though it was our first in-person meeting. I’d seen images of you with short hair and a broken leg.

JAO— Oh yeah...

KM— After that, we didn’t communicate much until Carla connected us for the show.

Carla Fernández— It was an easy decision for me since I’m close to both of you. For the first show in New York, it made sense to exhibit a conversation between two artists with some momentum. Juan and Kaspar share a sensibility despite having different perspectives, which is an interesting entry point for me.

Often, Latin American art is shown with a focus on folklore or colonialist mockery. Juan studied at The Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, proving you don’t need folkloric associations as a Latin American artist. Conversely, Kaspar’s work is very folkloric, creating interesting tensions and contradictions. The netting of Kaspar’s Catapult was made by an artisan, blending these ideas without categorizing what Latin America is. Hopefully, it moves towards a global discourse.

Devan Díaz— Juan, in the show’s press release, you mention a conceptual image being an oxymoron. Did the AI text-to-image generator make a conceptual image possible?

JAO— 'Conceptual' is a loosely used term today, often meaning “looking smart.” I'm inspired by 1950s and 1960s conceptual artists who questioned art’s materiality. Many of them were performers and theoreticians before making objects.

A classic conceptual image is Joseph Kosuth’s "One and Three Chairs," where you have the definition of what a chair is, the image of the chair, and then there’s the physical chair. It represents the essence of a conceptual image because it involves three inextricable parts. The AI image generator I worked with takes a text prompt and turns it into an image by analyzing the prompt against a large database of existing images the software has learned from—much like a human brain does but with quicker and generally more awkward results.

KM— The machine’s faceless theme, produced from input, interested me when I created these figures now exhibited as paintings. They started as reference pictures for the straw man I exhibited at Basel. My kids took pictures of me posing in our living room, and using an Apple AI tool, I isolated these figures. Suddenly, I had emoticons of myself without my surroundings. Completely unrecognizable as me. This byproduct became part of my straw man conceptualization.

JAO— I love knowing that. I didn’t realize how you isolated the figures. Our awareness of the readymade connects our work even more. The readymade is a traditional medium at this point, it’s over 100 years old. Isolating something by clicking on it, something even a kid could do, has a ready-made aspect.

KM— Most people discover it accidentally.

JAO— There’s anonymity in your images. I wanted to release my agency as an image maker by using an image generator because there’s freedom in anonymity.

KM— In the images, when I put my hat over my head, the figure becomes faceless. The audience can’t tell who it is and I couldn’t see either. Pointing into the void, I was in darkness, able to point towards nothingness with more determination.

The circumstances of these images make them highly ambiguous. I gave away control, not seeing what I was doing, and embraced the digital realm's freedom. These images weren’t the final product, so there was no pressure. I like recycling or reusing byproducts in the process.

DD— How are these images affected by the objects in the room?

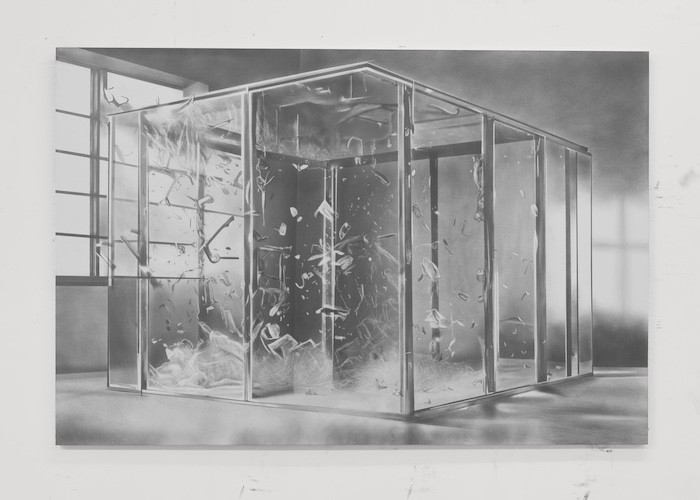

CF— AI, like emoticons, are digital tools. If you think about what will remain when we’re gone, like the sculptures, it creates tension with the images. Language and technology change constantly, and eventually everything becomes obsolete. Sculptures bring realism to the digital conversation. Two vectors exist—the horizontal digital realm and the vertical heaviness of catapults, glass, and metal.

JAO— In an early conversation about the catapult with Kaspar, I felt a welcomed risk factor. We discussed whether it should be on or off, its destructive capability. The ball and chain I made for this show is also functionally restrictive.

CF— Medieval surveillance restrained bodies, and now emojis constrain identities. Both forms of control.

KM— Creating this catapult, breaking it down to its simple function of destroying, involves absurdity. Wine, a Christian symbol with economic loss when spilled, is controlled by an algorithm. I programmed the catapult to go off unpredictably, known only to the person controlling the code.

JAO— Kaspar’s images, which I found humorous, seemed like positions of punishment. The obscured, hooded figure felt like bondage, which felt unexpected from you.

KM— We also talked about financial domination, a popular topic for artists.

JAO— In today’s financial climate, there’s precariousness alongside a pretense of stability. Exploring financial domination’s humiliation, similar to art’s unreciprocated transaction, was interesting. Art gives itself to the viewer with abandon.

DD— Is there humiliation in showing art to an audience, or is that the wrong word for public exhibition?

KM— I’m not bothered by it. I like giving it away, relinquishing control. Artists invest energy and sensitivity in their work, and giving it away means losing control. It’s a dynamic we can’t escape, but my goal has never been to remain unharmed.

JAO— The risk aspect is present in the show. I was expressing frustration with what I felt was a very tame New York art world. It feels like there’s no risk because people are afraid of things not selling. I don’t think either of us were trying to shock or ruffle feathers but expressing the precariousness of this world.

The Panther is on view through June 8, 2024 at 49 Walker Street.

In the mid 2010s, the art world finally caught up with Nadin and he started showing paintings at commercial galleries again. Recent exhibitions have focused on what Nadin calls “painting from life,” gestural marks about memories of his days in the Catskills and his impressions of the community around him. For his debut exhibition at Off Paradise, a project space run by Paris-born curator Natacha Polaert, Nadin showcased The Distance from a Lemon to Murder, a series of paintings he made during the pandemic shelter-in-place, situated somewhere between the real and the imaginary, about the threat of interpersonal domination lurking beneath the mundanity of the countryside. Nadin’s current exhibition at Off Paradise, The Invisible World, explores the unbridgeable separation between seeing and remembering, leading to incredibly moving moments.

Shall we start with the elephant in the room? You stopped exhibiting paintings formally for many years. What sparked your interest in returning to exhibiting painting in a commercial context?

I stopped exhibiting paintings because the painting that I was doing from the 1990s onwards was outside of the conventions of what we think of as painting, traditionally understood to be the intention of making marks. What interested me was the unintentional mark and resonance of activity, which were areas of exploration that really inform my painting activities. The more recent work I am doing really incorporates all those possibilities and there isn’t anything that’s by design or by necessity excluded from the possibility of mark making. When Natacha invited me to do a show, I agreed to showcase these possibilities.

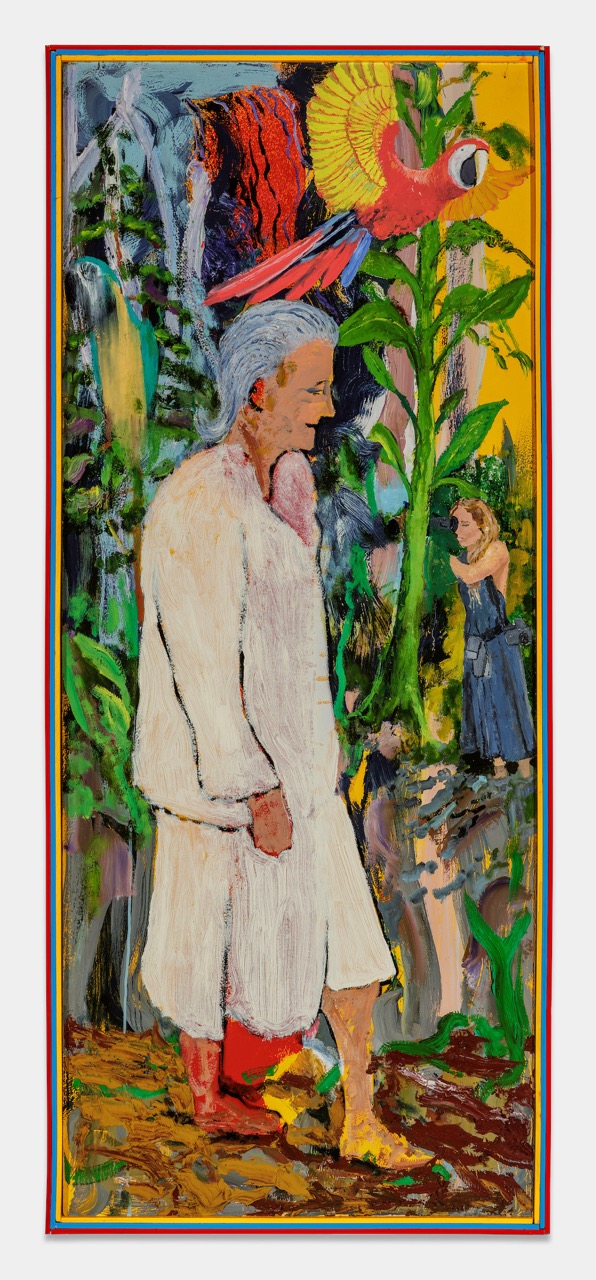

Adam Installing Utilities in the Garden of Eden Under the Devil’s Fire, 2023

How do your paintings fall outside of the traditional trajectory of painting making or mark making?

Curiously, over the years that I’ve been working, I realized that you can’t really judge what a painting is purely by what it looks like. You can have very unconventional paintings that are actually within the convention of painting. And you can have things that appear to be in a convention of practicality but are quite radical. You can’t always tell. It’s interesting to find out an approach that enables me to understand those differentiations. With those first mark paintings, it was unintentional, and there were no conventions. I didn’t know what was going to happen. When I look back at them, some of them seem quite beautiful, even though I had no intention of making a mark that would have any apparent meaning. Thus, I became interested in if meaning can reside in something that’s entirely unintentional, or if one has to intend to describe something that gives meaning.

And you were showing them in very unconventional settings or places.

I stopped exhibiting my paintings around 1993. I didn’t really have an agenda, I just wanted to explore different things. I began farming and became very interested in beekeeping. A few years later, I went down to Cuba as the US representative to the South American Beekeeping Conference. At the conference, I met a number of artists and curators who share similar ideas about the way agriculture could inform artistic practice. There was no market for contemporary art in Cuba, even though there’s a tremendous cultural heritage. They valued art in a very different way, for its spiritual meaning.

Through a friend working at the Wilfredo Lam Center, I met Hector, a beekeeper. I told Hector I hadn’t really shown anything in many years, because I didn’t really connect with the context. And he said, “Why don’t you do something down here?” That's how I started a painting show in Cuba. The show was met with enthusiasm and traveled around the island through the Center. And then a couple of years later, I did another show that traveled more extensively, it even went down to Cuenca, Equator. What’s wonderful about these shows is that the response was purely about what they meant, what it was, or what I was offering to them, since there’s no commercial engagement.

You made the paintings in this room while you were living in Catskills and they really pay attention to your surroundings and your memory of the environment and the people in your life? How does it feel to paint your life and your immediate circles?

At the end of the day, that's what I know and that’s how my time is spent. And I hope that I give the environment and the people that I represent the due respect, because the people that I see, know, and interact with are a subject so integrated within my life.

When you paint a landscape, they’re citing and constantly responding to so many important art-historical movements. Are you thinking about the history of art you’re a part of, or are you more just thinking about your immediate experiences or your biography when you paint?

It’s all part of the same thing. The experience that one has is going to manifest through movements of the hand and the arm. I approach a painting as if all those possibilities were already there. Sometimes it may have a resonance with some part of our history, and sometimes it may not. But I think if a painting is successful, it should not have subconsciousness. If the subconscious is present, it can interfere with the reading of the painting. I personally just paint hoping that I can give form to experience.

Three Self Portraits and a Ripening Lemon, 2023

Looking East, Seeing West, 2023

The paintings here have this poetic sensibility to them. You’re also a poet. I'm wondering if the two practices ever correlate with each other. Does your poetry nourish your painting, or vice versa?

Yes, they’re very closely related. I think evocation of the word is very close to the mark and the evocation of the mark. I can write poetry because I understand the poetic resonance of words, in the same way as I understand the poetic resonance of marks. The two inform each other without necessarily being bound up by the convention of the sentence, or the convention of the procedure of art making.

Let’s go back in history a little bit. You were a part of the downtown conceptual art collectives The Offices of Fend, Fitzgibbon, Holzer, Nadin, Prince & Winters. The collective itself was very interested in the circulation of image, information, and language and was producing very different works. The paintings in this room still feel connected to your earlier endeavor, in the sense that these paintings are very much thinking about the instability of memory and its circulation. Could you talk a little bit more about your interest in the porous boundary between self and the world?

It is really true that they are all part of the same inquiry, only the forms it takes are sometimes different. When I started painting when I was nine years old, one of the things that I like about the painted surface is that it can only have two functions. You can either look at it, or if it’s waterproof oil paint, you can use it to patch a roof or put it on the side of a chicken house. In other words, it’s indivisible. What we were doing with The Offices was not indivisible, because it could lead to other possibilities. I didn’t really know if our commitment to engage with the community could lead to some kind of long-term change. It’s an open question, as I’m not trained in those areas. However, I remain very interested in what social change and the method to achieve that might look like. My sense is that we are constantly engaging with perceptual and cognitive information from which one creates the will for transformation. If you want to create a different understanding of the world, you will create different procedures first.

What strikes me is that even though your paintings are so conceptually engaged with ideas of memory and information, it still feels very pleasant to look at them because there’s such a humor to them. What is your relationship to evoking emotions, especially humor, in your approach to paintings?

I think all of this must be present. Humor is such a necessity to create meaning. In a sense, it’s absurd to try to make sense of extremes with only our rational sense. Who would feel obliged to do it? In fact, some of the most profound, beautiful explorations of consciousness relies on humor. Nothing should be excluded from the beginning.

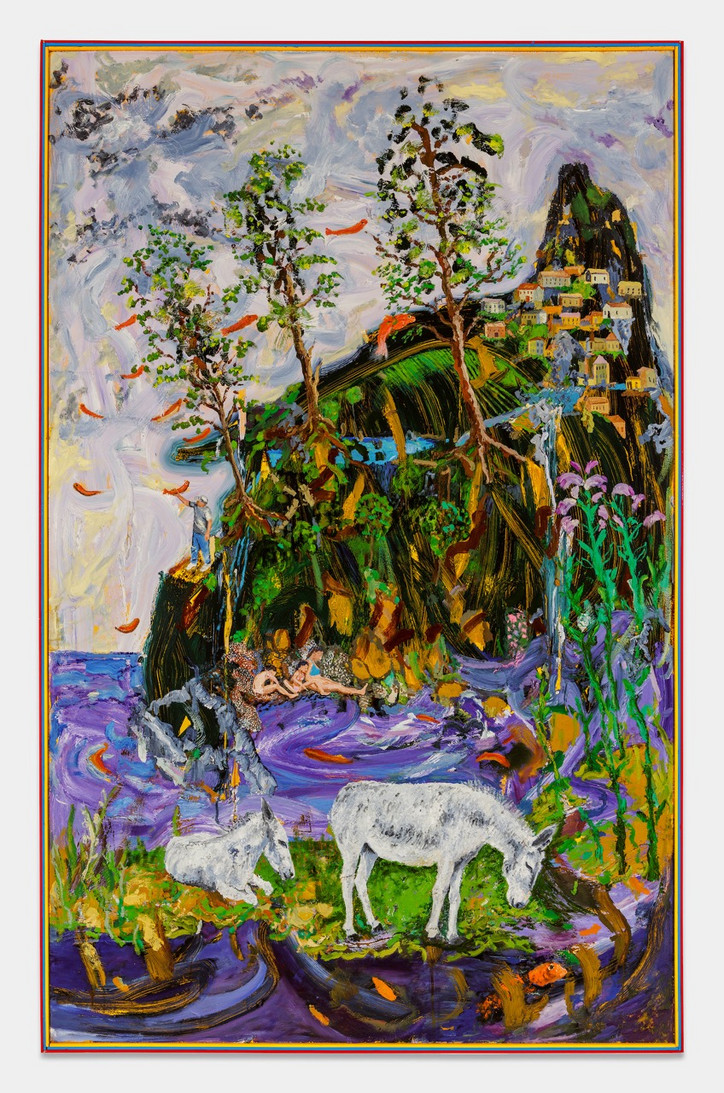

Sharkey’s Donkey Watching a Fish (A Migration of Golden Orfe), 2023

What are you looking forward to next?

I’m beginning to work on a new body painting. It often begins with a word or with a thought, a sense that there may be something that will light a little fire within the world. I don’t know if this little flame will develop into a conflagration. But if there is something, normally it takes about five years to be fully revealed.

Time feels so essential to your practice. You are often intentionally slowing down the temporality of experiencing your paintings.

Maybe in 15 or 20 years I can begin to see if I wish to paint in a certain different way. I can always begin again.

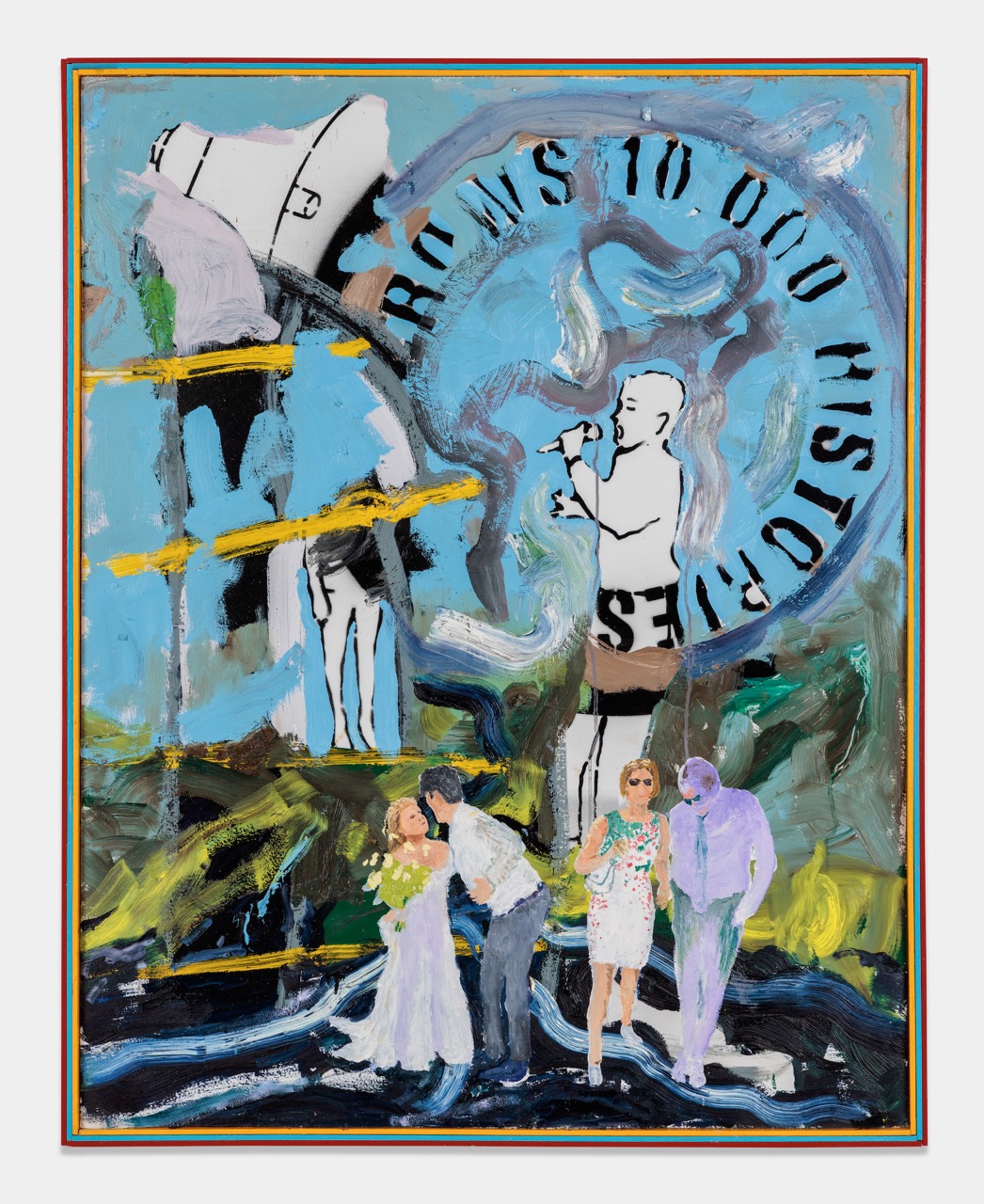

The Programmer, 2022.

The Secret Wedding of the Invisible Man, 2022.

I had the opportunity to interview Nishimura during her visit to New York. As we strolled through Fort Greene Park in Brooklyn, hearing about her journey leading up to her debut solo exhibition in New York, I couldn't help but think of the words of minimalist artist Carmen Herrera, who broke through at the age of 89, and Swedish artist Hilma af Klint, who refrained from exhibiting her work for 20 years after her death.

Yes, in their worlds, delays occur and time often lags.

"There is a saying, 'If you wait for the bus, the bus will come.', I say yes, I waited almost a century for the bus to come, and it came." — Carmen Herrera

Such delays were of no consequence. They each continued to pursue their paths in their own way.

And so Carmen Herrera waited for the bus, Hilma af Klint calculated the time difference, and Tamiko Nishimura kept on her journey.

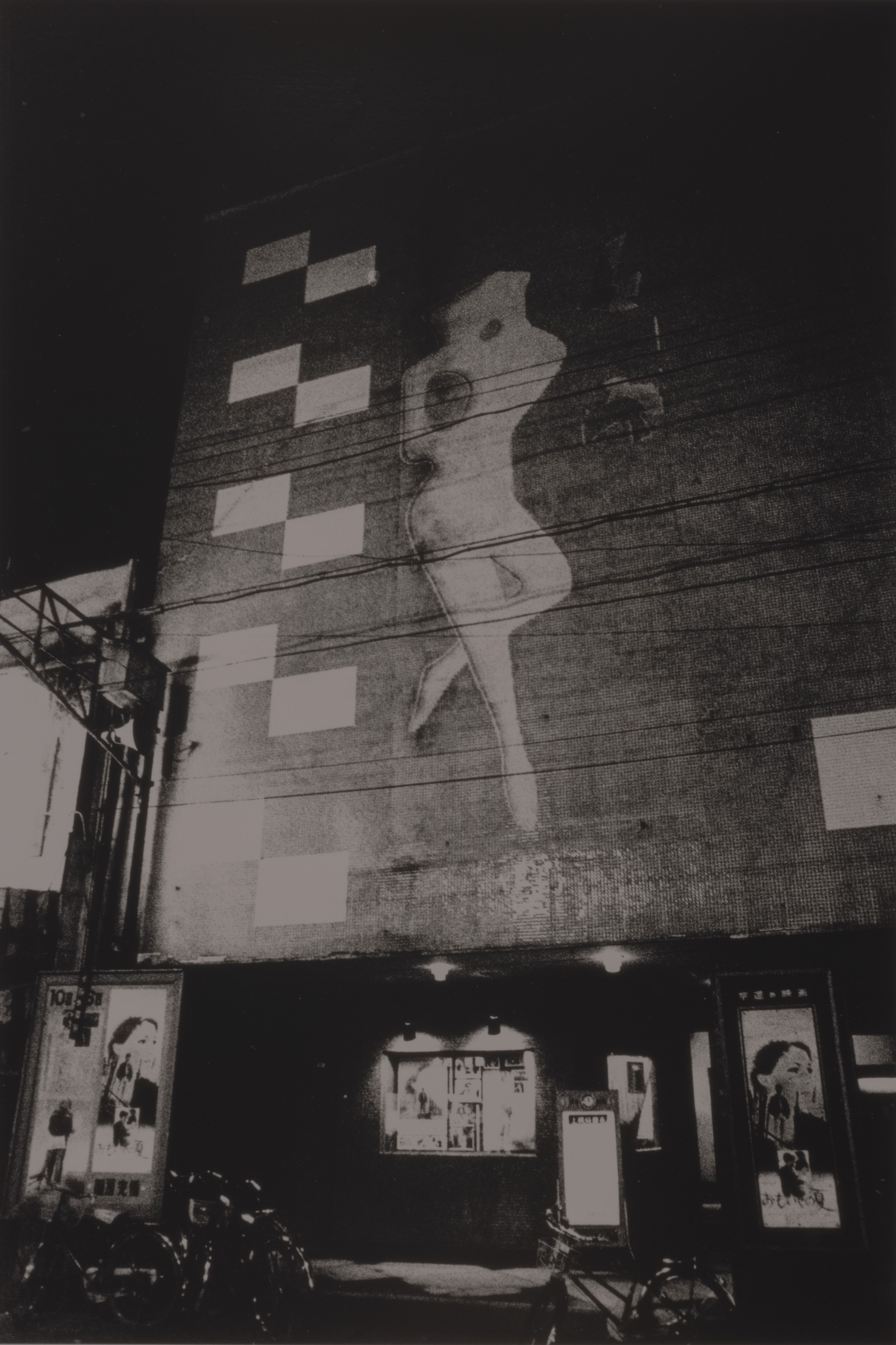

Eternal Chase (2012)

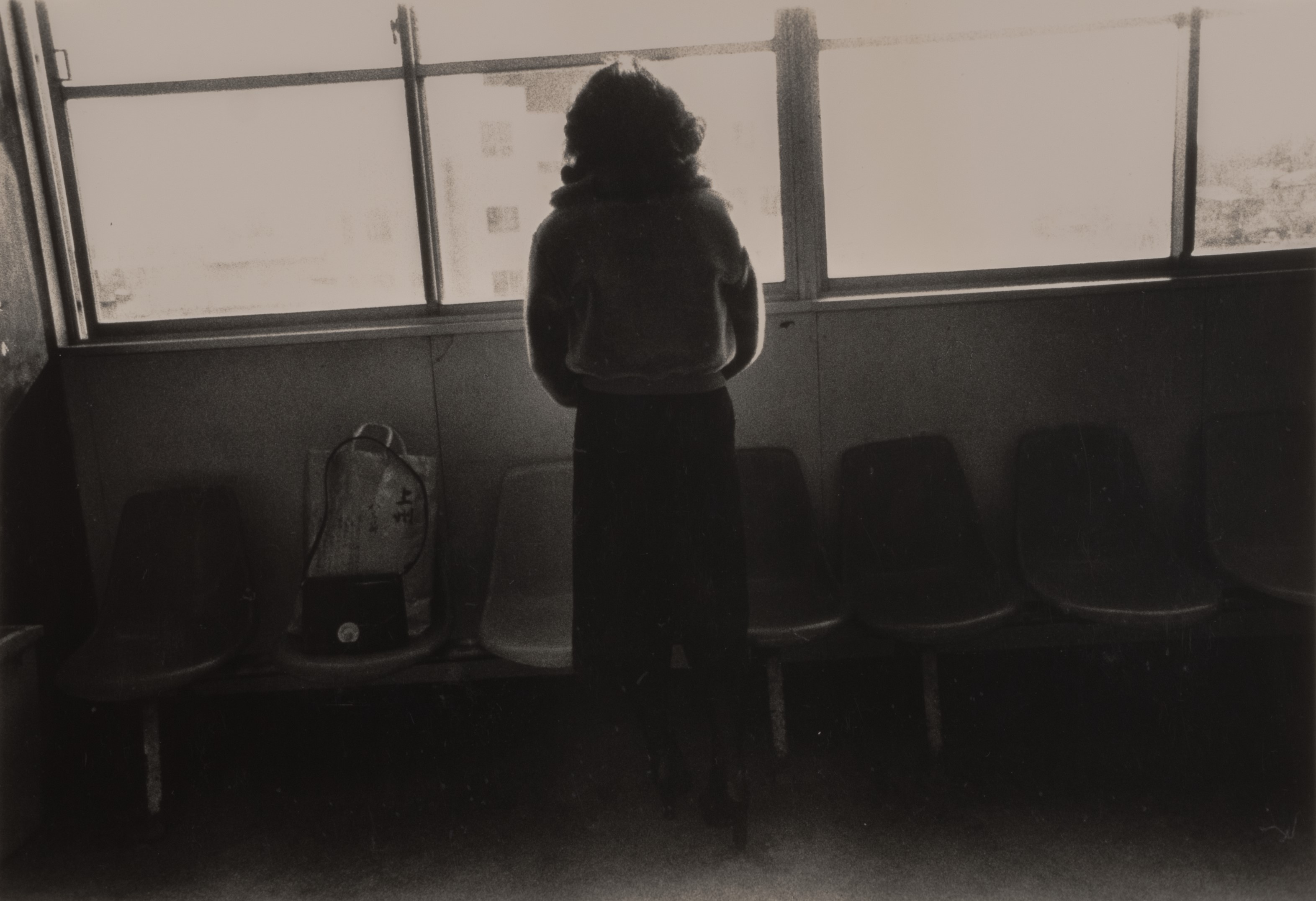

Tamiko Nishimura — I wonder if younger generations are interested in this type of photography.

Hiroko Maruyama — To be honest, on the opening reception day, I visited the Alison Bradley Projects gallery without knowing whose exhibition was being held there. As I looked at the artworks displayed in the gallery, I thought, "These photos resemble those from Japan's Provoke era." However, the more I looked, the more I felt that there was something completely different about them.

Upon reading the exhibition description, I learned that the artist is a Japanese photographer who graduated from the Tokyo College of Photography [now Tokyo Visual Arts] in 1969 and has been active ever since. The fact that these photos were taken from a female perspective, which was not often seen in the photography of that era, piqued my interest greatly. Fortunately, I had the chance to meet you in person at your exhibition, and I feel very honored to have had this opportunity.

In the 1990s, movements of female photographers emerged in Japan, but in the 1970s, it was an era when photography was openly regarded as the least suitable profession for women.

The Girly Photography movement emerged in Japan in the 1990s partly because lightweight and compact cameras were introduced during that era.

Right. This camera [Nikon F3 single-lens reflex 35 mm camera] weighs over a kilogram.

How did that first camera come into your life?

Growing up, my father was into photography as a hobby. Our house had an environment where several cameras were lined up on top of the dresser. He had motion film cameras like 8 mm and 9.5 mm back then. I still have footage he shot with those formats. With cameras always around, taking photos didn't feel like a big deal to me.

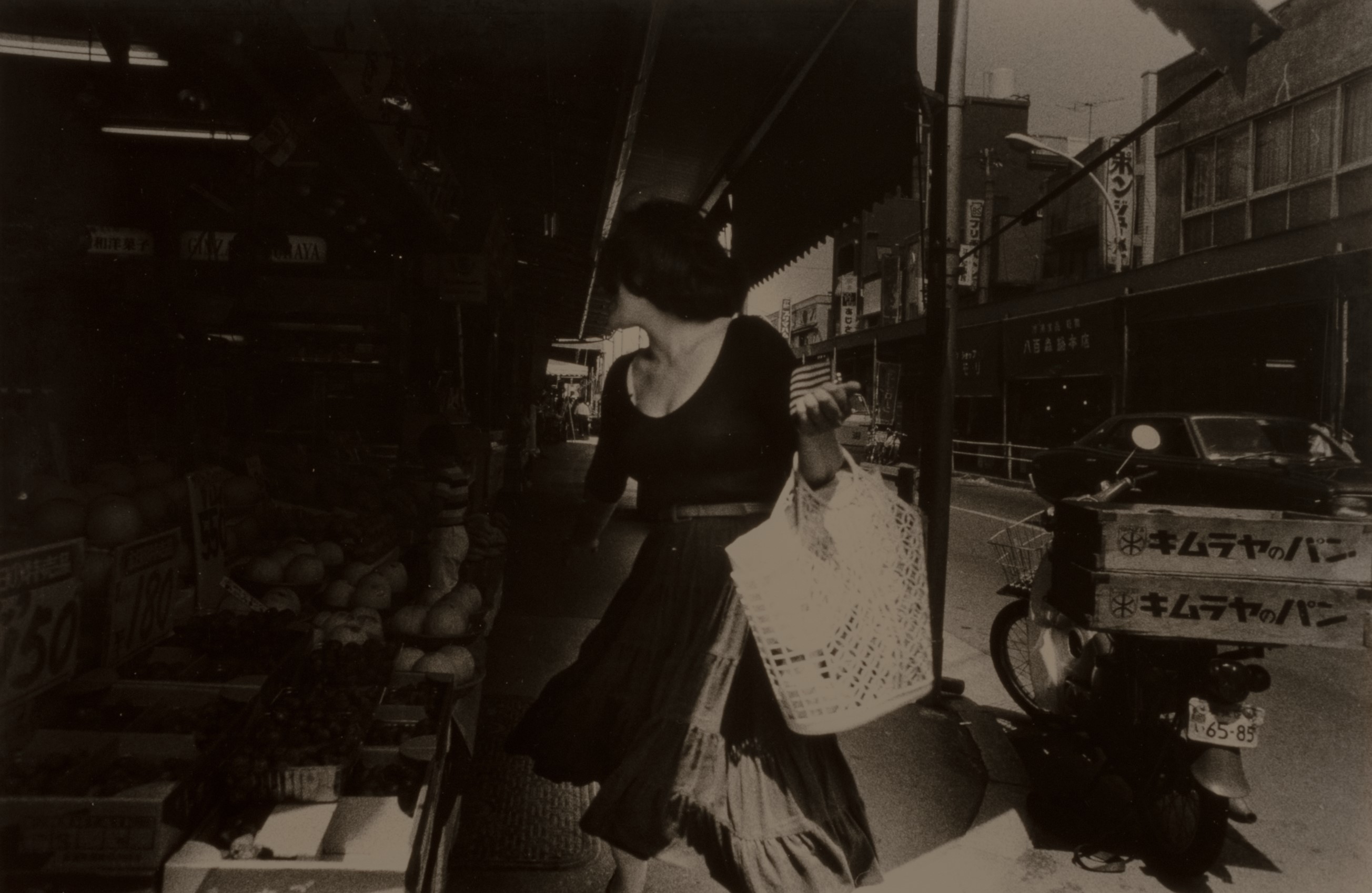

What kind of moments do you usually capture with your camera?

It's about encounters, you know, between the subject and yourself.

All the experiences you’ve had since you were born, including the ones you have forgotten. It is through these experiences that you’ve become who you are. Like when that version of yourself meets the world, you know? When you see someone's profile and find a nice angle or something. When the light hits them just right, without even thinking — you feel it and capture it. Those encounters are shaped by what you have cultivated, and you shoot with your own intention.

Your works often feature photos taken during your travels. Do you find more encounters as you travel around?

When you're traveling, you completely forget about any ties or obligations, right? Because you're only focused on exploring a new world — I think I enjoy that sensation. I frequently set off on journeys, work part-time to save money, then travel again, take photos, print them, bring them to the editorial offices of photography magazines, get them published, and then use the fees I receive to travel once more. It's a cycle.

In this exhibition, I'm also displaying magazines from that time that featured my work. About 90% of my photography trips are solo endeavors. Photography is something I do intensely on my own.

Smart. I respect you for how you've already set up this whole organic cycle within society, even though you started on your own.

Thank you. But back then, I was just a girl, you know? I nervously cold-called the magazine Camera Mainichi, saying, "I'd like you to see my photos." Then they said, "Come in such and such day at such and such time." I brought my prints, and the editor-in-chief flipped through them like shuffling cards. They would say, "We'll keep your work," and then I would hear back from them when my work was decided to publish. I continued in this manner.

Editors like Syoji Yamagishi, the editor-in-chief of Camera Mainichi, and Mr.Kōno, who was the editor-in-chief of Nippon Camera, were instrumental in understanding my photography. Their conformations affirmed my sensibility of capturing my idea of "encounters."

I think their support was crucial. Mr. Yamagishi was one of the top editors in Japan and was known for discovering photographers like Daido Moriyama and Kishin Shinoyama.

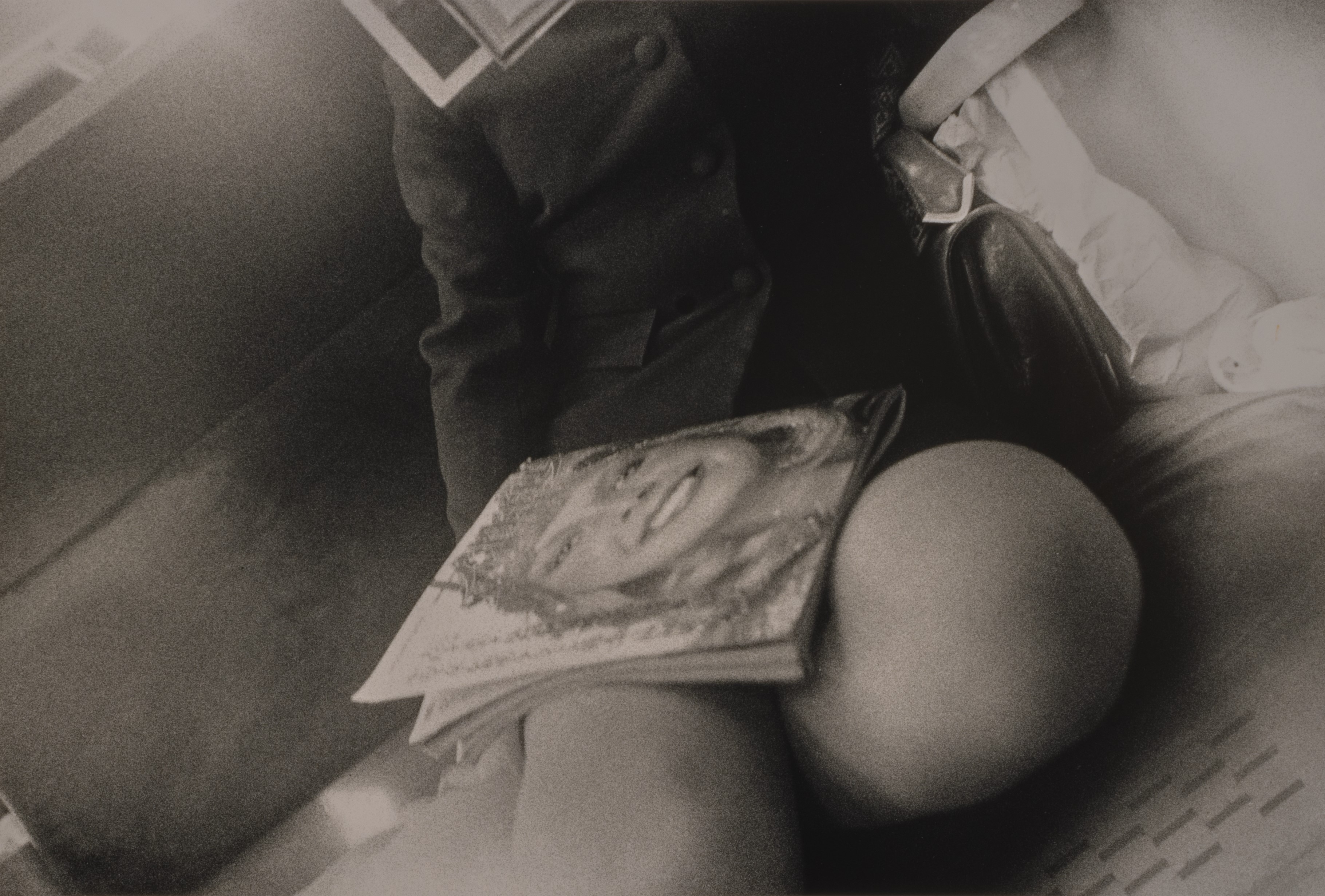

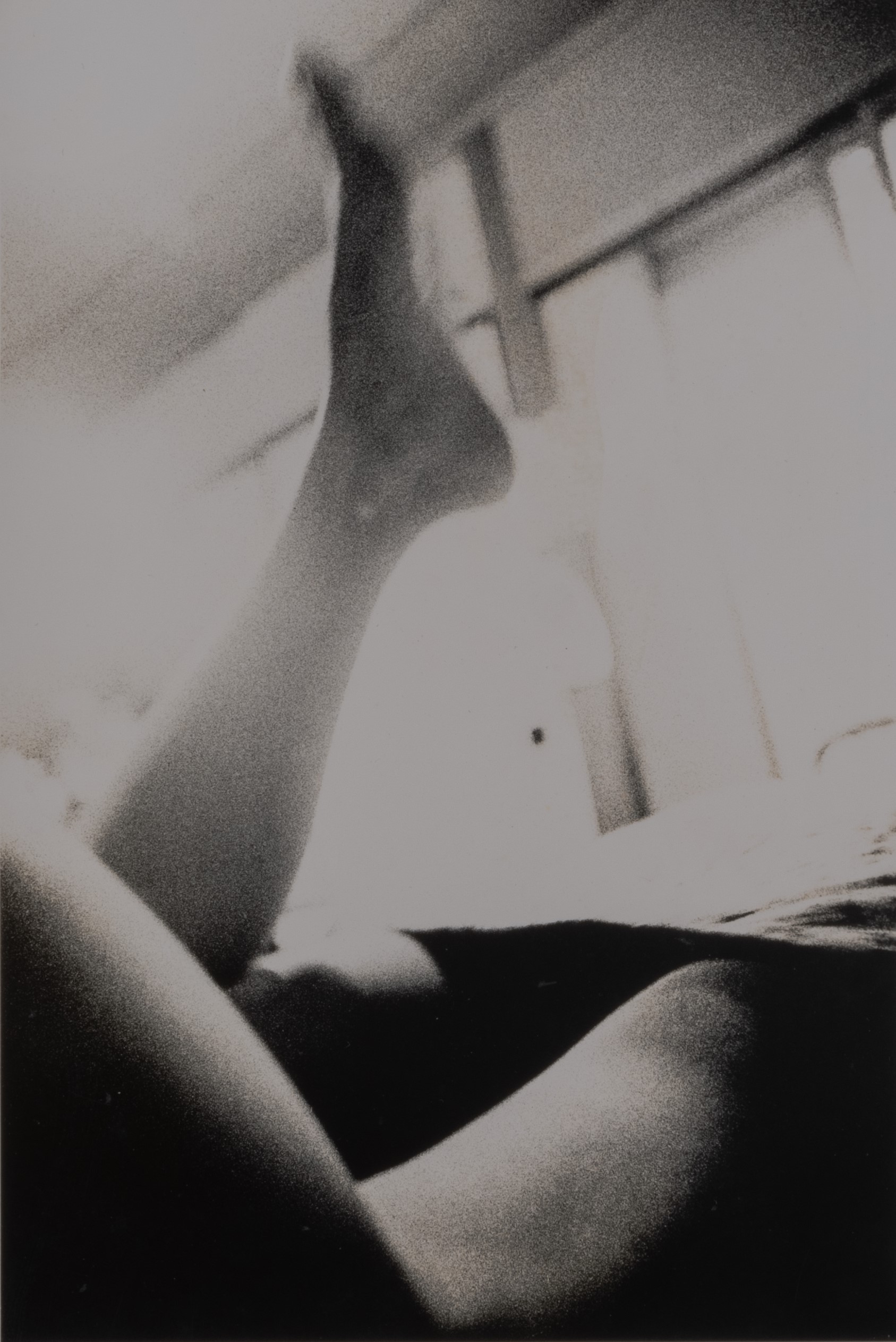

Kittenish... (2015)

I saw the artwork series Neko ga ... (Kittenish ... ), which was first unveiled on the pages of Nippon Camera Magazine in 1970. I found the photographs to have a rough texture and realized the image depicted women photographed at close range.

What struck me was the perspective, which was completely different from what is known as the so-called Shi-Syashin movement of the 1970s in Japan.

When I thought about why, I realized that I didn't sense a male gaze in this photograph. As the title suggests, the image felt like it had the perspective of a cat, in a room looking at the subject, with the shutter clicking every time the cat blinked. Your exhibition was a pleasant encounter, and I am glad that my preconceived notions of Shi-syashin-era photographers that I had before seeing your work have been removed.

Have you heard of the 35mm half-size camera? It's called the Olympus Pen Half Frame. You can take about 70 shots with 35 mm film. That's why the texture looks even rougher.

The editor-in-chief of Camera Mainichi, Mr. Shoji Yamagishi called me and said they were going to feature four or five female photographers. They needed some photos. I thought about bringing some travel photos, but then I thought it might not be that interesting. Since a friend happened to be visiting me, I spent two or three hours snapping away and brought those instead.

The editor-in-chief saw my series Neko ga ... (Kittenish ... ), and his first words were, "Tamiko Nishimura has brought back some naughty photos."

Since I had been showing mainly travel photos, I don't think he expected me to come back with such a series.

Haha. I like the series.

Thank you. Since I was short on time until the deadline, I shot the photos, developed and printed them in the darkroom immediately, and then took them to the editorial office.

I use Kodak Tri-X film, and I still develop the film myself in the darkroom. While I sometimes shoot with color film, I've been using Tri-X film for fifty years when shooting in black and white.

Why do you prefer using Tri-X film?

I like this film because it has a strong contrast between black and white.

I see. I've heard that you use high-temperature development and long-exposure techniques to enhance the contrast in your images. This film is an indispensable element in your artistic expression, isn't it? What's the story behind this exhibition? How did it come about?

Alison, the gallerist at Alison Bradley Projects gallery, reached out to me after seeing my first photo book, Shikishima.

I was 23 when I published my first book, and I didn't have much knowledge about promoting my work, so there wasn't much response at the time. It's only after some time has passed that I feel Shikishima has been appreciated.

My Journey (Ryojin) (2018)

My Journey II. (1968 - 1989) (2020), My Journey III (1993 - 2022) (2022)

You worked part-time for a short period with Kōji Taki during the early stages of your career, between 1969 and 1970, and regularly assisted in the darkroom shared by influential Provoke members Daido Moriyama and Takuma Nakahira. While your involvement is sometimes discussed in the context of the Provoke movement, I strongly sense the pursuit of your projects through your works and in our interview at this time.

I've simply continued taking photographs on my own for a long time without getting involved in the photography industry per se. Egotism, or similar traits, are endless, and when they creep in, they manifest even in photography. I've avoided all that because I don't want to feel any of it, so I've been doing it on my own. It's still the same today. As I see it, humans are creatures that don't change easily.

Many visitors attended your exhibition’s opening reception. How was the audience for you in New York? Did you have direct conversations with them, and were there any words or reactions that left an impression?

When asked about my worldview, I found myself thinking, "worldview, huh?"

It was quite intriguing to be exposed to various perspectives, and I enjoyed seeing everyone's reactions. I couldn't help but feel that maybe in America if you don't explain things in words, they won't get across. That aspect felt very appealing to me. I've wanted to go to New York since the 1970s, but over time, it became a place that seemed less accessible, as my desire grew stronger. I feel truly fortunate and moved to have the opportunity to share my work with everyone in New York, thanks to meeting Alison and the connections made. Yesterday, I saw the city of New York from the Empire State Building.

I know, I heard from your friend Kazuhiro Yamaji of Flying Books [bookstore in Tokyo] about that this morning. I asked him if the rooftop of the Empire State Building gives the impression of strong winds. Kazuhiro said, “She was taking photos and calmly changing films on the windy rooftop.”

You took a lot of pictures on this trip, and I'd be happy to have the opportunity to see them soon.

I'm planning to develop them as soon as I get back [home in Japan].

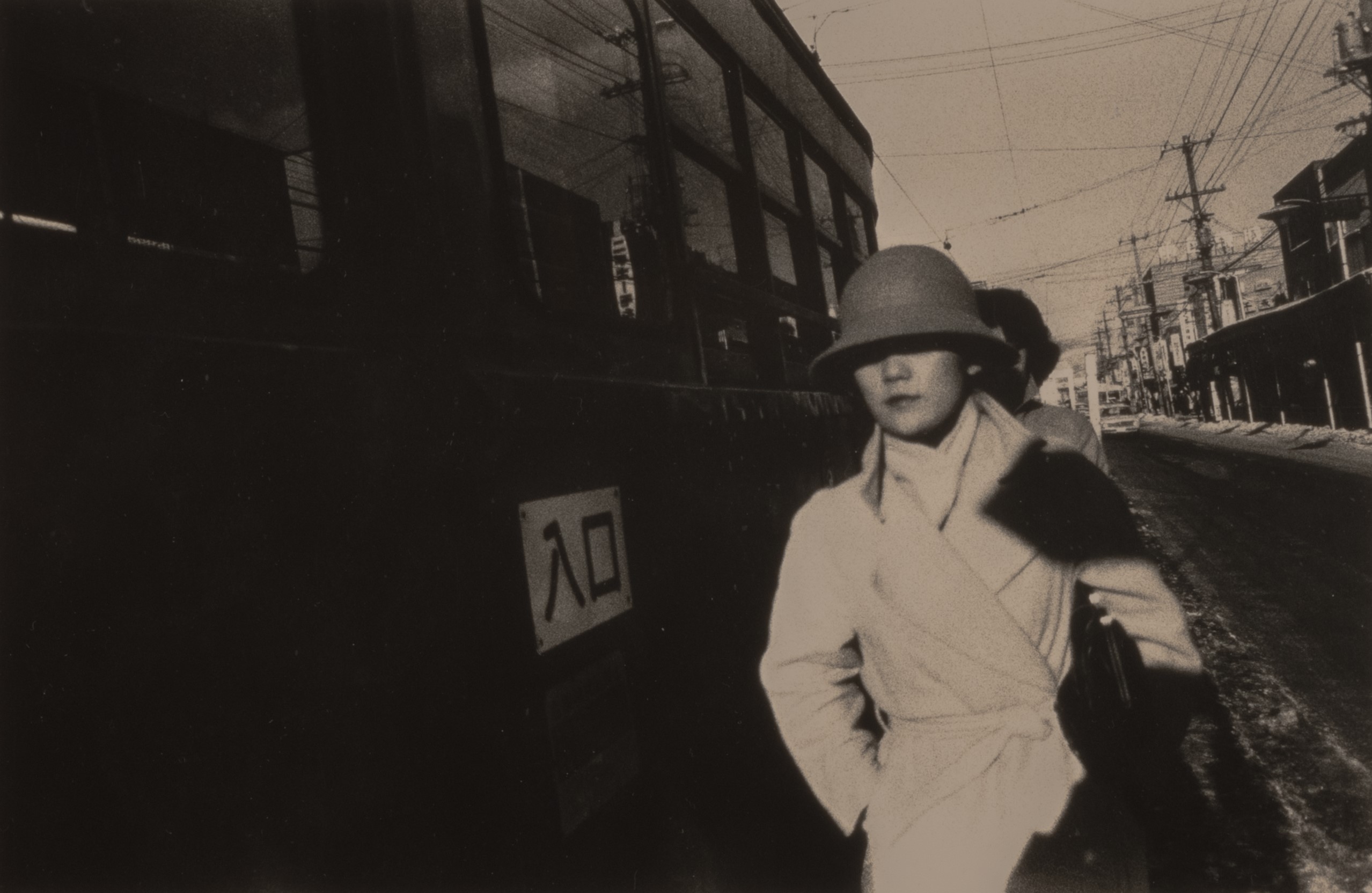

Could I ask what you always bring with you when you travel, as a final question?

I'm from Tokyo, but when I was around 20 years old, I loved traveling to the northern regions like Aomori and Hokkaido. I always brought a paperback of Dazai Osamu's Tsugaru with me. At that time, I used to travel by overnight train, departing from Ueno Station at night and arriving in Aomori by morning.

There are songs in Japan with lyrics like that, right?

Yes, you're right. The songs were written long after my travels, but it felt like that back then. I remember reading that book on the sleeper train to Aomori. After finishing it, I'd leave the paperback at the ryokan wherever I went. But I always wanted to bring the same book on the next trip, so I ended up buying five or six copies of Tsugaru in paperback.

What did you like about Dazai Osamu's Tsugaru?

Dazai Osamu was an author who passed away the year I was born, but in Tsugaru, I felt he depicted the Aomori I knew. For instance, about Cape Tappi, there's a line in Tsugaru that goes, "I thought I was sticking my head into a chicken coop, but it turned out to be Cape Tappi."

When I first visited Cape Tappi, I had exactly that sensation of sticking my head into a chicken coop. There were still such familiar sensations there. Japan changed a lot in the 1970s and 1980s, becoming modernized. Before the 1970s, throughout Japan, there was still a connection [culturally] to the eras of Edo, Meiji, Taisho, and Showa.

Everything started changing in Japan, and wherever you went, you'd see the same landscapes and sceneries once you got off the train station. This prompted me to start traveling abroad.

I lived in Mitaka, Tokyo, for eight years. I commuted daily from the station to my home via Tamagawa Josui. Dazai Osamu also lived in Mitaka, didn't he? There was a Dazai Osamu study group in Mitaka, and I participated in the group as well.

When you look at someone's bookshelf, you can somehow understand their personality, I think. And hearing this story made me feel like I got to know you a little better. Did you release a new book in 2022?

Yes, I have been taking photographs for about 50 years, and I have compiled them into a work of art [My Journey III. 1993-2022, published by Zen Foto Gallery, 2022.] I have many unpublished photographs, most of which were taken in the 1970s, and I plan to publish them this year.

Journeys is on view at Alison Bradley Projects, 526 W 26th St #814, New York, NY 10001, through June 29, 2024.