Stored

The series produces an eerie prediction for what's to come. "A day in summer 2020. Social isolation has become normal. The new disease is called hypochondria," says Roché.

Check out the rest of the series below.

Stay informed on our latest news!

The series produces an eerie prediction for what's to come. "A day in summer 2020. Social isolation has become normal. The new disease is called hypochondria," says Roché.

Check out the rest of the series below.

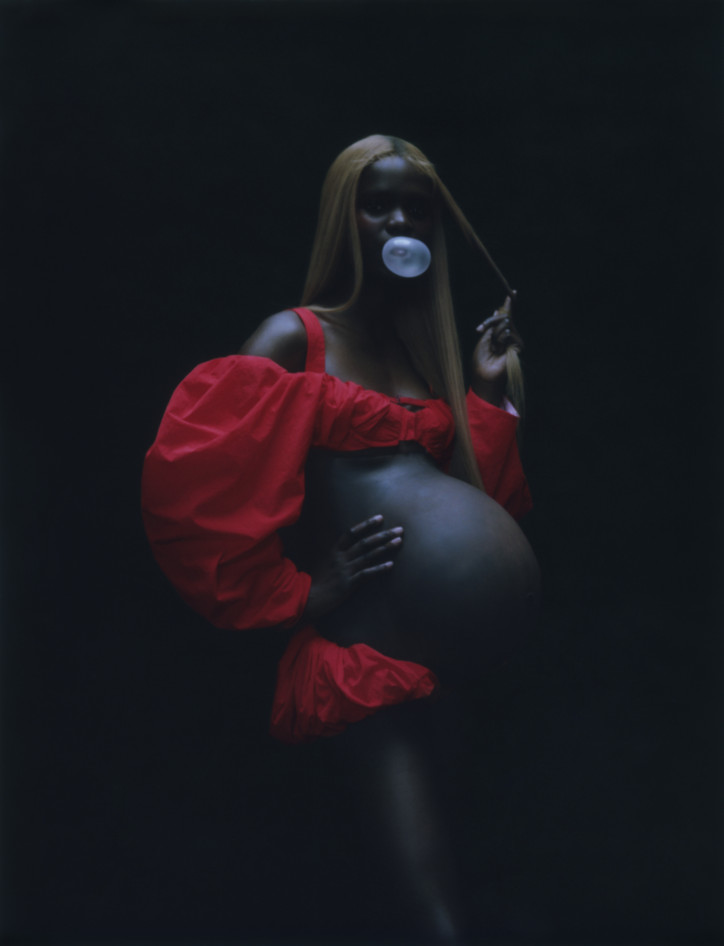

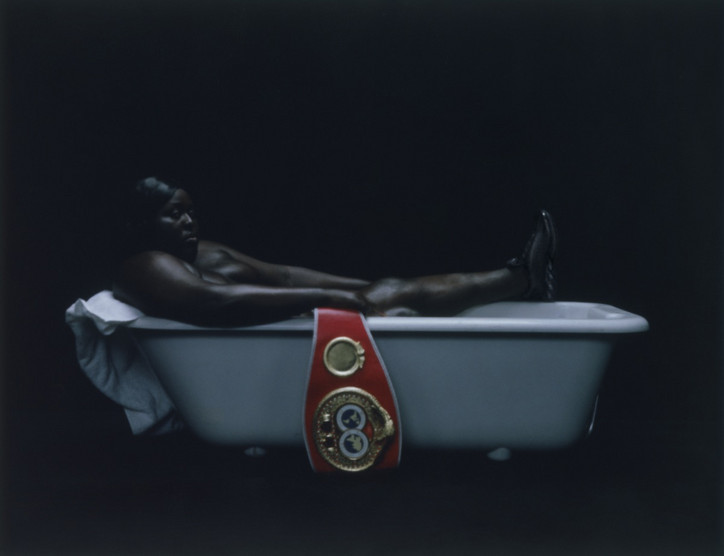

Throughout the room, each photograph unfolds a captivating story. Entranced, I find myself envisioning the vitality captured within the frames — young ballerinas’ graceful movements unfold in slow motion as they kneel down, foreheads to knees, hands rising and falling in a choreographed display. The spell is broken by distant chatter, as the room fills with animated voices and flashes that reveal my reflection in the next piece on the wall. Now observing a pregnant woman, her belly so prominent that when I focus in I see myself in it, as I contemplate the heightened appreciation for the female form. The artist's male gaze, devoid of hypersexual poses, conveys power and beauty in a unique and much-needed way.

Moses discloses that the pregnant belly in one of his works was, in fact, a prosthetic, skillfully portrayed by the model. Normally, most photographers stay away from featuring anything other than a flat stomach. For an artist to recognize the beauty of a full stomach — so much so that he actively search one out — further solidifies Gabriel Moses as a once-in-a-lifetime talent.

The exhibit, serving as a tribute to the femininity that has shaped the artist, now sparks curiosity about the evolution of his perspective and exploration of the parallels between Regina and Marsha. Reflecting on his upbringing, Moses shares, "Being raised in London, in a single-mother household with my sister, I gained immense respect for their perception of beauty. My home was a sanctuary without toxic masculinity, allowing me to see life through their lens in hues of pink. When I held that camera, I knew what I wanted to create. Naming my projects after the inspirational women in my life — Regina, the name of my studio, which in translation from Latin also means Queen, and Marsha, my hairdresser — was my tribute to their impact on my journey."

Evaluating his multifaceted career through fashion, sports, and film, we speak about the importance of diversity in the artist’s creative vision. "I create moments inspired by the past and the future,” Moses explains. “My grandmother left me with royal memories that I've fallen in love with. She was a dynamic woman, as was the generation before me. I’m going to have daughters and nieces. I have to create an environment — especially now as an artist — to ensure they see representation and produce art that allows them to grow up loving themselves. This responsibility stems from the love my mother poured into me, even creating for people I don't know. That's the beauty I see, and I won't portray anything else." Such a heartfelt reflection reveals Moses’ deep appreciation for his roots, highlighting the influence of personal experiences and family ties on his outlook. The confidence instinctively built into himself is seamlessly depicted in his works. It makes sense.

Back at the reception, Moses holds flowers and momentarily stands out; otherwise, he's blending into the crowd. His emphasis on world-building is evident as he discusses the independence he maintains in his work. Perhaps, Moses exemplifies a lesson: maybe you're not meant to do everyone’s work if there are conditions to your process. "There are no rules. I do what I want because I don't chase what's not for me. If I can't do it my way, I'll do it on my own."

Shifting the focus to his filmmaking process, we discuss the emotions he aims to evoke in his audience, noting the quiet backdrop in IJÓ and Regina, in contrast to the liberation and airy emotions in Marsha. "I'm all about feeling. I'm not the biggest on films." Moses claims. "Psychology, details, colors, tone, and movement — these elements come together naturally for me. Connecting from an audience level, I create films that resonate with how I would feel. Quite airy, beautiful, subtle…"

The discussion extends to his upcoming book, set for European drop in the first week of April, and US drop in early June. Moses reflects on the significance of physical representation in a world dominated by social media. "It's about timelessness,” he starts. “Growing up in a social media world, I still need to produce things that can be passed down. The physicality of a book offers a different experience, and I want kids to discover my work in libraries – an experience unlike seeing it on a phone. This book also comes with personal archives; images from my childhood, my family, my friends… It’s a well rounded look into the word that is around me and one that I am creating through me. "

Reflecting on his unexpected foray into fashion photography, Moses shares his perspective “Did you ever think this guy would be a fashion photographer?” “Growing up in London was a moment to express oneself. But I don't get too excited; I understand the ebb and flow of good and bad moments. They are purely fleeting moments.” Chicago, in Moses's eyes, becomes a testament to the reach of his work, exceeding expectations with its warm reception. "I had no expectations, and it's humbling to see people leave their homes to experience my work in a city my mom and I have never been to. It's a testament to how my work has traveled, and being here feels like home."

Concluding the interview, I take a personal moment with Marsha, immersing myself in the African cowboy narrative. Moses, through his masterful use of colors and imagery, challenges false narratives and showcases the rich history of African American cowboys. His distinct style, despite his youth, prompts contemplation on the control he exerts over his conditions and artistic vision.In closing, Moses emphasizes his pride in his work, inviting others to appreciate it as well. He leaves us with a parting lesson: perhaps not every task needs to align with one’s creative process. He asks us a question that gets to the heart not only of his practice, but of his philosophy: “Do you love your work, or do you just love the way you’re being received?”

How should we listen to Score, for Ellipsis & Roundtable if at all?

I’m not sure if there is a proper way to listen to Score; it’s just a meek ambient sound that is meant to re-enact that white noise of when you’re waiting for things. In this work, the constant dialogue that is hallmark to AM radio starts to become more like an opaque wall of chatter, which makes this aversion to dead air super palpable. That adage of not being able to "get a word in edgewise" is central here. I have always been interested in seemingly impenetrable borders, especially when it comes to cultural exchange. In this case, I wanted to play with the one thing that AM radio seems to be allergic to, which is music, but a flimsy, hyper-analog version of it.

Score, for Ellipsis & Roundtable, 2024

Zip-Liiiiiine, 2024

Zip-Liiiiiine is cute! Do gallery-goers step over him?

For the most part, no. However, I do like that the authoritative function of stanchion is now endowed to this silly little sloth performing as an art object. I wanted to double down on the pliability of the stanchions with something that was dubiously heavy, à la a sloth plushie filled with gravel. Like giving the thing different terms it never possessed — let’s call it slothiness in the expanded field, haha. I also think the titular gesture of elongating the word “line” really stupidly captures these conditions of ambivalence and anachronism that are central here.

Tell me more about the giant wallpaper depicting the Statue of Liberty! What was the process of searching for the perfect Statue of Liberty picture on Getty Images like?

That specific wall in the gallery always felt like an image of itself and I wanted to revert it back to just being a wall, using a free image of freedom and stanchions. So we prioritize the dimensions of the wall with this poor image, with no real concern for its fidelity. Shoutout to Louise Lawler! As per the actual selection of images, I really wanted that specific shade of navy sky where it’s unclear whether it’s the beginning or end of the day. Let’s call it Schrödinger’s atmosphere: within this image, liberty toggles between AM and PM much in the vein of how bureaucracy maintains its 24/7 operations.

Grey's Foreclosure, 2024

The foreclosures are quite uncanny. What was your inspiration for them?

The foreclosures reference boarded up windows, which I’ve always enjoyed in that they tend to reassert the scale of cover-up — when you see a boarded up house and you’re reminded how big brownstones really can get — and elicit speculation, the type where the worst-case scenario is the first thought. They’re these sexy NPC placeholder-objects that have a very seductive type of opacity, the type of surface most akin to those animatronic sculptures you would see in Chuck E. Cheese. I’ve always understood plasticity as a good surrogate for performativity, or lack thereof.

Which content house spooked you more? New York or Los Angeles?

I think I am equally ambivalent towards both places, though I will say I have some level of Stockholm syndrome with New York. I feel most myself when I’m here, but feeling like yourself all the time is so exhausting. But all that California sunshine and manifest-destiny flavor of square footage can really melt your brain. This is probably a fitting framework to think through the content house as a site of cultural overproduction and the different types of excess that that has generated. In my head, the NY-excess reads more like an image that constantly preemptively documents itself; the LA-excess feels like some bad volumetrics, like those stilted megahomes that are built on mountainsides–just something I’m still thinking through.

What is the relationship between the big mascot and the small mascots? Are they a family? And why sperms?

Formally, they’re laid out in a way that prompts a left-to-right orientation. It’s this mother-duck-ducklings kind of queueing. On the other hand though, the little sperms being 3D-printed and serialized speaks to manufacture and prototyping. One may read this queue of sperms as “attempts” towards the big sperm. A trail mix of nuts that either shoot out from or lead to the big nut! The sperm is this naughty proxy for artistic production and reproduction. The punch line here is the male, genius trope. I wanted to smother it with this inbred assembly line of cultural archetypes.

I like invoking family because it sets up reproduction (I love you so we must build a life together) in tandem with preservation (I love us so we must continue our namesake). It’s also something that everyone is complicit in, with and without their consent, for better and for worse. This is a fitting model for artistic production/cultural participation.

Both Smokin' Tiki and Chair with Pipe feel intimate and absurd. How do you balance the two affects in your works?

Not to do some cheap poetry here, but I think to engage in any level of intimacy requires some faith in the absurd. It feels odd to involve oneself in any type of attachment, regardless of how often or how much you might want to. So maybe it’s more apt to call it flailing between the two, in a concerted effort to safely experience precarity. The world loves to impede on and snuff out our desire for change, so you kind of have to gamify your position and aspirations in order to counter that.

Chair with Pipe, 2024

Big Mascot (Ragamuffin), 2024

I love the honesty of Incubator! Sincerity in self-criticism is rare these days. How do you keep up?

The usual image of “keeping up” sounds a bit impressive and affirmative for my liking–I have way more faith in my own pettiness. And I say pettiness to foreground this antagonism inscribed within Incubator. It’s the gallery’s storage room, and you can’t spell “storage” without “stage.” The monolithic lamp inside flickers arbitrarily like a thunderstorm, which is bolstered by this 2-way mirror that is surfaced with false raindrops when you look through. Imagine there was a weather machine in the Kapp Kapp storage? It all works to dramatize inventory, the tragicomedy of “stuff”.

I was thinking of storage as the art object’s equivalent of a commons: intensive care unit meets daycare facility meets town hall meets morgue. Yet the storage room remains hidden. So it felt proper to stage some of my past work in this voyeuristic game, which maybe one could call “sincerity.” Again, I return to pettiness.